CHAPTER 9

Casualties; Cause and Effect

Note. This difficult subject is dealt with in two sections of one chapter, the first part more descriptive and the second part an attempt at a statistical comparison. Beware, the figures used in the two sections are not directly comparable, the first section uses information quoted by other writers whose sources if provided are cited. The analysis section is a comparison of the statistics quoted in the tabulation; the two sets of figures do not match in detail.

No one who has ambitions to argue a case about the Great War can avoid the necessity of considering the implications of the human cost of the losses incurred by the combatant armies during the fifty-one months of conflict. Before offering for consideration my comments, there are some very basic aspects of the conflict that need to be evaluated, they form a constant background to any discussion of this aspect of the war.

1. War and war like operations will cause casualties; they are the natural outcome of fighting. Once Europe set course for war in summer 1914, men and some women would be killed and injured, both as military and civilian casualties. That was the only certainty offered by events from August 1914.

2. This eruption of violence, beginning in 1914, was the most ferocious and widespread European war ever, unique in numerous ways for which there was no prior experience, militarily, technologically or politically within the social structures of the nations who became embroiled in the war.

3. The technology of weapons had advanced dramatically in a fifty-year period and had moved in favour of the defender. Improvements to artillery including the ammunition used, infantry equipped with breech loading rifles and automatic machine guns dominated the battlefield. Airpower was a wholly new factor to be added to the equation of war. Remember if you will that the first manned flight using an internal combustion engine was made by the Wright Brothers only eleven years before the war began. Radio and telecommunications were rudimentary; Marconi’s first transatlantic signal was made in 1900. Add to the list as you will.

4. British society and its leadership had no conception of the scope and influence that ‘all out’ total war would require of the emotional stamina of the nation. Why should the nation understand? It had never happened before to the British nation; Napoleon’s war a hundred years previously had only used Britain’s professional soldiers. There had been no ‘levee en masse’ taking conscripts from their home to fight a foreign war.

5. There were no established tactical doctrines to which commanders could refer when facing an action. Indeed the opening phases of the campaign caused high casualties for both the German and French Armies. The various authorities available to the amateur researcher are surprisingly coy about the losses sustained, the nearest I have come across refers vaguely to the French suffering more than 306,000 casualties and officer losses of 20% of the regular establishment, in the opening weeks of the conflict. The figure for the German forces was 241,000. The British losses were numerically much lower, a direct consequences of the much smaller number of soldiers who fought in the first five months of the war.

Once the light of 1914 is substituted for the undiminished glare of hindsight the statistics of casualties can be approached in a less scornful frame of mind. Before any critic now condemns the decisions of military professionals who undertook command responsibilities it is essential that they offer proof that an alternative could have achieved an equivalent or better result. Better in so far as, the conflict was shortened, the material cost reduced, the casualties fewer, the grief of the population relieved and the outcome, so far as the achievement of a military and political solution at least would be, was satisfactory for the injured nations, as the eventual Versailles treaty of 1919. That is the frame into which the counter arguments must fit. The difficulty faced by both critics and protagonists is that there can be no rerun of events to prove a point, all is conjecture.

There are yet further complications to dealing with this most difficult aspect of the Great War. The world has become used to statements such as, ‘more than 55,000 casualties on the first day of the Somme’. Later we shall look in more detail at the casual way in which figures such as this have been used to support a partisan assumption of failure with no attempt to fit the action to the demands and the outcome. Perhaps it was a disaster; the mere repetition of a statistic, however, it is not of itself, an argument.

The discussion of overall casualty numbers including killed, wounded and captured presents two immediate problems. The casualty reporting procedure for the three main players on the Western Front were not directly comparable. This means that if an attempt is made to compare the quality of command based on casualties the prime measure does not translate between the armies. On the face of it a dispassionate commentator would expect there to be little or no issue on the number of combatants killed or wounded in the armies of Britain, France or Germany, such is not the case apparently. John Terraine in his work The Smoke and the Fire Chap III, sets out information from official and academic sources from which the inference has to be that there is uncertainty as to the total number of casualties in the numbers quoted. The French information varies between 4.38 million and 6.0 million19 including a total of dead that suggest that 1.385 million soldiers in the French Army were killed, but injured were somewhere between 3.0 million and 4.615 million. It is also far from clear if the total for the French Army includes the number of soldiers from the overseas territories such as Algeria.

