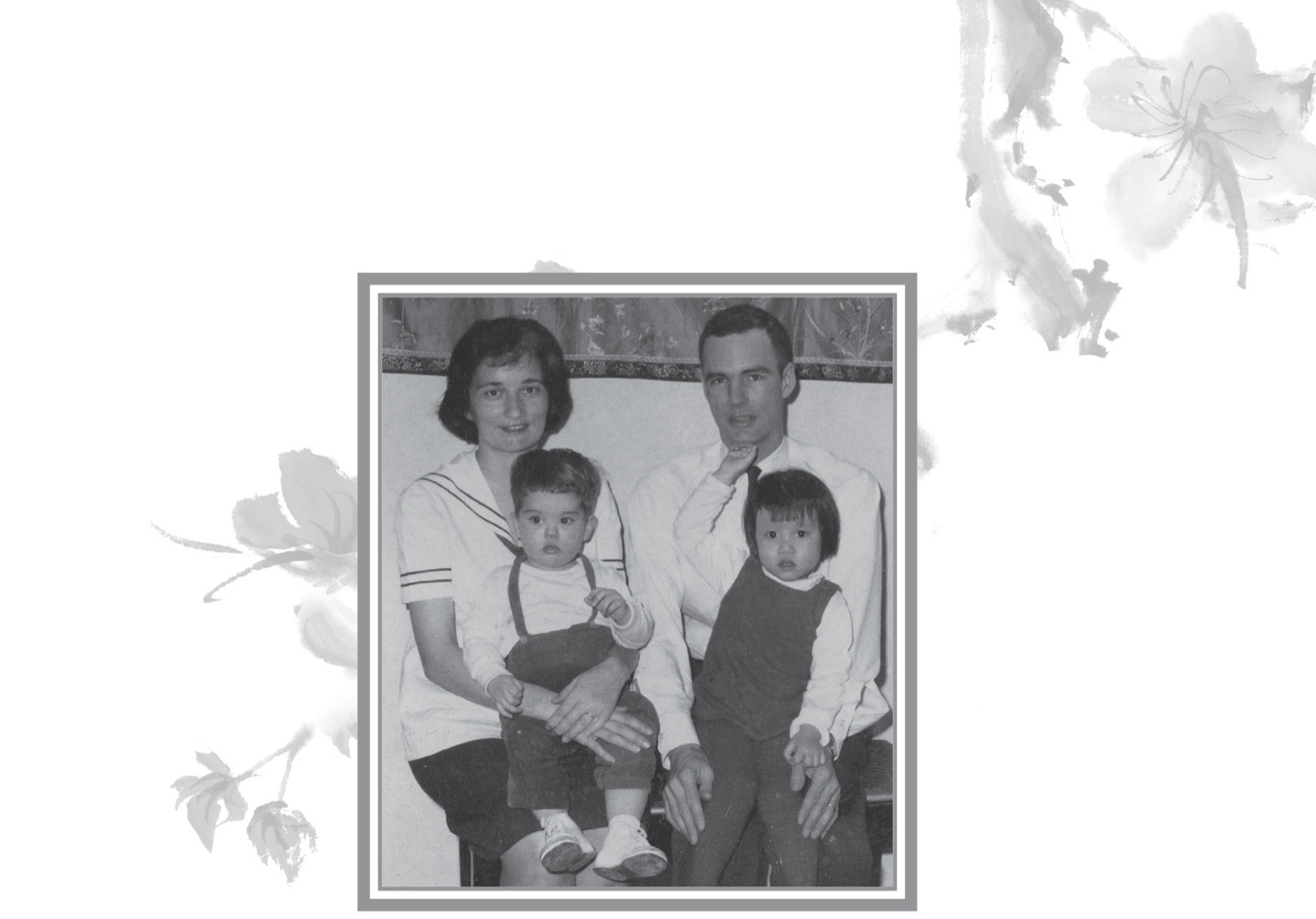

Soon after Lin came.

Motherhood

Many of the young girls I talk with these days want to grow up to be famous. I probably wanted to be famous too, sort of—I mean, why else would I so love performing that I dreamt of becoming a movie star? But even more than famous, I wanted to grow up to be a mother. Outdoors, with the boys on Piedmont Avenue, I played street football, marbles, and junior commandoes, but in my secret indoor life I cherished my dolls. They would have to do until I grew up and had real children. As it turned out, I had four children in just over four years, but for a long time it looked as though there’d be none at all.

