I like yak. Bulky, black and shaggily clad, yak convey a rugged elegance; they belong to bitter storms and barren uplands.

—George Schaller (1980:63)

I begin by describing the salient features of Dolpo’s agro-pastoral system. The aim is to evoke a place, its people, and their modes of life, so that the transformations of Dolpo—and, indeed, the entire trans-Himalayan region—can be better understood. In this first chapter, I describe Dolpo’s livelihood practices, circa 1997. Though these practices are conditioned by historical and geopolitical circumstances (which I relate in later chapters), and before complicating Dolpo’s story with the exigencies of the twentieth century, the region’s livelihood strategies are first sketched in situ to present a sense of what daily life in Dolpo is like.

It is necessary to understand life in Dolpo as a series of interrelated production systems. Agriculture, trade, and livestock movements are overlapping and coextensive, but in these early chapters I will parse out these livelihood strategies to convey Dolpo’s daily and seasonal rhythms. Where possible, I situate my voice in the observed past rather than the ethnographic present, since the latter tends toward descriptions that are timeless and therefore static.1

DOLPO’S PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT

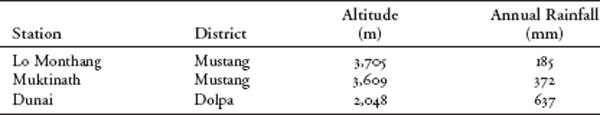

Set deep in the western Himalayas of Nepal, Dolpo encompasses a series of rugged mountain ranges shot through with precipitous valleys. Geologically speaking, this region falls within the Tibetan sedimentary zone.2 Natural conditions limit the subsistence livelihoods possible in Dolpo. To the southwest lies Dhaulagiri, the sixth-highest mountain in the world (8,172 meters). This massif and its outliers create a rainshadow that determines much of Dolpo’s climate. Though no meteorological records have been kept in Dolpo, its valleys are reported to receive less than 500 millimeters (mm) of precipitation yearly (see table 1.1).3 Beyond scanty rainfall, Dolpo’s climatic conditions—short growing seasons, sharp seasonal differences in temperature and rainfall, high winds, and heavy snowfalls—rigidly constrain plant growth (cf. Mearns and Swift 1995). Grasslands are locally reported to begin growth in the fourth Tibetan month and go dormant by the ninth month.4

Plant species adapted to high-altitude conditions, like those found in Dolpo’s rangelands, display high photosynthetic efficiency and rapid carbon dioxide assimilation, even at low temperatures (cf. Walter and Box 1983). Plants in these harsh environments grow slowly over the course of a long life. The entire aboveground portion of these plants dies when species go dormant each year (programmed senescence) while the perennial bud—the reservoir of new growth—remains below ground.

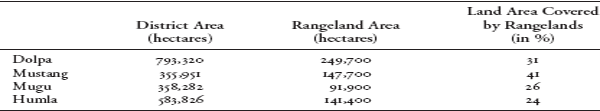

Rangelands are the most common vegetation type in Dolpo (see table 1.2). The Society for Range Management (2001) defines them as lands on which “the indigenous vegetation is predominantly grasses, grass-like plants, forbs or shrubs.”5 Rangelands include natural grasslands, savannas, shrublands, deserts, tundras, alpine communities, marshes, and meadows. Rangelands are also defined in utilitarian terms, as expanses of land suitable for grazing by ruminant animals as well as areas unsuited for cultivation due to low and erratic precipitation, rough topography, poor drainage, and cold temperatures (cf. Heitschmidt and Stuth 1991; RanchWest 2001).

Table 1.1 Annual Precipitation in Northwest Nepal (1974–1990)

Dolpo’s rangelands are diverse, a function of its wide altitude range—between 3,000 and 5,000 meters (m)—and extensive area (see table 1.3). The flora of Dolpo has affinities with the adjacent vegetation of the Tibetan Plateau.6 Most plants survive by lying low, often as “cushion” plants, or by protecting themselves with mechanical and chemical defenses. Plants in Dolpo have adapted not only to a cold and windy environment but one in which herbivores have been a constant presence for at least 10,000 years.7 Dolpo’s alpine rangelands extend from 4,000 to 5,000 m and are the primary summer grazing grounds for domestic livestock. They are also core habitat areas for wild ungulates such as blue sheep (na or naur) and rodent species like marmots.

Altitude and aspect play important roles in vegetation cover and type. Variables such as slope and exposure to wind also contribute to environmental variation at the community and species scales. In Dolpo, shrubs such as rhododendrons are common on north-facing slopes, which are exposed to less sun and hold more snow during the winter, insulating soil and plants. On north-facing slopes, shrubs are taller, and there is a higher percentage of vegetation cover than on the opposing aspect. By contrast, on south-facing slopes, it is more difficult for plants to establish and recruit. Drought-tolerant sedges (e.g., Kobresia spp.) are common on this aspect, which is exposed to a wide range of conditions—high winds, intense sunlight, and bitter cold—without the insulation of snow (cf. Ekvall 1968; Carpenter and Klein 1996).

Table 1.2 Rangeland in Contiguous Districts of Northern Nepal*

*Adapted from Land Resources Mapping Project (LRMP) 1986; DFAMS 1992; and Miller 1993.

Table 1.3 Rangeland Types in Dolpo

| Vegetation |

Zone Altitude (in meters) |

| Subalpine |

3,000–4,000 |

| Alpine |

3,500–4,500 |

| Steppe |

4,000–5,000 |

AGRICULTURE IN DOLPO

Dolpo is home to some of the highest permanent villages in the world. Agriculture is the subsistence base of life here, but it provides only four to seven months of food every year (cf. Jest 1975; Bajimaya 1990; Sherpa 1992; Valli and Summers 1994). The basic unit of land in Dolpo is called a shingkha, which measures the productivity of a field rather than its size: one shingkha produces approximately 500 kilograms (kg) of barley or 250 kg of potatoes.8

Arable land lies between 3,800 m (Shimen village) and 4,180 m (Tsharka village). At these altitudes the growing season is short, and Dolpo’s villagers can harvest crops only once a year. In addition to climate, water is a limiting factor in Dolpo’s agricultural system. Irrigation canals are sometimes kilometers long, fed by reservoirs and rivers, and bring water to terraced fields carved long ago from this rugged landscape. Irrigation canals require constant maintenance and communal gangs rebuild these aqueducts every year.

