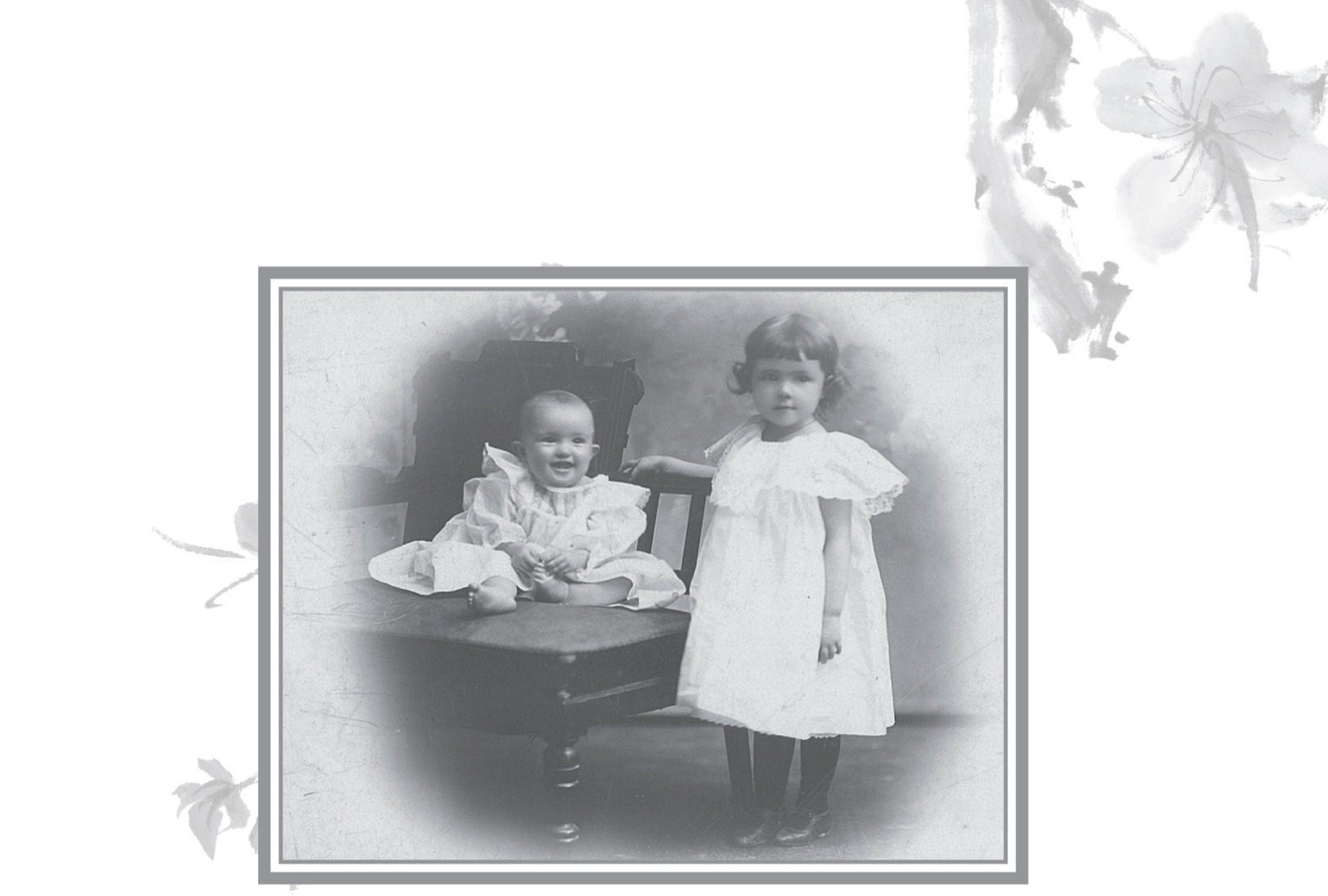

Anne and baby Mary Goetchius.

Mary Elizabeth Goetchius

When I’m asked about censorship, I recall that my parents, conservative Presbyterian missionaries, never censored what we children read. In fact, when I was eleven or twelve, Mother would hand me the book-of-the-month selection that she’d failed to return before the deadline and ask me to read it to see if it was worth her time. When I was eleven, she gave me a copy of The Yearling, a Pulitzer Prize–winning book she had read. She knew it contained profane language and “inappropriate content,” but she gave it to me because she knew I would love it. I did love it. Reading it as an adult I see how much that book has influenced me as a writer.

