Israel

In Israel, the connections between straight edge hardcore and political activism have been strong since a radical hardcore underground with anarchist leanings emerged in the 1990s. Jonathan Pollack has been part of the scene almost from its beginnings. In 2003, he co-founded Anarchists Against the Wall, an Israeli direct action group that supports Palestinian resistance to the Israeli occupation. Jonathan lives in Jaffa.

The hardcore scene in Israel is tiny, and in the mid and late 90s there was indeed a very strong link to anarchist activism and politics, mainly due to bands like Nekhei Naatza and Dir Yassin. The atmosphere at shows was political in a very deep and in-your-face way, not something you could escape or consider as nothing more than cultural white noise.

Straight edge was part of that scene, even a prominent part at points in time, but never detached or separate. The fact that both of the aforementioned bands had Straight Edge members in them—while neither was a Straight Edge band as such—is a good example for that.

In a country that isn’t much more than a huge military camp, it was clear how and why punk and politics mix, and for those of us with Xs on their hands, growing up in that scene, Straight Edge was politics years before I saw it on a Catalyst t-shirt.

A lot of what and who I am today is greatly indebted to that scene and its amazing people and spirit. While remnants of that attitude still endure today, I feel the scene—in general, and as far as Straight Edge goes—is much less overtly political today than it was then.

No, there just isn’t really a separate Straight Edge scene in Israel. It used to be very rare to come across Straight Edgers who weren’t, at least superficially, political. However, with today’s general decrease in the emphasis that the Israeli hardcore scene puts on politics, you can now also encounter non-political Straight Edgers.

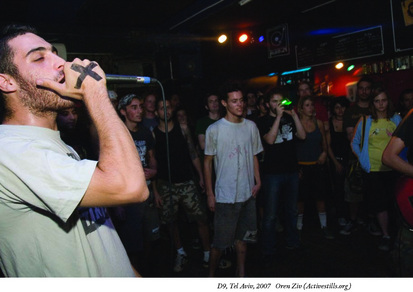

Thinking about it though, for many of the “old timers” losing interest in Straight Edge seemed to be a precursor for losing interest in politics as well. (Image 8.1)

Image 8.1

While I do see Straight Edge, in its essence, as a political choice, it doesn’t interest me as a political movement or as a scene separate from the hardcore scene.

For me, Straight Edge is, and always was, a gut instinct. I remember being drawn to it as a teenager, long before I had the tools to dress my choice in the fancy robes of radical discourse and complex politics.

I was initially attracted to Straight Edge by the need to depart and distance myself—mentally, emotionally and politically—from the culture of my contemporaries; a culture obsessed with money and commoditization of leisure and personal interaction rather than with freedom; a culture in which the most upsetting thing you could do was to reject manufactured leisure.

Today, through the filter of years of activism, and with the ability to put Straight Edge in political terms, I am still not interested in doing so. It remains in the realm of clutched fists, red rimmed eyes and a raging gnash at the world around me, an instinct. Put again in the simple terms of a teenager, Straight Edge is the ultimate Fuck You.

In a realpolitik context, the links between drug abuse or alcoholism and poverty, or between cigarettes and transnational corporations, are just another—and not even a very central—aspect of a fucked up world; another item in the endless list of boycott-worthy items if you’d like.

Straight edge’s political importance lies in its explosive cultural charge. This is the real challenge that it presents, and why it connects so well with punk and hardcore. Unlike with more concrete political issues, there is no point in convincing people of Straight Edge’s merits—being mostly instinctive, it is a fire that either burns within you, or it doesn’t.

As a political idea, the Straight Edge of ebullient refusal to the decadence of our times is not that of an ascetic anchorite in the badlands of western civilization or of religious purity. The need to extract oneself from society, so prevalent in Straight Edge, is fuelled by the desire to see and live a different reality; a desire that can’t subsist in the clubs, cafés and drug culture of mainstream society. Both my Straight Edge and my activism are strongly rooted in this passion, and neither is dependent on whether we will reach this different reality or not.

Activism sends one through the hollows and dells of failure and despair, and with all the positivism in the world, I doubt anyone seriously invested in a meaningful struggle can truly avoid these feelings at times. In my personal passage through the lands of political involvement, and especially through its lows, I’ve seen people shot dead for nothing more than demonstrating or breaking a curfew. Unfortunately, more than once, this happened meters away, right in front of me, and I couldn’t do anything about it.

These are experiences that sink deep into one’s soul. They occupy my nights and my sleep just as much as they occupy my days and waking thoughts. But still, despite its toll, I feel very fortunate to be part of such an intense struggle and to be satiated with its radiant passions, as well as its true sorrows.

For me, it is this choice, of real passions over the ready-made passions produced by the market, of true liberty over numbness and indifference, where Straight Edge and activism connect.

I’d say it’s closer to the latter. As I’ve explained before, while I don’t ignore the ties between, say, alcoholism, poverty, and transnational corporations, I doubt they could justify the centrality Straight Edgers assign to alcohol consumption in our identity.