Nearly all my friends and classmates had become parents while I was still a single lady missionary in Japan with no prospects of a husband, much less children. I remember standing on the train platform in Ashiya one day surrounded by small black-haired Japanese school children, saying wistfully to myself: “I want one of those.” But back in the late fifties and early sixties, single women were not allowed to adopt children, so it looked, as I approached my thirties, as though I would miss out on my dream of motherhood.

But then, when I was twenty-nine I met John Paterson and we were married the summer before we both turned thirty. On our honeymoon we decided that we would have four children—two the old-fashioned way and two by adoption. We were both concerned that the world’s population was exploding, and that in that population were children who needed families. The adopted child would come first. It would give him or her status as the eldest.

In Japan I had visited orphanages for the children born to Japanese women, children whose fathers were members of the American occupation. These children had no place in either country. We had been married less than a month when I wrote to a friend who did social work in Japan and asked her to make inquiries for us. My Japanese was still quite good in those days. It made perfect sense to us that we should adopt one of these forgotten children. My friend wrote back at once saying that it would not be possible. The Japanese government had just passed a law that Amerasian children in Japan could only be adopted into families in which at least one of the parents was Japanese. The fact that the orphanages were full, with almost no eligible parents stepping up to adopt, seemed to be beside the point. This law was later changed, but at the time it effectively ruled us out. However, my friend gave us the address of International Social Service, an agency that was doing adoptions of children from Hong Kong and Korea. My Mandarin was gone and I had never spoken Cantonese, but I did have roots in China, so we applied for a child from Hong Kong.

A social worker came out from a Buffalo agency and did a case study and then there was nothing to do but wait. We bought a child’s rocking chair as a sort of talisman for the child we were waiting for, and I would look at the chair and daydream about a little girl with black hair sitting in the chair and rocking happily. But the wait went on. At this rate, we thought, we’d soon be too old to have those two homemade children. But a pregnancy that started out with hope ended in a miscarriage.

After the miscarriage, the prospect of motherhood seemed as dim as it had been since before my marriage. No progress was being made on the adoption front in the more than a year since our initial inquiry, and I didn’t seem to be able to conceive again. We moved to Princeton so that John could pursue a graduate degree at Princeton Seminary and where, as I said earlier, I started teaching at the Pennington School for Boys. John had accepted a part-time job as assistant pastor in the First Presbyterian Church, and not long after we arrived in town, the senior pastor and his wife invited us for dinner. The door was opened by their preschool son, who asked where our children were. I said we didn’t have any children.

“Don’t you want to have some children?” Wayne asked.

“Yes,” I said, “but we just don’t have any.”

“Pray to Jesus,” he said, as though that would solve everything. Don’t ask me to explain it, maybe Wayne started praying for this poor childless couple; at any rate, in a little more than a month, John Jr., was on the way.

At almost the same time that I found out I was pregnant again, we got a call from one of our references in the Buffalo area to say that International Social Service was trying to locate us. Did we still want a child? Of course we did. The agency sent us a picture of the little girl they had matched with us. She was a determined-looking six-month-old with huge dark eyes and fierce black hair that stood straight up on her head. We fell in love at first sight. The orphanage had given her a name—Yeung Po Lin. The Po meant “precious” in the Canton dialect and was also part of my own Mandarin Chinese name, which was Wong Ja Bao or Wong (our family surname ja, a middle name we all had, and bao, “precious”), and her birthday was October 30—the day before my Halloween one. Surely she was meant to be our daughter.

But there was a problem. The state of New Jersey would not recognize the family case study that had been done in Western New York. We would have to start all over again. New Jersey prided itself on very low taxes, which translated means very few government services, so by the time a social worker came to our apartment I was great with child. She took one look at my stomach and decided that John and I were out of our minds. Why would we be trying to adopt when we could obviously have children? She went off on her own maternity leave and never finished the home study, but fortunately another much more sympathetic worker was put on our case. The following June, John Jr. was born. Still nothing was happening with the adoption process and our daughter was spending her first two years in an overcrowded Hong Kong orphanage.

Our friendly social worker would not give up and kept pushing until she found out that our papers were languishing on some bureaucrat’s desk because on some of the pages Paterson was spelled with one t and on others with two. Then, when everything seemed cleared up, there was a chickenpox epidemic in the orphanage and little Po Lin was not to be allowed to leave until all danger of contagion was past.

When we were sure that our daughter was truly coming, we began eagerly to tell family and friends what was about to happen. My China-loving parents were overjoyed—a Chinese granddaughter in the family—but John’s father was deeply concerned. He predicted darkly that a child who had spent her first two years in an orphanage would never be able to trust or to adapt to family life. One of the friends we felt closest to in Princeton was appalled. How could we do this to little John? He would never recover from the shock of a sudden sister. And how dare we snatch a child from her own culture and bring her into our own? My confidence was shaken. We were taking a two-year-old out of the only life she knew and plunking her into an environment that would be alien in every way. I had no worries about happy little John Boy—I was sure he would quickly adapt—but what about our new child? What were we doing to her?