Barley is the most important crop, though others are cultivated, including buckwheat, millet, mustard, and wheat, as well as potatoes and radishes.9 Melvyn Goldstein and Cynthia Beall (1990) report that at least half of the calories consumed by Tibetan pastoralists derive from grains, particularly barley.

Agricultural land in mountainous regions like Dolpo is scarce. True to their alluvial origins, slivers of domesticated land are still subject to flooding, and fields are frequently lost to Dolpo’s rivers, reclaiming relict floodplains. But the social organization of culturally Tibetan communities limits land fragmentation and has reproduced a standard of living higher than might be expected. Tibetan-speaking groups that are agriculturalist tend to be polyandrous, which produces large extended households and passes down undivided property holdings from one generation to the next (cf. Levine 1987). Polyandry in Tibet has most often been explained functionally—an ecologically driven response to limited agricultural land, though this contention has been challenged on the grounds that not all Tibetans practice polyandry. Yet Tibetans themselves tend to explain polyandry in functional terms.

Land descends through the eldest son, ensuring that family plots remain feasibly sized, without intragenerational subdivision into smaller and smaller plots. If only daughters are born, a household’s fields are most frequently passed on to the “adopted son” (magpa), who marries into the family and moves to his bride’s village. Widows do, however, hold property rights and assume control of their husband’s land upon his death. Sales of agricultural land in Dolpo must be approved by the village council, which can veto these transactions, especially if they are with outsiders.10

The traditional land tenure regimes of Dolpo have been subordinated within the Nepal state. Beginning in 1996, the government sent teams of surveyors to delineate private agricultural land in Dolpo. This process hurled villagers into a world of title deeds, land offices, fees, assessments, and applications. There they faced bureaucrats, land surveyors, and government agents whose rules of procedure and decision-making were unfamiliar and asymmetrical, bearing out the contention that “those who are mapped … have little say about being mapped” (cf. Agrawal 1998:74; Scott 1998). The government surveyors measured private land holdings, calculated taxable areas, and fixed household ownership over fields. These properties were cross-registered with identification papers kept at Dolpa District headquarters in Dunai. The government’s land registry (naapi) continued long-standing efforts by the Nepal state to assert control over its peripheral areas by delimiting territory and enshrining individuals’ rights to use and dispose of private property.

In Dolpo’s agricultural system few fields are left fallow, and crops are rotated yearly. Dolpo farmers augment soil fertility by spreading compost made of ashes, sheep dung, night soil, and kitchen midden as fields are being plowed. Tillage is initiated during the fourth Tibetan month, when plow animals are brought back to the village from the winter pastures. Farmers in Dolpo rely upon rudimentary technology—steel-tipped wooden plows and hand tools—and the brute force of animals to plow their fields. The type of animal used for draft labor differs among the four valleys, a function of tradition and local herd composition. For example, Saldang villagers use horses (ta) to plow fields, while those in Tinkyu and Polde villages use yak and yak-cattle crossbreeds to till.

Every year, the head village lama consults the Tibetan almanac and astrological calendar (lotho) to determine an auspicious date to begin planting. On this propitious day, the head lama’s fields are sown first. Animals are forbidden within village limits during the growing season (between the fourth and ninth months) to prevent crop depredation. After planting, the village lamas ceremoniously bless the village’s newly planted crops by circumambulating the fields. They recite texts and play instruments while villagers bear sacred statues and tomes, in tow. In the circle they scribe, the lamas mark off the area where livestock may not pass. Thus, religious rituals coordinate with and reinforce community regulations, which ensure that livestock are dispersed and moved frequently.

Dolpo’s communities have developed systems of infractions and sanctions that prevent open access to communal rangelands and reinforce property lines. Villagers move their herds simultaneously to ensure that pasture use is equitable. The deadline for moving animals between pastures is enforced by local fines that penalize households for each day they delay in moving their animals (cf. Richard 1993). Likewise, in Panzang Valley, before the onset of tilling each spring, any household that owns at least one yak must send a representative to join the group of men sent out to fetch the herds from the winter pastures; anyone who fails to fulfill this obligation is levied a fine by the headman (D., drel-wo).

For farmers, crop depredation by livestock can spell disaster, given Dolpo’s already finite harvest. For livestock, though, fields of buckwheat and barley may prove to be irresistible, set against the scant and widely dispersed forage available in Dolpo’s rangelands. Community sanctions are employed to guard against crop depredation by livestock: the injured party has the right to make a complaint to the village headman, who holds the owners of animals that stray into cultivated fields accountable by setting a fine to compensate for the losses in crops.

In Nangkhong Valley, these fines are proportional to the evidence left by marauders: each footprint found in a field costs its owner a measure of grain. In Panzang Valley, fines are levied according to the size of the animal. The owners of yak or horses must pay two kilograms of barley or twenty rupees for every animal found in a field, while raiding goats or sheep are fined a tenth of this amount. Thus, Dolpo’s households are deterred from abusing others’ private resources. These sanctions appear to cost households more—both in material and social terms—than the benefits they might gain by giving free reign to their animals. Even so, vigilance is the order of the day, as animals are wont to ignore community injunctions in pursuit of greener grass inside the walls of Dolpo’s fields.

Yet the movement of cultivated fields between private and communal use, with the change of seasons, points to multiple understandings of property and resource use in Dolpo (cf. Agrawal 1998). As the summer pastures go dormant, and the high altitudes become forbiddingly cold, the women who attend to dairy production return to their villages for harvest time. After crops are harvested, livestock are released into the fields and there are no restrictions on access to these resources.