Whether a beer was produced by exploited laborers or a DIY microbrewery, is a question that should interest drinkers, not Straight Edgers. The real issue I recognize concerns not the on-the-ground economic circumstances of these products—these can indeed be circumvented—but rather the place that these substances hold within our culture, and what it means to reject them.

I tend to think that Straight Edge is a rejection of cultural consumerism in a way that goes beyond the mere ritual of monetary transaction. In my experience, alcohol, drugs and cigarettes have an important significance in the mainstream culture of hedonist indifference, in the acquisition of “cool,” in the promotion of ready-made sterile rebellion-for-the-masses.

There is often a somewhat condescending tendency within radical circles, where we assume that once we’ve understood the context of things, we are in a way immune to them, as if we are in some way purer than the Average Joe. I think you can’t expropriate drinking, smoking and drug use from the long dark night of trade, and it doesn’t really matter if it’s home-brewed or not. You just can’t beat the system from within. For some reason, this is a commonly held view among anarchists with respect to, say, electoral politics, but not so much when it comes to cultural issues—where I think it’s even more applicable.

As I said before, Straight Edge doesn’t really interest me as a movement. Over the years I’ve met some very interesting people and it is with them I keep in touch, not with their scenes.

However, even though the mainstream of Straight Edge, with its puritanism and macho attitude, isn’t very interesting, the radical margins are full of beautiful, passionate and original people and ideas. Generally, as a rule, the farther you get from clean-cut looks and fancy clothes the more interesting Straight Edge will probably get.

Yeah, I guess it probably is...

Anyway, despite the way I feel about jock culture in Straight Edge, veganism and animal rights’ prominence in Straight Edge is not something to be ignored or taken lightly. While I don’t really connect with a lot of things around bands like Earth Crisis, I treasure their contribution to transforming animal rights and radical environmentalism into a central issue for Straight Edgers.

Well, I’ll try doing that without going into the depths of the complex and long history of Zionist colonialism in the Middle East. This history started at the very end of the 19th century, when a Jewish national movement began winning the hearts and minds of European Jews, with the aim of colonizing Palestine, which at the time was under Ottoman rule. Today—after establishing the “Jewish and democratic” State of Israel in 1948; after wars that have caused hundreds of thousands of Palestinian refugees, and after long periods of military rule—Palestinians remain either second class citizens in Israel, or subjects without rights in the Occupied Territories of Gaza and the West Bank.

The first outbreak of widespread popular resistance in the Palestinian Occupied Territories was sparked in December 1987 and became known as the Intifada—“uprising” in Arabic. It subsided with the signing of a so-called peace accord in Oslo in 1993. When the hopes and promises of the peace process were not met, a second Intifada erupted in October 2000.

Today, we are witnessing the perfection of a very sophisticated regime of racial separation ( Hafrada in Hebrew, Apartheid in Afrikaans) in the Occupied Territories—a regime that’s extremely brutal on the one hand, and, in many aspects, almost completely invisible on the other. Israel’s acts are driven mostly by the desire to retain and strengthen its control over the land and the civilian population. Even the military withdrawal from the Gaza Strip was motivated by this: Israel practically retains control over the Strip and keeps it besieged, but is now provided with more international legitimacy.

One of the landmarks of the Israeli project of separation is the construction of the West Bank barrier (“The Wall”), which Israel started building in 2002, and which will practically annex about 10 percent of the West Bank to Israel when complete. The wall, together with the Jewish-only road system, Jewish-only settlements, prohibited zones, checkpoints and roadblocks, will secure the division of the West Bank into islands of territorial discontinuity, and ensure Israeli control over the scarce water resources.

The construction of the wall, with its grave implications on Palestinians, was also a catalyst for a new wave of popular struggle that started soon after construction had began, peaked in 2004, and continues to date.

The struggle against the wall, throughout the West Bank, mostly consists of almost daily demonstrations, riots and direct actions. People gather and march towards their lands where Israeli bulldozers are working, with the aim of disrupting and sabotaging construction. Demonstrators are usually met by military repression that varies from teargas and concussion grenades to rubber-coated steel bullets (very different from rubber bullets in most other places, often lethal) to, at times, the use of live ammunition.

In the past six years nineteen people, ten of them minors, all of them Palestinians, were killed in these demonstrations, in which firearms were only ever used by the army, never by protesters. Thousands of us, Palestinians, Israelis and internationals have been injured, many seriously. Hundreds have been thrown in jails, prosecuted and imprisoned. The Israeli army, like any army faced with a civilian uprising, knows no other way to deal with civilian dissent but to try and stifle it with extreme violence.

Anarchists Against the Wall is really just a side note in all this—Israelis joining an essentially Palestinian movement. I guess you could say that small bands of vagabond and treacherous Israeli anarchists roamed through the Occupied Territories from the early days of the second Intifada, drawn to the popular insurrectionary resistance to the occupation. These people later grew to become Anarchists Against the Wall, which is a more organized attempt of Israelis to join the resistance of Palestinians, as well as a means to enable others to do so.

