CHAPTER 6

Soldiers, Officers, Leadership and Discipline

Soon after beginning an appraisal of the ‘Great War’ references will be found critical of the British military organisation accused to some greater or lesser degree of compounding the difficulties of fighting the German Army by perpetuating the ‘class’ system. Separating worthy rankers from officers of dubious merit based only on such criteria as school attended, family background, title, estate or the old favourite, contacts in the ‘establishment’. Any attempt to argue that the officers of the regular army prior to the 1914 war were representative of the social structure of the nation would be nonsense, it was not; but as so often in this expedition through the jungle of social myth, all is not as it seems.

As recorded in an earlier section, at the time of the 1801 census from a total population in Britain, the army and militia amounted to a few hundred short of 200,000 from a population of close on eleven million, 1.7%, or thereabouts. Immediately prior to the outbreak of the 1914—18 war the regular army and Territorial Forces totaled half a million from a population over forty-five million 0.14%. These figures can be used to support various contentions, my offering is one culled from the experience of commercial life, simply put it is that any organisation not subject to the pressure of competition will continue to practice its trade in ways with which it is comfortable and meets the demands of the consumer. In this case the consumer was the British government, a customer who was delighted to spend as little as possible on the army or its reform, reforms cost money, always. Defence of the realm was left to the Royal Navy, look at all those lovely big ships the nation provided. The army was marginalised and therefore continued to recruit its soldiers from the dispossessed, the rejects of the population, when the requirements of the new industrial society had been satisfied. Officers came as they had for generations from the nation’s gentry, some sons of the newly affluent portion of the commercial and industrial community and from the ranks. For the very simple reason that it had no requirement to change, it could do the job asked of it, in ways found successful in the past. Is this a further example of the defects of a policy that left continental wars to the continentals, until it was too late, almost?

We do have to adjust our focus as well and recall that in the way the British Army was integrated with the social structure of the nation, the army reflected society and attitude; it did not set the pattern. This, in case you wondered, was quite the opposite of the situation that prevailed in Prussian dominated Germany. In the newly created Germany, post 1871, the Prussian Junker style of military attitudes dominated the scene. Young boys and adolescents of the aristocratic families of Prussia and other German states were processed through a network of military schools and academies to supply the officers to meet the needs of the large conscript army. The badge of status for a young cadet officer in the Prussian tradition was the duelling scar, the more visible the better, not a pretty sight. The German Army in the Prussian tradition occupied a position of privilege in the government of the nation, answerable to the Kaiser. Let the elected representatives of the Reichstag think what they like, the army and navy were the personal fiefdom of the Kaiser. For the less privileged men of the nation, there was conscription, the obligation for a majority of each age year to undertake a fixed period of military training of two years, followed by a continuing liability to service in one of the reserves until the age of fifty-five. France was a republic and should have been more egalitarian, but ‘L’Affhire Dreyfus̱ suggests all was not as it should have been. As for Russians and the Austro Hungarians each of these nations had forgotten more about class distinction than the British ever contemplated.

Poor Britain and her army, castigated again as the source of an alleged social injustice when the nations that got Europe into the mess and then lost the bet, had even more reactionary habits, such an embarrassment never gets a mention. If you have a case to argue then accept that there are two sides, at least, to the considerations.

On the issue of ‘class’ and its place in the events leading up to and during the Great War, this is another minefield of opinion and myth that will explode in the face of the amateur commentator, usually from most unexpected circumstances. Let me demonstrate. The Industrial Revolution created many things; the ‘piece de resistance’ of the drama was the introduction of the unique and modernising railway system that dated from the opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway in 1829. This was the cutting edge technology of the day. Not an improvement on existing ideas, as for example in the mechanisation of the textile industry. Railways powered by steam engines were wholly new as a means of transportation on land. It was the creation of inspired men such as; the Stephensons, father George and son Robert, Brunel, Crampton, Gooch, Hawthorne and many others. An industry ready to accept the talents of the entrepreneur and the inspired practical men who became the engineers, organisers and controllers; social class and parentage were not an influence, achievement was the key to success. Indeed three General Managers7 of the GWR in succession, Potter, Aldington and Pole between 1911 and 1932, each began their career as junior station clerks aged fourteen years. The industry had achieved a life span of eighty-five years only, when war commenced. Yet we find in an account of the operation of the GWR’s Swindon works employing 14,000 people that a fourteen-year-old year old boy joining the workforce as an apprentice would be allocated to a trade based on the trade of his father. If Dad was a skilled craftsman, then the son could follow in his footsteps. If, though, Dad was lower in the food chain, a son of his would be trained for a more ordinary job. Why I ask myself, in a new industry such as railways, owing nothing to the past did the old bogy of ‘class’ find its way into the affairs of the railways. Was there within the cultural ethos of the British, a predisposition to accept a hierarchy in society? A replacement perhaps for the Norman feudal system of administration that collapsed in England in the fourteenth century following the outbreak of plague, the Black Death, that forced landowners into paying wages to labour recruited at annual hiring fairs.

Having made the initial point we now need to look at what in general terms are the roles of the players on the field of battle, the profession of arms including the exercise of command. The British Army has numerous precepts by which it distils the essence of its skills, some are quite unrepeatable and these we will avoid.

What the army could not do in 1914 was to reinvent the wheel and develop a new approach to the command structure, there was no time. The barbarians were at the gates. Wilhelm II, despite being cousin to George V, the reigning King of Britain, would not get back in his box for a couple of years to enable the future ambitions of social scientists to be realised. Willie was playing for real and playing to win in August 1914.

Now to move on; in the list of precepts underlying all officers’ training is the dictum that soldiers win battles, generals lose wars. Direct and to the point, Tommy Atkins is not to blame because you as the commander get it wrong, whatever ‘it’ may be. Secondly, officers are responsible for leadership, warrant and non commissioned officers are responsible for discipline. For confirmation of this distinction ask anyone who has faced the ferocious attention to detail of a Drill Sergeant from one of the Regiments of Foot Guards when a major event is in preparation.