Agro-pastoral communities cannot maintain production without cooperative labor and other forms of mutual aid. In his study of agro-pastoralists in the Tichurong area of Dolpa District, James Fisher (1986:176) writes, “Despite the internal cleavages of wealth, status, and power, interpersonal relations in the village are pervaded by an aura of diffuse reciprocity. The most obvious example … is the phenomenon of cooperative labor.” Dolpo’s villagers enter into a variety of social arrangements to cope with annual chronic shortages of labor. Villagers are compelled to perform manual work needed by the community, such as the building of trails and maintenance of irrigation canals. Most agricultural labor is likewise performed in groups, as an exchange of reciprocal labor among friends, neighbors, and relatives within villages. Communal labor gangs capture economies of scale and insure individuals against risks such as illness or accident. They serve important functions not only in agriculture but also in day-to-day pastoral management and fuel collection (cf. Mearns and Swift 1995). These traditions of reciprocal labor may instill in individuals a communal ethic, an antecedent to the sophisticated institutions and practices used to manage natural resources in Dolpo.

The intensely seasonal nature of Dolpo’s livelihoods lends itself to focused and ritualized periods that bring community members together to work. For example, during the harvest season communal labor gangs scythe, thresh, and chaff grain together. These communal workdays are punctuated by play: women gossip and sing songs while weeding, boys and girls flirt and play rough as they take a break from reaping, and men plan trades or tease old friends before they lean their animals into the plow. While planting and harvesting demand brief periods of intense communal labor, intermittent agricultural chores fall to household members, particularly women.

PASTORAL PRODUCTION IN DOLPO

Life in Dolpo rests squarely on animals: even agriculture would be unimaginable without them. Pastoral communities throughout the trans-Himalaya rely upon yak, cattle, yak-cattle crossbreeds, goats, sheep, and horses to carry out their livelihoods. These animals produce goods by the score for Dolpo’s homes, including milk, wool, and meat as well as transportation, draft power, and fuel. Beyond these functional categories of production, livestock play important symbolic roles in Dolpo (as discussed later in this chapter). The livestock a household has depends upon its labor force, available capital, and on the family’s previous economic fortunes. The kinds of animals kept range widely, too, especially the proportions of ruminants to ungulates (i.e., the number of goats and sheep versus cattle).

Yak are the favored livestock, “for all they give and the burdens they carry,” as one Dolpo headman put it.11 The yak was probably domesticated in Tibet, no later than the first millennium B.C. Yak are mentioned in the writings of Aelianus, a third-century author, who called them poephagoi, meaning grass-eaters. There are still wild yak that interbreed with domestic ones on the Tibetan Plateau, mainly in the Changtang Wildlife Preserve and the Kunlun Mountains, though their numbers are precipitously dropping. Domestic male yak live up to twenty years, while females generally live for fifteen to twenty years. Yak reach maturity at four to five years and remain sexually reproductive up to ten years (cf. Khazanov 1984; Miller 1987, 1995; Goldstein and Beall 1990; Bonnemaire and Jest 1993; Kreutzmann 1996; Li and Wiener 1995; Schaller 1998).

Yak are best adapted to survive in Dolpo’s rigorous environment: cold, high altitudes with low oxygen content and intense solar radiation. They can negotiate treacherous terrain, move thirty miles in a day, and carry a load of two hundred pounds through snow at 20,000 feet. Unlike other livestock, yak need supplemental hay only in times of heavy snow. Yak cope with a variety of forage and endure chronic fodder shortages, punctuated by brief periods of peak range productivity.

The hardiness of yak can astound. On one trading trip, a group of caravanners stopped to rest at Palung Drong, the rich pastures between two of Dolpo’s loftiest passes (Num La and Baga La). A pregnant dri (female yak) gave birth that day while the herd rested and grazed. Despite the birth, the beast’s master aimed to get home and drove his animals on the next day. The mother, exhausted, and the calf, awkward, were forced to go on, too. Buckling up, the calf, bleating and bewildered at its rude entry into the world, chased its mother as the caravan set off. Desperate and angry, the mother attempted to escape but eventually submitted to the long walk, her placental sac still dragging behind her as amniotic fluid trailed in the dust.

Crossbreeding of yak and cattle to produce hybrids (called dzo) is commonly practiced in Dolpo.12 These animals combine the endurance and load-worthiness of yak with the higher milk production and physiological tolerance to lower altitudes of cattle. Female crossbreeds are used for dairy production and transport, while male crossbreeds serve as pack and draft animals and are slaughtered for meat. Male crossbreeds are more even-tempered than yak and valued as beasts of burden. Although crossbreeds are fertile, the second generation is less well adapted to Dolpo’s strenuous environment.13

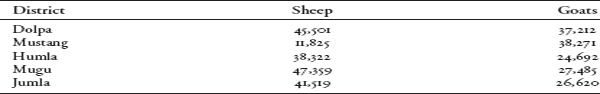

While yak, cattle, and their crossbreeds are central to Dolpo’s way of life, a family’s primary economic investment is in goats and sheep, which are used for wool, milk, and meat. Though large stock like cattle are relatively prolific dairy producers, they reproduce slowly when compared with small stock like sheep and goats, whose reproductive potential permits higher rates of meat extraction (cf. Ingold 1990; Salzman and Galaty 1990). Moreover, sheep and goats are highly mobile and cost less than cattle. Functionally and symbolically, goats and sheep are grouped together in Dolpo, reflected in the local name for these animals—ralug—which means “goat-sheep.” (See table 1.4.)

Horses are draft labor as well as a means of travel in Dolpo and serve also as beasts of burden. Unlike pastoralists in other parts of Central Asia, Dolpo-pa do not harvest and consume mares’ milk. Though they rank low in productivity to their expense, horses are critical animals in Dolpo household herds; most extended families have at least one. Horses are symbols of wealth and social prestige throughout the Tibetan-speaking world, as they are the most expensive animals for a household to buy and maintain. Yet horses are a necessary luxury in Dolpo: in an emergency, it is a three days’ ride to the nearest airport.

Horses figure prominently in Tibetan Buddhist iconography and village mythologies, and specific religious rituals are held to ensure horses’ health. For example, every year horses are ceremonially blessed and receive a square cloth talisman (srung) that holds tiny prayer scrolls. Village priests tie these amulets around horses’ necks to prevent harmful roaming spirits from entering horses’ bodies. These wrapped prayers are said to protect the animal and, by extension, the household’s prosperity.

Table 1.4 Ruminant Populations in Northwest Nepal*

*Adapted from LRMP 1986; DFAMS 1992; and Miller 1993.

