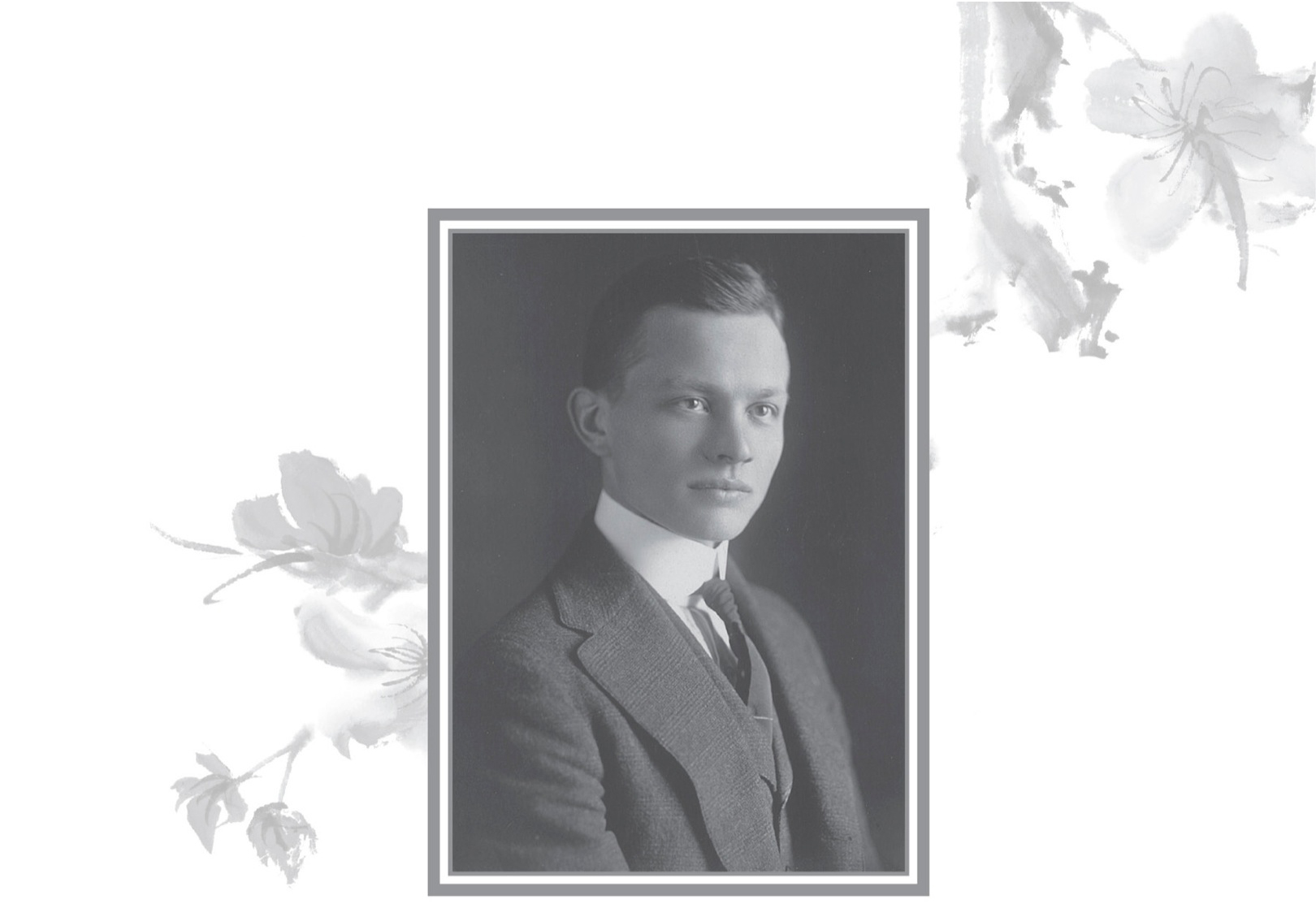

G. Raymond Womeldorf’s college picture.

Over There

Although my father died many years ago, a vivid reminder of his ambulance days recently arrived in a large box on my front porch. Inside was an old leather medical bag. It had come from the son of my college professor G. Parker Winship. David wrote that he had found the bag in a shop in Abingdon, Virginia, noted the unusual name, and sent it to me thinking I might know to whom it belonged. On the side in indelible ink was printed: R. G. Womeldorf, Lexington, Va, USA. The recruiter in 1917 had mistakenly listed my father as Raymond G. Womeldorf rather than G. Raymond—an error that caused a lot of headaches when my father applied for veteran’s benefits under his correct name. What David had sent me was obviously my father’s World War I medical bag. It is now in the collection at Washington and Lee.

My father never talked much about his time at the front, but I once got a glimpse of what it felt like to him. He was visiting us and we turned on Masterpiece Theater to watch Upstairs, Downstairs, a series to which we were somewhat addicted. The son of the household had gone to war and as the scenes of the trenches of World War I began to play on the small screen, my father stood up abruptly and left the room. I followed him out. “Is this hard for you to watch?” I asked. “Yep.” It was all he said.

The Washington and Lee Ambulance Corps, also known as Section 534, landed in France on February 4, 1918. It was a month before they met the twenty adapted Model T Fords they were to drive. My father took #13 because no one else would. That next couple of weeks were spent learning how to take the engines of their “Tin Lizzies” apart and put them back together. Then the section drove from Paris to the grounds of the Palace of Versailles. The great fountains were all sandbagged; still, King Louis’ palace was quite impressive to a farm boy from Virginia.

They were to be attached to the 12th French Army that had been so decimated in earlier battles that they had been withdrawn to recruit and regroup before they were once again called into action. In the meantime the 534 was ordered on March 25, 1918, to head for the front to transport wounded French soldiers from the battle of Somme. They could hardly move their vehicles forward for the stream of men, women, and children jamming the roads, desperately trying to flee the slaughter.

The job of the 534 was to evacuate stretcher cases from the dressing stations near the front to hospitals that were often simply cathedrals or warehouses. They spent two weeks doing this, never having time even to take off their clothes, much less rest. When at last they were relieved for R & R, they stopped by the US headquarters in Chaumont, where the officer in charge threatened to throw them in the brig for wearing soiled uniforms, failing to shave, and having mud on their boots. My father mused that the newly arrived Americans had never seen men from the front before. But had they known their presence would receive that kind of welcome, they would never have stopped there.

We children were brought up in a teetotaler household, but it occurred to my brother that our father might not have always been abstemious. “Daddy,” he said, “when you were attached to the French army did you ever drink wine?” My father looked at him in amazement. “You don’t think I would have drunk water, do you? It would have killed me.”

William Roth, a teacher from Wisconsin who had been added to the W and L unit, wrote a memoir of the 534. In it he recalls an occasion when he and Labby Womeldorf went to a water fountain near the camp kitchen only to find a notice reading “eau non-potable.” They filled their canteens with the dry red issue wine and, because they were so thirsty, gulped it down. Since neither of them was used to alcohol they could only make it back to their billets by holding on to the buildings along the way.

Once the two of them visited an old invalid who had been a dancer and entertainer. They took a morning glory phonograph and cylindrical records they had salvaged in the Somme and played them for the old man, who sat up in bed and beat time to the music with his arms. Around this same time they helped an elderly couple they had met by hauling in their hay and were rewarded with a lunch of bread, cheese, and wine.

Months after that Roth tells of a walk he and Labby were taking when they came upon an enormous unexploded shell with German markings on it. “Let’s end it up and take our pictures beside it,” said my father. While two French soldiers nearby shook their fingers and yelled “Non! Non! Non!” the crazy Americans, after a couple of tries, were able to upend the heavy shell. It stood shoulder high and, Roth guesses, weighed over a thousand pounds. Roth and Labby each took a picture of the other holding up the shell. When it didn’t explode, the French soldiers came running over to have their pictures taken, but Labby shook his index finger and said “Non! Non! Non!” and tipped the shell back onto to the ground.

“It seemed,” says Roth, “that Labby liked to take risks. During the Marne-Aisne Offensive he gave me a demonstration on how to explode the detonating caps of German hand grenades (potato mashers). Also he liked to toss pennies on condition that restitution was made after the games. In the dud episode there would have been no restitution if we had lost.” I knew my father harbored more than a streak of mischievousness, but I was somewhat taken aback by his obvious daredevil nature as a young man. When I read what William Roth had written, I sighed. So that was where my own two boys had gotten the trait that was turning their mother’s hair gray.

But very little of those long months in France was given over to fun and games.

