Article in Episcopal magazine about Maud Henderson.

Courtesy of the Archives of the Episcopal Church, USA.

Maud Truxton Henderson

During the time we lived in Charles Town, West Virginia, we had a visit from an old friend from China days. Her name was Maud Henderson. Maud had spent most of her life saving those Chinese baby girls that their society had too often regarded as disposable. Mother told me the story of how she had stood at the gate of her compound and told the Japanese soldiers there that if they tried to come in and get her girls, they would have to do it across her dead body. This story alone made her one of my childhood heroes. Maud felt particularly close to my parents because she and my father both came from Lexington, Virginia, though they only met when we were in Shanghai. The last time we had seen her was just before we left China in 1940.

When she came to visit us in Charles Town, West Virginia, nine years later, her round face was as wrinkled as a dried apple and she was almost toothless. Her hair, peeking out from under her deaconess headdress, was white, and when she took off the headdress it barely covered her pink scalp.There are two things she said that I have remembered all my life. One was said as she was smacking her lips over some particularly delicious dessert my mother had made: “I’ve only got one tooth left, but it’s all right. The dentist says it’s my sweet one.” The other: “I was the last person Robert E. Lee kissed before he died, and now I have kissed you.”

There is, of course, a lifetime between that second sentence and the first, and although the last time I saw Maud she was eighty and I was sixteen, it is now that I am over eighty myself that I have been able to fill in those long decades between. As I mentioned earlier, Kate DiCamillo was fascinated by the story of the famous kiss and told me if I didn’t write about Maud, she would. But Maud was my hero, so I set about to find out more than the little I could remember from knowing her and hearing my parents talk about her. To my amazed delight, I found that her niece had donated many of her letters from China to the University of North Carolina and that there were a few letters from and about her in the Archives of the Episcopal Church. So over the course of a couple of years, I gave myself the task of putting together her life story. It’s not part of my family history, but it touches it, first in Lexington, then Charles Town and Winchester (where my parents lived for thirty years), and, most importantly, in China.

Maud was born in Lexington, Virginia, on the 4th of December in 1868—three and a half years after Appomattox, the daughter of Mary and Francis William Henderson. She had, in the words of the Psalmist, a goodly heritage. Her father’s two given names came from his two godfathers, Francis Scott Key (who wrote our national anthem) and Episcopal Bishop William Meade of the Virginia diocese and the son of one of Washington’s aides. Francis Henderson was commissioned an officer in the US Army when Polk was president and was appointed the first postmaster in San Francisco. In 1861, he left the US Army and became a captain in the Confederate army, and, although he was a lawyer by the time Maud was born, he was always called “Captain Henderson.”

The Hendersons were a military family. Francis Henderson’s father was an army surgeon who, reportedly, made his rounds with his cat sitting on the pummel of his saddle. On the anniversary of his death, his widow told the family that she had something to do. She arranged her treasured articles, putting the names of each person who was to receive each item with the item, and then, in Maud’s words, “fell asleep and did not wake this side.”

The young Maud became too well acquainted with those who did not “wake this side.” It began with her mother’s death when Maud was a year and a half old. She had a remarkable memory. She remembered her father carrying her in to see her mother, hoping his wife would rouse enough to see her only living child. Her mother opened her eyes, Maud recalled. She was to die on Midsummer’s Eve.

Maud also remembered, or perhaps was told of, a sweltering Sunday later that summer when she was sitting beside her father in the church pew. After she had marched animal crackers up and down the prayer book, she settled in for a morning nap. Later, on the porch at the home of their friends the Lees, it was revealed that Maud was not the only napper that morning. She was occupying her accustomed spot on the general’s lap when he asked her, “What do you think of a daughter who pokes her father in the ribs with her elbow when he is nodding his approval of the preacher’s sermon?”

