Chapter Thirteen

Norah

We are worried about Christabel

New York Times 6 April 1912

IN MAY 1911, just after Sylvia had returned from her first trip to America, the death of a man she didn’t know, in his stately home in a faraway village she had never visited, was to open the way to a remarkable friendship and so to the next stage of her life.

Hugh Lyle Smyth – very distantly related to composer Ethel Smyth – was chairman of the Liverpool-based family firm of Ross T. Smyth, the world’s third largest grain merchants. He died, leaving his fortune to be shared between eleven children. Seventh in line was his daughter Norah, who received about £20,000. It was Norah’s generosity with this legacy that was eventually to give Sylvia the opportunity to form her own breakaway movement.

Born in 1874, Norah had grown up in the family home, Barrowmore Hall, in the Cheshire village of Great Barrow. Specially commissioned by her father, the turreted mansion was embellished by terracotta heads of the entire Lyle Smyth family. The 220-acre gardens were among the finest in Cheshire and included a large mill pond with gates that could be opened to flood the meadows for skating in winter. A dutiful army of servants cared for the household and the collection of antiques and Constable paintings. It was all a long, long way from Sylvia’s chosen world of the deprived and underprivileged.

Norah Smyth, like Sylvia, was a woman whose heart was with the downtrodden poor. She was 38 years old when her father died; he had prevented her from marrying a cousin and had not allowed any of his daughters a university education. Norah grew up a rather studious and artistic woman, finding an outlet for her considerable intelligence in village activities. She was deeply involved with the local church (she played the organ) and was regarded as rather eccentric, largely due to a taste for ties and her fondness for a pet monkey called Gnome.

Norah and her sister, Georgina, developed an interest in the Suffragette Movement and became active locally. In 1906, they went together to the Trafalgar Square Rally, where for the first time they saw the Pankhursts. But it was probably not until her father’s death that Norah finally left home and travelled to London to live, where, dressed ‘as much like a man as possible’, she became a chauffeur to Emmeline.

In May 1911, the Conciliation ‘carrot’ was once again debated in the House and deferred, on the promise to devote a week to a Bill to be debated later in the life of that parliament. Christabel and Emmeline accepted this assurance with optimism and set about organising a massive seven-mile parade to take place on the Saturday before the coronation of King George V and Queen Mary.

On 17 June 1911, militants and non-militants joined together for the first time to celebrate. Sylvia describes it as ‘a triumph of organisation, a pageant of science, art, nursing, education, poverty, factory-dom, slumdom, youth, age, labour, motherhood, a beautiful and imposing spectacle’. Mrs Wolstenholme-Elmy, at the age of 78 now ‘the oldest Suffragette’, stood watching from a balcony in St James’s Street, where she took the salute as almost 1,000 former prisoners, including Sylvia, passed by.

The summer and autumn of 1911 were creative and, on the whole, happy times for Sylvia. She was comparatively unaffected by the trouble fermenting beneath the surface at the Clements Inn headquarters, although she was continually concerned about unrest in Britain and mainland Europe. Hardie had been busy distributing a book by Norman Angell of the Daily Mail entitled The Great Illusion. It had been published originally in 1908 but echoed the views that Hardie himself had been propagating for years: ‘You might sink the German fleets, you might even by a miracle destroy the German army but the invasion of the German trader will continue.’ At home, strikes spread and Hardie declared sadly, ‘the machinery of national life is slowly stopping’.

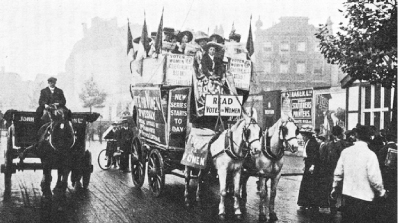

The Suffragettes protested in large numbers, some on vehicles with banners calling for Votes for Women.

On the lighter side, Sylvia had developed an unexpected interest in country dancing, to which she had been introduced by Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence’s friend, Cecil Sharp. She started work on some studies of girl Morris dancers in preparation for a large picture but never finished it. One of Sylvia’s East End helpers was Ada Walshe, who recalled one of the displays with affection, ‘Some of the dances were religious in style, some pagan, prayers to the sun etc. …. the floor of the platform had not been washed and the dancers’ feet became black. The audience roared with laughter and behaved very badly and for once I saw Sylvia almost crying with laughter and trying to hide it.’ Irrepressible mirth did not come easily to Sylvia.

