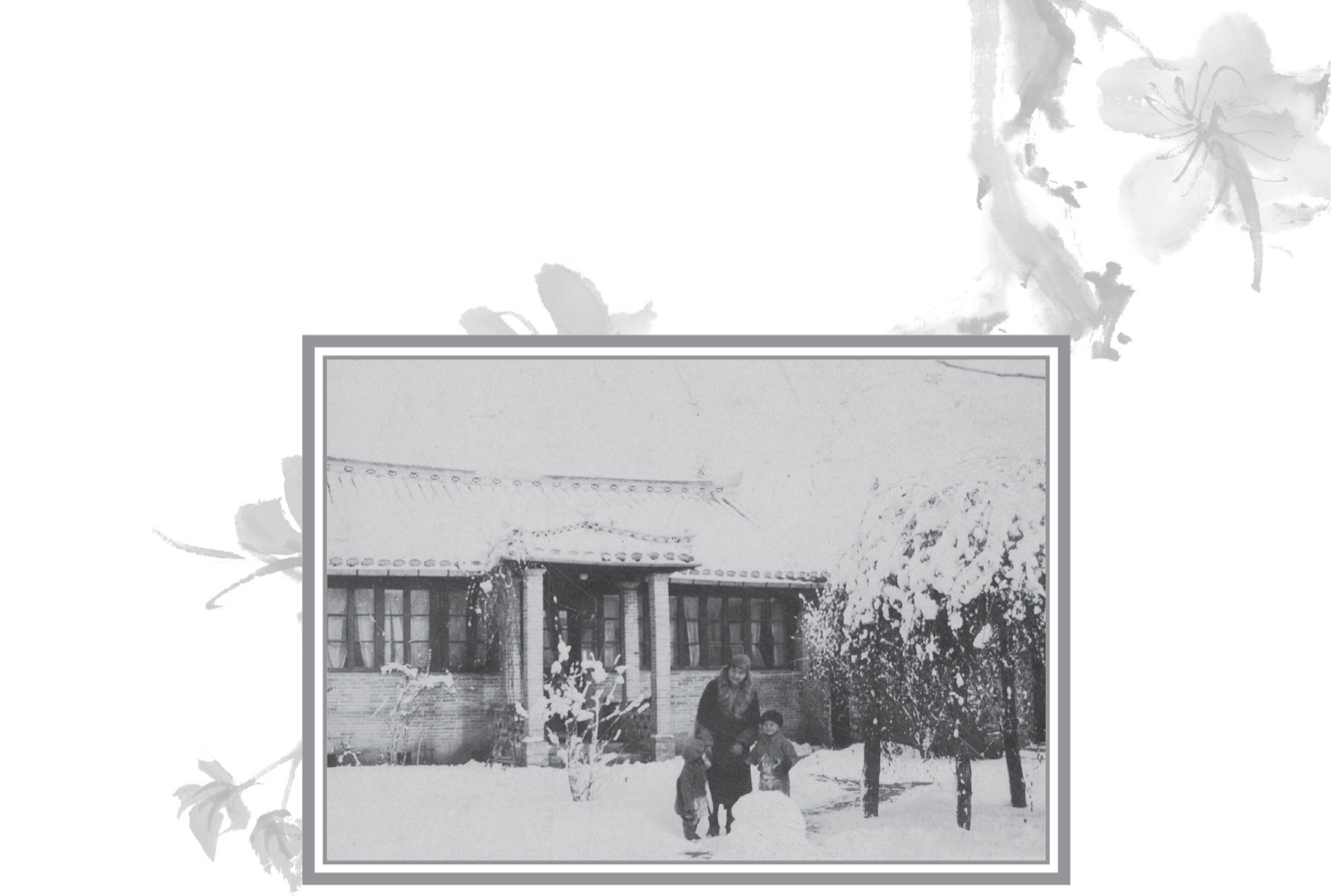

Liz, Mother, and Ray. Our Huai’an house.

Enemy at the Gate

Huai’an was home, and in some ways until I’d lived for many years in the same house in Vermont, Huai’an would always be what I thought of as home. And yet, I wasn’t quite five years old the last time I saw the courtyard with its moon gate or ran down to Mrs. Liu’s house for lunch. There had been rumblings of war with Japan for quite some time, but it broke out in earnest in July of 1937. Our family of seven had gone to the mountain resort then known as Kuling for a few weeks’ respite from the brutal heat and humidity of a Hua’an summer. The president of China, Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, and Madam Chiang were also vacationing there when we arrived. I was told that we met the first lady on a walk one day, and she patted my sister Elizabeth and me on the head and admired our blond curls. But soon thereafter, the general and his retinue left the mountain. The Japanese had invaded North China. We were at war.

Before the month ended, the Japanese had landed at Shanghai. We could not go home. Three weeks later, my sister Anne was born. The mission decided that the men and single women could return to their mission stations, but the women with children must stay on in Kuling until the situation quieted down. It was a terrible time. Bombers flew over our house nightly while we sat in dark rooms with all the curtains closed, wondering where those bombs would fall. We waited for word every day from our father, never knowing if he was safe or when he might return. I could only imagine how my mother must have suffered with a baby, a toddler, and three children five, seven, and ten who were old enough to be terrified but not, I’m afraid, much help to her.

My father told one remarkable story about that fall he spent in Huai’an. The Japanese army was fast approaching. He had heard stories of the atrocities the invaders had committed elsewhere, so he gathered as many women and children into our small compound as he possibly could, hoping somehow to protect them, though he feared it would be impossible.

I’m sure he could tell from the sounds on the street outside that the army had entered the massive gates of the city. Eventually, there was a knock on the wooden gate of our compound. The gateman asked who it was and was told it was the Japanese commander, who wanted to be let in to speak to the reverend.

The commander came in alone, as I recall the story, and handed my father his card. Then he said in English, “I know you are a Christian. I am a Christian too. I am not sure I can control my men. But if anyone tries to break down this gate tonight, you must send someone over the wall to find me. I will come and try to stop their entering your compound.”

That night there was pounding on the gate. My father got a boy, perhaps the son of the gateman, I don’t know, handed him the card, and sent him to find the commander. The commander came. He ordered his men to leave the area, and, miraculously, they obeyed.

The infamous “Rape of Nanking” that occurred not long afterward, just 102 miles farther north, tells a story of what might have happened at my childhood home were it not for that commander.