Mother was a big fan of my books and promoted them to the extent that I wondered after she died, who was going to buy them now that she was gone. When I got word that The Great Gilly Hopkins was the Newbery Honor book (that year for some mysterious reason there was only one), I was told that I couldn’t tell anyone until after the official press conference. I decided that one’s dying mother didn’t count as telling and called her at once. She could barely speak by then, but when I told her the news, she asked in the playful voice I knew so well: “That naughty child?”

Mother was born in Waco, Texas, but that didn’t make her a Texan. She always said that her father left Georgia and took his family to Texas to seek his fortune, but all he found was her, so they all went back to Georgia. They settled in Rome, where her father’s older brother George was pastor of a Presbyterian church. She was named Mary and was the middle of her parents’ three girls. Anne, the oldest, was an artist who ironically always suffered from poor eyesight. Helen, the youngest, was a bit of a rebel who often caused their straight-laced mother anxiety. But my mother was, it appears, the “good child.” Grandmother referred to her as “my little missionary,” pointing her at an early age toward service as a “foreign missionary.” In addition to the two eldest brothers who died in the Civil War, her father had two other older brothers—George, the minister, who was elected for a term as Moderator of the General Assembly of the (then) Southern Presbyterian Church—and Henry, a prosperous lawyer, who, being childless, wanted to adopt my mother. Henry never quite forgave my grandfather for not giving up one of his daughters (after all, he had a surplus) and at length adopted a son who inherited his entire estate.

Mother never minded being the daughter of a respectable, but certainly not wealthy, insurance and real estate salesman. As a child I often begged for stories of the “olden days,” when she was young. (My own children, referring to my youth, would say: “Back when you were alive, Mom . . .”—protests that I was still alive notwithstanding.) Mother always spoke with delight about growing up on Third Avenue in Rome, Georgia. Everyone seemed to live across the street from the Goetchius family. There was Uncle George and after his death in 1900, the new Presbyterian pastor, Dr. Sydnor, and his family with children roughly the same age as the Goetchius girls. Woodrow Wilson’s first wife grew up there, and Mother remembered her father, an elder in the Presbyterian church, acting as a pall bearer when Mrs. Wilson was brought back to Rome to be buried. There was, supposedly, a thank-you note from the president that never surfaced—much like the many Abraham Lincoln letters floating around that lived on in some family’s legend but not in its archives.

I was most envious of the neighborhood group of eight or nine girls just her age. Mother was an active member of the Third Avenue Gang, who had “spend-the-night parties,” progressive dinners, went to baseball games; in short, did everything together. One of the girls had a dollhouse in her backyard that became the gang’s clubhouse and the center of their activities until well up into their teens. When she talked about her childhood friends I was always envious. The idea of living in the same house for all your childhood and having the same knot of devoted friends seemed magical to me, who had lived in thirteen different places by the time I was thirteen. Years later, she went back to Rome for a reunion of the Third Avenue Gang, one of whom had married an heir of one of the early Hawaiian missionary families and another whose son wrote racy novels that had Rome in a twitter.

Summers as children we would go to the farm in Virginia where our spinster aunts and bachelor uncles were strict maintainers of good behavior, but the Goetchius girls would go to Eufala, Alabama, to visit their beloved aunt Anne or aunt Annie, as they called her. (I grew up thinking her name was “Aunt Tanny.”) She was Grandmother’s older and only sibling. As children, one of our witticisms was “Eufala? I picka you up.” Annie lived on a farm and produced six children and a brood of descendents, most of whom my generation never met. The exception was Cousin Wade Herren, known in the family as “Apple,” since it was accepted that he was the “apple of his mother’s eye.” Wade became a general during World War II, and we met him when he was stationed in Washington sometime after the war. He told us proudly, not of his exploits during the war, but of how honored he was to be the military escort for Princess Elizabeth on her official visit to Washington not too long before she became the Queen of England. “Beautiful manners. Just like a lovely young Southern girl,” he enthused.