The numbers for British casualties, also have some uncertainty, the official history quotes a total of 996,000 killed, including troops of the imperial contingents. These totals are though for all losses throughout the world where the British Armies fought. Two established historians of the Great War, John Terraine and Richard Holmes, use with confidence a figure of 750,000 for British soldiers killed on the Western Front. Soldiers from imperial contingents killed on the Western Front totalled 135,000, a total for the armies under British command of 885,000. Additionally there are those who died through disease, accidents and in the case of the Chinese labour corps, those murdered by their fellows for one reason or another. The official statistics for British dead, published by HMSO in 1919, give the following totals for the Western Front; officers 41,846, other ranks 661,960, a total of 703,806 to which must be added the soldiers from the imperial contingents, see above. This later figure seems too low, and it is more respectable to argue the case for the British Army based on the figure of Terraine and Holmes. The German information is more difficult to appraise. The original information was that the German dead totalled 1.8 million, official German sources now quote a figure of 2.037 million some of which occurred on the Russian Front, leaving a mysterious classification ‘Missing and Prisoners’ of more than a million.

Adjusting this figure to allow for the increase in the numbers killed still leave a total of more than 800,000. Britain returns fewer than 200,000 under this heading.

The paragraphs above are there to illustrate the argument that casualties were not unique to the forces under British command. It is therefore remarkable to the amateur that an author, Robin Cox, publishing in association with the Imperial War Museum, should in writing of Field Marshal Haig, make the unqualified comment that the British forces under his command suffered 750,000 ‘casualties’ in 1916/17. The argument is tendentious; no counterbalancing information is given for other forces on the Western Front. For example the French and German forces together incurred 750,000 casualties in the battle for Verdun.

There is an apparent anxiety amongst those who write the populist version of these historic events to ignore not only the essentials of balanced analysis, the omissions unfortunately seem to have become the accepted version, reinforcing the errors and distorting what ought to be a matter of historical accuracy.

The second issue that arises is counting the wounded. As a starting point how did the reporting procedure operate in the British Army, and the imperial contingents. To recapitulate for a moment, once the lessons of the Crimean War were assessed and the necessary reforms introduced it was realised that the recovery of a trained soldier from injury was a much more economical way to secure replacements troops. The British Army reformed the Army Medical Corps, Royal (RAMC) from 1898, and its medical services with a network of treatment stations with doctors and trained medical orderlies. The Regimental Aid Post (RAP) was the first treatment station, from which soldiers were passed on through Advanced Dressing Stations to Casualty Clearing Stations, the injured then moved on to Field Hospitals or Base Hospitals; there were various categories, according to the treatment needed. The most seriously wounded were evacuated to hospitals in the Britain, a wound needing treatment at such an establishment was known as a ‘Blighty One’. To complement the medical services there was an ambulance service using dedicated vehicles, trains, ships and even barges on inland waterways; all under the protection of the ‘Red Cross’.

As is common in the British Army, if Tommy Atkins is to receive a benefit such as improved treatment for wounds, there is a price to pay. Once the new improved medical facilities were installed it became a military offence not to report an injury, however slight. This was done as a precaution to avoid the contamination of wounds which could lead to blood poisoning and gangrene, well before the days of antibiotics. Following the ‘law of unexpected consequences’ this meant that for the British Army and the imperial contingents numbers of wounded on the Western Front reported by the British included those whose injuries were minor, perhaps requiring little more than cleaning and stitches. Also there were soldiers, officers and men, who had been wounded previously and after recovery returned to duty, sometimes within a few days of the injury, under the abbreviated label, D&D Ᾱ dressing and duties. The effect of this system of counting all wounds, however slight, was to emphasise the total without discrimination. As an example Bernard Freyberg who won his VC in France and commanded the New Zealand forces in the 1939–45 had numerous wounds as a consequence of his service in the Great War. He was required to strip naked by Winston Churchill during one meeting when he was a general to allow the nosey Prime Minister to count more than a dozen scars. So far as I can find in the accounts I have read there is no way by which double counting can be separated from the total numbers reported. It is a fact that a soldier wounded in one encounter, returned to duty and wounded a second time in another battle is a casualty in each event but it is the same person injured within the army’s mobilised strength each time it happens. This means that whilst the deduction of the killed and missing from the total casualty figures provides a figure for the wounded, there is no means of separating the minor injuries from the dangerous and crippling ones or the effect of including soldiers receiving multiple wounds but able to return to duty on two or more occasions. Also it also worth remembering that many soldiers were wounded more than once, but returned to their homes and reestablished their lives when the hostilities ended in November 1918.