She was also working closely with Hardie on amendments to the National Insurance Bill, which would increase the proposed benefits. The WSPU had been opposed to the Bill, just as they were opposed to all government measures in which women had not been involved, but Sylvia judged that this was unnecessarily destructive to an important, far-reaching piece of legislation. On one occasion she tackled the elderly anti-suffragist Lord Balfour, appealing to him to take up her amendments in the interest of the lowest paid workers, who were mainly women. He agreed and she admitted modestly later, ‘I felt like a pigmy walking beside this huge figure.’

As the year drew to a close, Sylvia was asked by Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence to organise a week-long fund-raising exhibition and Christmas Fair in the Portman Rooms. She was thrilled and gratified to discover that most of her plaster casts, drawings and models made for the skating rink event were reusable, and together with some new arches, they looked ‘as solid and permanent as stone’.

Some time before, Keir Hardie had given Sylvia a beautiful Eighteenth Century book of costumes illustrated by the renowned artist Pine. ‘I hope indeed he picked it up at less than its value,’ she comments in The Suffragette Movement. ‘It was stolen from me some years later.’ Sylvia used an illustration of a village fair in the book as inspiration for the stall holders’ late Eighteenth Century costumes: gentlewomen, fisherwomen, market women, weavers, workers of all sorts, a gipsy fortune-teller with her two green birds, a roast chestnut seller, a town crier, a ‘zanny’ with his odd fool’s cap. There were coconut shies, old London cries and much music arranged by Ethel Smyth. Sylvia, however, was so exhausted by her efforts that she went home, fell asleep on the floor and missed the fun of witnessing Keir Hardie riding on the hand-propelled roundabout made specially for her by local carpenters; 7,000 people visited the fair.

But behind the jollity, WSPU members were also now in training for their proposed stone-throwing onslaught. They would drive out at dusk down country lanes looking for flints, which were later put into black bags ready for the attacks. Sylvia found an excuse not to go with the women, explaining that she was so committed to the Fair she did not want to risk arrest, but her conscience was clearly troubling her. A few days after the Fair, Emily Wilding Davison, first class graduate, governess and teacher, who was too much of a rebel even to be employed by the WSPU, carried out the first arson attack. On her own initiative, not Christabel’s, she set fire to a letter box.

By the time Sylvia returned from America after her second tour early in 1912, she had become even more alarmed by the mood of the movement being directed by her mother and sister. On Friday, 1 March 1912, while Sylvia was still on her second trip to America, well-dressed women suddenly produced hammers from their handbags throughout central London. They smashed the windows of Marshall and Snelgrove, Fullers teashops, Lyons Corner Houses and moments later attacked Swan and Edgar, Liberty and many government offices. The Daily Telegraph reported that many of the finest shop fronts in the world had been destroyed. The following day, 200 women, including Mrs Pankhurst, were arrested in Downing Street. They all refused bail and were remanded in custody.

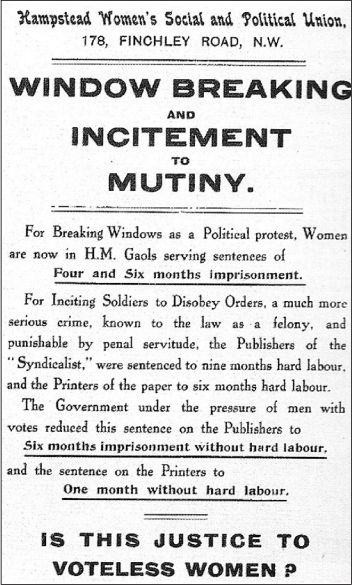

A call for action on a Suffragette’s handbill.

On Tuesday 5 March, there was a police raid on the WSPU headquarters. Documents and papers were seized and the Pethick-Lawrences were arrested and charged with ‘conspiracy to incite certain persons to commit malicious damage to property’. A huge haul of papers was removed for investigation. Mrs Pankhurst was included in the charge, although she was already in prison.

Christabel was nowhere to be seen. In fact, she was in her new flat in another part of London, but on being warned of the drama in Clements Inn, she decided, ‘in a flash of light’, that her own imprisonment would leave the movement temporarily leaderless and that she should avoid arrest at all costs. She escaped to Nurse Pine’s refuge, disguised as a nurse. She then took a taxi, unobserved, and stayed overnight with a friend. Then, disguised yet again, this time in a black cloche hat and a long black coat, she was driven to Victoria Station. There she caught the train to France, where she became ‘Amy Richards’. The Drama Queen had given her most theatrical performance. She would continue playing the lead from the revolutionary stage of Paris. As a public relations operation, it was brilliant. The newspapers loved it.

