Towards a Less Fucked Up World:

“Towards a Less Fucked Up World: Sobriety and Anarchist Struggle” was first self-published as a pamphlet in 2003. The text proved to be pivotal for contemporary connections between radical politics and sobriety. The author, Nick Riotfag, revised the original version for this book and has added an afterword.

Nick Riotfag is an anarchist, queer, and straight edge activist/writer who lives in North Carolina.

Introduction

This zine is an ongoing project I’ve been writing in my head and on paper for several years now. Since I decided to become permanently sober several years ago, I’ve constantly struggled to find safe spaces; I hoped that when I started to become a part of radical, activist, and anarchist communities, that I would find folks who shared or at least respected my convictions. Instead, I found a painful paradox: radical scenes that were so welcoming and affirming in many ways, yet incredibly inflexible and unsupportive around my desire to be in sober spaces.

I have plenty of reasons for being substance-free that aren’t “political,” per se. Some are more personal or internal: I love my body and want to preserve my health; I’m personally terrified of addiction; I tend towards extremes, so I think that if I did drink or drug I’d overdo it; my family has had alcoholics and drug abusers who have ruined lives. Others are more pragmatic: as an activist I participate in actions that could put me at risk for arrest, and the legal risks of drug possession just aren’t worthwhile; I have better things to spend money on; and so forth. However, my primary reasons for choosing this lifestyle are specifically connected to my political beliefs as a revolutionary, a feminist, and an anarchist. I don’t think that most folks with whom I work on political projects realize or acknowledge that my choice to be sober isn’t just a personal preference or an annoying puritan dogma. This zine is my attempt to articulate why I consider sobriety a crucial part of my anarchism and feminism.

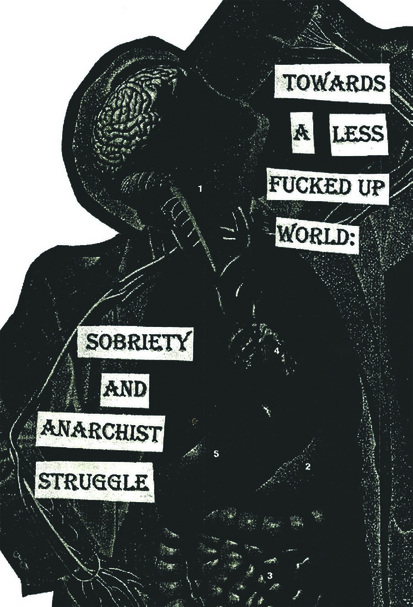

I’ve tried to put it together in a way that combines theory and analysis with my personal experience. The first few sections explore the connections I see between intoxication and different kinds of oppression (sorry if it gets a little wordy at times); the next bit talks about how intoxication fits into radical communities; then I offer two stories from my life and my reflections on them before the conclusion. (Image 17.1)

Image 17.1: Front Cover to the original Towards a Less Fucked Up World zine

I realize that sober folks have traditionally not been known for presenting our views respectfully, with open ears and loving hearts. I’m definitely among those who stand guilty of bludgeoning people with my beliefs. Hopefully this zine will at least in part rectify that tendency by explaining my views without judging or blaming non-sober folks or seeming to set myself up as superior to others. If it fails in this, I apologize in advance, and welcome folks to call me out on it. That said, please know that much of my anger that manifests in a “judgmental” or “preachy” tone comes from constant denial of safe space, refusal to recognize the legitimacy of our feelings and opinions, alienation in most social environments, and general ignoring of our concerns and desires and needs. I write with love and rage, and I apologize for neither.

A Quick Note On Words

I like the term “straightedge,” not because I’m especially invested in the bands and the scene, but rather because I like the way it places my decision not to drink or take drugs in the larger context of a positive radical social critique. Of course, I’ve found that most folks—probably many of y’all, too—have nothing but negative associations with sXe: macho white dudes beating up people, crappy music, super dogmatic and preachy assholes, or even anti-abortion extremists. Even though I completely reject all of those things, I still think there’s hope for reclaiming the term as something positive. But because for most folks I’ve asked it’s often more of a stumbling block than a help, I’m going to stick with “sober” or “substance-free” for the purposes of this zine.