Note: As a statistic of the casualties suffered by the British Army to set another perspective on the issue; an analysis by the RAMC of the returns of injured treated revealed that 58% of the casualties treated suffered as a result of artillery fire, 39% as a consequence of rifle and machine gun bullets with the balance of 3% due to causes such as grenades, bayonet and gas. The problem again is that the perception of events is influenced by the concentration of circumstances in an entrenched front line, the infantry soldiers bore the brunt of small arms fire, artillery casualties occurred throughout the entire combat zone and sometimes further afield.

The procedure adopted for the British forces is therefore difficult or impossible to compare with German returns. The German system it seems did not include amongst the final reported total of casualties those soldiers “whose recovery was to be expected in a reasonable time”. The numbers quoted as ‘casualties’ for a battle or in total for the war, are not a like for like comparison.

The numbers for the French Army are even more questionable. At the commencement of hostilities in 1914 and for some time thereafter, wounded French soldiers had to be returned to the locality where enlistment took place; surely a system certain to lead to mistakes.

From the above brief comments if casualties are to be used as a measure of the performance on the battlefield of an army and its commanders the inconsistency of information is a serious problem. Another aspect of a comparison of casualties has to make reference to the numbers of mobilised soldiers and if there is to be strict accuracy only the members of units in the combat zone should be counted. The ‘non combs’ serving in their home country or base area away from the action should be discounted, such a sophisticated analysis is beyond my resources and generalisations will have to suffice. The conclusion reached is that for the purposes of this account the most reliable indicator for effectiveness of the armies concerned should confine itself to the numbers of combatants killed on the Western Front. It is a crude measure at best, but now the dust has settled the official figures as given below are one way to illustrate the human cost to the three major combatant nations of Western Europe and their armies.

Apparent from the foregoing once again must be that when looking at the subject of the Great War, 1914—1918, nothing is as it seems, and there are rich seams of controversy to be mined wherever one looks. That said, some crude comparisons are available and are quoted. A statistical section follows with even more confusing details.

| Country | Population in 1914 | No mobilised. | No killed. | % killed. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Britain | 45,750,000 | 8,900,000 | 750,00020 | 8.4 |

| France | 39,000,000 | 8,410,000 | 1,357,800 | 16.1 |

| Germany | 60,300,000 | 11,000,000 | 2,037,00021 | 18.5 |

The base information for this comparison is taken from Gordon Corrigan’s publication, Mud, Blood and Poppycock. In this book he quotes a figure for British killed of 702,410. This is close to the official return published in 1919, which as noted above is lower than the totals now commonly used by historians of note. The army fielded by Britain during the Great War had contingents from the Empire: Australia, Canada, New Zealand, South Africa and most notably India. To attempt to relate the casualties, killed or wounded, to the national populations of these countries is a task I cannot contemplate. In the tabular presentation I have used only the figures for Britain. If the numbers of those killed is expressed as a percentage of the total population of the countries the figures become, Britain 1.58%, France 3.7% and Germany 3.38%. I appreciate that these figures are playing with numbers; it is however a comparison of Allied and enemy losses which is, to say the least, startling.

Having advanced an argument above to explain the realities for numbers reported as wounded, figures available on the ‘Wikipedia’ website provide other interesting comparisons. The numbers cited for wounded are as follows: Britain, excluding imperial forces, 1,663,435; France 4,266,000, Russia 4,950,000, Germany 4,247,143. Taking into account the difference created because the German Army fought a war on two fronts, if 70% of the German casualties are allocated to the Western Front (see para below) that would give a figure for the number of wounded of 2,973,000, 44% more than the equivalent figure for British wounded! The number killed for the German Army on the Western Front would be 1,425,900, 90% more than British losses. The figures are at best rough estimates, they do reveal however a major discrepancy between the received wisdom of the ‘Butchers and Bunglers’ school of historical comment and the reality of my shaky estimates.

The implications of these figures have to be treated with caution, Britain fielded five infantry divisions and a cavalry division in August 1914, the French fifty-five and the German Army more than eighty divisions; more men in the field, more men get killed. The German assault on Verdun cost the French and German Armies dearly. In 1917 after the French spring offensive and the subsequent mutinies there was a period of hibernation by the French Army on the Western Front. Arras, Messines Ridge and Passchendaele were all British operations and bloody they were, compensating in some way for the small numbers who were available for commitment by Britain in 1914.