To explain the subtle distinction in the relationship between these two aspects of army life another diversion is needed. The issue of ‘orders’ and their place in the conduct of affairs need some explanation. There are clear procedures for issuing the instructions to officers and other ranks. At the time under consideration there were variations of practice in different units but the intention was identical. To take an example from the campaign experience to which the British Army was well accustomed, in this case a battalion, 2nd Green Howards (19th Foot), in the North West provinces of India, now part of Pakistan, in 1936. The column reaches the objective for the day’s march, halts and makes camp with all round defences, just as the Roman Army did. Within a few minutes the company commanders will receive a message, brief and to the point; COs (lieutenant colonel) order group, 17.00hrs I.O. and T‘pt officer to attend, no move before 04.30 hrs. The company commanders, majors, will in turn straightaway issue their own warning order company ‘O’ group at 17.45 hrs, no move before 04.30hrs.

These simple instructions tell all concerned that the battalion will be continuing to move and has about twelve hours to clean weapons, refuel transport or alternatively feed the animals of the pack train, eat, sleep and pack up for the next stage of the expedition. The instructions for the following day will be brisk and to the point, situation, objective for the operation, axis of advance, disposition of forces, command and communications procedures, attachments and detachments and all the necessary minutiae to accomplish the task set for the formation. The company commanders then at their own ‘O’ groups pass on the information to their own team of officers, each in turn giving appropriate orders to the sub units of their company.

The army has by this procedure given orders to the officers and men which have the authority of military law. To disobey or fail to undertake an instruction given at such proceedings is an offence under military law for which the consequences following conviction by court martial can be extremely severe. There is then a second communication system through the battalion. This is how it works, after the colonel’s ‘O’ group the Regimental Sergeant Major (RSM) will be told by the CO of the substance of the following day’s operation. The CO may well then go on to say to the RSM something along these lines, ”Mr Green some of the field craft looked slipshod today, have a word with your sarn’t majors will you and get them to work with the sarnt’s and section corporals to get a grip on the slackers, officers can’t be everywhere you know and I will not accept casualties if the cause is careless soldiering. Also, keep your eye open for the good corporals and encourage them. If this chap Hitler goes on as he is doing now, we shall be back in France again and you know that means we shall need all the well trained NCOs we can lay our hands on.”

The task has been set, orders given and the need for discipline reinforced. Nowhere in a conventional manual on management theory will you find a similar system, but it works. All the above is a possible scenario and is much abbreviated, but the outline is a valid description of how things were organised. Although the events above were after the Great War the model is relevant to the discussion. The officers did one part of the task, the warrant and non commissioned officers undertook the second portion of the responsibilities and together the army fulfilled its role. There is a continual undercurrent of criticism directed at the army that went to war in 1914 to the effect that it would have been better ‘managed’ if more ‘other ranks’ had become officers. I have great doubts about this proposition; a soldier who rose through the ranks to warrant officer became a person of significant consequence in his unit whose experience and opinion is recognised by his officers: to transpose him on promotion, to that of a junior officer in a different unit, is a significant cultural shock. Junior officers aged between nineteen and twenty-four are needed in units for their enthusiasm, daring and sense of adventure, that is what many young men are good at and soldiers expect it of them. A warrant officer of the time would have been at least thirty years old and out of his depth as a carefree spirit, looking for trouble.

The core of the difference between the methods of the army and civilian activities, finds expression and emphasis in the expression ‘The Military Imperative’; there is no room for compromise when the order is given in terms such as: “The battalion will advance and capture point 142 by 08.00hrs on 12 February.” That is the task for the unit within the overall operation. The objective will be achieved, casualties are a secondary consideration.

After the confusion of the first few weeks of the war, the army had to make emergency arrangements for the recruitment of officers and NCOs. Reservists reporting after the first few weeks, usually when they reached Britain from some distant part of the world, were combed for talent; the Officer Cadet Training Units of universities, the territorial and special reserve battalions, all had to give up valuable trained or part trained men to fill the ranks in France as well as supplying the cadre needed to train the units of Kitchener’s new armies. The dilemma remained as ever when resources are scarce, do you use a good sergeant as a sergeant major, or promote him to be an officer and accept that he must be retrained to do his new role adequately before he is of use to the organisation. This is another example of the penalty that the nation paid for running its army at a minimum manning level. Pragmatic solution to the problem, as practiced, promote the man to sergeant major and tell him that if he makes a good job of training the new recruits and his junior NCOs he will be given the opportunity for promotion to commissioned rank which as I have commented above was not always an easy transition.

To restate the situation in the decades prior to August 1914, the army had not sought recruits with education; it took what it could get and then trained the men to be soldiers of outstanding quality. After twelve or so years in the ranks, a worthwhile soldier could be suitable for promotion to warrant officer rank and capable of maintaining the discipline of his company. Such a soldier in his progress through the ranks will have become a complete expert in the minutiae of fighting, no detail of surviving under fire and giving the enemy a hard time will have been too small to have escaped his attention. All this skill will have been used to train the soldiers who are his responsibility in a regular unit. In a similar manner a subaltern joining from Sandhurst (Royal Military Academy) would, by the time he was thirty-two, have gained the experience to command a company. An officer suited to this level of responsibility would have acquired the skills to control the tactical operations of his command, understand the role of artillery fire control, field engineering, staff work to feed and supply his men and more besides. Most important of all he will have acquired the skill to put himself in the place of the enemy and therefore develop his tactics to defeat the foe.

Whatever the armchair experts might think officers have a different role to the warrant and NCO ranks, their tasks are though, mutually dependent. No wise officer ignores the advice of a good sergeant major. The impression of so many of the accounts and commentaries on the events of the Great War is that the authors do not want to understand the complexity of fighting a high intensity conflict in the conditions and on the terms presented to the British Army in August 1914 and lasting until November 1918. That little imp of mischief that sits on my shoulder can imagine such veterans of the graduate school of second guessers meeting Caesar in the afterlife and giving him a hard time for defective operations during the Gallic Wars, based on at most one reading, in translation from the original Latin, of the historic literary account of that campaign.