Here are some definitions for some of the key concepts I’ll be talking about:

Masculinity, Rape Culture, and Intoxication

Dear readers: please know that this section includes discussion of sexual violence and other things that may be difficult or triggering for some folks. Please use self-care to determine if and when it makes sense to read this. Thanks!

I saw a billboard once as I was riding my bike through downtown New Orleans. It was advertising some kind of fancy liquor, whiskey I think. The slogan was, “It’s what men do.” The message was almost reassuring to me; the only possible conclusion, I supposed, is that I must not be a man. The mass media encourages folks socialized as men to affirm our masculinity through intoxication, specifically through capitalist alcohol consumption. The whiskey billboard I saw, along with Budweiser ads that show “male bonding,” various beer companies whose commercials use men objectifying women, and countless other advertisements, show alcohol as the common theme that links men as they engage in the most manly of activities. How surprising is it, then, that alcohol is almost always involved in some of the “manliest” pursuits of all—male violence against women, including domestic violence, sexual assault, and rape?

The relationship between intoxication, gender, and violence is complex. A significant proportion of gendered violence—specifically sexual and relationship violence against women—is committed by men while intoxicated. Of course, this doesn’t mean that intoxication causes violence, but it would be equally foolish to ignore the correlation. In heterosexual interactions, men who have learned from media and pop culture to understand themselves as initiators and seducers use alcohol as a tool for overcoming resistance both from the desired sexual conquest and from their own conscience. At the same time, in this harshly puritanical, sex-negative culture, many rely on alcohol as their only means of overcoming the shame they feel about our sexual desires. Generally speaking, I think that the broad dependence in this society on alcohol in the process of finding partners and having sex obscures our sexuality, negatively impacts communication, reduces our ability to give and receive meaningful consent, lessens the probability of safe sex practices, and supports rape culture. When this dependence, and all of the dangers it entails, connects with patriarchal notions of sexuality, including male senses of entitlement, the hunter/hunted dynamic, and “no means yes” myths, the result can be disastrous.

As a man, part of my decision to live a sXe or sober lifestyle stems from my recognition that patriarchy and intoxication culture go hand in hand. Intoxication is used as an excuse to justify (and legally, a mitigating factor in the prosecution of) a wide range of unacceptable behaviors, including sexual harassment and rape. In my personal experience, many people I’ve known—most often men—have significantly altered their behavior while intoxicated in ways that directly reinforce oppression (i.e. becoming more openly homophobic and misogynist in speech, more sexually aggressive, etc), and expected the fact that they were intoxicated to somehow alleviate their responsibility for these behaviors. The idea that being intoxicated somehow makes one less able to make rational and compassionate decisions should be a reason to abstain from using alcohol and drugs.

In saying this, I want to make clear that I do not intend to blame victims; there is absolutely no excuse for sexual or relationship violence, regardless of the intoxication or not of the assaulter or the survivor. I refuse to allow one’s intoxication to reduce one’s culpability for fucked up behavior. If there’s any possibility that drinking or taking drugs could increase, even the slightest bit, one’s capacity to be violent or abusive, then I consider that more than enough reason to be substance-free. If you’re making the decision to get intoxicated or fucked up, and you care about living your ideals in any meaningful way, you need a plan for how you can be held accountable, by yourself and others, for how you behave when you choose to do so, in sexual situations and beyond.

I want to emphasize that this is not something that exists only in the “mainstream,” as if anarchist or radical communities were immune from its effects. Women in our communities are speaking out about sexual harassment and assault and rape at the hands of “radical” men. In virtually every case of which I’m aware, alcohol played a major part in these incidents. One of my dearest friends has been sexually harassed on multiple occasions and sexually assaulted by intoxicated anarchist men, who, while sober, expressed serious and firm anti-patriarchy convictions. Yes, anarchist men, feminist men, men who say they are fighting patriarchy with all their might, that means us: if we take seriously the charge to be responsible, anti-sexist allies to women, I strongly believe that we must look very critically at the ways we get intoxicated.1