This is by no means all the story or anything like it, when considering the casualty statistics it is essential to bear the following in mind:

1. The number of men mobilised by Britain will include those who were deployed to other theatres of war such as Gallipoli, Egypt and Palestine, Mesopotamia (modern day Iraq), Serbia, Italy and East Africa. To set against these deployments, British forces in France included contingents from Australia, Canada including Newfoundland, India, New Zealand and South Africa.

2. The German Army was fighting on two fronts, Russia in the East in conjunction with the armies of Austria Hungary as well as the Western Front in Belgium and France. The best information I have found indicates that the German Armies’ maximum deployment of troops to the Eastern Front was 30%. The commitment to the Western Front would have been 70%. Adjusting this figure of the number mobilised to this ratio results in a deployment of approx 7.5 million in the German Armies confronting combined British and French manpower resources of 16,875,000. A ratio of 2.25:1 in favour of the Western Allies. Conventional military doctrine is that the ratio of attackers to defenders should be 3:1. That though does not allow for the Allies concentrating forces at the point of attack to achieve temporary numerical superiority.

3. Applying the same ratios to the German casualty figure the numbers killed in German Armies in France and Belgium during the fighting would be approximately 1,222,200 (15.3% of mobilised strength).

These crude adjustments of figures put another perspective on the arguments; French casualties would have been 11.4% more than the projected figure for the German Army, British casualties 18.5% less than the German figure. Another measure is to index the casualty totals, using the British figure as 100, the German casualties, based on the above estimated Western Front strengths and losses, would be 122 and for the French, 139.

Just as a reminder, the Germans were defending their gains in Belgium and France, the Western Allies were fighting to restore the ‘status quo ante’, for this to be achieved the biggest siege in history had to be broken.

Somewhere in the generalised myths of this war I seem to recall it is the British commanders, Haig in particular, who stand accused of careless commitment of troops to battle with a consequent excess of casualties. All is not as it seems, yet again.

A noticeable aspect of the texts of many of the accounts of the Great War is the liberal use of emotional or pejorative adjectives when the issue of battle actions, casualties and achievements are considered. A writer/commentator whose text relies on such words as; fiasco, needless, extravagant, prodigal, squander, fritter, slaughter and so on gives a clear indication of prejudice. The words are a clear warning to any reader to treat the opinions with caution. Any half way decent manager will admit that many decisions and plans made in business are based on information as appreciated at the time, with some allowance for the unforeseen, but success is never guaranteed. Many times a manager takes a chance, only when the effect on performance is seen in the accounts is the quality of their decisions revealed, managers though deal with accounts reckoned in cash, not human life.

Having expressed reservations about the value of unqualified casualty figures there are some published details which express the scale of the fighting by the armies on the Western Front and these are summarised below, not to point to failures, but to offer some information to enable the scale of the undertaking and the extent of the human endeavour consumed by the war of 1914—1918 to be remembered.

| Engagement. (year) | Total casualties. (all forces) | British. | French. | German. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neuve Chappel (1915) | 23,500 | 10,500 | n/c* | 13,000 |

| 2nd Ypres (1915) | 95,000 | 60,000 | n/c* | 35,000 |

| Champagne(1915) | 205,000 | n/c22 | 145,000 | 60,000 |

| Verdun(1916) | 720,000 | n/c22 | 380,200 | 339,800 |

| Somme(1916) | 1,070,000 | 450,500 | 200,000 | 419,500 |

| Chemin des Dames (1917 Spring offensive) | 160,000 | n/c22 | 120,000 | 40,000 |

| Passchendaele (1917 3rd Ypres) | 470,000 | 245,00023 | n/c22 | 200,000 |

| Spring Offensive (1918) | 270,000 | 150,000 | allied total | 120,000 |

| Final offensive | 350,000 |

If the daily casualty rates of some of the battles are considered the details again help to define the scale of the endeavours. For the Somme in 1916 which lasted 141 days the daily rate of British casualties was 3195, Arras in 1917 lasting thirty-nine days was 4076 per day, 3rd Ypres was 2323 per day and the advance to victory beginning in August 1918, lasting ninety-six days was 3645 per day.

These details all reinforce the opinion already expressed that with a subject so vast, almost any argument can be sustained by using well selected information favourable to your personal point of view. A situation which should serve as a caution to many is summed up in the well worn adage “I‘ve made up my mind please don’t confuse me with the facts”.

