Chapter Sixteen

War on All Fronts

I tell you quite frankly that I have listened with the greatest interest to … a very moderate and well-reasoned presentation of your case and I will give it … very careful and mature consideration … on one point, I am glad to say I am in complete agreement with you … if you are going to give the franchise to women, you must give it to them on the same terms that you do to men … It is no good tinkering with a thing of this kind … If the change has to come we must face it boldly and make it thoroughgoing and democratic in its basis

Asquith’s reply to Sylvia following the

ELFS deputation on 12 June 1914

CHRISTABEL makes no mention of the final parting of the Pankhurst ways in her autobiography, no reference at all to what must have been the two most poignant and painful of family meetings in Paris, early in January 1914.

Sylvia was in Holloway between 4 and 10 January and, shortly after release, decided she had to respond to the summonses she had been receiving from her sister. She was reluctant to leave the country for fear of arrest and because she had so many commitments now in the East End. Besides, as she said, ‘I realised that, like so many others, I was to be given the “conge”.’74 But a truculent Christabel was not to be ignored and so, travelling with Norah for support and to represent the members, Sylvia left from Harwich in a private cabin, still feeling miserably ill after her prison experiences. They found that Emmeline too, was far from well, and it appears that Christabel, Pomeranian on lap, did all the talking. Norah, who was a loyal supporter of the WSPU but had nevertheless chosen to move with Sylvia into the East End, remained silent. ‘Like me, she desired to avoid a breach. Dogged in her fidelities and by temperament, unable to express herself under emotion …’

There seemed no end to Sylvia’s misdemeanours according to Christabel: she had spoken at Lansbury’s pro-Larkin meeting, contrary to WSPU policy; she worked with Lansbury – the WSPU ‘did not want to be mixed up with him’; she had a democratic constitution – the WSPU did not agree with that; the working women’s movement was of no value; Sylvia’s friendship with Lansbury and Henry Harben was unwelcome; the East London Federation was diverting funds that might be given to the WSPU (it is true that Harben was supporting both); Sylvia had her own ideas and they were not needed. ‘We want all our women to take their instructions and walk in step like an army,’ Christabel declared.

‘Oppressed by a sense of tragedy, grieved by her ruthlessness,’ Sylvia made no reply. They drove in the Bois de Boulogne, Christabel with her dog on her arm, but Sylvia was in no mood to benefit from the pleasures of Paris; she was suffering from fatigue and headaches, and she could see that her mother was pale and emaciated. In the afternoon, the conversation turned bitter and aggressive. Norah Smyth knew that donations due to the East London Federation had already found their way to Lincoln’s Inn. She challenged Christabel, who questioned the need of such a ‘simple’ organisation as theirs for money. Emmeline, now clearly distressed, tried to ameliorate the situation by offering some supporting funds to Sylvia, an idea firmly rejected by Christabel. ‘Oh no,’ she said, ‘we can’t have that. We must have a clean break.’

And so it was that the East London Federation was expelled from the WSPU.

Sylvia was in a daze, barely hearing Christabel’s words. Images of their childhood, the early days at Green Hayes and in Russell Square, were rushing through her mind as the words of their father echoed around the room: ‘You are the four pillars of my house’. Emmeline must have recalled those words with equal pain, but Christabel showed no such emotion.

On her return to London, it seems that Sylvia invited Adela to join her in the East End movement. According to Adela, interestingly (if her account is to be relied on) Sylvia told her that in fact it was she who had cut herself off from the WSPU and not vice versa. Adela had been travelling on the Continent with a family friend as a companion-governess, a job Mrs Pankhurst considered demeaning and therefore put a stop to. Even so, Adela did not want to do anything to hurt her mother and consequently refused Sylvia’s suggestion.

It was not long before Adela herself made the painful journey to Paris and, like Sylvia, experienced rejection. Being a committed socialist, she had already been forbidden (by Annie Kenney) to speak in England, but her story is best told in her own words:

I saw mother and Christabel in Paris … mother was against me. She seemed to think I was a great failure. I was ashamed to tell her how hard things were and curiously, perhaps, I did not explain that I had an offer of a post at Chester the following March to teach gardening in a boys’ school. Mother seemed to think I had not tried to get work and wanted to come into the movement as Christabel’s rival.