This pattern of boundary-crossing while intoxicated doesn’t always fall predictably along gender lines. Sometimes women take advantage of men sexually using intoxication; at times the intoxication of both or all parties makes it difficult to sort out accountability; sometimes participants don’t neatly fit gender boxes and power dynamics play out with more complexity. Alcohol-based coercion and blurry consent also exist in same-sex relationships and interactions, in some especially difficult to escape ways due to the particular stranglehold of intoxication culture in queer communities.2 Although the conditioning that men receive in our patriarchal rape culture contributes to higher rates of men crossing boundaries without consent, all of us—men, women, and others, transgender and non-transgender—have the capacity to violate others. But more importantly, we also all have the capacity to become allies in the struggle to undermine patriarchy and construct a society based on consent. I think that because of this, all people who are committed to fighting rape culture and patriarchy can benefit from critically examining our patterns of intoxication, and discussing ways to be held equally accountable for behavior while intoxicated as well as while sober.

Oppression and Anesthesia

Maintaining privilege and continuing to oppress a group of people is only possible when oppressors can see the people they oppress as less than fully human. A major tactic in the dehumanizing process is the oppressor’s anesthesia, numbing oneself so as to be unable to empathize with the people they are relegating to a sub-human status. Mab Segrest wrote a moving essay about how a key strategy for maintaining white privilege is the anesthesia of white people towards the suffering of people of color, through distance (out of sight, out of mind), rationalization, intoxication, and other methods. Likewise, masculinity operates by forcing men to stay detached and impassive in the face of physical or emotional pain, setting up sensitivity and empathy as “female” (and therefore inferior) characteristics. Constructing masculinity as unfeeling—anesthetized—makes possible the incredible suffering inflicted by men upon women (and other men) through violence, rape, child abuse, denial of access to birth control and medical care, the patriarchal nuclear family, and so many other means. In this context, it makes perfect sense that intoxication would be linked with masculinity. Intoxication often reduces the ability of people to empathize with others, an integral part of being an oppressor.

A friend of mine pointed out that when she was in high school, most of the kids that she knew who had any idea of what was happening in the world were getting completely fucked up as often as they could to neutralize the pain of that awareness. I can understand how activists, who (theoretically) operate by refusing to ignore the suffering and oppression in the world, face an incredible temptation to try and numb themselves, even temporarily, to the pain they see and feel and struggle against every day. However, I also strongly believe that if everyone in our culture was both fully aware of the full extent of how fucked up our society is—and refused to simply ignore the pain of that awareness though various methods of intoxication and anesthesia, from booze to television—then people simply would not stand for it.

Even providing for the (minority, I think, of) people who are simply cruel and hateful, I truly believe that a population honestly facing the realities of poverty, oppression, and misery rife in this culture cannot do so with both clear heads and clear consciences. When heads are not clear, clear consciences become less and less important. When people refuse to be numb and truly live the pain of this culture, it motivates action. I believe that our task as activists or people who feel a call to change this culture is first and foremost to be open to that deep pain, to feel it and mourn it and hate it, so that it lights fires in our chests that burn for our participation in revolutionary struggle.

Youth Liberation and Sobriety

The most well-known icon of sXe, the Xs that some edgers draw on their hands, originated out of a gesture of solidarity with youth. To this day, kids at shows and other all-ages events that serve alcohol often have black Xs drawn on their hands by the people taking money at the door as a sign that they aren’t allowed to drink. In the early 1980’s, when Minor Threat began bringing the substance-free message to the punk scene, people who noticed kids marked with these Xs as symbols for prohibition of alcohol started drawing them on their hands, regardless of age, to show solidarity with youth and a commitment to sobriety. Because of the prevalence of intoxication culture, shows and other events often cost more for young kids, or don’t allow them in at all. The drinking age serves as a legal tool for enforcing segregation and discrimination directed towards young folks, setting up an entire system around consumption of alcohol that simultaneously devalues youth and glorifies intoxication, constructing it as “mature” and advanced and all of the other positive traits associated with adulthood.

As a result, among young people, the mystique of intoxication culture leads to semi-secretive consumption of alcohol and other drugs, often to a destructive degree. For kids around the ages of eighteen to twenty-two or so, just before and after the drinking age, the ability to finally partake in the highly coveted “privilege” of intoxication culture leads to cults of hyper-intoxication, reinforcing the mystique even more. When the destructive consequences of getting fucked up manifest dramatically in young folks, as shown by the number of deaths from binge drinking, clueless and patronizing adults wag their fingers and bemoan “peer pressure” as the cause, when it’s blatantly fucking obvious that the causes lie in their own actions.