Tibetan mastiffs (kyi) are incorporated into the Dolpo pastoral system as livestock guards. Writing about its local breeds, a Dolpo lama boasts, “The dogs from Dolpo are most brave and powerful” (Shakya Lama 2000). Dogs are called upon to challenge wolves and snow leopards, should these predators approach penned animals, and to alert their masters to the presence of unexpected or unwanted guests. Dogs are not used for herding; rather, most spend their lives gnashing teeth and barking, frustrated at the end of a chain.

Cats (shimi) are kept (or rather, tolerated) by some households, seemingly out of compassion and curiosity. They are chronically teased and chased by prankster children but are almost always tossed a piece of meat at mealtimes. In earlier times of greater self-sufficiency, the winter fur of cats was used to make paintbrushes. Today, Dolpo painters such as Tenzin Norbu use sable brushes from abroad. Other domesticated animals, such as chickens and pigs, are not found in the high valleys of Dolpo, though households in lower-altitude areas of Dolpa District (e.g., Phoksumdo and the Barbung Valleys) keep them.

In subsistence pastoral systems like Dolpo’s, the primary aim, within the limits of available technology, is to produce a regular daily supply of food, rather than a marketable surplus. The number of animals a herder will cull or sell depends upon the rate of lambing, desired size of the flock, availability of labor and capital, and the male-to-female proportion in the flock. Subsistence herds are predicated upon milk production, which prolongs the lactation period and reduces reproductive rates (cf. Spooner 1973; Dahl and Hjort 1976; Helland 1980; Agrawal 1998).

The Dolpo-pa rely upon livestock animals for a wide range of products and services. Milk is the most crucial product of this pastoral system: it is processed into butter, buttermilk, yogurt, and a dry hard cheese called churpi. This cheese lasts for months and is added to stews and eaten as a snack. To make this cheese, herders ferment milk, drain it through cheesecloth, and squeeze it by hand into strips, to dry on blankets in the sun.

Milk production is highest during the seventh Tibetan month, a time of abundant forage. Most of this milk is processed into butter. A household’s herd may produce a kilogram of butter daily during the summer season, and visitors to the high pastures are regaled with every manner of milk: creamy yogurt, cottage cheese, warm milk, and Tibetan tea, rich with fresh butter. Butter is churned by hand in a variety of vessels and stored for up to a year in sheep stomachs (dead sheeps’ stomachs turned inside out), which preserves it, albeit with a rancid flavor. For pastoralists like the Dolpo-pa, butter makes tea Tibetan, consecrates religious ceremonies, moistens skin, and even conditions hair.

Small quantities of milk are collected from dzo and dri throughout the winter months; the dam (female parent) is reserved for calves only between the third and fifth Tibetan months. Goats and sheep are milked only between March and October. Women are primarily responsible for dairy production and the daily care of domestic animals.

Wool is another important product of Dolpo’s livestock. Wool is shorn during June and July to make clothing, ropes, blankets, and tents. The coarse hair of yak is woven into tents and ropes, while their soft underbelly wool is used for blankets.14 Sheep and goats produce a finer fiber than yak, and their wool is used primarily to make clothing.

Spinning wool is a constant household activity: men and women alike use wooden, hand-held drop spindles to make thread throughout the day, even as they walk. Dolpo’s women weave dense, exquisite cloth on backstrap and sitting looms; their woven handcrafts are known throughout the region for their quality and durability. Dolpo-pa earn household income by selling blankets and cummerbunds to itinerant traders (cf. Fürer-Haimendorf 1975; Fisher 1986).

Dolpo society is divided into hierarchical and hereditary groups that occupy distinct positions in public life and have different rights and duties within the community organization of production.15 People in Dolpo are interconnected not only as family, friends, and kin but are also linked by virtue of their membership in economic and social strata, which dictate significant differences in their marriage choices, tax obligations, religious affiliations and observances, and in their participation in local political processes (cf. Jest 1975; Aziz 1978). In Dolpo, social strata are important in structuring herding and livestock management.

Though Buddhist scruples forbid the killing of animals, meat is a staple of the Dolpo diet. This religious injunction is sidestepped by having lower-strata members of the community (usually blacksmiths) slaughter animals. The butcher is given the animal’s head as compensation, both for his labor and the negative spiritual accumulations of karma that accompany the act of killing. Causing stress or pain to an animal (for example, by piercing the nose of draft animals) is also considered demeritous. To avoid these kinds of ritual pollution, women never slaughter animals or perform castrations.

Male animals are culled in Dolpo during the tenth Tibetan month. Functionalist analyses in the pastoral literature of Africa emphasize the ritual sharing of meat within communities, particularly because conditions there lead to meat’s rotting quickly (cf. Dahl 1979). This may explain why, in contrast, households in Dolpo keep for themselves most of the meat they slaughter, since putrefaction is delayed by the dry cold climate of the trans-Himalaya.

Like pastoralists in other marginal environments, Dolpo’s residents also rely upon their animals to fuel their hearths. Gathering goat and cattle dung is a daily chore, a continuous harvest. Dung is a poor fuel type, though: its thick and acrid smoke causes chronic respiratory and eye diseases among the Dolpo-pa.

The quality of pastoralists’ livestock depends in large part on breeding—a set of techniques designed to ensure a quality genetic base. Selection schemes must maximize the benefits of choosing superior stock while minimizing the harms of inbreeding. In conversations with Dolpo’s herders, hardiness, body size and conformation, milk yield, number of progeny, and yield of hair were named as important characteristics for selecting breeding animals.

For male yak, a Dolpo herdsman evaluates its lineage first, and the bull itself, second. Uniformly, black yak are preferred in Dolpo, though herders often maintain other color lines in their herds. Ekvall (1968:43) writes that, among Tibetan nomads, animals are selected on the basis of observable size and, “whatever promise of spirit and tractability can be discerned in the young animal. Gelding is practiced quite early—rarely later than an animal’s second year—and may not allow a thorough testing of these capabilities.”

Stud yak are left unsheared—a symbol, perhaps, of their virility—and are said to be capable of handling up to thirty females. Breeding choices are reinforced by castrating the male animals not selected as studs. Although most experienced herders know how to castrate their animals, a community member skilled in this most delicate task often performs this job.

