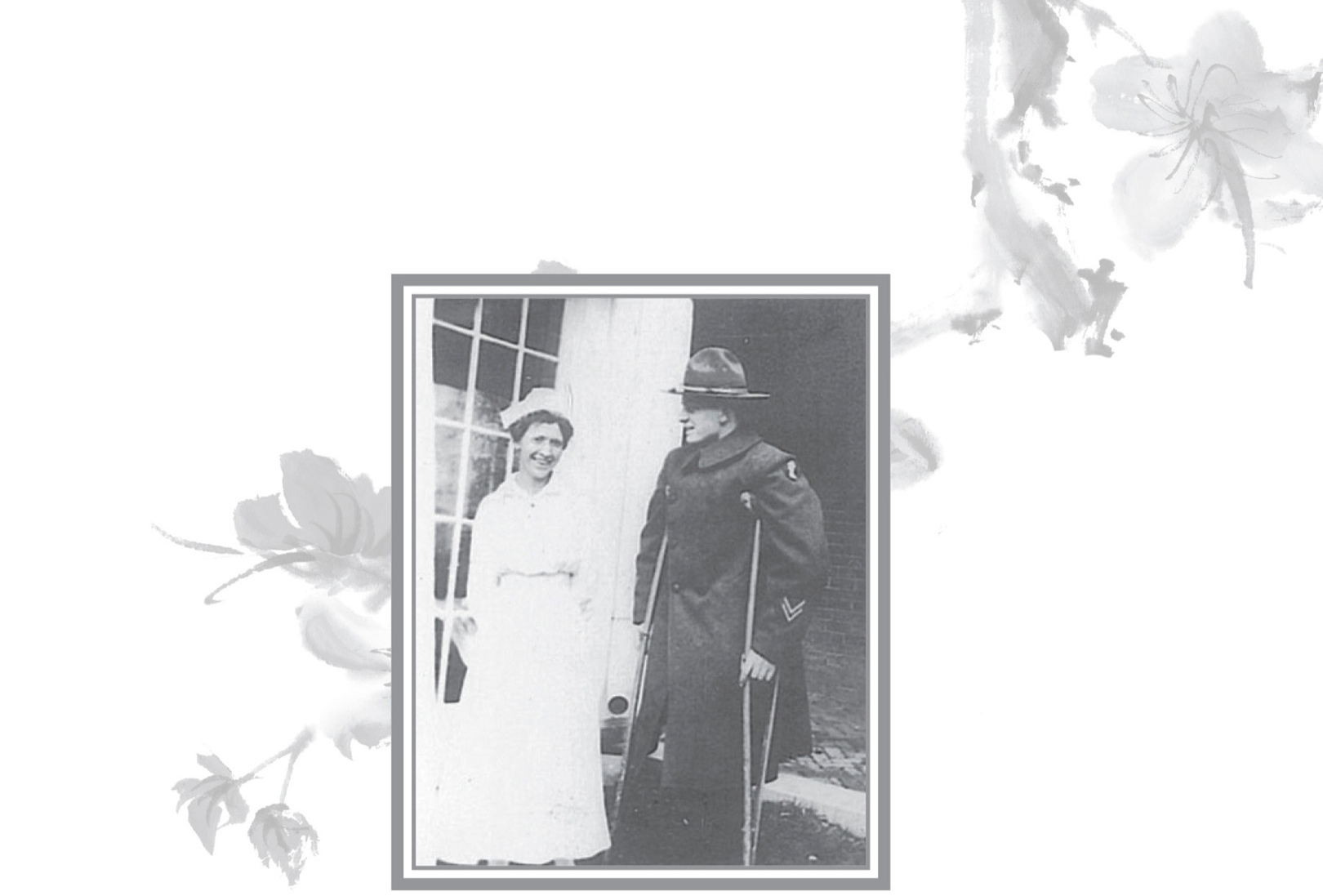

Dad at the hospital.

In Hospitals

Finally, after weeks of recovery in the casino, my father found he could sit up and see across the channel to the White Cliffs of Dover. At Christmastime the nurse brought him a gift of fruit that she said a kind person in Virginia had sent the money for, hoping it could be given to some wounded soldier from Virginia. The donor turned out to be one of his high school teachers. He always cherished this happy coincidence.

“Well,” he wrote home, “I’m getting along all right; of course it is a slow process. You should see my rosy cheeks. Every day the sun shines four fellows pick up my bed and carry me out on the veranda. Yesterday I was out in time for a band concert. Everyone is as nice to me as possible. My nurses brought one day steak and mushrooms, another chicken and often fruit from their own mess.”

At length he was sent to England, where he was in hospitals in Dartforth and Liverpool before finally being shipped back to the United States and to a hospital in New Jersey.