Even in America, the press was on her trail. The New York Times on 5 April 1912 alleged, ‘Miss Pankhurst is in hiding here. She arrived on the Cunard liner, Mauretania, 30 March.’ They claimed Christabel was under an assumed name and had met Sylvia, who gave her some money from the proceeds of her tour before sailing for England. Nowhere has this story been supported and certainly neither Sylvia nor Christabel mention such a transatlantic tryst. However, in 1972, Nellie Rathbone, Sylvia’s secretary from 1913 to 1920, told author Brian Harrison that the story was true.

On 6 April the New York Times editorial said: ‘The transformation of Miss Christabel Pankhurst, one of the most ubiquitous, aggressive, demonstrative personages of her time, always in sight and hearing, into an elusive, silent invisible state has become an international mystery. We are worried about Christabel.’ Even the devoted Annie Kenney did not know where Christabel was until she received a mysterious summons to Paris, putting her in ‘supreme charge’ of the movement, hurtfully over Sylvia’s head, while Emmeline and the Pethick-Lawrences were in prison.

For the next few months, Annie Kenney made weekend trips to Paris to receive her orders. ‘The very thought of the journeys to Christabel made me feel seasick,’ she wrote in her autobiography. ‘Before I left my head would be so full that I had to beg Christabel to give me no more instructions for another week.’ But by the time she returned to London, there would be a long letter waiting for her, full of the things they had forgotten to discuss. ‘Christabel’s vitality was good for me … she revitalised all she came into touch with. The Saturdays in France were a joy. We would walk along the river or go into the Bois or visit the gardens. Whoever saw us would also see stacks of newspapers, pockets stuffed with pencils and always a knife to sharpen them.’

At home, industry was in uproar and strikes were threatened. King George V had written in his diary on 2 March, ‘I talked to him [the Postmaster General] about the coal strike and suffragettes who smashed a lot of windows again in the West End last night.’ On 4 March he added, ‘It has been an awful day with a lot of rain. The Suffragettes broke a lot more windows today of the ministers and shopkeepers in Kensington and about 100 more arrested outside Westminster tonight. Bed at 11.30.’63

On 18 March, one million miners came out on strike, affecting all industry and bringing misery to families throughout the country, a situation that was barely recognised by the WSPU leadership, who were too occupied with their own affairs. Civil war seemed imminent in Ireland and Keir Hardie and others were continually warning about the future.

Christabel was becoming restless. The Suffragette struggle was being eclipsed and new policies were needed to keep the Movement in the headlines. On the whole, the mood in the provinces was strongly against militancy and certainly against vandalism, a view shared increasingly by Adela working in the north of England.

On her return from America, resolute with good intent and disguised by Nurse Pine, Sylvia crossed the channel to see her sister, anxiously peering in all directions to be sure she was not followed. She changed her clothes in railway stations to avoid recognition and arrived, unexpectedly, at Christabel’s Paris apartment. Christabel was eager to rush the reluctant Sylvia around the city sightseeing, shopping for clothes she did not want, indeed, anything to avoid the subject she had come to discuss. It was a devastating experience:

I asked her what I might do to help. ‘Behave as though you were not in the country,’ she answered cheerfully. ‘When those who are doing the work are arrested you may be needed and can be called on.’

To me the answer was ludicrous; with our mother facing a conspiracy charge and the movement limitless in its need. ‘You don’t expect me to behave as though I were afraid?’ I asked her. She conceded amiably. ‘Well, just speak at a few meetings.’ Instinctively, she thrust aside anyone who might differ from her tactics by a hair’s breadth. ‘I would not care if you were multiplied by a hundred, but one of Adela is too many,’ she had said to me.

Now it was clearly evident to me that I might become superfluous in her eyes. I made no comment … I had always been scrupulous neither to criticise or oppose her … I was still prepared for the sake of unity to subordinate my views in many matters to hers, but her refusal to ask any service of me would leave me the more free to do what I thought necessary in my own way … I could not express my views on policy to her, she desired only to impose her own. That, too, I accepted as one accepts the rose bears the thorns … I left by the night boat unable to endure another day.

In her autobiography, Christabel does not even mention her sister’s visit.

Sylvia returned from Paris to find Keir Hardie in high spirits. The mood was short-lived, for they were both aware of an ominous switch in attitude towards the WSPU. Unlike Christabel, Sylvia foresaw the campaign in the wider international context of events in Europe, and social and political unrest at home. She could also see that the new policy could rebound and result in draconian retaliatory measures by Parliament.