Inbreeding can increase as a consequence of breeding, by restricting the number of stud animals that provide genes for future generations. Inbreeding reduces reproductive capacity, growth rate, adult size, and milk production as well as increases mortality, especially among the young (cf. Li and Wiener 1995). Every household depends on the continuing reproductive viability of its herd, so there are community provisions for poorer households during breeding season: it is customary in Dolpo for wealthier villagers to loan stud animals out to households with small herds.

Due to chronic cycles of food shortage and a harsh, unforgiving climate, the mortality rate is high for newborns among Dolpo’s livestock.16 For example, the bitter winter of 1994–95 killed over three hundred yak in Tsharka Valley alone. Locals recall a herd of sixty yak perishing in one blizzard near Nangkhong; the caravanners survived by eating the leather soles of their shoes (cf. Valli and Summers 1994). Since snow, disease, and predation always threaten their herds, locals add animals to their herds during good years, as insurance against the inevitable bad years. Local attitudes toward stocking rates are framed by past experience: the living memory of hundreds of animals starving in Dolpo during the early 1960s (discussed in chapter 6) cues a mindset in which livestock herds are culled very conservatively.

The reproductive cycles of Dolpo’s livestock are manipulated to correlate closely with the availability of labor and seasonal forage. Male animals are kept away from the village for months at a time, serving as pack animals on trading trips, while females are kept close to home for dairy production. By selecting a few males as studs for breeding, and driving them down to the females’ grazing grounds, the herdsman selects bloodlines to propagate.17

Horse breeding differs somewhat from that of yak and cattle. Yak and crosses are usually bred from within a household’s herd. Horses, on the other hand, are mated through an agreement between two households. The owners of the mare and stallion agree to a modest stud fee if the mare is impregnated. Though Dolpo’s mares are often bred to local studs, the preferred match is a local mare with a stud from Tibet. This combination is said to produce a resilient colt—strong and well adapted to Dolpo, like its mother, but large in hoof and body, like its father.

There is a whole body of Tibetan literature—extant in Himalayan regions like Dolpo and Mustang—that is devoted to horse pedigree, including color and conformation as well as the shape and location of cowlicks (cf. Craig 1996). In breeding, a horse’s markings are imbued with great significance. A cowlick on the upper half of the body is good, but such a mark on the flanks, below the saddle, bodes ill and may signal a swift death for the horse’s owner.

Livestock trade is an important element of Dolpo’s economy, and its villagers turn to Tibet in order to expand their livestock herds. The rangelands of the Tibetan Plateau support large herds, often numbering more than a thousand animals. Dolpo traders augment their herds by purchasing new animals during their annual summer trading expeditions to the northern nomadic plains. The most active trade is in sheep and goats, as yak are often prohibitively expensive and livestock prices are reported to be rising in Chinese Tibet.18

Capitalizing on the reasonable terms offered by their business partners in Tibet, a trader can double his investment in sheep and goats by herding these animals for a few years on Dolpo’s range and then selling them to middle-hill farmers, especially before the Hindu festival Dasain. Celebrated for two weeks in October-November, Dasain is the largest Hindu holiday of the year in Nepal. The festival calls for the slaughter of hundreds of thousands of animals in honor of the goddess Durga. This festival provides a large and predictable annual demand for livestock and drives pastoral economies throughout Nepal.

Regionally, Dolpo is an exporter of livestock products, especially to neighboring Mustang District. Keeping yak in Mustang has become uneconomical, apparently because of deteriorating range conditions and the increasing number of mules serving as commercial pack animals.19 Nevertheless, demand for commodities such as meat, hard cheese, and butter remains high in these adjacent, culturally Tibetan areas, and there is a steady local market for those who make the long journey from Dolpo east to Mustang.

The Dolpo-pa must move with the seasons, up and down some of the most forbidding terrain in the Himalayas, in order to bring off this transformation of livestock into capital. They ply a trade in guessing the future, betting on and outwitting a mercurial and punishing climate. Livestock trade relies heavily on timeliness—making a profit may literally be a matter of days. As a commodities trader, a Dolpo herder must sell early if he anticipates that livestock supply has been met and there is a glut in the markets of Nepal’s western hills. Effort and time traveling the hard road south from Dolpo must be weighed against potential income from selling animals, even at a discounted profit—marginal utility analysis in the high Himalayas.

The ninth Tibetan month marks harvest time in Dolpo, and animals are brought down from the high pastures to villages. Dolpo-pa jokingly refer to this as the animals’ New Year’s celebration, since they can graze unhurried by herders and finally have the opportunity to mate. In each herd of ralug, a ram and billy goat are chosen as studs based on size and hardiness; these rams and billy goats service up to one hundred females each.

Synchronizing breeding with the seasons helps ensure that animals will have the greatest likelihood of emerging when forage is sufficient. Goats and sheep are the most fecund of Dolpo’s livestock, giving birth up to twice a year when they reach maturity at two years. But their offspring fare poorly, and mortality is high, if parturition is not synchronized with the availability of forage. Since the term of sheep and goats is five months, and grasses begin growth in the fourth month, breeding is timed to coincide with these plant production cycles. Dolpo herders thus practice a form of animal birth control: they bind sheep and goat studs with a prophylactic cloth, which is wrapped around the animal’s flank and prevents copulation.

Poor reproductive success and high mortality rates cap population growth within Dolpo’s herds. Culling is the time when pastoralists try to plan the size and composition of their herd for the coming year—they must not lose more animals through slaughter, depredation, and mishap than are born each year (cf. Manzardo 1984; Goldstein, Beall, and Cincotta 1990). Females who can bear young are never slaughtered in Dolpo, as their number is the first limit to herd growth. In this economy, livestock are both liquid assets and the equivalent of bank accounts.

Because livestock provide so much—food, mobility, draft labor, clothing, and status—household prosperity lies in having many livestock. Animal resources are vehicles of enduring social relations in a pastoral society. In Dolpo, marriage normally coincides with the establishment of a separate household, marked by the creation of a new livestock herd through the mechanism of bridewealth. Animals are objects of pastoral production, but they are also the means of its social reproduction: they can be fruitfully converted into symbolic and material wealth and thus play multiple roles in Dolpo (cf. Salzman and Galaty 1990).