It is difficult to be brief on the social implications of the situation in which the army found itself in August. Suddenly, not only was it recruiting huge numbers from traditional sources and was shocked at the condition of the health and physique of many, it was also taking recruits into the ranks; men who were from the professional, commercial and industrial resources of the nation. The motives and experiences of this second cohort of recruits being as different as chalk from cheese by comparison with traditional recruits, to both the army and this innovative group of recruits there was a profound culture shock, which when you think about it should surprise nobody.

The contrasting roles and attitudes of the officers and the other ranks leads conveniently into one of the other more regular complaints, in particular, generals, of whom a criticism is voiced that such senior officers were never seen by the other ranks; therefore could not understand the conditions in which they were expected to serve. Hmmm, from my small experience, the mere suggestion to Thomas Atkins that a general is to make a visit to the unit was enough to see the doctor inundated with complaints needing immediate treatment, the applications for training courses would soar, as also would the leave requests. In other words, for soldiers to complain that they had not seen the general recently was a pretty uncommon event.

Digressing again, but briefly, to the reaction of Mr. Atkins on learning of the general’s intention, the comments that would flow around the dug outs, canteen and billets would all have the same theme. For example; ”Bleeding ’ell Chalky ’ave yer seen part one’s [orders], the bloody general’s doing annuver visit, annuver bloody quarter guard, out of me scratcher [bed] at five o’ bleeding clock, an’ no ‘ot water from the cooks fer shavin’ an’ more bull fer us in the ranks.” The visits of senior officers were not events greeted with unalloyed enthusiasm by Mr Atkins, believe me.

The diary of Capt. F. C. Hitchcock, M.C. 2nd Battalion the Leinster Regiment, 29th Division is a useful point of reference here. The earliest part of his diary covers the period from the middle of May 1915 to early November 1915, the first of his three tours of duty in France, when he served as a subaltern in the front line, records five formal inspections and one unscheduled visit, these in a period of about seven months by the divisional major general or the brigade general. One swallow, as they say, does not make a summer but it seems probable that this pattern of personal encouragement was used as a means to keep in touch with the front line units. Just as a reminder the divisional commander, major general, would be in overall command of twelve infantry battalions, three batteries of artillery, three field companies of engineers, plus, a cavalry detachment, service corps, ordnance and medical services and other smaller formations of specialist troops such as police, vets and the like. For each to be visited, judged, encouraged and advised on a monthly basis, together with all the other requirements of his command responsibilities sets a cracking pace for the diary. A history of the Royal Flying Corps records that prior to the Arras offensive in April 1917 Major General Hugh Trenchard, who was supposed to be confined to bed with a combination of rubella and bronchitis, flew himself, on the day prior to the attack, to visit twelve of his crucial aerial artillery spotting squadrons. I worked for a managing director who reckoned to see his depot managers, of whom there were no more than twenty, at their locations in Britain, once a year.

Taking up this point, the enormous problem with this subject is that so much is recorded it is practicable to cherry pick material to support or disprove virtually any contention. I would suggest however that a complaint by some soldiers that they never saw a general, in support of a claim by a commentator, post hoc, of poor generalship is taking things too far. As indeed is the projection of the pattern of visits in one division, to the army in France whole.

The diarist cited above, served in a battalion in one of the two wholly regular divisions in France, the other was the Guards division, provides rare insights into how the junior officers whose training and ambition was for service in the army viewed their task. As a young platoon officer he expected to know not just his own men but the remainder of the men in the company, referring to them throughout the diary using their name and the four last digits of their regimental number. In many cases he knew of their homes and families and where other relations were serving. He grieved when his men were killed or injured but without sentiment. The constant theme of his diary was the importance of the task set to beat the German enemy whose actions had caused the war, he and his troops were sharply focused on this aspect of events. The demands of the fighting are recorded and seen as part of the job. Particular distaste is recorded for the effect of the enemy’s mortars, aerial darts and the ‘minenwerffer’ (mortar). Each of these weapons having a missile with a trajectory that fell almost vertically towards the ground and therefore into a trench, which had no overhead protection. Interestingly, the account by Lieutenant (later Captain) Ernst Junger of the German Army, records the same sentiment for the mortar fire of the British. The Germans also had a serious dislike of the British ‘Mills’ bomb, hand grenade. This aversion came about because unlike the German ‘potato masher’ grenade which was a blast weapon, the Mills8 bomb, with its cast iron case which on explosion produced a nasty shower of shrapnel with a danger range of twenty yards or so (eighteen metres), when treated like a cricket ball could be thrown accurately for up to forty yards; a skill commonly available within the British Army and the imperial contingents who also served in France. The Germans, unused to the game of cricket, were at a disadvantage particularly so when combined with the long wooden handle of the ‘potato masher’. The phrase ‘it’s not cricket’, took on a whole new meaning.

It is necessary now to look with some care at the issue of discipline and military law as so often in a discussion it is usually not too long before the issues of military justice and the misconceptions of this issue surface to muddy the waters of sensible argument about military discipline. In an excursion such as this only the most cursory account can be given of the significance of ‘military’ law in the conduct of the army’s affairs, in particular to the importance of ‘orders’ to the chain of command. Not everything that is done has the authority of an ‘order’, the technical and administrative procedures by which daily affairs are organised are only orders when specified. Military law is derived from the Army Act passed by Parliament from time to time as required to introduce necessary changes. Included in the legislation is a portion which deals with the enforcement of matters of military discipline and criminal law. It is by means of the Army Act that the concept of the ‘military offence’ is introduced to the life of serving soldiers. Issues of civil law, tort, probate, divorce, etc. are not within the competence of the army’s judicial procedures, members of the military must pursue action for such matters through civil proceedings in the same way as non military personnel.