As it was, Adela was subjected to a torrent of long-harboured complaints from Christabel, although they seem to have been of a peculiarly petty and personal nature. Of course, Adela’s ideals were, at this stage, far closer to those of Sylvia than was comfortable for Emmeline and Christabel, who were afraid that the two girls together might establish a rival organisation. She did not tell her about Sylvia’s attempt to recruit her, nor about her refusal. ‘Had I done so she and Christabel would probably have thought better about me,’ she said.

All those childhood grudges, nursed over the years of isolation and hostility, emerged that day in Paris. Adela seems to have somewhat unfairly blamed Sylvia for all her ills, a bitterness she carried to the end of her life. At the age of only 28, Adela was utterly demolished: there was no fight left in her. ‘It appeared to me quite right that my indiscretions should banish me from my country,’ she wrote. It was suggested that Adela would fare better in Australia:

I was very miserable but down in the bottom of my heart, hope was stirring. I felt that I was not such a fool or a knave as I had been made out and that in another country I should find my feet and happiness. Nothing would have induced me to enter a fight with Sylvia and the rest of the family and my mother’s action in getting me out of the way was best for myself and all concerned. She gave me what money she could spare – it was very little and I often wondered what she thought I would do in Australia when it was spent.

I was young and she was old. Our points of view could not be the same. Tolerance was certainly not to be learned in the school in which she had been trained. If she had been tolerant and broadminded she could not have been leader of the Suffragettes. She had nearly forgotten me as a daughter … and I must confess I had largely forgotten her as a mother … It was part of the price paid by us for votes for British women …

Emmeline, for her part, wrote to Ethel Smyth afterwards, ‘I have pangs of maternal weakness but I harden my heart.’ On 2 February 1914, Adela sailed, alone, on the Geelong for Canberra. She did not see her mother or sisters again.

There was considerable irritation amongst East London members when Sylvia told them of the expulsion. They resented their ejection from the WSPU. However, when it was proposed to change the name of the East London Federation to the East London Federation of Suffragettes, after yet another bitter exchange of letters, Emmeline wrote, with some justification, ‘As for the name, Christabel and I do not approve of the one you suggest because the name “Suffragettes” would be altogether misleading to the public. The WSPU and “The Suffragettes” have become interchangeable terms.’ She said that if Sylvia insisted on the ‘East London Federation of Suffragettes’ – ELFS – she would not carry reports of her activities in The Suffragette. She then suggested a number of alternatives, such as the ‘East London Federation for the Vote’,’ East London Women’s Franchise Federation’ or ‘East London Working Women’s Union for the Vote’. None of these appealed to the women in Bow and they decided to defy Emmeline and become the ELFS, adding bright red for liberty to the WSPU colours of purple, white and green.

With independence declared, the ELFS decided to launch a newspaper. The WSPU journal The Suffragette and the Pethick-Lawrence’s paper Votes for Women were devoted only to a single campaign and their circulation was declining. The name chosen by the ELFS was the Woman’s Dreadnought75. The irony was not lost on her that the rivalry between Germany and Britain focused on building bigger and better battleships, now known colloquially as dreadnoughts. It was not Sylvia’s favourite name but she accepted the majority vote. The paper, which was to focus on a wide range of women’s interest issues, was to pay for itself by advertisements and donations.

Launching a newspaper is an all-consuming business and finding a publisher is not easy. J.E. Francis at the Athenaeum Press, a good friend to the Suffragettes, wrote advisedly to Sylvia on 13 February 1914:

Personally I am not really anxious to print your paper because it will mean I shall have to read every word of it … but I have got the idea that your paper ought to come out and if I can help the issue of necessary information and, at the same time, give work to some very splendid people I must not be deterred by the trouble it will give myself. No doubt the end will be that we shall quarrel and you will take the paper away somewhere else because I cannot make you see my point of view about something you want inserted and I cannot see your point of view as to the necessity of its going in and so insist on it being taken out.

What foresight, for they ran into trouble in the first issue, when Sylvia included a statement by Ethel Moorhead, the first Scottish prisoner to be force-fed. It was omitted by Mr Francis because, he argued, the government had not been given time to reply. Sylvia immediately removed the Dreadnought to an East End printer, although her friendship with Mr Francis survived and he undertook the printing again some years later.

Despite Zelie Emerson’s best efforts, shopkeepers were reluctant to take advertising space and, in the end, only the manufacturers of Neave’s Food and Upton’s Cocoa signed a three-month contract. The paper was to be sold for one halfpenny for the first four days after publication and then distributed free door to door. The first eight-page issue appeared on 8 March 1914; the Dreadnought then ran until July 1924. Sylvia always encouraged her East Enders to contribute as she valued their ideas and views, and did her best to edit their contributions sensitively, in order not to destroy their vitality and originality. The paper was their voice.