A major goal of pastoralists in Dolpo is to balance the size of the herd with available household labor. They try to maintain an economically viable ratio of herders to animals because smaller flocks suffer from negative economies of scale and generate lower surpluses (cf. Agrawal 1998). Lacking more lucrative investments, households grow their wealth by increasing herd size. In this subsistence economy a household with large herds may not have a significantly higher standard of living than a poor one—just more insurance to meet ecological hazards. Dolpo pastoralists amass animals because so many can die from disease, poor nutrition, droughts, blizzards, or predators.

The setting of stocking rates by fiat is not an unknown practice in Central Asia: in feudal Tibet, the upper strata fixed the number of animals that were allowed on communally owned pastures (cf. Goldstein and Beall 1994). But in Dolpo, stocking-rate decisions are left to the judgment of household heads, and there is no community consultation involved when individuals buy livestock. Locals seem impassive about this seeming free-for-all. Lama Drukge of Polde village spelled it out: “One man is rich and has many sheep and goats. These sheep eat a lot of grass and everyone’s animals suffer. But if wolves attack, I will lose only a few of my animals, many of his will die. It’s like a lottery—his herd may increase quickly, but in a blizzard, he will lose more animals.”20

Beyond increasing the size of their herds, the Dolpo-pa must also maintain and care for their animals. The reliance of Dolpo’s pastoralists upon animals led to the refinement of skills integral to their livelihood. Among the most important of these skills is veterinary medicine, which is intended to force the limits of biological increase and enhance animal productivity.

Animal care in Dolpo is practiced by local doctors (called amchi) and laymen.21 As medical practitioners, amchi differentiate themselves from laymen by having completed meditation retreats and receiving initiation into the four treatises (gyu shi) that are the foundation of Tibetan medicine. But local amchi are not always available for veterinary calls. As such, householders often double as lay practitioners of veterinary medicine, treating animals using techniques they have learned by watching other herders, rather than through formal training or texts. In general, laymen veterinary treatments are limited to bleeding: the arts of making and dosing herbal medicinal compounds are left to amchi. And Dolpo is rich in useful plants: studies have found more than four hundred medicinal plant and at least sixty food species.22

Amchi play many roles in Dolpo: physician, veterinarian, and spiritual healer. They do not practice medicine full-time. The Tibetan medical tradition revolves around the tenets of Buddhism and altruism: “Since the concept of benefiting others figures prominently in motivating amchi, they cannot expect to materially prosper from their profession” (Gurung, Lama, and Aumeeruddy-Thomas 1998). In this value system, amchi collect no fixed fee for their healing works and herbs. Instead, their clients (called jindak) traditionally pay amchi in kind for their medical or veterinary services.23

Veterinary care in Dolpo deals mostly with large animals, particularly horses. It begins with animal obstetrics and continues over the course of an animal’s life to include interventions such as acupuncture and moxibustion (the application of heat to skin) (metsug), the setting of broken bones, bloodletting, and herbal remedies. Amchi use two kinds of texts—astrological and veterinary—to heal. Astrological works are consulted for the prognoses of diseases and to ascertain auspicious times for veterinary interventions such as castrations. More often than not, the veterinary texts that an amchi owns function less as reference works than as symbols of legitimacy, establishing the credentials and lineage of an amchi.24 Simply possessing these texts gives amchi a measure of authority to heal, even though individual practioners’ skills are more often than not the product of practical experience and oral tradition, rather than textually based knowledge (Craig 1996).

Lineages of medical knowledge are passed down patrilineally and by regional authorities. Many amchi in Dolpo trace their education to a Tibetan refugee who settled there during the 1960s and taught medical aspirants for more than twenty years. Kagar Rinpoche (see rinpoche), of the Tarap Valley, was a widely respected authority on medicine during the last half of the twentieth century and taught many of the amchi still practicing in Dolpo. Relations between the central institutions of Tibetan medicine and rural practitioners, especially since the Tibetan diaspora, are characterized by dynamic and international movements of cultural, symbolic, and material capital.25 Today, in a historical reverse migration of knowledge, Dolpo amchi find themselves treating patients not only in their own villages but also caring for the nomads and their animals across the border in Tibet.26

The most common livestock afflictions in Dolpo are intestinal and respiratory disorders,27 but Dolpo’s herders employ a variety of methods to keep their animals healthy. In the Tibetan medical tradition, moxibustion is believed to heal broken energy channels, decrease edema, and lower the possibility of infection (cf. Craig 1997). Amchi cauterize pressure points with a heated rod for lameness, bone fractures, and to prevent communicable diseases (cf. Dell’Angelo 1984; Heffernan 1997). Among pack animals, broken bones and lameness are all too common—the occupational hazards of heavy loads and treading treacherous trails. Broken bones are set with splints and wrapped with a poultice of herbs. In the event of lameness, caused by swelling where hoof meets flesh, a red-hot rod is seared into the center of inflammation. Wild animal bites, skin infections, saddle sores, and abscesses may be healed by applying a circle of “fire” points around the wound.

Bloodletting is a common treatment for fever, swellings, and certain digestive conditions in the Tibetan medical system. The object is to remove impure blood and cleanse veins. The king of Lo Monthang, a renowned veterinarian, has a large herd of horses and lets their blood each spring before they are moved to the high summer grazing grounds. The horses’ blood is mixed with grain and fed to the animals, which is said to bestow renewed strength and vitality. A small, pointed metal awl (tsakpu) is used to pierce an animal beneath its tail when treating lower intestinal abnormalities, said to be caused by a cold stomach. Stimulating blood flow to this region directs healing energy to it; bleeding is also practiced on abscesses of mouth and nostrils.

In the Tibetan tradition, healing animals entails not only external and internal medicine but also spiritual remedies (cf. Dell’Angelo 1984; Heffernan 1997; Craig 1997). Veterinary treatments are designed both for the body (through physical interventions) and the spirit (through the use of chants and rituals). A household may, therefore, call for a divination (mo) to diagnose sick animals. The amchi may act as a medium and cast dice to determine the cause and appropriate treatment for afflictions. These divinations can reveal, for example, that a disease was caused when a family member offended a local deity by polluting a water source.