The entirely adult-constructed mystique around intoxication, hypocritical and inconsistent policies promoting potentially fatal intoxicants while violently suppressing less harmful ones, and the oppression and devaluing of young people in general frequently lead to the desire to emulate the destructive fucked up patterns of adult intoxication with the vehemence of youth. Fuck “peer pressure”—I’ve felt consistent and unrelenting pressure from every sector of adult society to intoxicate myself through every possible means for as long as I can remember. Do adults honestly think that a “drug education program” in 5th grade and some condescending guest speakers in a high school health class would cancel the effects of an entire social system based on oppression requiring intoxication and anesthesia to survive?

My decision to abstain totally from intoxication culture has a lot to do with my desire for youth liberation. Maybe I don’t want the privilege that comes with adulthood to destroy my body legally. Maybe I don’t buy the argument that only adults—being naturally superior to kids, according to adult chauvinist logic—are responsible enough to handle getting fucked up. I think the impressive thing is being strong enough to survive without getting fucked up—if becoming an adult means accepting the need to numb myself into accepting the status quo, then fuck it, I’m following Peter Pan and never growing up.

Intoxication and Social Life

Seriously, one of the reasons why living in a community that drinks constantly bugs me is that it makes conversation so damn boring! I can hardly ever hang out in a large group without conversation turning for a substantial period of time to drinking, getting fucked up, what so and so did when they were fucked up, how fucked up so and so’s going to get, blah blah blah. Who fucking cares? Are people really so boring most of the time that they don’t merit conversation without corporate-induced altered consciousness? Can we really not think of anything more interesting to talk about than our self-destructiveness? What about our dreams, our passions, our crazy ideas and schemes, our hopes and fears? I hate going to parties where intoxication numbs individuality into mush, so that I can have the same mindless banter with 100 people but not a conversation of any substance with a single person. Am I anti-social for staying home with one good friend or a book when that’s the alternative?

Beyond boring conversation, dependence on alcohol limits our social lives in other ways. In bar culture, public interaction is limited to contexts where we have to buy something in order to spend time with other people. It makes us less well equipped to enjoy one another’s company in ordinary mindsets or without corporate intervention. We bond over buying, consuming, numbing, and things rather than creating, experiencing, feeling, and personalities. Instead of challenging it, we accept the proposition that we need consumer capitalism to be able to “loosen up,” have a good time, and get past the hang-ups and self-restraint that constrain our lives.

Intoxication and Corporate Culture

I know a disturbing amount of folks in radical communities who spend their entire income on alcohol and tobacco. People who shoplift from the local food coop because they don’t want to pay for food will head down the street to the chain convenience store and pour the tiny bit of money that they do have into some of the most wicked fucking corporations in operation today. There seems to be an incredible blind spot around tobacco and booze with regards to ethical consumption; kids who’ll demonstrate against Wal-Mart or Exxon for their labor or environmental practices will then turn around and buy cigarettes and beer from stores that have devastatingly negative impacts on local communities and that were produced by companies that are central to everything that’s awful about global capitalism. Kudos to kids who at least make an effort to buy local, grow/brew their own, and such, but the industry feeds off of them just as much, knowing that the more dependent they are on chemical stimulation the less they’ll care where it comes from.

Growing tobacco is incredibly destructive to land; after three years of hosting a tobacco crop, soil is so depleted that nothing can be grown there for the next twenty. Tobacco (grown by indentured servants and slaves) was the single reason why the first English colony in America managed to survive, and with increasing numbers of white settlers requiring new swaths of land every three years to sustain the colonial economy, it’s not a stretch to say that tobacco-motivated theft of native land was one of the major catalysts for the genocidal campaign against the indigenous people of this continent that continues to this day. This process continues around the world, as tobacco corporations constantly absorb new plots of land to feed the cravings of the millions of addicted around the world. To get this land, corporations steal it from public lands or indigenous tribes, “buy” it from peasants so impoverished by global capitalism that they have no choice but to sell it (so that they can be more easily forced into the new factories), or convert land that previously grew food crops that actually nourished rather than poisoned people.