On 15 April 1912, the first edition of the Daily Herald was launched by George Lansbury, with Annie Kenney’s brother, Rowland, as editor. The Herald put a page at the disposal of the Suffragettes and Lady De La Warr gave a generous donation. The very first edition carried the terrible story of the sinking of the Titanic. The news personally shocked Sylvia Pankhurst, Keir Hardie and George Lansbury, for their champion, W.T. Stead, was amongst those who had drowned. He had apparently, and heroically, held back to let others into the lifeboats before him and was last seen standing at prayer on the deck. For many years Stead had been a constant campaigner for improved welfare in the East End.

Public hostility towards the Suffragettes was becoming more aggressive and women were frequently physically attacked. Sylvia was not alone in her anxieties: the Pethick-Lawrences, naturally peaceful people, were uneasy about vandalism too. However, Sylvia was still determined to keep the movement alive for her mother and especially, at that moment, to secure better conditions for all her friends and colleagues in prison.

The six-day conspiracy trial began at the Old Bailey on 15 May. Serious as the matter certainly was, Sylvia’s description of the scene has a tragi-comic flavour which belies the familiar idea that she was without humour:

That court of mockery and doom … a grim burlesque … a caricature of the Middle Ages … among the wigged functionaries of the legal sphere, wherein no woman might yet intrude, sat Sir Rufus Isaacs, the Attorney General, with his handsome Jewish face and dark hawk’s eye. Beside him ‘Bodkin’, ‘Sir Archibald’ as he presently became … ruddy and bald with an egg-shaped head, he was the very image of Alley-Sloper, depicted in the comic papers the servants were reading in the kitchen when I was a little girl in Russell Square … In the dock two women, each with her special charm, serenely determined to make a platform of it: the one impervious to small points, searching to fathom the inner mysticism and eternal verities of the situation in which they found themselves; the other swifter and more impassioned than a tigress … She was now in the flood tide of the last great energies of her personality before the disintegrating ravages of old age should begin to steal upon her.

The three defendants were found guilty and sentenced to nine months in prison but not in the first division. Frederick Pethick-Lawrence was forced into bankruptcy and expelled from the Reform Club. A major hunger strike was immediately threatened unless the prisoners’ status was upgraded. The request was refused. There was uproar, and Prime Minister Asquith was not only overwhelmed with protests from 100 MPs, but in addition, representatives from the church, universities and suffrage organisations from all over the world bombarded him. Among those working with Sylvia to help the prisoners was an old family friend, the genial Liberal Josiah Wedgwood, who appreciated her genuine concern for her mother’s health and provided her with a shoulder to cry on.

Even then there were light moments in a dark story. On one occasion, the conductor Thomas Beecham64 recalled a visit to Holloway, where he saw ‘the noble company of martyrs marching round and singing lustily their war-chant while the composer, beaming … from an over-looking upper window, beat time in almost Bacchic frenzy with a toothbrush’. On another occasion, the prison commissioners reported that Dame Ethel Smyth had visited Holloway with some wine which, she claimed, Emmeline needed for her health. The Home Office wrote solemnly, ‘Is Mrs Pankhurst being given wine and, if so, is any particular brand necessary?’ to which the Governor replied, ‘14 bottles of Chateau Lafitte have been delivered and locked up in the chief warder’s room.’

That same day, 25 May, Sylvia was in Merthyr where she spoke with new poise and power at an ILP Conference and where Hardie referred, to her acute embarrassment, to the status of ‘the lover’. In the future, he said, not only would the bonds of poverty be broken, but also the shackles of convention. This could not be achieved until women stood free and equal side by side, ‘with their husbands, brothers, lovers, friends’.

The hunger strikes and the force-feeding continued, although Emmeline Pankhurst, perhaps because of her age (she was now 54), was not subjected to this torture. Emily Wilding Davison made three unsuccessful attempts to throw herself from the prison stairway onto some wire netting, 30ft below. On the third occasion she was knocked unconscious as she tried to hurl herself back from the net onto the stairway. She was returned to her cell and left alone. Despite her injuries, she was force-fed again next day. That event brought uproar to Parliament on 23 June in the person of the ever-emotional member for Bow and Bromley, George Lansbury. The Daily Telegraph described the scene where he accused the Prime Minister of torturing women and was ordered from the House amid chaotic scenes:

To the amazement of the whole House – an amazement so profound that the tumult immediately quietened down … Mr Lansbury began to stride down the floor in order to get nearer the Prime Minister … the member for Bow and Bromley shook his fist at him, pouring out half the time a torrent of incoherent abuse … he shouted that he ought to be hurled out of public life …

Mr Lansbury’s language was quite the least of his offences … it was his conduct and bearing that was the blind outrage. For there he stood, or rather crouched, shaking with passion … wholly carried away by blind rage … as though he were drunk with fury…

The Telegraph concluded tartly, ‘there are limits to the excesses of an overflowing heart’.