For Sylvia, the commitment of the newspaper and the campaign as a whole prevented her from attempting to earn a living from painting, and even writing became more difficult. There was now no longer the possibility of denying the family feud and the press made the most of Sylvia’s expulsion. She had always adopted the WSPU motto of ‘Deeds not Words’ and had never voiced her private criticism of the way the campaign was conducted. Now she was on her own and discretion was hardly an option.

There is a delightful exchange of letters between Norah Smyth and the New York Times. The paper was eager for a full-blooded, 1,000-word attack by Sylvia on the WSPU, and for her to claim that ‘the WSPU is disorganised and crippled financially, that the ‘Cat and Mouse’ Bill has practically crushed the militant movement and any other points she may desire’. A week later, the editor, Ernest Marshall, returned the article, since ‘it does not contain the material we requested and consequently is of no use to us’.

Sylvia certainly ploughed back whatever journalistic earnings came her way, but it was Norah who, over the years, gave most of her inheritance to the ELFS and their many projects. She was a remarkable woman, intelligent, shy, efficient, remembered by friends in later life, when she lived in Malta, as a much loved, tender-hearted eccentric with a collection of stray cats called Tristan and Isolde, Thisbe and Pyramon, Oedipuss and Midas. She had one blue eye and one brown, wore her hair cropped short, in the fashion of the day, and men’s brogues several sizes too big. It was Sylvia’s good fortune that she gathered men and women of Norah’s calibre around her. Nellie Cressall used to say, ‘It’s all your money we’re using’, and Norah would reply, ‘I don’t mind, it’s in a good cause’. Henry Harben was a tower of strength, too, regularly lending money to help with the acquisition or restoration of premises.

When Emmeline returned to England on 10 February, she and Sylvia embarked on a parallel series of public speaking appearances. These often ended in prison, but although they were each in and out of Holloway at the same time, they never met. As Martin Pugh notes, ‘Sylvia … had begun to eclipse her mother by the sheer spectacle of her clashes with the police’. One of these involved being carried in procession shoulder high on a collapsed wheelchair. While in prison, Sylvia had planned to lead the ELFS in procession to Westminster Abbey for the service on Mothering Sunday, 22 March. Released on 14 March, she wrote to the Dean of Westminster explaining their intention and asking him to include a reference to votes for women in the service. Sylvia’s agnosticism did not affect her sense of theatre.

There was consternation in Bow because Sylvia was known to be extremely weak and members were naturally worried that she could not cope with the strain of such a journey. It is about six miles from Bow to Westminster. They borrowed a spinal chair for her from the Cripples’ Institute but, in the crush of people, it buckled. Not to be deterred, Sylvia was hoisted, still sitting, symbolically saint-like, above the crowd and carried, shoulder-high, to the Abbey with the rebel priest, the Reverend C.A. Wills, leading the way. Again, symbolically, the Abbey gates were shut and the marchers, who now numbered several thousand, were told there was no room for them. So Mr Wills conducted his own service outside and Sylvia, high on adrenalin, reported, ‘all pain had left me’. But on the way home in a hired ambulance, once the excitement was over, she was violently sick.

Sylvia used her nine imprisonments between February and June 1914 to create an imaginative programme for the future of the ELFS. Her long-term vision was for a re-housed East End in centrally heated homes, with a communal nursery and playground for the children. In the shorter term, she planned a no-vote, no-rent strike, but was sympathetic to the natural fear of East Enders who could consequently lose their homes. She realised that, in fact, only a crisis would provoke such drastic action; she did not know how imminent that crisis was.

Meanwhile, in what appears to have been a desperate last stand to defend her now shaky power-base, Christabel wrote a series of extraordinary articles, which were then produced as a book, The Great Scourge. The ‘scourge’ was venereal disease, from which, she claimed, 80 per cent of British men suffered. ‘Therefore, marriage is best avoided. Votes for Women – Chastity for Men!’ was her new message; it also marked the beginning of her interest in religion.