The first aspect of the authority exercised by the army that everyone should have clear in their minds is that all the requirements of common and statute law relating to criminal conduct, the whole lexicon of crime continues to apply to soldiers, non commissioned officers or officers as it does to civilian equivalents. What is different is the procedure administered under the Army Act, providing that the persons concerned are subject to military law, they are dealt with under the military disciplinary system. As a simple example any member of the army who steals from another soldier or the army itself is dealt with by the army’s system of justice. As a matter of information; there is a well established tradition within the army of ‘winning’ army property by nefarious means either from another unit or from a careless QM, the distinction here is that the acquired goods are applied to the common good of your own unit, not to an individual and the items are of no great consequence, polish, bath plugs, rifle oil were commonly sought items. This activity is not thought to be of significance to the maintenance of good discipline by the powers that be.

The situation can become complicated if, for example, there is an instance of fraud which involves both civilian and military personnel. Additionally a member of the army who commits an offence outside military jurisdiction, car crime perhaps, will unless there are unusual circumstances be dealt with by the civilian courts; though just to confuse things, military personnel driving an army vehicle on military property (an exercise range) could be the cause of a traffic accident and be dealt with by the military authorities for this matter. This just sets the scene and when there are no active hostilities to give the army something to do, great attention is paid to the minutiae of proceedings under the provisions of the Army Act and the strictures of the manual of military law.

There seems to be general acceptance by the public that providing criminal law is applied with justice, army personnel should have the same treatment as their civilian counterparts. The misunderstandings arise out of the requirement that additional responsibilities are required by those persons subject to military law. The Army Act introduces the concept of the ‘military offence’, something which has no equivalent in civilian life, obedience to orders, the military crimes of mutiny, desertion, cowardice, the casting away of arms, sleeping on sentry duty, striking a superior officer and more besides. There is then the catch all section of the Army Act; when I had something to do with these matters it was section 69. This section allows for military personnel to be charged with the offence ‘Conduct prejudicial to good order and military discipline’. A typical charge dealt with under this section, the miscreant having been identified by number, rank and name, could be phrased as follows on the charge sheet (AF [Army Form] 252): ”That on the 23rd May 1960 at 2350 hrs outside the NAAFI premises, Anglesey Lines, Catterick Camp, he did urinate on and over the dog ‘Bonzo’ the property of the Regimental Sergeant Major, using the words ‘and that goes for the both of you”. The outcome of such a grave offence when everybody had stopped laughing might not have been too serious. All these requirements are additional to the criminal law and there are penalties for those found guilty; after due process has been completed that could include trial by court martial; reprimands, imprisonment, reduction in seniority and/or rank, dismissal from the army or, until many years after the Great War, execution, usually by firing squad.

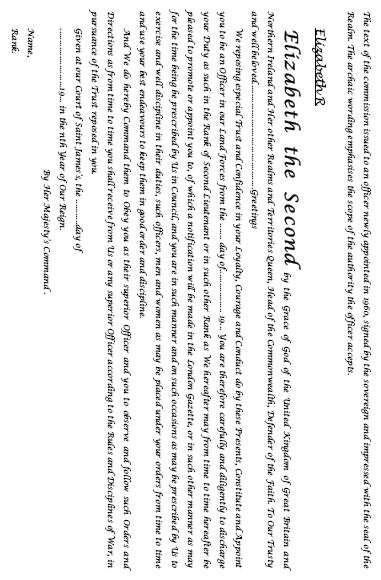

The implementation of both the conventional criminal law and these additional responsibilities of military law are dependent on the authority granted by the sovereign to the officers appointed to a commission. The wording of the sovereign’s commission specifically provides officers with the authority to require the obedience of those under their command. The soldier on enlistment takes the oath of allegiance and agrees to carry out the orders of his superiors. This is the concept of ‘original authority’, it is not unique to army officers who can only exercise this delegated responsibility within the military context and for military affairs. Matters such as; entertainments, are outside the scope of this authority, unless and until the activity affects the performance of military duties. Others to whom the sovereign grants this significant responsibility are police officers, judges, magistrates and other like officials; those in other words who have responsibility for the realm and its safety.

The system of military law administered under the provisions of the Army Act is a carefully structured system, regulated by the ‘Manual of Military Law’. It allows minor crimes to be dealt with at unit level and is specific of the maximum extent of punishment that can be imposed by unit commanders. There is no such thing as summary justice at the whim of an officer or NCO, the charge can be a whim, the outcome of due process is another matter. The authority of unit commanders to deal with more serious offences are proscribed and limited to forwarding the matter for trial by court martial. There is also provision in the proceedings at unit level allowing an accused soldier to refuse to accept the decision of his unit commander and elect for trial by court martial. A nightmare scenario for a unit adjutant is a number of ‘squaddies’ returning late to billets drunk as skunks and when apprehended and charged all the accused decide there is nothing to be lost for their misdemeanor by exercising their right for trial by court martial. Little would such miscreants appreciate that the board of a court martial would take serious exception to such time wasting and could well use their additional powers of punishment to teach them a lesson.

The inattention to the precise details of military affairs continues to lead to mistakes which have the result of perpetuating myths of arrogance of attitude by and amongst the officer class. A well known television series included an installment in which a soldier of the 1914—18 war, in full kit and uniform, within the sound of front line action is found wandering by a senior officer. According to the script he was arrested, dealt with summarily and executed by firing squad. Such a representation is a travesty, a soldier in uniform with his rifle, close to the front could not be treated as a deserter, a charge of cowardice was notoriously difficult to sustain and as he was in possession of his rifle he had not cast away his arms, the most likely charge was that ‘he was absent from his place of duty’. Another example which made me cross, and unfortunately I did not record the details of the source, was in a novel of the 1939–45 war and has an officer in 1940 reducing a sergeant in a regular battalion of an infantry regiment to the ranks on his say so. Such an action could not occur, the unit adjutant, fearful for his own reputation, would act immediately to quash any such attempt to impose summary retribution. For such punishment there must be a charge brought under the Army Act, dealt with at unit level by the commanding officer. If the commander believes a suitable punishment is beyond his powers, as would be reduction in substantive rank, a court martial must take place, a guilty verdict returned and the punishment awarded by the court including the loss or reduction of substantive rank.