In most nations in the global south, tobacco is flue-cured, a labor-intensive process that requires massive deforestation; one researcher estimated that tobacco cultivation and processing accounted for one of every eight trees cut down in underdeveloped countries. As more and more land becomes ecologically devastated from tobacco cultivation, the cycle accelerates, less and less land is available for food production, and more and more deadly chemicals and genetically engineered strains are required to grow anything. Tobacco companies offer subsidies and technical support to farmers in underdeveloped nations to switch from food to tobacco, and since IMF structural adjustment programs have decimated public support of agriculture, many farmers have no choice but to convert, accelerating hunger within their nation and increasing their dependence on the global capitalist market. Tobacco is at the heart of the horrifically pathological global system of capitalist agriculture that prioritizes the right of First World people to poison themselves over the right of Third World people to eat.

Intoxication In Oppressed Communities

Drugs and alcohol are used as colonial weapons against folks of African descent in the United States. Frederick Douglass pointed out in his slave narrative that on holidays, masters would encourage slaves to drink to excess specifically to skew their perceptions of what freedom was and to promote passivity the rest of the year. From absentee-owned liquor stores in black neighborhoods to the CIA’s introduction of crack as a weapon against black communities, white people have profited from the economic drain, physical debilitation, and social conflict and violence exacerbated by alcohol and drugs in black communities. The black revolutionary tradition in the US has strong tendencies towards sobriety, from the Malcolm X to the Black Panthers to Dead Prez, drawing specific links between black oppression and intoxication culture.

The native communities that survive in North America are almost all absolutely devastated by alcoholism. Alcohol abuse has severely disrupted what positive community structures have survived the European genocide. For the past several hundred years, alcohol was used by opportunistic whites as a way to con native people into signing “treaties” robbing them of their land, and as an intentional strategy of sowing discord into previously unified, harmonious, and sober communities. Currently, alcoholism is one of the leading causes of death among native people; around reservations that have prohibited alcohol, primarily white “drunk towns” have sprung up with dozens of bars and ABC stores just past the reservation borders to turn indigenous addiction into capitalist profit, often with fatal consequences.

Queer and trans communities struggle with astronomically high rates of alcoholism, due both to an attempt to escape the pressure of hiding their sexuality from family, friends, and society, and due to the emphasis on alcohol as a form of recreation throughout mainstream queer culture. Beer companies are among the largest sponsors of “Pride” celebrations and advertise extensively in queer publications; in most areas of the US, the primary social spaces for queer-friendly (or even queer-safe) interaction are bars whose primary function is selling intoxication. One of the first specifically gay and lesbian organizations in many towns is a chapter of Alcoholic Anonymous. Substance abuse rates among queers are also severe, as untold numbers of ravers and club queens burn out on cocaine, crystal meth, ecstasy, and other substances. The epidemics of AIDS and other STDs continue, in spite of the incredible efforts of educators and activists throughout the country, largely because of risky sex while intoxicated. For sober queers, virtually no physical or social space exists.

Intoxication and Radical Communities

The reluctance of “activist” or “anarchist” or “radical” communities to acknowledge how fucked up (pun intended) intoxication culture can be genuinely baffles me. Ever since I got involved in radical politics, these connections have seemed obvious to me, but the fact that so few people appeared to agree made me wonder whether perhaps I was the one who had it all wrong. Alcohol (ab)use, tobacco smoking, and varying degrees of drug use have been central institutions in the lives of the vast majority of the radical folks with whom I’ve worked. Only recently have I begun to make connections with other sober radicals apart from scattered acquaintances, and nearly all of us relate to the feelings of isolation within our communities, alienation from our peers, and frustration with the lack of support we feel for sober safe spaces.

Yet the fact that we’re the few, the lonely, and the sober by no means indicates that we’re the only ones who see or complain about the problems caused by intoxication culture’s infiltration into radical communities. My individual conversations with many distinctly non-sober folks often reveal a genuine anxiety about the negative consequences of their personal and the scene’s social dependence on drugs and alcohol. My personal experience and the experience of numerous women, people of color, and queer and trans people with whom I’ve discussed the issue confirms to me how hypocritical people can be who claim to be fighting oppression yet participate proudly in intoxication culture. More and more, this issue seems like the elephant in the corner that no one’s willing to point out.