The Goetchius girls loved the farm with their many cousins and all the African American field and house help there. On the Herren farm the children could run barefoot and take the pony cart out to the field and fill it with watermelons, hoping, perhaps encouraging, one to roll off and burst so that they could sit down and eat it in the middle of the path.

My grandmother Elizabeth Gertrude Daniel Goetchius was known as “Trudy” when she was a child, a playful nickname that seemed totally unlikely to me, who only knew her as a forbidding figure. I always called her “Grandmother Goetchius” or at least “Grandmother,” never Granny or Grandma or Nana or any of the diminutives by which my friends spoke fondly of their grandmothers.

I never knew my grandfather Charlie Goetchius, and it is one of the sorrows of my life. In his picture—I’ve only seen one—he’s a man I know I would have loved. He had red hair and a bushy mustache to match. I think I can see a mischievous light in his eyes, even in a formal photograph. Aunt Helen told me that she was “his girl,” and I believed her because I imagined he would have admired, not feared, that rebellious streak in his youngest daughter. An adventurous man of sorts, he was one of the first people in Rome to buy an automobile. Since Anne’s eyesight was poor, and Helen was too young, he decided to teach his daughter Mary how to drive. The lessons ceased abruptly when Mother drove his new Ford through the plate glass window of the local drugstore. Though only the window and the auto suffered damage, she didn’t take up driving again until she was in her fifties, when she and I took driving lessons from the same instructor after my father had given up on both of us. Ironically, it was Anne who soon afterward became an expert driver and was the first young woman in North Georgia to drive in parades and funerals.

Just before Anne was set to go to college, a relative came to be president of Shorter College, a half-hour walk from their Third Avenue home. After graduating, Anne went off to art school in Boston. Mother was barely sixteen when she entered Shorter, where she studied biology, having decided that she wanted to be a doctor. Doctors were badly needed in China, which she seemed to have decided early on would be the place to spend her life. Then during her senior year she was summoned out of class and told that her father was dead, felled by a massive heart attack for which there had been no warning.

Not only had she lost her father, she had lost any hope of becoming a doctor. There was no money for medical school and besides, how could she leave her mother at such a time? The solution was to find a teaching position in the area. Helen was still at home, so she taught that first year in Clinton, South Carolina, but when Helen left to go to nursing school, she returned to Rome to be with her mother.

By then America was at war. Along with several of her friends, Mary worked in the Red Cross/YMCA canteen. Dressed in blue uniforms with white veils, the girls were on the platform when troop trains came through. Summer was particularly exciting because the nearby orchards would send bushels of peaches to the station. The girls stood beside each car with a bushel of peaches to hand them out when the train stopped. Mother described the “whoop of the men, mostly from the north, when they piled off the cars and saw us canteen girls presiding over the peaches. It was especially fun at night when we had flares.”

Three of the girls, including Mary, loved the canteen work, and applied for an assignment overseas. They were only twenty-three and the minimum age was twenty-five, but the New York interviewer said there was a bill before Congress to lower the age, and when it passed, she would put their names at the top of the list. When the Armistice was signed in November Mother confessed to a tinge of disappointment in the midst of the rejoicing. She would not be going to France after all.

Several weeks later a wire came asking if she would be interested in an overseas assignment. Canteen workers were still needed, as the army would be in Europe for some time.

Once when we were children we were playing either Old Maids or Flinch, and I realized Mother was shuffling and bridging the deck like a riverboat gambler I’d seen in a movie. “Where did you learn how to do that?” I asked. She visibly blushed and confessed that on the boat taking her to France in 1918, she had learned to play bridge and dance—two activities her own mother would certainly have frowned on. But the chaplain in charge of the volunteers said that they would be needed skills when they arrived in France to entertain the troops.

When I was an adolescent, Mother told me about the chaplain, a kind man that all the young women liked and admired. Then one night after the dancing lesson he asked Mary to come down to his cabin for some forgotten purpose. “I was so naïve—he was the chaplain, after all—so I went. I had no idea . . .” Once there, the chaplain closed the door and threw his arms around her. Alarmed, she jammed the heel of her pump into his foot. He let go with a howl and she fled. The incident was never spoken of again until she had daughters of her own. I can remember at about thirteen staring wide-eyed at my proper mother when she thought it time to tell me this cautionary tale. I never had to utilize the heel-of-the-shoe trick myself, but I think Mother would be gratified to see that I passed it on to Lyddie Worthen for her use against her lecherous floor boss at the Lowell mill in my novel Lyddie.