The storied Southern general was a close friend of her father’s and made a particular pet of little Maud. Traveller, the horse who had carried Lee through the war, provided her first horseback ride. Then at the end of September 1870 came the evening of the famous kiss. Her father and the general had attended the vestry meeting together at the Episcopal church and Maud had been left in the care of Mrs. Lee and their daughter, Mildred. When the men returned, the general carried Maud through the kitchen and took a cookie from the jar that stood in the pantry to give to Maud. Then he kissed her and handed her over to her father. She did not remember—but knew from being told—that her father was summoned not long afterward to the Lees’ home. After the general had bade Maud and her father good-bye, he went into the dining room, where his family and supper were waiting. He sat down, but as he began the grace, his voice faltered and he slumped over the table, paralyzed by a massive stroke. He died two weeks later. Mrs. Lee told Captain Henderson that little Maud must be told that while others had kissed the general after that, Maud was the last one he kissed.

She remembered being taken to see the general as he lay in state in the chapel of Washington College, of which he had been president since the end of the war. She thought how impressive her friend looked in his gray full dress uniform and wondered why he would not wake and take her up in his arms as he always did. Some years later, with no prompting, she pointed out to Mildred Lee just where the cookie jar had stood on that long-ago evening.

So there were two great losses in Maud’s life before she turned two, but the next four years were happy ones. Her father was her constant companion and people remarked how droll they looked strolling about the Virginia Military Institute campus—the tall captain and his tiny lady, “the slowest couple on the quad.” There weren’t other children in her life, but she didn’t feel the lack of them. The adults who were her neighbors doted on her, one even supplying a Christmas Eve Santa who, Maud always believed, had actually come down the chimney. Her cats, Moses, Aaron, and Jim, were her playmates, though she admits much later that they should have been addressed as Mrs. Moses, Mrs. Aaron, and Mrs. Jim. Jim was the favorite. She and Jim played endless games of hide-and-seek and at night Jim would sleep on Maud’s bed.

Then at nearly six, she was taken away from her beloved home and father in Lexington and sent to Charles Town, West Virginia, to stay with relatives. She was given no explanation for this move. It might have been an economic one, for while she was gone, the family home was rented out. Maud herself looked back on the years between 1874 and 1882 as her years of exile. From the time she was nine until she was thirteen and a half she was enrolled in the Episcopal Female Institute in Winchester, Virginia, eighteen miles to the east of Charles Town.

There is very little record of those years. I’ve only found two stories from them. One was that she asked to be confirmed by the Bishop of Virginia soon after the move, already planning at the age of nine to tell children in China about Jesus. Then there is in her later letters an extended account of an experience from the summer she was thirteen.

“Just before I went to Lexington in June, a friend living at Harpers Ferry was married and I was somehow included in the picnic for wedding guests and spent the day on Loudon Heights. I suppose we had something besides view, you can take that for granted, but my memory is the view, such a wonderful one, on a perfect day. The crowd started downhill and I stood looking drinking it in. They called me, I answered and stood looking down the Potomac, across the fields, and off in the far distant shimmering line which they said was Chesapeake Bay. As I stood I had a Psychic. It was as if a clear promise was given me ‘nothing will ever take it away, it is yours.’ And it has been my joy and refreshing through so many viewless days, or when no view would have been welcome.”

Her return to Lexington by coach was a joyful one. Her father warned her that all the cats but one had long ago disappeared, as the renters had disliked cats. Jim had been spotted in the neighborhood from time to time, but she was now a feral cat, and no one dared approach her.

Maud jumped out of the coach almost before it reached her front door and stood at the gate taking in the old familiar sights. Under the neighbors’ house she spied a cat. She was sure it was Jim. Maud called to her. The cat stood still for a minute, listening, then she bounded through the lilac bush, across the grass, and jumped up on Maud’s shoulder. As they entered the house, Jim ran ahead and leaped onto Maud’s old bed, curling up contentedly as she had in the old days.

Maud was obviously a bright and vivacious young woman. She bragged years later that she had once led the ball at the Virginia Military Institute, but she remained coy about the cadet who had invited her.

Two years after Maud’s happy return to the home she loved, her father remarried. His new wife was Maria Eliza Hamilton, the great-granddaughter of Alexander Hamilton, one of our nation’s founding fathers. Maria was from Maud’s account a wonderful stepmother to her husband’s teenaged daughter. She was a highly educated woman and was happy to share her learning and the books she loved with her eager pupil. Then when Maud was seventeen, Maria gave Maud the gift she had always wanted, a sister. Maud felt as though she was a second mother to little Louise, especially since the baby’s own mother was frail after the birth. Maria died when Louise was not quite a year old and Maud was eighteen. Meantime, Francis Henderson had become gravely ill.