In the context of the Great War, much controversy and incalculable rivers of ink and media time was utilised in a campaign of misinformation during the last twenty years around the 346 military personnel, not all soldiers, who were executed, of 3080 sentences handed down by court martial, for various crimes during the war. There are two very helpful sources of advice on this difficult subject; Gordon Corrigan in Mud, Blood and Poppycock, (Chap 8) and the essay by John Peaty (Chap 12) in the collection, Haig, edited by Brian Bond and Nigel Cave; both are good starting points, for those who have an interest in taking their knowledge further. Modern day politicians though do not understand the mood within the army of the day when the decision to carry out the death penalty was made. Casually it would appear, under media and campaigning pressure for reasons of expediency, a general pardon for those who did suffer for their crimes was granted.

The crux of the matter is that under military law all ranks of the army are obliged to obey orders. Orders are not a basis for negotiation they are the expressed command of the sovereign and there are penalties for those, who having sworn obedience, do otherwise.

This synopsis of the fabric of military affairs has to consider the issue of leadership and this is the point where I take risks of significance with any sympathy that I have accumulated with the earlier sections of this excursion through this alternative assessment of the Great War. Offering others firm opinions on the scope, style and influence of the talent, or lack of it, referred to as leadership is about as dangerous as Cardinal Wolsey telling the good King Henry VIII that Catherine of Aragon must remain his wife.

Nevertheless duty must be done, here goes. Dictionaries are quite useless, providing anodyne definitions that tread with consummate skill round the issue of what leaders and leadership achieves, so no help there. There has to be a starting point and for the purposes of this analysis consider this suggestion. Leadership is the ability of an individual to influence others to combine and cooperate in the achievement of some common purpose, and in unfavourable circumstances to use reserves of skills and ability to succeed in the common aim in ways which may be to the detriment or personal loss of an individual. The key issues that have to be addressed are the role of an individual working with a group to succeed. The defect of most considerations of this difficult aspect of life is that few, if any, who look at the subject acknowledge that situations demand different repertoires of abilities. As an extreme example of this contention consider Isambard K. Brunel, brilliant engineer, entrepreneur and leader as creator of the original Great Western Railway, accepted as such in this context simply because he had no rival, his leadership depended on his unusual combinations of talents which no one else replicated. There were though, in his personality, elements common to those we expect a leader to demonstrate: enthusiasm, determination, imagination, specialised knowledge and courage, the list goes on. The final attribute quoted is the block against which many stumble, the reckless bravado of those who lead the way into physical danger of any description is of a different character to that of the calculating risk taker of an enterprise, such as Brunel; who could have had common cause with the strategic requirements of Haig’s command.

So it was in the British Army of the Great War, the demands for reckless enthusiasm needed by the junior company officers in the trenches were not those needed by Haig as Commander in Chief. There is a difference in the roles fulfilled, generals do not belong in the front line, they get in the way. The German General of the 1939—45 conflict, Erwin Rommel, is often singled out for praise by commentators for his front line leadership in North Africa. In the accounts by German officers of the campaign there are strongly expressed views that Rommel’s frequent absence from his headquarters, partying around the Western desert, was very detrimental to the overall direction of the campaign and this, with greatly improved radio communications. Such officers do have to have the courage to stand up for their men and the units to which they belong and prevent them from being over exposed to risk, taken for granted and unfairly treated so far as training, supplies, leave, luxuries and awards are concerned. In fulfilling this role they put themselves at risk, as, although they may not be killed, they can if defeated on such matters be finished professionally, as was Lt. Gen. Horace Smith Dorrian, of whom more later.

The issue of ‘The Generals’ is at the core of most individual perceptions of the Great War and the issues arising from the conduct of the conflict; almost without exception the myths used by those who comment centre upon ‘unthinking waste of life’. Not for one moment should that generalisation go unquestioned. Already we have recognised the consequences of expecting an army of half a million, including reserves plus the part time Territorial Force to expand by a factor of ten at least, the impracticability of the tiny officer pool building this enormous new army, the quantum differences in strategic and tactical concepts and so on and soon. Yet we find criticism of generals on the grounds of their upper class style, names for example; Adrian Carton de Wiart, his family was of Belgian descent by the way, or the honours granted for past service such as Companion of the Bath (CB). If you make the comparison with the German Army there were just as many generals with funny long names, what about, ‘von Prittwitz und Graffon’(commander of the German Army on the Eastern Front), and a chest full of orders and decorations? The Prussian enemy loved nothing more than a well decorated chest, very manly. Another who should have known better, pours scorn on generals for the nicknames they attracted claiming the names given demonstrated the contempt in which the officers were held. Nicknames were part of the culture of the day, boys expected to acquire them as well as award them. This particular critic also condemned one corps commander as ‘a very stupid man’. Reading between the lines I suspect that this opinion could well be a reflection of the general’s lack of enthusiasm for the colonel’s proposals. My question is, if the good colonel was so competent, why wasn’t he at least a brigadier general at the time? Subsequently he did achieve the rank of major general. After all one of the Bradford brothers reached the rank of brigadier general at the age of twenty-five, having started the war as a lieutenant in the 2nd Battalion the Durham Light Infantry. He was killed in 1917 when on an excursion from his HQ to visit one of his units, a stray shell splinter found its mark!

Once again the critics are matching the selection of facts in support of their preconceptions. An astonishing example of this process is the quote by one historian of the comment of a staff officer, undefined by rank or function, who when viewing the battlefield of Passchendaele is reported to have said “Good lord did we send men to fight in that.” The criticism being that the remote staff had no idea what was being asked of the troops. Remember this, if you will, there were many on the staff who quite rightly did not know what was going on on the battlefield. For example an officer on the staff of the Royal Engineers, Railway Staff Corps was in France to run the railway system used by the British Army. He would have had more than enough to do with his responsibilities to be able to find time to get himself up to the front line. If this unknown officer ranks for criticism then his formation, rank and appointment ought to have been quoted.