I think it’s high time (ha ha) that our communities started meaningful dialogues around issues of sobriety and intoxication—and there are going to have to be non-sober allies who step up and take active roles alongside the substance-free folks for it to work. We need to be negotiating agreements for collective houses and spaces, social gatherings, shows and events, and other spaces in our lives that respect the needs of folks both sober and not, with a particular emphasis on respecting the requests of women and trans folks, whose needs are least frequently considered in developing community standards. This is not something that many of our communities are used to, but in my opinion it’s absolutely essential. This process has the potential to be a revolutionary transformation, as we move away from a loosely associated group of people who work together to an actual community where we respect each others’ needs and hold each other accountable.

Intoxication and “Autonomy” vs. Accountability

In the process of developing community agreements, some folks may feel that they’re being denied their “autonomy,” their right to live their own lives how they want, including the right to get fucked up if they so desire. Personally, I wholeheartedly support the right of any individual to fuck themselves up with chemicals as much as they want to, without sanction from the state, organized religion, or self-righteous zine writers. However, I only support that right so long as you contain the destructiveness of your choices to yourself; as someone wise once said, “Your right to swing your fist ends where my nose begins.” And I’d argue that very few people who do choose to get fucked up honestly and completely look at how their choices to do so impact others, particularly oppressed folks.

From the financial support of really fucked up corporations, to the targeting of people of color and queer communities and the increased rates of addiction and devastation in these communities, to the relationship between intoxication and patriarchal masculinity, to the fucked up behavior towards women that so often arises with intoxication ... it’s NOT just a simple personal choice you make yourself, in a bubble, to smoke or drink or take drugs. There’s an incredible amount of baggage that goes along with the decision to get fucked up that activist communities, in my experience, rarely acknowledge.

Some anarchists see anarchy as the ability to do whatever they want without having to be accountable to anyone else for their actions. I personally think that that kind of attitude is just the standard American “rugged individualism” bullshit repackaged as a faux-radical alternative, because it doesn’t challenge the fundamental alienation from each other we suffer under capitalism and the state. If our society replaces genuine community with consumer culture, authority, and oppression, that kind of anarchism simply rejects any idea of community at all. For me, anarchism is about replacing the false community of the state and consumer culture with a community based on mutual aid rather than competition, gift economy rather than capitalism, and collective agreements based on full consent and voluntary association rather than rules or laws based on state coercion and violence. Instead of being accountable to authority, I want us to actually be accountable to each other. A pretty important part of that is being able to come together as radical communities and have conversations about how alcohol and drugs impact our work, our spaces, our relationships, and our unity, and to figure out what sorts of agreements and boundaries make sense for us.

As a perfect example of the kind of community-based response to alcohol and drugs I’m talking about, look at the Zapatista movement in southern Mexico. During the weeks I spent in Chiapas learning about their struggle, I learned something that most of the kids in the Subcommandante Marcos t-shirts don’t mention: all autonomous Zapatista communities are 100 percent alcohol free. No alcoholic beverages are sold or consumed in any of the autonomous municipalities, and on the signs indicating that you are entering Zapatista territory in rebellion against the Mexican government, many specifically say that these are alcohol and drug free spaces. I learned also that the reason for this is because it was a central demand of the women involved in discussion about the new society they were building. Mexican women feel most acutely the effects of alcoholism, in terms of domestic and sexual abuse, and because being financially dependent on men in a patriarchal society means that when husbands spend the family’s money on booze, the wife has to struggle to pay for food for her and her children. The director of a feminist collective in San Cristóbal with whom I spoke said that male alcohol abuse is one of the central problems facing women in Mexico today.