On the last day of his life, he was too weak to hold Louise in his arms, but he asked Maud to bring the baby in to see him. “Oh,” he said. “I had so looked forward to her walking.” Maud carried her thirteen-month-old sister a few steps away and put her down on her feet. “Walk to Daddy,” Maud said, and the baby threw out her arms and took the few steps across the space to her father’s chair.

“Have I told you about that wonderful last evening?” Maud asked in a birthday letter to the grown Louise. “He was in coma and they wanted me to leave his bedside, but I would not . . . He became conscious of my presence and called the old pet name, Dear Little Heart.” And then, “Just at the last minute his face was transformed with life and joy, and as he passed over to the other side he rapturously called: ‘Mary, my mother, my Redeemer,’” as though, Maud thought, he was greeting Maud’s mother, his own mother, and Jesus as he woke on the other side.

Although Maud was almost nineteen and had been caring for her sister since the child was born, on the death of her father, Maria’s family came to claim the baby and take her to live with them in South Carolina. It was decided that her father’s younger brother, Commodore Alexander Henderson, and his wife, Catherine, should adopt Maud and take her to live with them in Boston.

I do not know if Maud had met her famous uncle before she became his ward. More than distance had separated the two families. Commodore Henderson had entered the navy in 1851 and the following year, as a young officer, cruised the Far East with Commodore Perry. It was on that voyage in 1854 that Perry’s fleet sailed into Tokyo Bay and caused the Japanese government to open its doors to the West.

The young naval engineer went on to serve in the Mediterranean and South Atlantic, and in 1861 when his Virginia brother Francis was joining the Confederate army, Alexander returned to the States and served with distinction in the Northern navy throughout the Civil War.

In 1882 when the United States began the task of building a “new navy,” Alexander Henderson was made the engineering head of the Naval Advisory Board, designing the “new navy’s” first vessels and supervising the building of them. When this work was done, he became the Chief Engineer of the Boston Navy Yard, where he was welcomed into Boston’s elite society.

It was into this privileged household that Maud went in early 1888. We can only imagine that she arrived in Boston, physically and psychically exhausted, having, over the last two years, almost single-handedly cared for her invalid parents and her baby sister. She was now orphaned and bereft of the only member of her family still living, a toddler who would be likely to forget ever having known her.

Her Boston aunt and uncle seemed determined to help her enjoy life. At one dinner party she was seated next to the venerable Oliver Wendell Holmes, whose work she knew well, thanks to her stepmother’s tutelage.

Referring to a passage in Poet of the Breakfast Table, Maud said something to the effect that she understood that there was one path across Boston Commons that a young man must not ask a young woman to take unless he meant business. Which path was that? she asked Holmes.

“Ah,” she remembered the elderly doctor saying, “if I were only fifty years younger I would show you.”

But the life of luxury was not for Maud. Less than two years later she entered the Boston City Hospital Training School for Nurses, and after graduation went as a nurse to Hanover, New Hampshire, to what was known then as Mary Hitchcock Hospital. She made a lifelong friend there—this much I do know because in one of her letters from China, she reminds her friend of their climbing a New Hampshire mountain that reminded her of her “psychic” experience in West Virginia.

The Spanish-American War interrupted her time in Hanover and she became for the duration head of the camp hospital at Montauk Point, Long Island. She was barely thirty, but despite her youth and tiny height must have become a figure to be reckoned with. With the end of the war, she turned once again to her childhood dream of telling Chinese children about Jesus and enrolled in the Episcopal Church’s training school for deaconesses in New York City. Maud was ordained as a deaconess in 1903 and then set out for China. She was not to see her native land again for forty-three years.