At just this time, I went to a weekend private school retreat with several of my students. One of the teachers that I met there was Chinese, so I screwed up my courage and asked him if I could speak with him privately. He listened thoughtfully as I told him what we were proposing to do and how some of our closest friends and family members were telling us that we were making a huge mistake. What did he think? Were we being fair to this child?

“I’ve just met you this weekend and I don’t know your husband at all,” he said. “But I know enough about the situation in Hong Kong that I can promise you that whatever you give this child will be better than what she has to look forward to there.” His words somehow assured us that it would be all right to proceed as planned.

We began to think seriously of names for our new daughter. We wanted to keep her Chinese name, Po Lin, but we wanted her to have an English first name that would be special to our family. My grandmother was Elizabeth, my mother was Mary Elizabeth, and my older sister was Elizabeth, so we settled on Elizabeth PoLin Paterson and began trying out various nicknames. My older sister was Liz, an improvement on Lizzie, to be sure, but Liz seemed too old a nickname. I looked at the rocking chair and imagined a pig-tailed daughter called Betsy.

The long-awaited day finally arrived. Our daughter would be handed over to us planeside in LaGuardia Airport. The three of us waited—John was holding six-month-old John Boy and I was trying to hold myself together. John and I were excited and terrified. The baby, even far past his bedtime, was his usual bouncy happy self. There was another family waiting for their new daughter as well. In addition to the parents, there were three older children, thrilled with the thought of a new baby sister. We exchanged nervous conversation with the parents and took each other’s addresses. Finally, after all the passengers had deplaned, a flight attendant appeared carrying a chubby smiling baby. The other family’s name was called and, as the mother stepped forward to claim her, the little girl put out her arms. “Mama!” she said.

“Your baby is coming.” The way the flight attendant was not smiling when she said it made me even more anxious. What was the matter with our baby?

At length a Chinese woman emerged. She looked exhausted, and the tiny, dazed little girl she handed to me simply flopped in my arms. “She hasn’t slept since we left Hong King,” the escort said, indicating that neither had she. I struggled to hold our new daughter. She weighed hardly anything but she was totally limp. Had she never been cuddled? I couldn’t help but wonder what we had gotten ourselves into.

We drove back to Princeton that night, and my new daughter dozed off in my arms. We’d put a crib for her in John Boy’s room, thinking that having another child about would feel less lonely than a room alone, but the moment I put her down in the crib she woke with a start and began to cry. That was Tuesday night. Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, and Saturday nights were the same story. John and I took shifts walking the floor carrying her, because it was only when we were actually walking that she would fall asleep. If we stopped walking or worse, sat down, she’d wake up; if we tried to put her in the crib, she’d sit bolt upright and begin to cry.

She never smiled, but when she was sitting in her high chair at the dining room table she at least seemed content. One morning at about five I put her in the high chair and began to feed her. She ate, not greedily, but steadily, through four or more bowls of cereal and at least three eggs. At ten o’clock I put her down. She needed to know that there would be more meals to come—that she could count on three each day.

It was quickly apparent that our little daughter looked nothing at all like a Betsy. I called my mother on the phone. “She’s too tiny to be called ‘Elizabeth,’ and ‘Betsy’ and ‘Beth’ just don’t fit.” “Why not Lin?” asked Mother, who had yet to see even a photo of the child. It felt perfect, and she’s been Lin ever since.

Little John loved racing around in a walker and Lin steered clear of our tiny reckless driver, but otherwise, if she were put down in one spot, she would seem almost rooted to it until picked up and moved somewhere else.

Since neither John nor I had had any sleep to speak of by Sunday morning, I suggested he go on to church with John Boy, who loved the nursery at church (well, he pretty much loved everything), and I would stay home with Lin. We had a set of colored blocks of different shapes that fit neatly into a square box. Trying to entertain her that morning, I dumped the blocks out on the floor and showed her how they fit back into the box. Then I dumped them out again. She studied them and began very carefully trying to fit them back into place. Oh, dear, I thought. This is too much for her. She’s a two-year-old that has hardly slept for a week. So I helped her rearrange the blocks so they would fit. She gave me the same determined stare that looked out from her baby picture, watched me finish the job, and then she picked up the box and dumped all the blocks on the floor. The look she gave me made me know I was not to help, so I put my hands in my lap while she proceeded to fit each block into the box. It’s going to be all right, I thought. She’s really smart.