In a conclusion for this portion, attention has to be turned to two of the most persistent myths that sustain prejudice on the issue of the Great War, firstly, that the losses amounted to the death of a generation. A generation is generally regarded as twenty-five years and, allowing for an even spread of soldiers in the age group eighteen to forty-three years, almost one million British Army soldiers are buried as a result of enemy action, 2.18% of the total population, approx 6.5% of the relevant age group of the population in 1914, a grievous but not unsustainable loss. It is not a generation, however you reconstruct the arithmetic. Secondly, the more difficult issue raised by the losses to ‘Pals’ Battalions’ such as Accrington, Bradford and Leeds. Some writers put aside the folklore that surrounds the effect of the day in early July when numerous homes received the dreadful telegram that opened with the words ‘The War Office regrets to inform you that Private Thomas Atkins no 88465 is reported killed in action’ or one of the awful alternatives. To suggest as some do that the pain was equally spread through the nation and was therefore not special to one place is to misunderstand the communities of places such as Accrington, a northern mill town. More than 200 dead in one day, there would not be a family unaffected by the loss of a husband, son, brother, cousin, fiance or nephew. The extended families that formed the basis of the close communities of such towns were both the strength and the weakness of the ‘Pals’ Battalions’; the grief of these communities must have been overwhelming. Small wonder there is folklore. Do not believe all that is written on the subject, but do use your own observations and mark the lengthy list of the names on the war memorials of our towns and villages. Beware at all times the professional media personalities and grief mongers with their crocodile tears.

To return finally in this portion of the account to the extent of the casualties, killed and wounded, and avoiding adjectives it needs to be repeated that all of the casualties Ᾱ every single one of them Ᾱ was unnecessary, this was a war that should never have taken place and Kaiser Wilhelm II, his army staff and the German nation all must accept responsibility. That said, when reading Ernst Younger’s Storm of Steel there is no recognisable acknowledgement by him in the text that the occupation of another nation’s territory was in anyway wrong; quite remarkable.

The ‘Thankful Villages’

This term originated to describe the few communities, villages throughout the land, whose young men, needed for the armed forces of the Crown, were thankful; for all their men returned alive to their homes on completion of their service at the end of hostilities. Remarkable as such an event may seem.

The originator of this term was a writer and journalist, Arthur Mee, who wrote a series of guides to the counties of England and Wales titled King’s England published during the 1930s. He expressed the view that there were at most thirty-two such communities, although he could only be positive about twenty-four. Later research has identified forty-one parishes who have the distinction of a ‘Thankful Village’ from the 16,000 such communities there were reckoned to be, when hostilities ceased in 1918.

The distribution of the parishes is quite random, twenty-one of the counties of England and Wales have villages that qualify. Somerset for example has seven of the total, Lincolnshire and Nottinghamshire four each, Gloucestershire three, Lancashire and Northamptonshire two each. The remainder, thirteen counties, each had one of these fortunate communities. Notable amongst this last group was the village of Arkholme in Lancashire which saw fifty-nine of its men go to war and all returned to tell their stories, or like so many ‘keep their peace’. The experiences were so often shared only with those who had lived the experiences of the fighting man.

Casualty Statistics; Commentary

1. Source

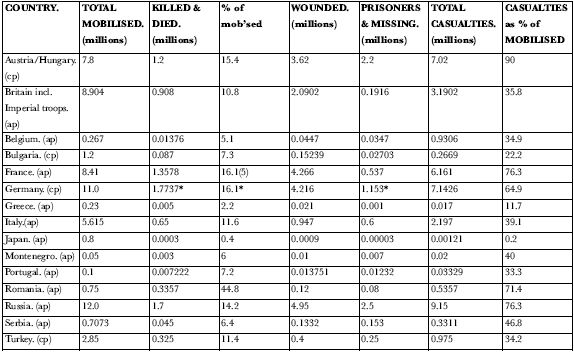

The compilers of the table of casualties qualify the information with the warning that the figures quoted are estimates compiled from reliable sources, all of which vary.

2. Commentary

2.1 The table of casualties is the most comprehensive summary found in the readily accessible sources of information, books and websites. The detailed figures vary, as is common, between sources and this issue is referred to in the main body of the text. The variation of detail between the individual sources does not upset the general pattern of losses sustained.