Here are parts of a letter he wrote to his brother William on the 28th of July 1918 after the second battle of the Marne.

Dear Brother and all,

As we have been on the go for over a week there has not been much time for writing. But as I don’t expect to be called out tonight I am taking the time to write a short note. Perhaps you may be able to read it as I am in my bus along the road writing on a cushion on my lap by candlelight.

We are getting along fine and are again as busy as at first. But are on a front that is moving in the other direction above the old chateau that has made quite a bit of American history of late. We have been going day and night for four days now. But the work is much better at least it seems so when things are favorable. The Americans that were on this front did some excellent work and not only manned their artillery but when they captured a lot of German artillery, just turned the guns around and fired them, also as much ammunition was also captured. That was quite a stunt and has been practiced by others since.

We have seen many prisoners taken and have hauled quite a number of wounded Boche.

I have changed my mind about the quiet night, because they have commenced to go both ways as thick as hops. Perhaps more work tonight.

The souvenir gatherers should be here. They could find anything from a Boche tank to cartridges and the like. I have seen so many helmets, etc., that I would like to get to a place where there are no souvenirs. You have seen the pictures of the forests, how they are torn and ruined; well those are no exaggerations. I saw this afternoon one tree between three and four feet in diameter cut off. And the smaller trees are lying in a tangled heap everywhere. Now and then there will be a shell that did not explode in a tree, while some of the trees are so full of shrapnel and bullets that they are well loaded.

We are well. Our headquarters are in a small town where it was impossible to find enough of good roof left to keep the cooking stove dry. So you see we must sleep in our cars or in dugouts, which are very damp, especially after several rainy days that we have had. Such is life in a place that wherever you and your “Lizzy” keep together you are at home. You never worry about getting back, you are always there. . . .

The wheat, what is left, is very fine indeed, if it could be harvested.

Censored by 1st Lt. A.A.S. Your brother,

Raymond

P.S. How does that Overland run now? Ride over and I will race you in my Ford. I know you all enjoy it very much. R.W.

Roth’s memoir includes many details of the 534. Of the dangers they regularly underwent, of the seemingly useless taking, losing, and retaking of decimated villages, of the night drives on rutted roads with no lights burning, and the wasted countryside. In my father’s own brief memoir, which he wrote for us children, he says: “It is useless to speak of the horrible slaughter of these fronts.”

One of the novels that was hardest for me to write had to deal with the horrible slaughter of war. I almost didn’t finish Rebels of the Heavenly Kingdom for just that reason. When I hear men bragging about their war experiences I wonder just how much they actually witnessed. The people I have known who, like my father, were in the thick of the horror rarely spoke of it. I finished writing Rebels in 1982 and took the manuscript to my father for him to read, but he shook his head and said he’d rather wait for the book. He died a few months before it was published. So I wasn’t to know how he would react to the terrible scenes of war that I had imagined but he had lived through.

With fall the section moved up into Belgium, and it was here, on October 31, that my father, who was waiting to take the wounded from a dressing station in Wantgren, was hit in the leg by a shell fragment. Soon afterward the area was gassed, and he pulled off his gas mask in a frantic effort to cover his wound. He knew that if gas got into it, it would soon become gangrenous. In telling of the incident, Roth says: “He was an excellent and fearless driver.” When I learned as an adult that my father had been wounded on the day that was to become my birthday, I wondered how he might think of that anniversary. He never mentioned the coincidence. Perhaps he didn’t want to remember that day in 1918, or maybe he remembered and didn’t want to spoil my birthday by speaking of it.

Womeldorf family. My father is the tall one in the back row.

Dad before being wounded.

Raymond was taken to a French hospital, which was an old cathedral, where he lay for two weeks. He remembers lying there, unable to speak or move and hearing the doctor who was leaning over him say: “You can forget this one. He’s gone already.” So he strained every muscle in his body to move something to show the doctor that he was still alive and managed to wiggle a toe.

He and others were shipped to an American hospital, only to find that it was not there. So they simply lay on their stretchers in tents for days until they were finally sent on by freight car to a casino in Boulogne, France, where it was necessary to amputate his right leg just below the knee. His earlier attempt to save his leg had failed and only resulted in damage to his lungs.

On a post card provided by the French army, he wrote:

My dear father and mother and all. I am getting along as well as could be expected. Now don’t be all worried and stirred up.

Your devoted son,

Raymond