It is worth reminding ourselves, as we follow the procession of information in this review, of one component to making a good case from an apparently confused mass of detail and material. As a concept of logic an argument must be constructed from the particular to the general. Argument should not proceed from the general to the particular.

The question of leadership as I see it, in particular for the events of the Great War, circulate round the published expectations of individuals, not what was possible in the conditions of the fighting. Some of them, opinion formers who experienced the conflict first hand, such as Blunden, Graves and Sassoon, have the authority of their experience on which to draw. Others, though, deploy arguments that rely on hearsay and selective examples to make their case, usually to dismiss the effect of the leadership exercised by the various ranks within the army, claiming as they do, that in the winning the ‘sacrifice was too great’. Their case rests on the flawed concept that lives were wasted. Such reasoning has failed to grasp the fundamental difference of this war. This difference was that winning was an ‘at all costs’ requirement. For the first time in a hundred years democracy and the independence of nations was at stake. This was no sideshow colonial war in a far off province which if unsuccessful had no significant effect on the nations of Europe; the outcome of the Great War was crucial to the way that the majority of people in Europe would live their lives in the future.

Was the concept of the leadership exercised by the British Army from 1914 to 1918 unsuited to the task? Some leaders certainly will have failed to discharge their obligations adequately but show me any organisation of equal size and complexity and there will be leaders who will be found wanting at critical moments. The difficulty is that trying to define leadership is about as easy as putting your thumb on a blob of mercury; there is nothing there when you lift your thumb. We all know what leadership is and recognise it when we see it, few if any can provide a satisfactory definition. The benefit the army derived from the network structure of ranks and leadership roles described above was that as the tasks unfolded and leaders were found wanting or lost as casualties, others exercised their judgement and initiative and filled the gaps. What is more the leadership of the British Army was an essential part of a winning team.

In the context of the foregoing paragraph there is one enigma that can never be solved now but leaves unanswered questions on which to reflect. In August 1914 the BEF comprising two corps, a total of six divisions, was on its way to France as we know. The C in C was Field Marshal Sir John French, Sir Douglas Haig commanded I Corps and a General Grierson had been given command of II Corps. As the army made its way to the front line our interfering friend Murphy made a contribution to events, Grierson died of a heart attack. A replacement had to be appointed instantly and the choice fell on Lt. Gen. Horace Smith Dorrian; a respected and experienced infantry soldier. Here was Murphy’s second chance to make a contribution to the difficulties created by the sudden change of commanders. French disliked Smith Dorrian intensely. Smith Dorrian had succeeded French in the prestigious Aldershot command and promptly revised the training systems and objectives, in particular turning the cavalry units into mounted infantry; anathema to French who was a ‘dyed in the wool’ lance and sabre cavalryman. French did not forgive and forget and Smith Dorrian in turn was known to have a fiery temper.

As the BEF engaged in the early days of fighting in France, II Corps was competently led and fought well as the pressure of the German advance became more and more acute and the French Army gave ground. II Corps was seriously exposed, Smith Dorrian recognised the danger and with a bold Nelsonian touch reinterpreted the orders of his commander, French, the C in C. II Corps then fought an effective stopping action at Le Cateau, eventually withdrawing to safety, continuing the retreat from Mons.

Field Marshal French was not a happy man but had to leave the errant Smith Dorrian in position as his actions were clearly correct. He did not survive for long however and in the spring of 1915 was transferred to Britain to take up command in East Africa. French was found wanting in due course and was replaced by Haig later in December 1915.

The issue raised by this clash of personalities, because that is what it was, is could Smith Dorrian who had proved he was a competent commander have made a successful army commander under Haig or even challenged Haig for the top slot as C in C?

The French/Smith Dorrian disagreement was a loss to the army and its officer corps which might have been corrected by some imagination. The losses to the officer corps in general revealed in the diary of the Irish Guards, 1st Battalion, records the names and ranks of those killed from the regiment. The losses of junior officers, subalterns and lieutenants as a ratio were one officer for twenty-six other ranks. The establishment ratio of a rifle company for junior officers was one to thirty other ranks. Life was 12.5‰ more dangerous for junior leaders than it was for other ranks. Officer casualties were numerically fewer than other ranks but as detailed in an earlier section less than 5‰ of a battalion’s combat strength were commissioned officers.

There is however no room for argument with the proposition that all the casualties of the Great War were an appalling and grievous loss to the wealth of the nation. As to the question of necessity my argument in this examination of events is that the Allied governments had no option but to take up arms to defend their societies. Their success depended on leadership just as much as it required materiel, finance and the achievement of soldiers to defeat the intention of the Kaiser and the German High Command.

One critic of the Passchendale offensive which was plagued by bad weather was to the effect that when the going got tough in October, Haig should have realised how unpleasant things had become for his troops and called a halt to the operation. The C in C did not have the luxury of this option; the battle had to continue until it was certain that the Germans would not launch an attack against the French lines, whilst Petain was completing the task of rebuilding the army following the mutinies after Neville’s failed spring attack. What was the alternative? Certainly there are no credible ones encountered in the literature I have seen. To sustain the operation in the face of the enemy and the conditions required leadership from the C in C, Haig, through every rank and formation, this was delivered by the men of the day.

At this point there is some value in looking briefly at the rewards for service during the Great War, some seem obvious, others more subtle. In respect of the latter category good unit commanders used the opportunity of training courses to protect and rest both officers and men from the daily effort of life at the front. Four weeks at the corps Bombing School improved the skills available to the unit and eased the strain on the soldier. Regular officers were still being processed through the promotion system and would be posted back to Britain for the appropriate courses. There were also opportunities for postings as instructors at the training schools. Both of these arrangements were rewards as well as the protection of experienced men. Then of course there was leave, local leave in France or an opportunity for a return to ‘blighty’ for home leave. The granting of leave was of course at the discretion of unit commanders but it was a right and many soldiers were able to return to their homes for a few days. Not surprisingly there were mixed feelings, the contrasts were too significant for complete adjustment to the unthreatening environment of home life. It is worth remembering that one of the complaints made by the soldiers of France who mutinied in 1917 was that leave was an illusion never in practice realised.