2.2 The figures from Table I demonstrate clearly that the war was essentially between seven combatant nations, Austria/Hungary, Britain, France, Germany, Russia, Italy and Turkey; the last two nations fighting in their own theatres of war and outside the Western Front battles.

2.3 The number of troops mobilised by nations is a reflection of several factors such as the population total, geography, national resources etc. The contribution of Japan was confined to the Pacific and maritime actions, Montenegro and Greece, the Balkans; America her late entry (April 1917) to the war and the long lead time needed to put the first battle equipped division into the field (ten months). British forces committed to the war included troops from the Empire. Any attempt to calculate the proportion of the male population of the Empire has to reconcile the huge population numbers of India such a factor will distort the credibility of the argument.

2.4 The term casualty/casualties has been discussed in the main text, the figures contained within the table illustrate well the anomalies that have arisen through the various practices adopted by different armies and one suspects in some cases the appalling standard of administration. For example; Austria/Hungary is reported as having 2.2 million ‘prisoners and missing’, 28% of the mobilised force; Russia 2.0 million, 20%; Germany 0.89 million, 8.09%; France 0.537 million 6.4%; Britain 0.1916 million, 2.15%. In the case of both Austria/Hungary and Russia there must be the suspicion that the numbers killed is seriously under reported.

3. Statistical Information

“There are,” said the sage; “Lies, damned lies and statistics”*. Venture here at your peril! (* attributed variously to Mark Twain, Henry Labouchere, Abraham Hewitt and Cdr. Holloway R. Frost)

3.1. Percentage calculations, carried out in the time honoured way we all experienced during our education. Beware though, percentages are stand alone figures, the ‘averaging’ of a series of percentages is a big statistical no no. And yes I did come across one author who tried to argue a point based on such a trick.

3.2. Average (preferred statistical term is mean), the measure of central tendency. We are all used to the common expressions; average temperature, speed, weight, etc. The arithmetical mean which is the one in use here is calculated in the conventional way. This is a straightforward arrangement and calculation, not difficult to undertake with modern electronic aids. The weakness is that the outcome of the calculations can be distorted if the figures used are heavily ‘skewed’ that is if there are too many results at one of the extremes of the range. This weights the average and can distort conclusions, unless the user has his wits about him or her. Also as with percentages, averaging averages is not an option unless provision is made for the different population sizes.

There is a second version of the ‘mean’ which in the context of the type of information contained within the casualty table has much to commend it; the median. This is a value of central tendency specifically related to the range of values to which it refers. It is calculated as the midpoint figure between the highest and lowest in the series without reference to the actual value of results in the range. Also unlike the mean referred to above, because the values remain unchanged the median for a range of percentages is a valid statistical comparison between the median of other relevant data.

When the mean and the median are used in conjunction with each other a clearer idea can result of the meaning of the figures. That is why politicians don’t use them together.

4. Statistical Review

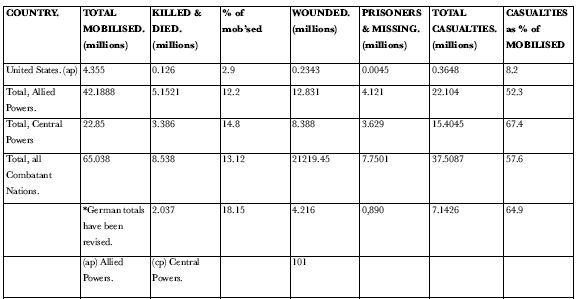

4.1 The tabulations that follow compare the casualties of the seven major combatant using the criteria of numbers mobilised. Four of the nations fought exclusively in their own theatres of war. In the East, Russia and Austria/Hungary, Asia Minor and the Middle East, Turkey and Southern Europe, Italy. The armies of these countries mobilised 87% of the combatants engaged in the Great War. The United States has been excluded, though it mobilised 4.35million men (6.7% of mobilised forces) the number deployed and the limited time during which they were committed to the conflict was thought to be insufficient for inclusion of their data, in this comparison.

The three tables that follow overleaf compare the effect of casualties for national armies with the median for this group of combatant forces.