Spiritual forces govern many daily activities, including livestock management, and may help or obstruct human affairs. As such, local explanations for the causes of ailments range widely, from the supernatural to the quite natural. Some animal illnesses are said to be caused by poor quality fodder and bad water, while others result from negative encounters with the spirit world. Illnesses may enter an animal or person through openings in the body (i.e., eyes, ears, nose, mouth, anus, vagina, top of head). Thus, as Jest (1975:152) observed in Dolpo, “to protect the herds from accidents and take care of them is not enough. The herder must also call upon a lama.”

Chanting and exorcism rituals may be prescribed to enjoin malignant forces to leave a sick animal or person. In the Tibetan tradition, chants are the heart of all healing, human and animal (cf. Dell’Angelo 1984; Heffernan 1997). These prayers are said to distill the healing presence of the Buddha. Some of these incantations are eminently practical: for example, there are mantras to increase the fecundity of cattle and ones to calm animals that kick when they are milked.28

Land management practices are embedded in faith and ritual: religious beliefs and values play a significant role in shaping individual and community views of agriculture and grazing practices (cf. O’Rourke 1986; Rai and Thapa 1993). Dolpo’s landscape possesses supernatural significance for its residents, and economic activities such as farming and livestock husbandry serve not only as means of subsistence but also as forms of participation in religious life (cf. Karan 1976; Crook 1994). Dolpo’s villagers have complex beliefs and religious practices that signify and mediate their relationship with the spiritual world. Spiritual intervention in Dolpo is most often sought for the basics—to secure food, cure illness, and avert danger.

The repertoire of an amchi includes performing ceremonial exorcisms. Texts are recited and mantras chanted to entice offending spirits into torma, offerings made of barley flour, which are often molded into the likeness of a livestock animal. Food, liquor, and beer are offered to trick the spirit into possessing this sacrificial effigy. After the spirit is enticed into the figure, it is carried away and destroyed outside the settlement, cleansing the community of harmful spirits. Thus, anthropologist David Snellgrove observed that in Dolpo, “bargaining plays as important part in the religious life as it does in everyday buying and selling” (Snellgrove 1967[1992]:15).

Dolpo’s religious rituals also address urgent pastoral concerns, like protection of the caravans as they make their yearly exodus across the Himalayas.29 Before the Dolpo-pa leave for any lengthy trade expedition, village priests make the rounds from house to house, molding torma, chanting prayers, and calling down the blessings of village and household deities. The relationship between herders and their livestock is an intimate one. After all, households are built on these animals, some of which serve their masters for twenty years.

Not only are livestock animals a means of subsistence and symbols of wealth, they are also linked to the spiritual well-being of Dolpo households. In a ritual called kang-tso, livestock play an important part. Village lamas mold yak and sheep torma from barley and beer, and ritually infuse them with blessings by reciting prayers. At the end of two days’ rites, the effigies are placed on the seat of the deity on the roof of the house and offered up to high-flying choughs, the loftiest of all birds. Village lamas blow horns made of bone, and barley flour is tossed high, like confetti, into the sky. In another ritual honoring animals, herds are gathered at the end of the Tibetan year to be daubed with water dyed red, an auspicious color in Tibetan Buddhism. The spine, horns, forehead, and flanks of a household’s yak are decorated and village lamas will consecrate the animals by touching a statue or holy object to their heads.30

In Tibetan tradition, livestock can also help their owners to gain religious merit and, sometimes, avert tragedy. In a ritual called tse thar, a yak is dedicated to the gods and set free after the reading of a text.31 Given how valuable animals are in Dolpo (even at the end of their usefulness), these important ceremonies are performed only in times of crisis—when illness befalls a family member, for example, desperate measures are in order. A yak is ceremoniously released from domesticity and becomes lha yak (god yak). This act is said to purify karma and accrue merit. In Plato’s Symposium, Eryximachus makes a comment that helps explain the motives for religious rites like these: “The sole concern of every rite of sacrifice and divination—that is to say, the means of communion between god and man—is either the preservation or the repair of Love” (Hamilton and Cairns 1961:541). This gesture of piety and self-interest seems to be “an unwitting making of amends, and an acknowledgment that domestication of livestock is an infringement of natural rights as first willed by the gods” (Ekvall 1968:81).

After the liberation ceremony, an animal can never be used for human purposes and is left to wander at will. These animals move as they please, but if they follow the herd in its seasonal migrations, it is taken as a good omen. If females are dedicated, they are generally kept with the herd and milked, but not used for breeding. Liberation ceremonies are also conducted to appease offended local spirits and demons in the event of community catastrophes such as crop failures and landslides. In a land without wood, corpses are not cremated. Instead, when they die, the bodies of lha yak are cut up and offered to the vultures in sky burials—an allegorical union of heaven and earth (cf. Palmieri 1976). At Dolpo’s oldest monastery, Yang Tser Gompa, a white yak was kept there until its death. During the twelfth Tibetan month, villagers from all over Dolpo would congregate to celebrate and consecrate the yak. The holy beast, in turn, remained and ruminated.

TRADE IN DOLPO

Nepal’s northern border regions span high altitudes where agriculture and animal husbandry alone cannot support even a relatively sparse population.32 The agro-pastoralists of Dolpo must exploit brief windows of ecological opportunity that are spatially heterogeneous. This way of life is made possible not only through agriculture and animal husbandry, as outlined above, but also by trade.

At this biological, economic, and cultural frontier, the people of Dolpo long ago seized upon trade as a means of profiting from their strategic location at the intersection of the Himalayas and the Tibetan Plateau. Dolpo’s villagers traditionally acquired resources from the outside by being middlemen—climatic and cultural straddlers in the trade between farmers from the hill regions of Nepal and nomads on the arid plains of southwestern Tibet. The traders of the trans-Himalaya achieved an economy in transaction costs without roads, motorized transport, long-distance communications, or storage (cf. Chakravarty-Kaul 1998). Dolpo’s position in the “interstices of two complementary economic and ecological zones” enabled its traders to act as intermediaries in the exchange of products from the Tibetan Plateau with those of the middle hills of Nepal; thorough knowledge of routes across this difficult terrain enabled residents of these border areas to be middlemen-transporters in a highly fragmented and cross-cultural trade (cf. Fürer-Haimendorf 1975; Spengen 2000).