A bit later the two Johns returned from church. The senior pastor had asked him that morning how things were going with our new daughter and John had told him how we were getting practically no sleep—that Lin was sleeping only when we were walking the floor with her. Dr. Meisel offered to call a church member, a psychiatrist, who happened to be Chinese; maybe Dr. Wong would have some ideas that might help.

By the time we’d finished lunch Dr. Wong called. He asked if he and his wife could drop by, not for a professional visit, but just in friendship. I still remember the thoughtful way he put it, reassuring us that he didn’t expect the poor preacher’s family to come up with his professional fee.

I put John Jr. down for his nap, and Lin was watching me wash dishes when the Wongs arrived. (It seemed a happy coincidence that we had the same Chinese name.) I heard Dr. Wong suggest to John that he take him in to see the bedroom. Mrs. Wong, a tall, strikingly beautiful Chinese woman, came to the kitchen door. Lin looked up at her as though startled. Then Mrs. Wong squatted down to Lin’s level and, in a very gentle voice, said something to her in Cantonese. Lin gave her a long stare and then walked over to me.

“You don’t need to worry,” Mrs. Wong said quietly. “See? She’s already chosen you to be her mother.” I knelt beside my little girl and put my arm around her. She didn’t pull away.

In the bedroom, Dr. Wong and John were consulting. The doctor suggested that John take the railing off the crib and lower it as much as possible. “That railing is in the way of her getting to her high chair, the one place in the house where she feels safe. And she probably slept much closer to the ground in the orphanage. You can put a mattress beside the crib, so if she rolls out, she won’t get hurt.” John fetched a mattress off a twin bed in the guest room, and then the men came to the kitchen. Lin had fallen asleep against my shoulder.

“She’s asleep,” Dr. Wong said. “Why don’t you put her in the crib?”

I started to protest, that she would only wake up screaming, but he was the doctor, so I obeyed. I laid her in the crib, and sure enough she sat right up, but this time she looked around, took in the new set-up and, without a sound, lay back down. She was still asleep when the Wongs left. She didn’t sleep more than an hour that afternoon, and she didn’t sleep through every night for several weeks, but it was the beginning of a new, much better time for us all.

Besides food, which she could never get enough of, Lin loved two things: a tiny rubber dog and John Boy. She wouldn’t talk to Big John or me in Cantonese or English, but we could hear her talking to her baby brother in the bedroom. “Say, ‘ball,’” she’d order. And at six months, John said “ball.” And, certainly partly thanks to Lin’s coaching, he was talking in complex sentences before he was two. In the hall there was a full-length mirror and Lin would take the dog to the mirror and have a whispered conversation. I was never sure in what language, but she and the dog were obviously chatting with their mirrored selves.

Changing John Boy’s diapers was always a hilarious affair. I would tickle his tummy and he would shriek with laughter. Lin would stand by looking at this scene with what seemed to me a disapproving stare. But one day when I was changing her diapers she took my hand and put it on her tummy, so I tickled her. My reward was her first smile.

We took the children to Winchester to meet my parents in February. We felt by then that Lin was comfortable enough in her new home to risk a trip away from it. As far as Lin and Mother were concerned, it was love at first sight.

Lin talking to the mirror.

By this time Lin was not only sleeping at night, she might even take a nap. She was upstairs asleep when one of my mother’s friends arrived carrying a Raggedy Ann doll she had made to give to our little new daughter. The friend was so proud of her handiwork, she wanted to rush upstairs and wake up Lin to give it to her. She was almost at the bottom stair before I stopped her.

The doll, like all Raggedy Anns, had bright orange wool hair, black button eyes, a red triangle of a nose, a sewn-on grin, but, unlike any I had ever seen, this doll was at least four feet tall. If your mother had read you stories about Raggedy Ann and Andy from the time you were a tot, you’d be thrilled to have a Raggedy Ann of your very own with a secret candy heart sewn inside. You might even like one more suitable to cuddling you than vice versa. But I was sure poor Lin would be terrified. I was afraid the sight of a stranger bearing a huge, even stranger doll would annul all the progress Lin had made.

As I was trying to suggest that we go cautiously, Lin appeared at the top of the stairs and looked down at us. The woman held out the doll.

“Baby!” Lin exclaimed, and came straight down the stairs to claim her new treasure, which was bigger than she was. Baby, she was never to know any other name, stayed with us until she was loved into literal rags.

And as for my unhappy father-in-law, before much time had passed, he’d forgotten all about his dire predictions. Lin had become his favorite of our children.