Mother remembered her time in France as fun. The war was over and the troops were mostly on vacation. I can only assume she put her card-playing and dancing skills to use and had no more occasions on which to employ her foot-stabbing technique.

She had learned in Clinton and in Rome that she did not want to be a teacher, so on her return was delighted to take a job as a YWCA secretary in Petersburg, Virginia, which was near a large army post. But she couldn’t forget that she had planned for most of her life that she would be a missionary. She went over to Richmond, where there was a Presbyterian seminary and a new school for training women for church work, as the seminary did not enroll women in 1921. The president of the General Assembly’s Training School for Lay Workers (as it was then called) was a friend of her uncle George’s, and he advised her to go to Greensboro, North Carolina, to a church that had recently lost its Director of Christian Education.

She had hardly settled in Greensboro, when Dr. Edgert Smith, head of the denomination’s foreign mission board and a friend of her father’s, came to visit the church. The first thing he said to Mother was: “Where is Charlie Goetchius’s daughter who was going to China?” “I’m the one,” she said. “Well, daughter,” he said, “you’re not getting any younger.”

Dr. Smith not only got her released from her new job, but he persuaded the church to give her a scholarship to the Assembly’s Training School.

And that was where she met my father, which is the beginning of our family story.

Children in the same family have different parents. And even the same child will seem to have a different parent at a different stage in his or her life. After I was grown, my mother and I often tangled. We had a running controversy about clothes. She was very unhappy that I would not buy her grandchildren “Sunday clothes.” My argument was that we couldn’t possibly afford fancy clothes that could only be worn on Sundays and then not even every Sunday, clothes that would be quickly outgrown and might or might not fit a younger sibling. During the early seventies, I shocked her when she realized I, a minister’s wife, wore pants around the house. “Suppose one of the women from the church should come by and see you,” she said. She couldn’t believe when I retorted that at our church in Takoma Park, Maryland, a number of those lovely church ladies were wearing polyester pantsuits to church services. She was hurt and puzzled when my husband joined African Americans marching for the right to vote in Alabama and spent several nights in the Selma jail. “That’s not the Alabama I know,” she said. And until tapes revealed that President Nixon was a world-class cusser, she defended him against all my charges. But there is a great deal of my mother in Susan Bradshaw, Louise and Caroline’s mother in Jacob Have I Loved. It is no accident that I was writing the book while my mother was dying. The pivotal scene where Louise confronts her mother and her mother’s word allows her to leave both the island and her lifelong envy of Caroline could not have been written if I had had a different mother.

One story to prove my point. I was nine years old and we had recently moved to Winston-Salem, North Carolina, where my father had been called to serve on the staff of the First Presbyterian Church and to begin a new congregation in a community just out from town. The church had found us a house and furnished it, and we had frequent visits from members. On these occasions Mother would always serve a rather elaborate Chinese tea. The pièce de la résistance of these teas was her antique denshin box. It was a wooden box about fourteen inches square with nine beautiful porcelain interior sections. In each of the separate sections Mother would put a different treat—sunflower seeds, pumpkin seeds, watermelon seeds, sesame cookies, and peanuts. Usually small Western cookies or candies would complete the nine sections and keep the refreshments from seeming too exotic.

This picture appeared in the Winston-Salem Journal and Sentinel in the fall of 1941 when we had just moved there. The famous denshin box is on the table.

One particular afternoon I had decided to be helpful. The denshin box needed to be refilled. I carried it carefully to the kitchen and filled each lovely little section. Then, just as I started back toward the living room, the heavy kitchen door swung back, and the box and all its contents went crashing to the floor. Mother’s precious antique sections lay in several dozen pieces at my feet.

Before I could even start to cry, my mother was at the door. She didn’t even glance at the floor. She looked straight into my stricken face. “Are you all right, darling?” she asked. At that point I burst into tears, but she put her arm around me and told me not to worry. Daddy could probably glue the thing back together anyhow. I was nine, but I knew that day that as long as I lived I would remember that my mother had cared more about how her child felt than any cherished antique, and I resolved that if I ever had any children I would remember that scene. I must never forget that a child’s feelings are always more important than any possession.