Britain also paid her soldiers of all ranks9, not as much as they were worth but paid they were, and, better paid than their French equivalents. There was a small group of officers who were always welcome when one of them arrived at a unit as it rested from front line action. The field cashiers who went round paying out money and cashing cheques, often at no small risk to themselves, they never had a frosty reception.

Then there was promotion, the change in rank was not always an incentive as it usually involved additional duties, but there were advantages as well not just pay. Admission to the sergeants’ mess, after life in the ranks was a respectable perk. Morale could be improved in a unit when a recognisably good soldier achieved promotion. Promotion during war time operations on the scale of the Great War are not at all straightforward but some effort must be made to put the issues on record. The regular army went to war knowing exactly who held what rank and the seniority of that person in his rank, usually by date of promotion but not always. All that had to change, rapidly, as the army expanded. Officers and other ranks of the regular army and recalled reservists had to be promoted quickly to fill vacancies created by casualties and new appointments. Now we get the outcome of making things up as you go along. An officer could be given acting rank, for example from captain to major, and go off and take on responsibilities and serve as a major and he would be employed as such as long as needed. The service in an acting rank though did not count for the purposes of seniority. The demands of the war were such that appointments above the officers’ substantive rank were virtually guaranteed. That was for the regular officer establishment including those from the pre war special reserve. Now to the temporary soldiers, officers and other ranks the whole scheme was a bit academic. Their ranks were all temporary and had no regular army seniority attached to them; so far as they were concerned, come the end of the war they were intent on leaving the army, alive and in one piece. They soldiered in the rank required and left after the war some retaining the honorary rank achieved during their war time service. Many regular soldiers were promoted several steps above their substantive rank. Major generals under war time conditions who, when the fuss died down, had to face the possibility of reversion to their regular army rank of lieutenant colonel for example. There was also an ‘ad hoc’ system of ‘local’ rank which was unpaid but required the lucky recipient to do the dirty work of the rank. That is why Corporal Lucas A. M. was discharged on expiry of his service as a member of the Territorial Forces in 1917, during a time when he with the battalion were busy in action on the front line, was on immediate recall to the colours, recommended for promotion to the same rank, but local and unpaid. He quite rightly invited those concerned to visit the taxidermist and continued his service as a private soldier. Ranks, seniority and service are not at all a straightforward subject!

Morale was also one of the essential considerations of the awards and medals system. The morale of the soldier who deserved recognition and the improvement of the unit’s self-respect by the recognition of the contribution and bravery of its members. Orders, decorations and medals in itself are an absorbing and intricate subject on which acres of print have been expended; for the purposes of this discussion brevity must be the watchword or else we shall end up with another 50,000 words. Essentially, orders are the ancient chivalric awards in their various degrees or classes awarded by the sovereign for particular and loyal service to the Crown, for the armed forces the Order of the Bath and from 1916 the Order of the British Empire, Military Division, were and remain the mark of distinction for soldiers. These marks of service are not intended to recognise acts of courage although often the service recognised contains continuous requirements for the courage of one’s convictions. Courage in the face of the enemy is recognised by the medals awarded for specific acts of gallantry. The system was regularised during the Crimean War and the pre eminent award of the Victoria Cross was instituted, until recently the only award common to all services their officers and other ranks. There were 627 VCs and two second awards, one to a medical officer and the other to a chaplain. For the army, during the war of 1914 to 1918 there was the introduction of two new awards. For officers and warrant officers the Military Cross (MC) was instituted in 1914 and for other ranks the Military Medal (MM) in 1916. These awards supplemented the Distinguished Conduct Medal (DCM) for other ranks and the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) for officers as recognition for gallantry which had been introduced after the Victoria Cross. In all for gallantry the King authorised the award to army recipients of 135,723 medals and more than 48,000 ‘mentions in dispatches’. Service on campaign was marked by campaign medals with the addition of clasps for special actions or particular years. The three common campaign medals for Western Front service were nicknamed after cartoon characters of the day, ‘Pip, Squeak and Wilfred’.

The pre eminent award was then and remains still the Victoria Cross. ‘For Valour’ was the choice of Her Majesty and the conditions of the warrant of the award have if anything since the inception of the award become more rigorously applied. The young airman who, during a flight back from Germany in 1943 in a badly damaged bomber, crawled onto the wing of the damaged plane with a fire extinguisher to deal with a fire in one of the engines was awarded the Victoria Cross. To which the uninformed, quite rightly would say “I should think so too.” Not so the awards committee of the day who expressed serious concern that the airman’s bravery was compromised by the self interest of saving his own life. The majority of the 627 awards of the VC during the Great War were posthumous; what of the remainder, the bravest of the brave? Several others died as a consequence of other actions. The award of a VC did not see the soldier treated as a special case and withdrawn from action. Of those who survived the conflict some carried on being soldiers, Gort, Freyberg and Smyth all achieved much in the 1939—45 war. Others became civilians again and made successful careers, one such was a civil engineer who won his award in the final days of the autumn advance to victory in 1918. After leaving the army he eventually established a practice as a consulting civil engineer in the Midlands. Subsequently he was knighted for his services to the construction industry. In his later life he was not always meticulous about wearing his decorations when there was an official function. A custom developed amongst those friends and colleagues who met him regularly at such events. The precaution taken by his friends was to keep their own lesser decorations in the pocket of their suit and only if the respected knight had remembered to wear his decorations would the remainder of the party find the opportunity to put their lesser medals in place on their lapels. (That anecdote was provided by the late George Marsden, served RNVR 1917/18, who was associated professionally with this holder of the VC.) Of the others they appear to have become what they had previously been, Tandy, VC, DCM, a gate keeper at the Triumph motor cycle factory, Garforth VC, War Department Policeman, another Edward Foster VC, a Refuse Collection Supervisor.