As anarchists, many of us were obviously attracted to participate in an insurrectionary situation taking place right at our doorstep, but the rationale of joining Palestinians who put up resistance goes beyond that. The fact that we oppose the occupation, Zionism in general, and even the existence of nation-states per se, does not relieve us of our responsibility for what is done by our governments on the ground. Israelis, anarchists too, are the beneficiaries of Israeli apartheid, and it is being carried out in our name. Israeli apartheid and Israeli occupation will not end by itself—it will end when it becomes ungovernable and unmanageable. Being part of the effort to reach this situation is our moral duty. We can’t cast aside the national identity with its privileges and moral obligations that has been imposed on us. Especially here, we are Israelis whether we like it or not.

Aware of our colonial position as Israelis, and the dangers such unequal political relationships carry, an important principle of our participation in the struggle is to do our best not to replicate the positions of occupied-occupier inside the movement. Though as Israelis the struggle is ours to fight, side by side with Palestinians, it is, in this colonial situation, definitely not ours to lead, and all major decisions are made by Palestinians.

Anarchists Against the Wall’s importance is simply in being there, as Israelis; its importance is the shattering of borders—be they borders of national loyalty, or the ones between protest and resistance. In Israel such acts were not at all an obvious thing prior to Anarchists Against The Wall, even for anarchists.

It’s kind of funny you mention that. It is well known that Muslims abstain from alcohol, but it is less known that devout Muslims also don’t smoke or take drugs, because the Quran forbids one from harming her body. I guess that’s where the stupidity of those hardliners who fluctuate towards fundamentalist Islam and try to give Straight Edge a religious touch draws from. In my opinion this trend is very counterproductive. I feel Straight Edge should be a passionate assault on our own mainstream culture rather than a way to connect our counterculture with fundamentalism.

I think it’s rather problematic to equate Straight Edge with just abstinence, but having said that, abstaining from alcohol can definitely help in Palestine, no doubt, but I don’t think Straight Edge is very relevant here. The non-Straight Edgers among us don’t drink in Palestine either, out of a guest’s respect for people’s culture.

After years of Israelis using cultural-exchange and “dialogue” as ways to strengthen and profit from the occupation, Palestinians are very suspicious of normalization; i.e. the attempt to form normal relationships between Palestinians and Israelis under the occupation, as if the terms are equal. While disrespect for Palestinian culture would have definitely been detrimental for the attempt to build trust, I think such trust can only be built from the understanding that we do not seek normalization, but rather that we wish to take part, in the most literal way, in the fight against the occupation. Through the years, this trust was and still is being built through mutual respect and the sincerity of our wishes to take part in the struggle rather than to talk about guilt.

You are right—no, the Palestinian masses won’t rally behind our libertarian causes, but this is not why we go. I understand anarchism not as an abstract idea confined to a hundred years of written thought, but, above all, as a fight against injustice in the here and now. I think that this is exactly what we are doing.

This does not mean, of course, that we don’t have our own limits and principles. For instance, while most Palestinians, obviously, aren’t exactly vegans, animal rights is very influential in the Israeli anarchist scene, maybe more than anywhere else in the world. I can remember a few times when this became an issue, for instance when we locked ourselves in a huge metal cage to block bulldozers from clearing the path for the wall, and one of the farmers brought a goat with him; or when donkeys are used to transport hundreds of kilos of olives during olive harvest. It is important for us to join Palestinians in their resistance, many times also at the price of ideological purity, but everyone draws her own line individually.

I think the answer for all three is struggle.

For anarchism simply because struggle is its essence, and will, I hope, always be its future. I don’t see anarchism as an escapist-utopian idea, but rather as one of the present; a never-complete pursuit of freedom and equality, with boundaries that are always expanding. It is not a movement based on the notion of “the good of man,” rather the opposite: I see it based on the notion that there will always be oppression to fight, including after “the revolution.”

As for Straight Edge—its intrinsic logic only has any meaning in the context of refusing society, in the context of discontent; as a tribal cry of war for the misfits and outcasts, the angry daughters of western pop culture.

And the Middle East? That’s just too sad a story. We’ve already talked about realpolitik long enough in this interview, but there is simply no option for this region other than struggle—it is too succumbed by imperialism and internal corruption to offer any other solution, if there is to be a future for this place at all. From the occupation of Iraq to that of Palestine, from oppressive “authentic” regimes (as opposed to the puppet regimes of Iraq or Afghanistan) to religious fundamentalism, the light of hope is a very scarce recourse in the dark tunnel of the Middle East.

As far as the Zionist-Palestinian conflict is concerned specifically, I am not an optimist here either. Every effort at peace negotiations so far has been cynically used by Israel to mask the perpetuation of its apartheid regime as attempts to end it.

In the long term, the two state solution could never offer true reconciliation as it offers no solution to the millions of Palestinian refugees and is based on a racist notion of Israel remaining an ethnocracy where Jews will inherently have more rights than others.

The only point of dim light is that while racist and rejectionist tendencies on the Israeli side are rapidly growing, voices calling for the replacement of the national liberation struggle with one for equal rights become, slowly but steadily, louder on the Palestinian side. However, these voices are still a long way from representing the mainstream of Palestinian politics. Even if the agenda of civil rights will prevail over the nationalist one, long years of struggle are ahead of us.