I think it was while he was at that hospital that he decided to try to visit New York City. He hadn’t yet been fitted with an artificial leg, so he was painfully trying to make his way on crutches when a limousine pulled up to the curb beside him and a plump, middle-aged woman with a heavy German accent leaned out and asked him where he was going and if he would like to have a ride. He gratefully accepted and climbed into the backseat beside her. The kind lady proved to be the Austrian opera singer Ernestine Schumann-Heink, who had had sons fighting both for Germany and the Allies during the war.

Several years later when Raymond was in seminary, Madame Schumann-Heink came to Richmond to give a concert. He had no illusions that the famous contralto would remember the ride in New York, but he was eager to see her again. So he went to the concert, and afterward, stood at the back of the formally attired stage door crowd to get a closer glimpse of her. Suddenly, he heard a cry: “My son! My son!” and she made her way through the surrounding fans to give him a warm embrace. It was my mother who told me the story, regretting as she did that he hadn’t taken her to the concert.

After his stay in New Jersey, he was transferred to Walter Reed Hospital in Washington, DC. Here he met another noted woman, one who may have saved his life. She was Mrs. Lathrop Brown, whose husband had been special assistant in the Department of the Interior and was currently high up in the Wilson administration. People in the Interior department gave a small portion of their salaries each week to support a convalescent home that was run by Mrs. Brown and a nurse. Mrs. Brown had been a New York debutante, her husband had been Franklin Roosevelt’s roommate at Harvard. Needless to say, the eleven fortunate veterans whom she selected for residency received extraordinary treatment. In the summer, she even took her invalids to the Browns’ summer place on Long Island for fresh sea air. My mother always believed that left in the crowded wards of Walter Reed, my father would have died. Raymond was under Mrs. Brown’s care for several months, living, in his words, “the life of Riley.” By the end of October, however, the doctors feared that the gassing may have given him tuberculosis. He needed, they felt, to be isolated and treated for TB.

The friendship with Mrs. Brown did not end when he had to leave the Interior Department’s Convalescent Home. She remained in touch with my parents until her death. Every year she would send to us in China a carton of wonderful children’s books, a great treasure for a family living “up country” who had no way to purchase books in English even if they’d had the money. She often wrote and even came to China once to visit us. If we were to designate a fairy godmother of our childhood, it would be this gracious lady who saved our father’s life and enriched us all. In 1938 when we arrived in New York as refugees, Mrs. Brown was on a trip to Europe, but she had arranged for her chauffeur to meet us at the boat. We must have received our share of startled looks from the crew and other passengers—this seven-member family emerging from their third-class lower deck and climbing into a waiting chauffeur-driven limousine.

After Raymond’s time in the convalescent home, there followed a couple of TB hospitals—one in Connecticut and one in the Adirondacks. The current treatment for TB patients was quite literally fresh air—the colder the better. So my Virginia father found himself at a Saranac Lake “cure cottage,” where the patients were rolled out on the porch to breathe in the mountain winter air for most of the day. He had lived through gangrene, amputation, and gassing, but now he thought he would surely freeze to death. Among the patients was another veteran from Virginia—a graduate of the University of Virginia. This man realized that illiterate veterans were being taken indoors for an hour or so every day for reading lessons. He proposed that the two of them feign illiteracy and gain a welcome break from the cold.

The ruse worked, at least for a while. Then to Raymond’s disgust, his friend whispered something to him that made the instructor look more closely at the two of them. “Have you boys ever been to elementary school?” she asked. They nodded. “Have you had any high school?” They nodded again, this time a bit sheepishly, for the teacher was obviously annoyed. “How much education have you had?” she demanded furiously. And when they admitted that they were both university graduates, she immediately called for an attendant to wheel their beds out and force them to face the elements.

By summer, when it was finally determined that, though his lungs were indeed damaged, he was not suffering from TB, he was at last allowed to go home. He had applied and been accepted at Princeton Theological Seminary while he was still hospitalized, but when he told the pastor of the Lexington church this, Dr. Young persuaded him to cancel these plans. In those days the Presbyterian Church was divided as it had been since the Civil War. If, Dr. Young said, he expected to work in the Southern Presbyterian Church, it would be a mistake to go to a northern seminary. Dr. Young took charge, canceled the Princeton registration, and made sure Union Theological Seminary in Richmond, Virginia, would accept his late application. So we children must be thankful to the imperious Dr. Young for making it possible for our parents to meet and our subsequent births.

As I write this I remember a similar event in my own life. While in Japan I was notified of a scholarship for further study that I could use where I wished. I applied to Yale Divinity School, where two of my favorite professors had received their doctorates and was accepted. In the late spring I went to a meeting in Tokyo and an American missionary acquaintance asked me what my plans were for my year in the States. I told him I had been accepted at Yale. “You don’t want to go to Yale,” he said. “You want to go to Union Seminary in New York City. That’s where the exciting things in Christian Education are happening.” I protested that it was too late to apply, but he assured me it was not, and with his help I changed my plans. If I hadn’t, I would never have become Katherine Paterson.