The combination of awards, campaign medals and rank enabled the old and bold soldiers to recognise quality when they saw it, the ribbons above the left breast pocket the rank and the regiment or corps told a story and provided fair warning, to those who knew how to read the code, of the discretion that ought to be exercised when dealing with someone unknown. Let me quote an example. The diary of the Medical Officer of the 2nd Battalion, (His Majesty’s 23rd of Foot), The Royal Welch Fusiliers, Captain J. C. Dunn, DSO, MC and Bar, DCM, RAMC, with the campaign medal awarded for service in South Africa during the Boer War, has been a valued source of information. The award that would attract the attention of the regulars of the Welch Fusiliers when he joined the battalion in November 1915 was the Distinguished Conduct Medal (DCM) and the South Africa ribbon. The DCM was the award for bravery for other ranks, but the good doctor was forty-one in 1915, the dates did not make sense, the reason; although qualified as a doctor, Dunn volunteered his services in South Africa as a Yeomanry Trooper, aged twenty-six in 1899. He earned his award during service in the ranks. Later in that war he took an appointment as a civilian surgeon. He would have been received with respect by all ranks of the battalion in 1915 when he joined and would have accorded equal respect to the members of the regiment for whom he was responsible. There was a subtlety in the method which is at odds with most perceptions of military interpersonal relationships, now that’s an oxymoron if ever I saw one. The old and bold soldiers of all ranks could read the ribbons on a man’s chest and at once recognise the quality of the stranger.

Another with the same pedigree was Major General G. F. Boyd C.M.G., DSO, DCM who commanded 46th Division in the last weeks of the war. He also earned his DCM in South Africa. This example illustrates another valuable lesson. General Boyd was commissioned from the ranks and must have been not only an exceptionally good soldier but also exceptionally lucky. If he commenced the war as a company officer and served in line regiments earning a DSO on the way, clearly there was never a bullet with his name on it. He was able to serve long enough without significant injury to learn the business of command and generalship, others for sure were not as lucky. He understood the military task to a degree that enabled him to lead his division to attack German positions astride the St. Quentin Canal and wrest the Riqueval Bridge from the determined enemy, an achievement of great significance in the advance to victory. Another instance that suggests that all the accusations that the British Army was in thrall to a self serving, introverted military caste was not quite the case when considered in detail. But then any respectable preconception can ‘out bid’ a decent fact whenever you like.

Finally in this section I would like to turn to the record of one family of four brothers. So far in this review of the Great War I have deliberately avoided detailed consideration of individuals and their contribution to the outcome of events, large or small. I did not know the men concerned and to become consumed with the details of individuals and their talents or defects was not the way I wished to develop my theme. I must plead your tolerance for my limited comments on some historical personalities such as Bismarck, William of Hohenzollern, Gavrilo Princip and their late Majesties Victoria and Edward VII, and some others. It was I think essential to place these and other personalities in their historical context. I make no apology for approaching these luminaries with less than due reverence.

Now to the Brothers Bradford; the family lived mainly in the North East of England, Northumberland and Durham was their home territory. The boys’ father was a mining engineer who not only worked in Britain but also abroad, he was by all accounts an extremely tough, hard and unsympathetic man, even by the standards of Victorian England. The boys’ mother was the moderating influence; the family was completed by a sister. The eldest son Thomas Andrew, was born in 1886, the second son George Nicholson, was born in 1887, followed by James Barker the third son in 1889, the youngest, Ronald Boys was born in 1889.

The eldest son Thomas had aspirations for a career in the Royal Navy but did not progress beyond the stage of cadet. In 1906 when he was twenty he was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the 4th Battalion the Durham Light Infantry (DLI). In 1914 he was OC ‘D’ Company as a captain, 1915 saw him in France at the second battle of Ypres during which he was twice mentioned in dispatches. In 1916 he was a major commanding ‘A’ company of the combined 6th /8th battalions DLI and awarded the DSO, thereafter he served as a staff officer and as an instructor.

The second son George, joined the Royal Navy as a cadet in 1902, commissioned as sub lieutenant, served on HMS Orion in 1916 at the Battle of Jutland, promoted to lieutenant commander 1917, he volunteered for duty on the Zeebrugger raid (see Chap 10) on St George’s Day 1918, awarded Victoria Cross, posthumously, gazetted 17th March 1919.

James the third son joined the Northumberland Hussars in 1913 and went to France with the BEF in 1914, commissioned in 1915 as a subaltern in the 18th Battalion of the DLI he became a specialist bombing officer, awarded the MC, he was wounded and died on 14th May 1917.

Finally there was Ronald who also first joined the DLI in 1910 as a territorial soldier. In 1911 he transferred to the Special Reserve before being granted a regular commission in the DLI, 2nd Battalion, in 1914 he also went with the BEF to France. In 1914 he was mentioned in dispatches, in 1915 he was a captain with temporary rank in the appointment of adjutant, first with the 7th and then with the 6th Battalions of the DLI. He then took a staff appointment as brigade major before becoming second in command (2i/c) of the 9th Battalion as a major before promotion as lieutenant colonel (acting rank) as he took emergency command of the combined 6th and 9th Battalion of the DLI. On 25th November 1916 he was gazetted with the award of the Victoria Cross. In 1917 he was promoted brigadier general commanding 186 Infantry Brigade at the age of twenty-five. He was killed on 30th November 1917 when undertaking one of his regular excursions to visit one of his units. He had also been awarded the MC during his service but I have no note of the date.

Four young men, two Victoria Crosses, one Distinguished Service Order, two Military Crosses, a clutch of Mentions and one survivor.

Footnote; the most decorated non commissioned soldier in the British forces was a stretcher bearer, Lance Corporal Coltman VC, DCM and Bar, MM and Bar, 1 /6th North Staffordshire Regt.

Dedication.

E. H. Robinson. Esq. DSO, MC and bar, MA.

This portion of the expedition is dedicated to E. H. Robinson. Esq., Headmaster, Moseley Grammar School, Birmingham, 1923–55, previously Major, King’s Shropshire Light Infantry; a Kitchener soldier.