Table II; Numbers killed and died as % of numbers mobilised

| NATION | KILLED as % of MOBILISED |

|---|---|

| Britain | 10.8 |

| Turkey | 11.4 |

| Italy | 11.6 |

| Median | 13.45 |

| Russia | 14.2 |

| Austria/Hungary | 15.4 |

| France | 16.1 |

| Germany | 16.1 later revised to 18.5 |

Table III; Number of casualties as % of numbers mobilised

| NATION | CASUALTIES as % of MOBILISED |

|---|---|

| Turkey | 34.2 |

| Britain | 35.8 |

| Italy | 39.1 |

| Median | 62.1 |

| Germany | 64.9 |

| France | 76.3 |

| Russia | 76.3 |

| Austria/Hungary | 90.0 |

Table IV; Total of Casualties

| NATION | NUMBER of CASUALTIES(millions) |

|---|---|

| Turkey | 0.975 |

| Italy | 2.2 |

| Britain | 3.19 |

| Median | 5.06 |

| France | 6.16 |

| Austria/Hungary | 7.02 |

| Germany | 7.14 |

| Russia | 9.15 |

NB. The casualties incurred by the German Army is a total, the proportion of those which resulted from action with the Austro/Hungarian Armies on the Eastern (Russian) Front is not shown in the sources consulted. Taking the division of resources as 70/30, Western to Eastern, the figure for % killed as a proportion of those mobilised of 18.5% has some credence. It seems unlikely that Germany would have committed less than 70% of its effort to its principal theatre of operations.

5. Death of a Generation?

The intention of this section is to use a model to look at the implications of the numbers killed for the society when hostilities ended and the actuality of war was removed from the social, political and economic equation of the day. Populations had been severely depleted by the death of significant numbers of men, concentrated as these losses were in a generational age span of twenty-five to thirty years: was it though the ‘death of a generation’?

This change needed serious social and economic adjustments affecting, as it did, mainly the age group eighteen to forty-five years or thereabouts and there would be a disproportionate number in the affected cohort below the age of thirty-five years. Why? Because high intensity conflict is for young and fit men. Older soldiers have their place as leaders and trainers, but as front line footsloggers their contribution diminishes as age increases, the task is too physically demanding. Capt. J. C. Dunn, RAMC, Medical Officer, 2nd Bn, The Royal Welch Fusiliers makes the point a second time in his diaries published as, The War the Infantry Knew, Chap II and he should know!

The dead of the combatant armies we have to assume would have been of the same age group. This is not to say that older soldiers were not killed, artillery has a long reach. Also as the war lengthened all the combatant nations were forced to find soldiers from age groups which in 1914 would not have been considered.

The model has been constructed using various assumptions which are set out below. It is an attempt, no more, to provide an analysis by comparison of between three of the combatant nations of the effect of depleting national populations in the ‘breeding’ cohort of the social structure.

The assumptions made in the preparation of the model were as follows:

• National populations are divided equally male and female; there is in reality a slight imbalance with more females than males both by numbers and longevity.

• A generation span has been assumed to be twenty-five to thirty years. Casualties were concentrated in the age range eighteen to forty-five years, but a notional 5% adjustment has been introduced for those outside this age range.

• The national population assuming no distortion was divided into cohorts by age. The cohorts would reduce numerically by reason of natural causes over the years. The largest group would be the youngest and with equal age ranges each cohort would be smaller than its predecessor by reason of: the increase in national birth rates, illness, accident and emigration.

• The rate at which the cohorts diminish and the size of each, are assumptions for the purposes of this model.

Taking the information and the breakdown into age cohorts, the effects of the losses can be looked at in detail. The three combatant nations considered in alphabetical order are; Britain, France and Germany.

Britain

Population, 45,750,000. Males, 22,875,000. No. mobilised, 8,500,000. No. killed 775,000

Population cohorts by age range, percentage and number (millions).

| Age | 0–5 | 6–15 | 16–25 | 26–35 | 36–45 | 46–55 | 56–65 | 66–75 | 76+ |

| % | 6 | 16 | 15.5 | 14.5 | 13 | 12 | 10 | 8 | 5 |

| No. | 1.373 | 3.66 | 3.546 | 3.317 | 2.974 | 2.745 | 2.288 | 1.83 | 1.144 |

Crucial population age group, ages sixteen to forty-five: 9,837. 43% of male population.

No. killed, adjusted to 95% for out of age range casualties, 0.735, ie 7.5% of crucial age range.

France

Population, 39,000,000. Males, 19,500,000. No mobilised 8,410,000.