Consequently, the communities agreed to the demand of the women for drug and alcohol free communities, in spite of the fact that many of the men wanted to be able to drink. Some villages even split around this issue. Currently, the no-alcohol agreement is enforced by the community, and it is almost always respected; folks who refuse to respect the prohibition are ostracized or, if they refuse to change their behavior, face expulsion from the community (incidentally, it’s almost unheard of for it to reach that point). A traveler I met who had passed through Guatemala and parts of southern Mexico on his way to Chiapas mentioned that in most of the rural villages he’d passed through, the majority of the men would be drunk by 10AM, every day. The Zapatista communities, he observed, had a completely different vibe; people got far more done and treated each other with more respect.

I mention this example for a number of reasons. For one, I think that many anarchaholics who supposedly idolize the Zapatista struggle could stand to learn about how those communities deal with alcohol and drugs. Also, I suspect that a lot of North American anarcho folks might find such a prohibition “authoritarian” or worse. This gets at the heart of how I see the difference between hyper-individualist and community-based anarchism. There’s nothing authoritarian, in my opinion, about an agreement reached collectively to abstain from individual behaviors that the community collectively decides are harmful to itself as a whole. The key to the Zapatista autonomous project is that it’s totally based on voluntary association; no community or individual is forced to participate. Many villages have chosen not to be an official part of the network of autonomous municipalities if they don’t consent to all of the agreements made by the Zapatista movement, and that’s fine.

Furthermore, the Zapatista agreements on alcohol are an example of actually acknowledging and directly respecting the autonomy of women. How many anarchist groups or communities in the US who claim to be feminist have actually adopted the desires and needs of women into their practice—or even bothered to ask? All in all, the people involved in that struggle decided to place the good of their community, as determined through consensus, above the unlimited “freedom” of individuals to do as they please. I would challenge our anarchist communities in the north to think critically about our priorities and grapple with these difficult questions about individual and community, autonomy and accountability.

Story #1

My primary activist community when I first moved to the town where I now live operated out of a collective bookstore, an awesome space full of radicals working on positive projects. Just a month or two after I’d become very involved, I was invited to attend a retreat with the board of directors at a beach house several hours away from where we lived. I’d heard people joking about how much alcoholic fun they were going to have there, which immediately made me feel unsafe. The facts that I don’t drive and would have no way to get away if I felt unsafe, didn’t know many of the people involved very well yet, and was the only young person all made me very nervous about the situation, and I expressed my misgivings to a friend who worked at the store. She assured me that there wouldn’t be much alcohol, that people wouldn’t be getting too drunk, and that if I felt unsafe she would be available for me. With that assurance, I somewhat reluctantly came along.

On Saturday night, two people left to get alcohol, returning with four cases of beer and several bottles of liquor. Everyone except for me was an adult and everyone except for me drank pretty heavily that night, including my friend who said that she would be available for me. I felt very uncomfortable, but I didn’t have any way to leave, any idea where I was, or any alternatives for entertainment, so I just sat through it. The next morning we got started with our work hours later than we’d planned to because folks were hung over and wanted to sleep. When we debriefed at the end of the retreat, I mentioned that one thing I would have changed was to have less alcohol, but I didn’t feel comfortable enough to express how seriously I felt alienated and unsafe, or ask for ways to hold the group accountable next time. No one discussed it further or followed up with me about my discomfort. I don’t know how to breach the subject without putting people on the defensive, and I feel like I’m being selfish, whiny, hypersensitive, a “party pooper,” or anti-democratic by expressing how I feel about it. I don’t necessarily think that it would be fair to ask the group to completely ban alcohol at the retreat, especially given that every single person but me of a group of fifteen or so enjoys drinking, yet the only alternative seems to be the default of me faking smiles and sitting uncomfortably through situations that make me feel unsafe and alone.

One way to address such a situation for sober folks to feel safe and able to still participate might be to ensure in advance that at least one or two other people will be there who will commit to stay sober for the night (whether or not they usually do). That way, the group could still drink if they chose to do so, while the sober person can still have a way to feel safe with someone, or leave if necessary and not feel totally isolated. I would suggest finding someone you trust a lot and know will be committed to an evening of sobriety, and to be sure to ask them to commit in advance, so that they haven’t built intoxication into their expectations for the activity. Other possibilities include asking all of the people involved to make it an alcohol-free occasion, particularly if it’s a small group or event, or simply declining to attend and making clear that the presence of drugs and alcohol is the reason why you’re not coming. Whatever you decide, it will probably work best to calmly and specifically explain your discomfort, and to take care not to judge or make assumptions about other people’s behavior. If people committed to sobriety stop making excuses, staying home, or remaining silent when they feel unsafe, hopefully we can start a dialogue about issues of intoxication in activist communities that will help create social space for substance-free folks.