Sylvia received an invitation to speak in Budapest at Easter, where the Pankhurst name was known and revered. All expenses and a proportion of the proceeds were to be paid, which permitted Sylvia to take Zelie as a companion. Almost on the spur of the moment, she decided to call on Christabel as they passed through Paris and arrived, unannounced, at the apartment in the Rue de la Grande Armée. Christabel was out, but the maid greeted the visitors with almost hysterical excitement, having seen Sylvia in cinema newsreels. She rushed off to prepare a meal while they waited. Christabel was less enthusiastic, embarrassingly remote and uninterested in their Hungarian trip. Sylvia realised that the fiery, protective Zelie was about to explode, and, although they had a long wait before their train was due, they left without eating.

Both Zelie and Sylvia were ill and still suffering from the after-effects of their prison experiences. They barely coped with the arduous journey, supporting each other as best they could. ‘Though I was temporarily the weaker the afflictions of my companion were the graver,’ Sylvia wrote. Her recollections of that journey are as detailed and sensitive as those of her travels in America, although there is additional warmth in her writing. She clearly loved the countryside and its people. Easter Sunday found Zelie and Sylvia, absorbing the atmosphere of the incense and the bells in the ‘gorgeous’ bronze and gold basilica, where they listened to the preacher declaiming against socialism. Then they travelled with friends on a sightseeing tour of the city, enjoying the colour, the gaiety and the fashions. In a newly developed showcase suburb for 30,000 people, Sylvia saw how her vision for the East End of London could be realised, and was overwhelmed there by the state provision for orphaned and destitute children. On the other hand, the women’s prison was worse than Holloway:

So dejected they looked and one was so hopelessly sorrowful that I was constrained to take her hand, miserably wishing that I had the power to help her. She burst into shuddering sobs. I guided her to a bench, then saw that all the others were weeping too … They seized my hands, trying to kiss them; even the girl in the bed stretched out her arms. Distressed that I had occasioned their tears I pressed their hands, poor children but would not let them touch mine with their lips: their humility grieved and embarrassed me. As we left them, the suffrage ladies told me they would think I had scorned their kisses. I knew of nothing to dispel that thought save to blow kisses to them from the door.

A large audience gathered for Sylvia’s meeting in the great hall of the Vigado. She told them of the struggle by British women for the vote and was warmly praised for the ‘incredible greatness’ of the hunger strikers in their heroic fight ‘for human freedom’.

From Budapest the couple went on to Vienna, where they were filmed and fêted, taken to see Die Walküre from a box at the Opera House and out to walk in the peace of the Vienna Woods. They gathered violets among the beeches, where Sylvia said she felt like a caged wild thing, liberated among the trees. ‘Poor town-bred children: what joys you miss!’

While Sylvia was away, the ILP hosted a major celebration of its twenty-first birthday, which was attended by Lillie, and during which Hardie gave her an extraordinary and unexpected accolade. Waiting for the applause to subside, he looked back to the foundation of the ILP: ‘Never, even in those days, did she offer one word of reproof. Many a bitter tear she shed but one of the proud boasts of my life is to be able to say that if she has suffered much in health and spirit, never has she reproached me for what I have done for the cause I loved’.

Arriving back in Bow after the European visit, Sylvia was extremely worried by Zelie’s appearance, ‘her face nervously strained, her figure shrunk’. The campaigns were taking their toll. However, there was a positive development: before leaving for Europe, Sylvia had taken a walk in dense fog one morning and come across a large empty house, 400 Old Ford Road. Previously it had been a school, then a factory and had a hall capable of seating about 300, which was connected to the main house by a smaller flat-roofed hall.

With yet more financial support from Henry Harben, and the usual practical help from the community, the women set to work. A supportive all-male group had sprung up, known as The Rebels Social and Political Union. They helped, and between them all, the building was painted, decorated and restored to make the HQ of the ELFS and a home for Norah, Sylvia and the Paynes. Amid much bustle and excitement the ELFS organised a library, a choir, lectures, concerts and a ‘Junior Suffragettes Club’. As the ‘Women’s Hall’, it became a focus and a home for anyone in need. The housewarming was on 5 May, and the next day, Zelie Emerson, very reluctantly, set off back to America. Sylvia had been advised by doctors that Zelie must return if she was to recover from her fractured skull and force-feeding. But it took many hours of painful, distressing persuasion by Sylvia to win Zelie’s agreement.