No. killed 1,391,000

Population cohorts by age range, percentage and number (millions).

| Age | 0–5 | 6–15 | 16–25 | 26–35 | 36–45 | 46–55 | 56–65 | 66–75 | 76+ |

| % | 6 | 16 | 15.5 | 14.5 | 13 | 12 | 10 | 8 | 5 |

| No. | 1.17 | 3.120 | 3.023 | 2.878 | 2.535 | 2.340 | 1.950 | 1.560 | 0.975 |

Crucial population age group, ages sixteen to forty-five: 8,436. 43% of male population.

No. killed, adjusted to 95% for out of age range casualties, 1.391, ie 16.5% of crucial age range.

Germany

Population, 60,300,000. Males, 30,150,000. No mobilised, 13,250,000.

No. killed, 2,037,000

Population cohorts by age range, percentage and number (millions).

| Age | 0–5 | 6–15 | 16–25 | 26–35 | 36–45 | 46–55 | 56–65 | 66–75 | 76+ |

| % | 6 | 16 | 15.5 | 14.5 | 13 | 12 | 10 | 8 | 5 |

| No. | 1.809 | 4.824 | 4.673 | 4.372 | 3.920 | 3.618 | 3.015 | 2.412 | 1.508 |

Crucial population age group, ages sixteen to forty-five: 2.965. 43% of male population.

No. killed, adjusted to 95% for out of age range casualties, 2.037, ie 14.9% of crucial age range.

The question therefore is did the losses amount to the death of a generation? The answer has to be a qualified no. There were towns and communities that suffered disproportionate losses and to which attention was naturally drawn. The British nation lost 7.5% of its young men a significant but not devastating proportion, had it been evenly spread which it was not. It followed from this that in an age when the social morality of the day frowned on extra marital activities a young married man would not ‘play away’ and have children outside a regular family. In such circumstances, things being as they were, young women went unmarried and essentially childless. One estimate puts the figure at one million; that though seems likely to be an overstatement. They were not though lost to the nation and the years between the wars saw women taking employment and gaining seniority and respect for their contribution, often against strong male opposition in professions such as medicine, teaching, journalism and politics.

German losses of this crucial generation were double those of Britain; France suffered losses to an even greater extent. The British legend, as is all good folklore before it, is founded in fact, but accuracy is lost in translation.

6. Summary

6.1 The data included in the tables should be interpreted, as should all statistics, as confirmation of general circumstances and perspective, trends rather than proof positive of any exact number or specific proposition. The issues of significance that can be summarised from the information are as follows.

6.1.1 The figures of ‘Prisoners and Missing’ in the returns of Austria/Hungary and Russia are of such magnitude when compared to the numbers of ‘killed’ and ‘wounded’ that serious doubt arises as to whether the numbers for any of the categories are an adequate reflection of the extent of the damage done to the armies and nations involved in the conflict.

6.1.2 The number of ‘Prisoners and Missing’ reported for the German Army is also too great for such a well disciplined fighting organisation. This may account in part for the upward revision of numbers killed for the German Army from the figure quoted above of 1.7737 million (16.1% of mobilised strength) to a more recent higher total of 2.037 million (18.5% of mobilised strength). This increased figure for Germans killed should lead to a reduction of the ‘Prisoners and Missing’ figure from the original 1.153 million to 890,000 which remains an astonishingly high figure for the thorough Teutonic state of Germany.

6.1.3 The arrangement of the figures for the seven major combatant nations in rank order with the ‘median’ for comparison is as near as we are likely to come to identifying the true position of armies in the casualty league. The armies under British command suffered less by way of numbers killed, wounded, prisoners and missing than any of the other combatant armies on the Western Front and in terms of the war fought in Europe, Asia Minor and the Middle East did not sustain disproportionate casualties in pursuit of victory.

6.1.4 As casualties have a causal connection with the quality of command the evidence of these statistics supports a conclusion that although not perfect, the achievements of British generals was at least as good as that of other combatants and better than those whose national armies casualties exceed the median for the category; France, Germany, Russia and Austria/Hungary. Despite the losses the British Army made a better job of conserving its manpower than the other major combatant nations.

QUOD ERAT DEMONSTRANDUM.

Dedication.

Miss Edna Snell24.

(an unremarked casualty of the conflict)

This section is dedicated to Miss Snell who died aged 105 in the millennium year 2000. At the age of twenty years in 1915 her fiancée, Billie Smith, a Kitchener soldier aged twenty-two years, was killed in France. She never forgot her young love and died in her sleep holding her only remaining memento, a photograph on the back of which he had inscribed his last message of affection.