The public did not agree. Lansbury became a hero overnight – the congratulatory telegrams and letters which poured in occupy 427 pages of the Lansbury Collection. Later in the year, in November, Lansbury resigned and stood for re-election on the single issue of the women’s vote, a step Sylvia regarded as precipitate. She strongly disagreed with his decision that the Labour Party should vote against the government on all issues, including Home Rule, until there was universal franchise. She felt that this policy would involve losing many reforms that would be of benefit to the working classes.

One of the most persistent speakers against the WSPU in Parliament was cabinet minister Lewis Harcourt, MP. His beautiful Eighteenth Century mansion stood in gardens, designed by ‘Capability’ Brown, which ran down to the Thames at Nuneham Courtney, near Oxford. There, in the early hours of 13 July 1912, two women were involved in another WSPU escapade. They had travelled in a hired canoe and PC Godden found them standing near a wall of the mansion with hammers, inflammable material and matches. Helen Craggs, Harry Pankhurst’s would-be sweetheart, was arrested, but the other woman, chased by police dogs, escaped and vanished into the night. Who was the mysterious ‘other woman’? Sylvia knew her name, yet she has rarely been fully identified in any of the Suffragette histories. The police thought she was Ethel Smyth because the canoe was hired in the name of ‘Smith’, and Ethel was now a known Suffragette. But no. Ethel published her own characteristically forceful rebuttal of any such idea.

In fact, the would-be arsonist was Norah Smyth, who in the early 1960s, not long before she died, told the true story for the first time to her nephew, former diplomat Kenneth Isolani, when he went to visit her in Ireland. Knowing of his aunt’s love of paintings and antiques, he was puzzled that she could have been persuaded, even by Christabel, to destroy the Nuneham Courtney collection. ‘The East wing of the house was empty and uninhabited,’ she explained. ‘I escaped over the fields and took the boat back to Abingdon from where I travelled to Reading. In Reading I changed my clothes in a public toilet before crossing the Channel to Europe where I hid ‘til the dust settled.’

It was when she returned to London that Norah and Sylvia joined forces in Linden Gardens. Their friendship grew, based on shared socialist principles, fired by Sylvia’s reforming energy, guided by Norah’s practical common sense and nourished by her generosity. It was at about this time, too, that Zelie Emerson appears in the story. The dark-eyed daughter of an American industrialist from Michigan, she had developed an intense affection for Sylvia and was eager to play her part in whatever her heroine was doing.

Despite Christabel’s request that she should lie low, Sylvia was busier than ever that summer. Her American trip had given her enormous strength and, well aware of her new, if self-imposed responsibilities she undertook a gruelling round of massive meetings in every principal open space and park around London. Diplomatically, she made sure that Mrs Drummond was in charge of and credited for what was arranged, but it was actually Sylvia, with the lively, mercurial mother of seven, Lady Sybil Smith, who provided the ideas and the impetus.

It all came to a glorious conclusion with a WSPU Hyde Park spectacular on Bastille Day, 14 July, the day Emmeline Pankhurst celebrated her birthday. The women were joined by many of the suffragists, the Fabians and the ILP but not Millicent Fawcett’s NUWSS. They thronged the Park in their thousands in a glorious display of banners, bonnets and bands. Keir Hardie spoke from a cart, wearing a white suit and a red plaid tie.

However controversial their actions, there is no doubt that the WSPU talent for theatrical splendour had never been surpassed, and much of this was due to the artistic drive of Sylvia herself. She supervised the making of 252 scarlet caps and banners and hundreds of smaller flags, in a little garden studio in Kensington. She calmed her volunteers when the fabrics ran out, scoured London for white fringe and found it in John Barker’s hire department, left over from Queen Victoria’s funeral. By the light of candles in bottles, the girls worked on through the summer nights, feeding Sylvia cups of tea while she drew dozens of scarlet dragons on banners.

In the morning her legs were swollen to an enormous size but she was determined to speak as planned. And then, in the middle of it all, Sylvia received a telegram from Christabel in Paris. It asked her to burn down Nottingham Castle. ‘The request came as a shock to me,’ she wrote. ‘The idea of doing a stealthy deed of destruction was repugnant to me’.

_________

63.Royal Archives, Windsor, Diary of King George V.

64.Thomas Beecham (1879–1961) was the Artistic Director of the Royal Opera House and founder of the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra.