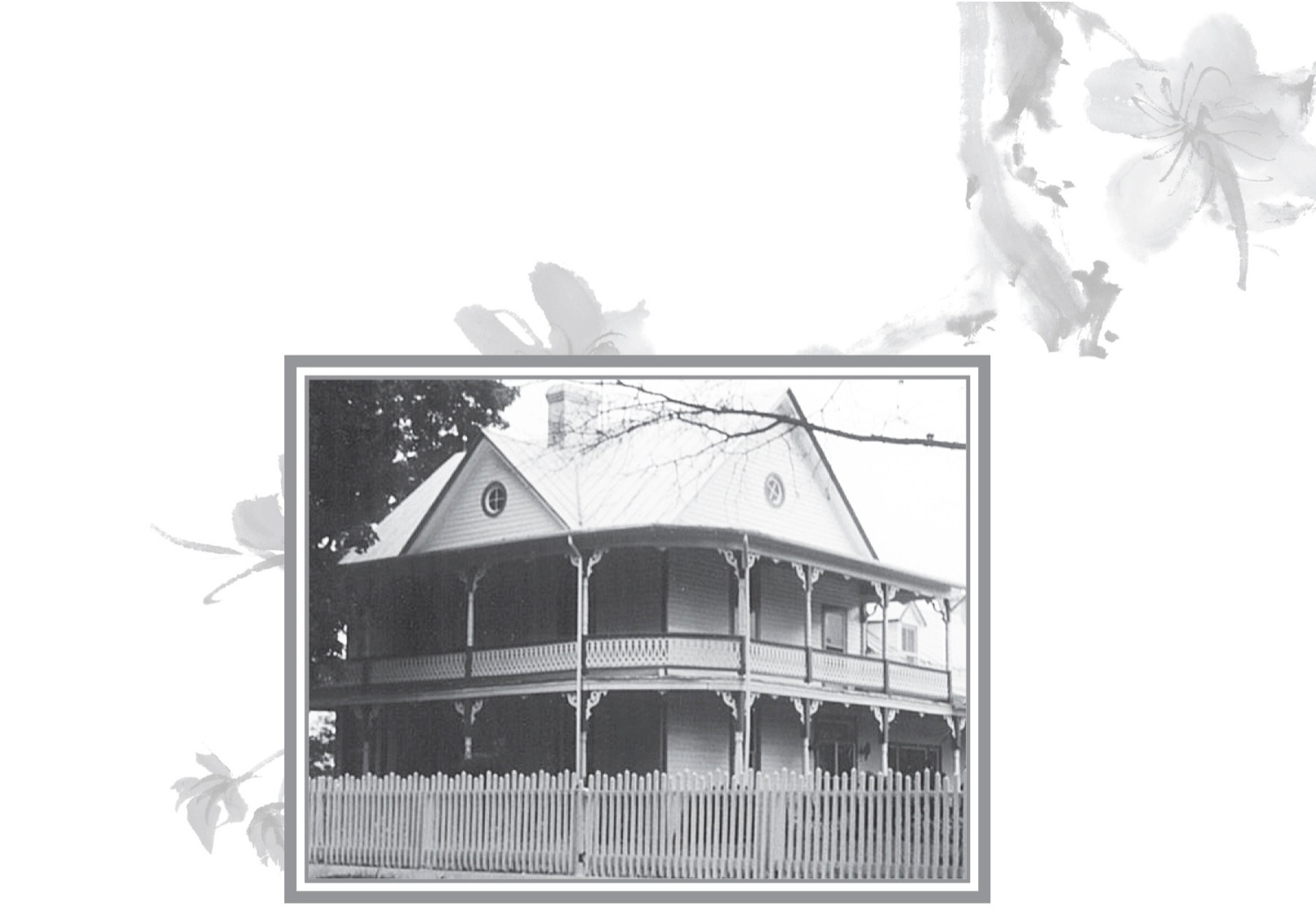

The Lexington farm house.

George Raymond Womeldorf

When we were reading submissions for the National Book Award, Julius Lester, who was also on the jury, said wistfully that he wished we could see at least one book that had a good father in it. Soon after that I began to write Preacher’s Boy because I knew what it meant to have a good father. Robbie’s father in the book is a minister who loves his children wisely and well. My minister father sprang from stern Calvinist roots, and I, being a whiney, attention-craving child, often disappointed him. But I know he loved his children every bit as much as Robbie’s father did, and one day when I was fourteen, I understood that fact in a way I never had before.

World War II ended the summer of 1945, and the following summer we prepared to return to China. My parents had spent nearly eighteen years as missionaries there, and my father, especially, could hardly wait to return. I think all of us were eager to go home at last. My father had given up his work in Winston-Salem. We suffered through all the needed shots, including the inoculation for black plague. We had made the rounds of the relatives to say good-bye for another seven years, when the word came down from the mission board that the inflation rate was through the roof in China and our departure would be delayed. We had no home to go back to, but someone lent us an unheated summer cottage in the mountains for a few months until an apartment in the complex for missionaries in Richmond, Virginia, opened up in the late fall.

My father was hardly ever there. The mission board had him traveling all over the South speaking in churches and to college groups about missions. The idea was that at any time the mission board would give us the go-ahead to go back to China. By now my brother Ray was in training to become a navy pilot and my sister Elizabeth was ready to go to college, so they would not be going with the family. But my two younger sisters, Helen and Anne, and I were scheduled to return with our parents.

There was a large desk in the Richmond apartment that was, quite naturally, my father’s workspace. In a big family it is important for individual privacy to be respected. We did not go into each other’s bureau drawers, much less into Daddy’s desk. But I was desperate for paper that I needed for a school project and went into his desk hoping to find some. What I found instead was an official-looking letter from the mission board. If I had no business going into his desk, I certainly had no right at all to read his mail, but the envelope had long ago been opened and I was curious. I pulled the letter out and read it. Several months before, the executive had written to say that given the current rate of inflation, sending Katherine to high school in Shanghai would be too expensive—that if my folks would leave me behind, they could return to China at any time.

I can still feel the tremor that went through my body. My father’s closest friends were Chinese, as well as the life’s work he believed God had called him to do. China was home and we longed to go home. We could not and it was all my fault. If it weren’t for me, my parents and younger sisters would be back in China already. Other missionary parents were leaving their children behind. In the apartment across the hall, Margaret, who was just my age, was going to be left with friends in Richmond while her parents returned to Korea.

I don’t know how many days it was before my father came back from his trip. It seemed like years. When he finally returned, I had to first confess that I had gone into his desk, worse, that I had read a letter addressed to him, and then I had to say that I knew why we hadn’t left for China yet. I somehow stumbled through all those confessions, and then I said, as bravely as I could manage, “I know how much you want to go. It’s all right if you go without me.”

Daddy looked at me with the most loving expression I had ever seen. “Sweet girlie,” he said, using his pet name for his four daughters. “Sweet girlie, we wouldn’t leave you behind.”

In the Book of Genesis, Abraham believes that God is commanding him to sacrifice his beloved son as proof of his love and obedience. But just as Abraham is about to thrust the knife into his terrified child, an angel grasps his hand and there in the thicket is a sheep that God has provided for the sacrifice. Most people find this story horrifying, but what my father taught me that day was this: No matter how sacred the calling appears, it is not God’s will for parents to sacrifice their children.

It is no secret that my books have often been attacked by Conservative Christians, people whose core theology would probably be quite close to my father’s. One such person, who was very critical of the language Gilly uses in The Great Gilly Hopkins, asked me testily, “What would your father think of such a book?” And I was happy to reply that of all my books published before his death, The Great Gilly Hopkins was his favorite. “Of course,” I added with a bit of the mischievous spirit I inherited from him, “my father had read Jesus’ parable of The Prodigal Son.”

George Raymond Womeldorf, whom I called Daddy until the day he died, claimed that the only whipping he ever got was in the Sunnyside one-room schoolhouse. It seems that every school day closed with the Lord’s Prayer and during the middle of the prayer one evening, the boy behind him hit him in the back, and Raymond (as he was always called at home, since his father was George) came out with a “strange noise.” The elderly teacher, Mr. Hall Lackey, whipped both boys but not, according to Daddy, very severely.

My father was born on a farm a few miles out of Lexington, Virginia, on September 7, 1893 (or 1894; the records disagree.) His parents were George William Womeldorf and Lillie Belle Clements. He started at Sunnyside School at the age of five with his older brother, William, and his two older sisters, Katherine and Mamie. Maude, Joshua, Herman, Cora Belle, and Florence came along in due time. He characterized himself as something of a runt who didn’t start growing until his early teens and was consequently able to slip along between the ends of the double desks and the wall and visit his friends without being seen by the teacher. There were five-year-olds and twenty-five-year-olds among the thirty-plus students, though the older boys only came to school when the weather was too bad to work on their family farms.

Except for the bullying of the small boys by the larger ones, he remembered his school days at Sunnyside as pleasant ones. Everyone had to work to keep the building going. The boys chopped wood and carried water, which was a coveted task, for the boys enjoyed the leisurely stroll to the spring. The girls, sometimes with help from the boys, swept the floor. He wondered how anyone learned anything at Sunnyside with all the different ages and stages of students. No grades were given, and the learning was a bit haphazard. This may help explain why my father was twenty when he enrolled in Washington and Lee University even though he started elementary school when he was not quite six.

At some point, Mr. Lackey retired and a Miss Ella Pultz took over. The lady was very strict and an excellent teacher. At some point she closed the building at Sunnyside and moved the school to her home, which was a three-mile trek each way from the Womeldorf farm, but Raymond recalled that “the deeper the snow, the better we liked it.”

When William and Katherine were old enough to leave Miss Pultz’s school, they began the seven-mile trek by foot over muddy roads to continue their education in the town of Lexington. After a year of this my grandfather decided that he needed to move closer to town. He had nine children and he wanted all of them to have a good education. It was then that he bought the farm one mile east of Lexington that I pictured as the setting for the farm in my book Park’s Quest. The stone part of the house dated to Revolutionary War times, but most of the house was frame, Victorian style, with a gabled round window in the attic that I called a cupola in the book. The old frame barns and fields were just as I described them there, and the springhouse, which plays such an important part in the plot, was my favorite place on the farm and is depicted exactly as I remember it. I knew that one day the farm would likely pass out of the family, so I thought I could keep it if I put it into a book. Indeed, after Daddy’s sisters Cora B. and Florence died, we had to sell the farm. We were sad to do so, but there were debts that had to be paid, and none of the next generation was going to be farming.

The farmhouse was on the side of a hill, and the spring that provided water and the springhouse that provided refrigeration were many feet below at the bottom of the hill. For every meal, the milk, butter, and buttermilk had to be carried up to the house and leftovers returned afterward. Water for drinking, cooking, washing, and bathing also had to be carried up the hill. It was a great day in the Womeldorf household when their forward-thinking father bought a ram, an invention that, using gravity, pumped water up to the house. The farm seems to have been a wonderful place to grow up. There were sleigh rides in the winter and, in the summer, so many peaches that they left the farm by the wagonload. And what didn’t go out by wagon was peddled by the children. One of my favorite memories of the farm was the hand-cranked ice cream using the rich cream from the cows, and peaches from the orchard. The milk was so rich, in fact, that it caused my grandmother’s butter to lose a blue ribbon at the fair. The judges thought she must have added coloring to make it that yellow. My Calvinist grandmother was incensed to have her integrity so impugned.

My father’s high school years were spent at the Ann Smith Academy, where the principal was a scholarly gentleman by the name of Harrington Waddell, whom my father greatly admired. This was despite the fact that Mr. Waddell gave him his only demerit. It seems a certain Billy Cox, who sat behind him in class, had stuck a needle between the sole and upper part of his shoe, and he used his homemade weapon to give Raymond a jab in his nether regions. Raymond jumped to his feet ready to give Billy a blow to the jaw when Mr. Waddell walked into the classroom.

There had been four Williams in his older brother’s high school class, so all of them took the names of Caesar’s generals. His brother was dubbed Titus Labienus, shortened to Labby, a nickname my father inherited when he entered the academy and which followed him through college and into the army. No other memories of high school seemed quite as vivid as the case of the lone demerit, but he did recall being in both the junior and senior class plays and was the salutatorian at graduation.

My grandparents were hardworking and devoted Presbyterians. Grandfather was an elder, and church services and Sunday school were a big part of every Sunday. They traveled by horse and buggy to the old Timber Ridge Presbyterian Church. Even after they moved closer to town, they continued to drive the eight miles back through every kind of weather. I’m not sure when they moved their membership to the church in town, but I think it was before my father left the farm for World War I.

Some of my father’s earliest memories were of gathering around the piano in the parlor and singing hymns while his mother played on one of the first pianos in the area. After supper every night there were evening prayers, which consisted of Bible readings—beginning at Genesis, a chapter a night until the end of Revelation. As each of the nine children learned to read, he or she was expected to read a verse. Then they all got down on their knees while their papa prayed. This custom continued until Cora B. and Florence, the last family members, were in their nineties and unable to kneel. We grandchildren spent a lot of time on our knees trying not to giggle.

Being strong Presbyterians, every child was expected to learn both the Child’s Catechism and the Westminster Shorter Catechism. So after Sunday dinner dishes were washed, the children got down to memorizing. The denomination awarded New Testaments for memorizing the Child’s Catechism and Bibles for the Shorter Catechism. It didn’t matter that the latter was written by the Westminster Divines in England in 1640 and adopted by the Church of Scotland in 1648; every properly brought up Presbyterian child could repeat its questions and answers by heart.

The catechism tradition lived on after my grandparents’ deaths. I got my Bible in 1941, as my aunt Katherine, who was known as the champion catechism teacher in the Lexington Presbytery, was determined that her namesake be the youngest pupil she had ever coached to receive the coveted Bible. She had me follow her around the hen house while we gathered eggs. She knew all the questions by heart, of course, so she would call out: “What is God?” To which I had to immediately reply: “God is a Spirit, infinite, eternal, and unchangeable, in his being, wisdom, power, holiness, justice, goodness and truth.” Or “What is sin?” To which I would cry over the clucks of the hens: “Sin is any want of conformity unto or transgression of the law of God.” Neither my father nor I remembered catechism sessions as unpleasant or taxing and we were both inordinately proud of our Bibles. I still have mine with Katherine Clements Womeldorf embossed in gold on the worn leather cover.

The Womeldorf family loved music, and one of Daddy’s happiest memories was of the day his father came home from town bearing a morning glory horn Edison phonograph with round cylinder records. “How on earth could that contraption sing and play lovely music?” he remembered marveling. The family considered it the wonder of the age and loved listening to it.

My father entered Washington and Lee University in the fall of 1913, walking the two miles from the farm every day. I once asked my father why he didn’t ride a horse to school during his four years there. “I’d have to fool with the horse once I got there,” he said. “It was easier just to walk.” Once he took us to W and L, where we paid respects to General Lee’s recumbent statue in the chapel and to the skeleton of his horse, Traveller, in the museum. My father told us that when he was in school, the skeleton of the famous horse was in the biology lab along with a skeleton of a colt. He related with great glee how student tour guides taking visitors through the buildings and grounds would point out Traveller’s bones, and, then, when they got to the smaller remains, would add, “And this is Traveller as a colt.” Many visitors seemed to accept this, much to the delight of the students.

While the actual Traveller bones were in the biology lab, on a day when the professor was late, the boys decided to autograph the skeleton. The ink was washed off soon afterward and the skeleton removed to the museum, but my father had signed the inside of a rib and that day we visited, he grinned mischievously and pointed out his unmistakable scrawled signature.

He entered the university the fall of 1913, and World War I began in Europe the summer after his freshman year. In 1917, at the end of his senior year, he joined the W and L ambulance corps. Training took place in Allentown, Pennsylvania. Raymond, who had never driven a car before, was placed behind the wheel of a Model T ambulance and told to drive it between two stakes. “I thought,” he said, “that the point was not to knock down the stakes, so I didn’t.” By so doing, he had unwittingly passed his driver’s test. He did plenty of marching after that day, but that single maneuver through the stakes proved to be the end of his driver education course. The next time he found himself behind the wheel was on the outskirts of Paris. “I wished many times during that drive across Paris that I’d had the sense to knock down those stakes.”