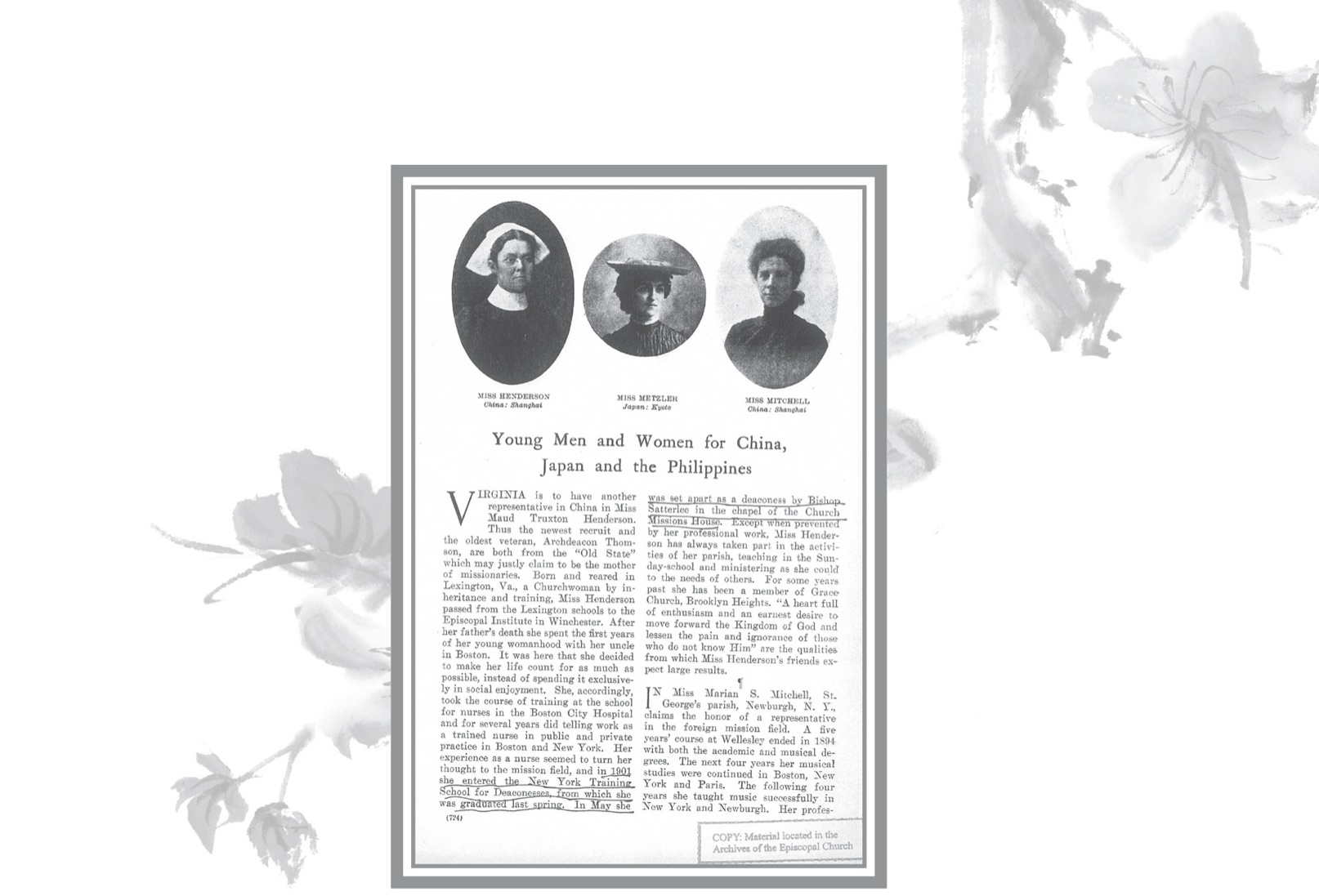

The picture of Maud in the 1903 class of deaconesses shows a serious, determined face—the face of a young woman ready to take charge, and in her early letters from China, she is doing just that. But she had a run-in with an Episcopal bishop who wanted to house former prostitutes in her school for girls, and after briefly joining another mission where she was considered too liberal for their liking, she decided to go out on her own.

Many female babies were abandoned in those days, and Maud was determined to give abandoned girls a home when they had none, providing them with schooling and the skills to make a living and, when the time came, arranging for a good marriage. St. Faith’s, as she called her compound, was financed entirely by donations, some from friends abroad and some from admiring Chinese benefactors.

Over the years hundreds of babies and girls would call Maud “Mother” or “Grandmother.” Her letters, mostly to her half sister, Louise, whom she hadn’t seen since Louise was a tiny child, tell of the joys and hardships of life behind the walls of St. Faith’s. There was the occasion when a tiny blister on her finger turned into a blood infection that nearly took her life. The Episcopal Mission doctor suggested gently that if she had anything she wished to attend to she should do it at once, for “I think tomorrow you will be too weak.”

Maud with one of her many children.

“In an instant,” Maud wrote, “flashed into my mind my father’s last words, ‘Mary, my mother, my Redeemer.’” Despite the fact that she had parted ways with the Episcopal Mission years before, the Bishop of Shanghai, who was ill, sent the mission treasurer to help her put her financial affairs in order, and a priest came to have Communion with her and talk about where she wished to be buried. But Maud, crediting much prayer and good doctors, survived to continue her life with her children at St. Faith’s.

There were no easy times during Maud’s years at St. Faith’s. There was a worldwide depression, so funds were always scarce. China was in perpetual political turmoil. Although the nation became a republic in 1912 under Sun Yat-sen, there continued to be struggles among various local warlords and the rising Communist party. Shanghai was an international city—part of it a French concession and another the so-called International Concession, which included former British and American concessions. The Municipal Councils in these areas excluded Chinese members, and the police and civil servants were foreigners. Even the names of the streets reflected foreign imperialism—such as Jessfield Road, on which St. Faith’s was located.

The international presence offered a certain degree of safety for foreign residents until 1937, when the Sino-Japanese War began. At this point refugees poured into the city. Those who had grown up in St. Faith’s came home and the compound was full to overflowing. The final straw that winter occurred when thieves broke in and stole everything from a Christmas gift of beef to rice, beans, and utensils.

“Bombs, rumours, refugees, measles, simultaneously. One day in the thick of it Grandma [as everyone including Maud herself called her] exclaimed, ‘Where’s the fun?’ . . . [The answer came from the group] ‘On Grandma’s face!’ Yes, Grandma saw the joke. She had asked the question in fun and they had seen the joke.

“Grandma once lost her sense of humor—my daddy had long ago charged me never to lose it because any one finding it might have such a hard time. Well I knew I was up against it because I had lost my sense of humour, and was weeping for it! Will I ever live to see how funny it is to cry for your sense of humour and as the thought came, the rainbow shone through. My sense of humour was welcomed back with a hearty chuckle.”

August, 1938:

“Here we are at it again. Glory [gory] thrust upon us. Now on to Sept. Your New York papers today will be telling you that things are easing up a bit around Shanghai for now. . . For some days I was busy receiving and fixing up refugees. ‘Boy’—faithful helper for over a quarter of a century—was off in the Chinese soldier zone collecting his wife and son and little daughter. One little one already here. I was listening to every knock on the door hoping it was their arrival. They arrived after a trying detour safe and sound. Once, I was opening the door, as I thought for his family, one of ‘my girls’ of twenty-seven years ago was standing there asking if she could come in—‘Come home to Grandma?’ One baby in her arms, another yet unborn, and three daughters and a son. They had walked miles, such a detour. Nothing but the one outfit of clothing they wore. The father too was there. Of course they came in. They were so worn and tired. Roadside food was scarce these days.

“As I write the airplanes are droning overhead, just overhead. One never knows what may happen—by accident or malice prepense. Shrapnel meant for another airplane fell on the roof, close by me in the court where I was standing with several members of the family. Roof tiles were broken and thrown aside. The hot piece lay smoking on the roof, and on touching broke into four pieces. I am not an enthusiast about collecting red-hot war trophies, but I am treasuring these bits. No one was hurt. If the largest, if either, had struck us we would not now be telling you about it. The boom of cannon and anti-aircraft fire has been quieter these last few days, and the noise of the machine guns. And I sleep wonderfully well—truly. And with this great family for every reason I must keep everything as normal as possible. Kindergarten, grade school and sewing hours, prayer time as usual though for 143 big and little I stand looking on, encouraging to quietness, the kindergarten songs are punctured by the boom of cannon.

“Age seventy (Chinese count [in China everyone becomes a year older on New Year’s Day]), temperature hovering around in the nineties 85.6 yesterday, hotter today. One of my former pupils, an orphan boy is living here and working in the Stadium, adapted as a soldiers’ hospital and full of the wounded, quite nearby. Another ‘child,’ pupil once, then teacher, goes to another hospital for night duty tonight. We are in the thick of it.”

There was no mail going out in those days, so the letter begun in August is continued in September and is still being written in November.

“September 6th. Pretty busy. Yesterday the temperature was 97.7 in the shade and plenty moist. Today about the same. In the meantime things are pretty lively, in and out . . . Today when the new land-lord, with his eviction bombs was serving his notice on the many years lord of the land, the Great Land Lord staged a thunderstorm. Such an afternoon—which was which? As I went my rounds, looking after [chores] and folks I found my silly brain saying over a rhyme that Mary Hunter used to say in the old days long ago:

‘Charlotte, when she saw his body

Carried by her on a shutter,

Like a well conducted person

Went on cutting bread and butter.’

“One has to ‘go on cutting bread and butter.’ I found myself seeing the old dining room at 85 State and the group around the table and smiling with them. . . . The food problem is not an easy one. Last week we were reduced to one egg. It was boiled for me for my breakfast, but I voted it to the nurse who was going out to be with the wounded soldiers . . .”

As terrifying as the period of bombing was, the time of occupation was worse. St. Faith’s was located on Jessfield Road next door to Japanese headquarters. Maud did not dare let any of her girls out of the gate for fear that they might be raped and even killed. She related with horror stories of twenty-four young women who answered ads for office jobs only to be locked in and their clothes taken away. Twenty-three were never heard from again. The twenty-fourth managed to obtain clothes of a Japanese man and somehow made her way home. Her parents, overjoyed to see her, were nevertheless concerned for her haggard appearance and, of course, begged to know where she had been and what she had been doing. “Oh,” she said. “I’ve been a little unwell and could not come. Now please just let me go to bed.” She went into her room and wrote a note detailing the horrors she had endured and committed suicide. “I still pray,” Maud said, “for strength to carry on, until this tyranny is passed.”

Marian Craighill, the wife of the Episcopal Bishop of Anking, told of visiting Maud in May of 1938. “Last Sunday afternoon Alma and I made an interesting call on Deaconess Henderson . . . I had heard a lot of how she lived absolutely like the Chinese around her and how she shared her bedroom with the babies and how she did everything for the orphans who came to her—your only credential seemed to be that of need. I went as far as the door with Pearl Buck in 1927 to see if she would take in her amah’s unborn child if it turned out to be a girl—and she had the only place that would, Pearl said. . . . With this introduction you can see my real curiosity as we pounded on the wooden gate in a narrow crowded alley off from Jessfield Road. At first we thought we would pound in vain, but finally we heard a voice and through the chinks we saw Miss Henderson, rattling with keys. As she opened the gate she asked us if we thought we could get in, for the courtyard was flooded and we had to crawl along benches. Right in front of us was the main room of the Chinese house she lives in, simply full of recumbent figures of young girls, taking their afternoon rest. They were covering every inch of space, and the wooden affairs they were lying on proved later to be their desks and benches, and still later their dining tables when they brought in a kind of orange peel tea as we were leaving. . . . They were all of them her old children, who had returned to her when the Japanese drove them out . . . [T]he thing that struck horror to my soul was that they are next door to Japanese headquarters, and she doesn’t dare let the Japanese know of the existence of these girls, so they literally never go out.”

After describing Maud’s own crowded bedroom with its faded pictures of the Lee family on her wall, Mrs. Craighill described Maud as “71 years old, dressed in an ancient Chinese type garment, with the charm of manner and the lovely voice of a cultured gentlewoman of Virginia.” [The Craighills of China, Marian G. Craighill, Trinity Press, 1972, from pp. 221–223.]

After Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, there are no letters from Jessfield Road. As I said earlier, my parents told me a story they had heard from someone, that when at last the soldiers came to take Maud’s girls, she stood in the doorway and said they would have to kill her first. Whatever the truth of that account, it is true that she was somehow able to stay on at St. Faith’s long after most foreign nationals had been taken to detention camps. She was finally interned, sometime in 1944. Sadly, I do not know what became of her beloved children and grandchildren when she was no longer there to care for them and protect them.

After the war ended, there was a flurry of correspondence among various persons in China and the United States, trying to figure out exactly what to do with Maud Henderson. St. Faith’s no longer existed and she was too old to start all over again. She was not the responsibility of the Episcopal Mission, having left its jurisdiction. She yearned to go “home” to Lexington, but the people who knew and loved her there were long dead, and their surviving children could not imagine what they would do if the elderly Maud should land on their doorsteps. Strangely, there are no letters from her half sister and her family. The only relative that stepped up was Thomas Hale, who was the husband of her cousin Elizabeth, the commodore’s daughter. In 1946, he arranged for her passage back to America and several stops along the way, though letters from her hosts seem less than gracious, asking, for example, that they be reimbursed for the cost of housing Maud for a couple of days. She had a visit to Lexington and was interviewed at length by the local newspaper. In the article she expressed her joy to be in the place that she so loved as a girl, but there was no permanent welcome there. It was finally agreed that she should have a place in the Episcopal Home in Richmond. It was from Richmond that she went to see her old friend in Hanover, New Hampshire, and later came to visit our family and revisit haunts of her childhood in Charles Town and Winchester.

It makes me sad to know that there were not many happy times after that. She began to decline physically and mentally and finally died in 1956 at the age of eighty-five.

The newspaper accounts of her return after forty-three years in China tell of the old lady I remember, recalling her special relation to General Lee and his family, bragging that she got respect from the commander of the Japanese detention camp when she told him that her uncle had sailed into Tokyo Bay with Commodore Perry.

“After her fruitless search for General Lee’s portrait in Commodore Henderson’s old sea chest,” a Richmond Times-Dispatch reporter relates, “Miss Henderson walked over to her bedroom mirror. Dozens of snapshots of members of her Chinese family are stuck around the edges of the mirror.

“She identified some of them. This one married a minister. That one became a Red Cross worker. Another lost the sight of one eye, but the doctors saved the sight of the other.

“‘Sometimes I get homesick for China,’ Miss Henderson confessed.”

When the reporter asked her to point to her most satisfying memory of those years, she recalled a time when anti-foreign feeling was running high in Shanghai. A Chinese boy approached her outside her door, pointed, and yelled: “She is a foreigner! She is a foreigner!”

But her own children shouted back: “She is no foreigner. She is the grandmother who belongs here.”

And there is a letter she kept. It is undated, but was probably received in 1950.

My dearest Friend,

As I am urging our students to write a note to their mothers away from Shanghai, I think of you as a mother to so many of our Chinese girls. The greatness and depth of your love only God knows how to measure and reward you. Thinking of you has always been an inspiration to me. I love you.

Lovingly yours,

Tszo-Sing Chen

She was proud to have been kissed by Robert E. Lee. I am proud to have been kissed by Maud Henderson.

I can’t resist adding a family story here. After my mother died, my father insisted on moving to a retirement home despite the fact that we had bought a house with a first-floor room and bath so he could live with us. “Then you’d want to go somewhere, and you’d say, ‘What will we do with poor old Pop?’” At the retirement home was a woman who took a great shine to Daddy, but whose dementia made her a bit intimidating to the rest of the residents. So when he died, everyone was afraid to break the news to her. But when someone finally did, she said: “Oh, that Mr. Womeldorf. He was such a gentleman. He’d make Robert E. Lee look like a hobo.” My regret when I heard that story was that I couldn’t share it with my father. He would have gotten such a laugh from it.

Note: Many of Maud Henderson’s letters from China can be found in the Archives of the Library of the University of North Carolina. I am also indebted to The Episcopal Historical Society for other correspondence.