John Jr. was no longer John Boy when I realized the neighborhood children thought it was hilarious that I called my tiny son “Jumbo.” It was the Southern accent that did it. I didn’t want him going through life having people making fun of what his mother called him, so long before his second birthday he was simply “John,” and, of course, the confusion of having two people by the same name in one family ensued. And, yes, I do remember his first complex English sentence, spoken when he was twenty-one months old. We were passing the public tennis courts in Silver Spring when he said: “When I get to be a big man, I play tennis ball like my daddy.”

We moved to Maryland when David was well on the way, but we had to live for several months in an apartment in Silver Spring before the house we were buying in Takoma Park was vacated. So six days before David’s actual birth, we moved into the house we would live in for the next thirteen years. The obstetrical practice recommended by my Princeton doctor worked out of George Washington University Hospital in downtown DC. I had nightmares of trying to get to the hospital through Washington rush hour traffic, but David conveniently decided to be born on Sunday morning. We went through nearly empty streets to the hospital, checked in, and David was born at eight a.m. It happened so quickly, the doctor almost didn’t get there in time.

John welcomed his new son, and then went back and preached the Sunday sermon that he had written about the Prodigal Son. It was entitled “The Father’s Two Sons.” He thought that was a delightful coincidence. I only hoped that neither of our boys would turn out like the Biblical pair—the one a wastrel and the other a self-righteous prig.

Before long people began to remark how much our two boys looked alike and Lin began asking for a sister that looked like her. We had always planned to adopt a second child, but we now had three children and a mortgage and a very modest salary to support us all. The cost of adopting from overseas again would be beyond our means. We went to the local Lutheran Social Service that we were told was the best agency in the area and asked if they ever had an Asian or part Asian child available for adoption. They hadn’t had such a child for years, they said, but they had just been asked to handle the adoption of American Indian children. Would we be interested? In the pictures the social worker showed us, there were many children who could pass Lin’s test, so we agreed. Could we just wait, I asked, until David was at least two before we got a new baby? Even then we went from childless to the parents of four in four years and six weeks.

We were matched in the late spring of 1968 with a baby who was half Apache and half Kiowa. Her birthday was February 22, so her foster parents who had taken her home that day called her “Georgie” in honor of our first president. There was no way a daughter of mine was going through life with that name. So we spent a lot of time trying to figure out what to name her. We had thought we could wait to name her after we actually saw her, but a day before she was due to arrive, we were told that the state of Arizona was demanding a name to put on her amended birth certificate. We had decided on Mary, a family name on both sides, and the name of my closest friend from early days. We thought briefly of Mary Helen or even Helen Mary, which would combine my mother’s name with that of my younger sister. John decided he preferred Mary Katherine, but Lin had kept her Chinese name. Wouldn’t it mean something to Mary to have either an Apache or Kiowan middle name?

A member of our church in Takoma Park worked for the Bureau of Indian Affairs. I called Ken up and asked him if anyone in his office could help us. The problem was we had to send the name to Arizona by the end of the afternoon and it was already mid-morning.

About two hours later, we had a call from Ken. “Do you have pencil and paper handy?” he asked. When I did, he began to spell a name. It seemed to go on forever.

“Ken,” I said weakly, “could we have something a little shorter?”

“Listen,” he said sternly. “I called Will Rogers Jr. in Oklahoma and he sent a runner to the reservation to the old woman who gives names, and this is the name she sent back. I think you’d better keep it.”

I showed the name to John. “Maybe we’d better drop the Katherine,” I said.

He looked stricken. “But I’ve always wanted a little girl named Mary Katherine,” he said. I doubted that, but we didn’t have time to argue. We sent the name: Mary Katherine Nah-he-sah-pe-che-a Paterson. The name means: “Young Apache Lady.” And we were right. She loved having that name. I asked Mary when she got married which of her many names she was going to drop, and she said, “None of them.” So she is our five-name daughter, though she usually resorts to initials for the three middle names.

We went to the recently opened Dulles Airport to meet our new daughter. Two-year-old David and four-year-old John were racing back and forth across the giant, empty concourse that the airport was in those days. Lin was very still, and John Sr. and I were, as we had been when waiting for her, our nervous selves. At last the social worker came through the gate carrying a very large five-month-old.

“Can I hold her,” asked tiny five-year-old Lin.

The baby was about as large as she was, but how could I say no? I told her to sit down and I would put her new sister on her lap.

Lin put her arms around Mary and gave a beatific smile. “She’s got the same color hair, and the same color eyes, and the same color ears as me,” she said.

Meeting Mary at the airport 1968. Social worker who brought her from Arizona on left.