Story #2

I attended an environmental defense action camp for a week with about 150 kids in the mountains. I was pretty nervous about going out there with no way to get out of the situation and a big crew of rowdy booze-loving primitivists, but I decided it was more important to go and to learn the skills I could learn. Things went surprisingly well for most of the week; half way through there was an alcohol-light campfire sing-along that was a blast. On the last night, there was a big party planned, with all sorts of preparations made for multiple kegs and beer runs and home brew and more. Amazingly, the organizers were really concerned with ensuring that the folks who wanted to remain sober had a safe space, and planned to make a clear community agreement in advance with specific dry zones, etc. The full-group meeting broke off for dinner before the conversation could take place, so a group of fifteen or so folks interested in seeing that sober spaces were secured stayed late and talked through options; even more amazingly, almost all of the group were folks who were planning to drink, but wanted to be allies to the sober folks. After a frustrating and long set of negotiations, a separate campfire area that was to be not only alcohol free, but only for folks who had not had any alcohol that night, was set up, with individuals committing to gather wood and dig the pit. I was pretty thrilled, having never before been in a space where people even acknowledged that sober people had valid needs, let alone worked hard to create a distinct safe space and make it a priority.

So I hung out that evening at the sober campfire ... along with about five or six others. We were a pretty low-key bunch, and I for one felt distinctly glum. It was nice to have the company, but I couldn’t shake the feeling of being quarantined. We were only a few hundred yards away from the massive drunken bonfire, with over a hundred kids hollering and stomping about, though none of them could come to our fire, and most of us didn’t feel remotely comfortable going over to theirs, even though most of our friends and crushes and lovers were over there. After thirty or forty-five minutes, most of us had drifted off to our tents, the screams of the revelers echoing in our ears. I sat morosely by the dwindling embers for a long while, trying to figure out why I felt so dejected. Isn’t this what I wanted, our own separate “safe space”? I felt guilty for not sufficiently appreciating what was undoubtedly the most comprehensive effort to address my needs that had ever been made in a radical space. Finally, as the main party in the distance tailed off into isolated voices fighting and cursing or sobbing, I ambled off to bed, feeling as lonely and isolated as ever.

That experience represented a mixture of positives and negatives, and could point towards some constructive solutions. On the plus side, organizers and participants (at least a number of them) did make a substantial effort during the day to plan a sober alternative space that would be safe; on the minus side, the larger group wasn’t engaged in that process, and most folks in fact were simply informed that if they planned to drink, they weren’t permitted to go in a certain area, reinforcing the absolute sober/not dichotomy which felt isolating to me. On the plus side, many non-sober allies stepped up to make sure that safe spaces were provided, which I think is crucially important; on the minus side, the allies didn’t extend their support into actually participating with the sober folks and abstaining themselves, except for one person, and not many of the sober folks for whom the space was being designed actually participated in its planning. On the plus side, the space was created and respected; on the minus side, there were hardly any folks there, and it wasn’t much fun, though everyone agreed they were glad it was there. The proximity to the “main” drunken party, the severely disproportionate number of non-sober to sober folks, the lack of actual activities beyond a space and a campfire, the feeling of being quarantined, and the general lack of support among many camp participants (excepting the organizers and wonderful allies) made the reality of the sober space fall far short of the expectations.

To improve the situation in the future, a few things that could be changed:

Conclusion: The Beginning?

Hopefully some of the ideas in this zine have been helpful, or provocative, or maybe showed things in a different light, or gave you some starting points for addressing the concerns of sober folks in your communities. I wouldn’t expect most folks to accept or agree with everything I’ve written, but with luck it’ll open a few minds and hearts and start some debates. Also, some of us are thinking towards developing a sober support network to share resources, develop propaganda, start conversations in our communities, identify safe spaces, and support each other when we feel isolated. It’s a long way towards a less fucked up world, but with honesty, dialogue, and each other’s support we can begin heading that way. Until then,