The trans-Himalayan region where Dolpo lies was for centuries an economically autonomous part of the world. Its location astride distinct eco-zones and near natural channels of transport allowed this region to be essentially self-sufficient (Spengen 2000). To the north of Dolpo lie the vast rangelands of the Tibetan Plateau. The plateau’s extensive land base sustains pastoral production, but its extreme climate and environment preclude cultivation. While the nomads lack grains, they live in proximity of an ancient ocean—the expansive salt flats of the Tethys Sea, an inland ocean lifted up by the subduction of the Indian subcontinent to dry upon the highest plateau in the world.

The salt flats of southwestern Tibet lie more than 150 miles north of Dolpo’s valleys. Tibetan nomads double as salt caravanners each year to supplement their incomes and secure grain supplies from Nepal. Salt is collected in a simple, time-honored manner: broad, wooden rakes scrape salt crystals into pyramid-shaped mounds, separating mineral crystals from the brine, to dry in the high plateau sun. The salt flats are said to be the dwelling place of deities. Good behavior and pure intentions are linked to the purity and supply of salt. Accordingly, strict ritual injunctions and etiquette (e.g., no adultery or foul language) guide the behavior of the nomads so deities are not offended while salt is being collected. In some parts of Tibet, salt caravanners even speak a secret “salt language” when they work the flats (cf. The Saltmen of Tibet 1996–97). It is for the fruits of these labors that the pastoralists of Dolpo travel the risky road north for trade each year, setting out to meet their trade partners and strike a bargain.

To the south of Dolpo lie the middle hills of Nepal. These areas receive up to 1,500 mm precipitation annually, and households in these villages are able to produce annual surpluses from staple crops such as corn and millet.33 The hills yield no salt, though, and both people and animals universally need this nutrient. Placed between these two production zones—Tibet and Nepal—Dolpo acts as a commodities entrepô

After planting crops during the fourth Tibetan month, the Dolpo-pa hold informal and formal meetings to coordinate their annual trading trip to Tibet. The village council sets the departure dates for the caravans, as well as the price of barley, ensuring a united front once Dolpo’s traders set out to meet their Tibetan trading partners. Individuals travel in collective family groups: typically, a trader will travel with his horse and household herd in a caravan of hundreds of yak. The economic fortunes of individual shepherds are thus substantially and unambiguously tied to the fate of the group (cf. Agrawal 1998).

The days before the caravans depart are alive with activity, nervous packing, and constant speculation on the price Dolpo goods will fetch. On the date appointed by the village council, hundreds of yak—thunder and dust!—converge upon the trail to make their way again to the western plains of Tibet. The caravan animals are grouped by hierarchy; male yak, with their heavier loads, are sent to the front of the pack, while dzo and the other animals trail behind.

A lead yak (lampa) is chosen for its strength, smarts, and ability to set the pace for the caravan. This yak is consecrated in a ceremony before the expedition. Flags are sewn into its mane and, from then on, it carries a brightly colored prayer banner imprinted with Buddhist prayers. This blessed creature is believed to ward off the troublesome, wayward spirits one encounters on journeys. A herder may also choose a yak from his herd to represent his protective deity. He honors this yak by giving it lighter loads to carry—truly a sacrifice in such a demanding land.

The organization of caravans during annual movements is an example of how Dolpo’s communities solve problems of collective action and gain access to spatially heterogeneous resources (cf. Agrawal 1998). In a typical caravan, a group of men from households related by kinship or long association will travel together for weeks.34 The caravanners migrate as a collective, sharing food and the demanding work equally, moving the herds as a team. Only as a group can shepherds undertake the level of protection required to keep livestock and trade goods safe. The men work in concert, herding others’ animals just as carefully as their own. Everyone harnesses and saddles their own animals, but the atmosphere is one of constant cooperation, of friends sharing a long hard road. The younger men shoulder the tough physical chores of trail life such as hauling water and chasing stray animals. In these joint migrations, the authority of elder caravanners is automatically deferred to, a function of their accumulated experience, family lineage, herd size, and local customs.35 Thus, senior members of the caravan decide which trail to take, where to cross a river, and when to stop.

The grain-salt exchange cycle involves more than just the shuttling of goods between production centers: social relationships sustain these exchanges and are integral to the cultural landscape of Dolpo (cf. Fisher 1986). The most important economic and cultural relationship of exchange is that of the netsang. Literally translated as “nesting place,” netsang are business partners and a fictive family with whom one exchanges goods on favorable terms.36 Each household of Dolpo has netsang partners in virtually every village of the district, providing a reliable economic network in the risky world of commodities trade, as well as a hearth and home while traveling in this often harsh land.

Netsang share a codependent lifestyle—the basic human need for salt and grains of the earth.37 A netsang relationship is created by oral agreement between two partners and is usually sealed with a communal feast. These partners agree to trade with one another on preferential terms and form a patrilineal economic contract between families that may last for generations. The netsang system is a code of honor built on trade and territory, but ultimately the basis for the relationship is mutual profit—equal partners exchanging goods. Reciprocity is built upon the expectation that a return of benefit will be forthcoming in the future (cf. Crook 1994).

The Dolpo way of life is built upon institutions of reciprocity that tie nomadic grazing to sedentary cultivation, each sustaining the other. These instruments of mutual adjustment between herders and cultivators insure against seasonal risks and prepare against uncertainty at different elevations. Interethnic clan relationships are quite typical of pastoral nomads who subsist in marginal environments. They manifest as economic relief in times of stress and are integrated into wide-spun systems of alliance and mutual help (cf. Manzardo 1976, 1977; Baxter 1989; Chakravarty-Kaul 1998). Many pastoral groups maintain ritual and social relationships across ethnic boundaries and make use of these ascriptive but noncontractual relationships—especially in hard times, as we shall see in the case of Dolpo after 1960.

The diversity of livelihood strategies pursued in Dolpo helps reduce risk in a marginal environment, and livestock are integral to each phase of the yearly production cycle. Dolpo’s agropastoralists have developed a complex system of resource exploitation supported by reciprocal economic and social relationships. This system of pastoral production relies on mobility, political and economic autonomy, and flexible borders—the very elements of life in Dolpo that would change most in the second half of the twentieth century.