Roughly a year after the parting, Zelie wrote to her from America enclosing a poem that indicated there may have been something more than a platonic friendship:

Dear Sylvia, I have not heard from you so I conclude that you do not wish to see me. However I would like to know what was the cause for your not wanting me to speak for us any more …

I know that I am a ‘self righteous little prig’ but would like to know what else I am to you …

Of course you know that nothing that has happened or may happen between us can ever alter my feeling toward you and perhaps some day … I may be of service to you and the cause for that is after all the only thing that really matters …

To Sylvia Pankhurst

You did not understand, and in your eyes

I saw a vague surprise,

As if my voice came from some distant sphere,

Too far for you to hear:

Alas! In other days it was not so

Those days of long ago

II

Time was when all my being was thrown wide

All veils were drawn aside

That you might enter anywhere at will

Now all is hushed and still

Save for a sound recurring more and more

The shutting of a door

As ever. Yours Zelie Emerson.

Thanks for the hair.

The political tension on both home and foreign fronts was becoming increasingly alarming, although for the people in the East End, the likelihood of war in Europe still seemed remote and strangely unreal. Hardie was doing his best to ‘alert the still slumbering millions of the danger of drifting into war’.

In Ireland, despite improvements to be brought about by the proposed Home Rule Bill, the enmity between Catholics and Protestants was as bitter as ever. Both sides had established private armies. Civil war loomed. Any hopes that women held of winning the vote were dashed in the midst of all this. A deputation from Belfast went to see Sir Edward Carson, leader of the Ulster Unionists, and sat on his doorstep through an entire weekend until he agreed to meet them. They were disappointed. Sir Edward refused to introduce the issue of the promised votes for Ulster women. The result was the first major uprising of Ulster Suffragettes. Bombs exploded and buildings were set on fire, and, when the leaders were arrested and charged with possession of firearms, they demanded to know why Sir Edward and his colleagues had not been arrested too. They were as guilty of violence as the women.

In Europe, while the naval race was escalating, Britain formed a buffer alliance known as the Triple Entente. Austria, Turkey, Bulgaria and the Balkans were all tussling with conflicting aims and ambitions of their own, and edging closer towards Germany. Consequently, at home, as Sylvia said, ‘Changes the Gladstonian era would have deemed remarkable were passing through Parliament with scant public notice’. The Parliament Act, which removed the Lords’ ultimate right to veto legislation was passed in the Commons; the Trades Union Act and the disestablishment of the Welsh Church now seemed trivial.

Christabel, still commanding her troops from Paris, was writing strident letters to Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, who had told her that her place should be in London. Christabel replied, ‘You know anti-militancy does affect the reasoning faculty adversely. People who are most rational and logical and enlightened when their political movements are at stake, suddenly lose their bearings when weak. It is the weakness of the pro-suffragists that is the enemy now’. That spring she had launched an unprecedented campaign of destruction. In the first seven months of 1914, three Scottish castles were destroyed in one night, the Carnegie Library in Birmingham was burnt, the Rokeby Venus was slashed, as was a portrait of Thomas Carlyle by Millais in London’s National Portrait Gallery. Stately homes all over the British Isles were attacked and, among many other incidents, railway stations, piers, sports pavilions and haystacks were damaged. A bomb was exploded in Westminster Abbey and £2,000 worth of flood damage was done to the great Albert Hall organ. Churchmen referred to ‘unparalleled wickedness’ and ‘infamous crimes’ and many women were themselves injured in the disturbances.

Sylvia, still refusing to use arson or attack property or works of art, was active as ever in her own way. She organised a huge May Day event in Victoria Park. In the centre of a group of twenty women chained to each other, she arrived at the Park where banners and maypoles were being erected. The police charged, hitting out with truncheons and eventually smashing the padlocked chains. Sylvia was flung onto the floor of a taxi, followed by four officers who leapt in swearing, pinching and arm-twisting. This time in Holloway, she determined that the next deputation to Asquith must be an elected group of working people from the East End, in order to prove that the demand for the vote was indeed both democratic and of the masses.

Freed on 30 May, she wrote to the Prime Minister asking him to receive a deputation elected by open rallies to be held in the East End. The rallies would also vote on the demand they preferred: without exception, they unanimously selected ‘a vote for every woman over 21’.

He refused. She wrote again, explaining that a large proportion of the women of the East End who were enduring terrible hardships were ‘impatient to take a constitutional part in moulding the conditions under which they have to live’. She told him she regarded the deputation of such importance that if he refused to meet it, she would not only refuse food and water in Holloway when, most likely, she was re-arrested, she would also continue her strike outside the House of Commons when she was released. Asquith again refused. When Sylvia told the last rally meeting of Asquith’s refusal and of her intention to carry out the threat, women were in tears.

The Suffragettes lost a lot of public support with their campaign of vandalism and destruction, including bombing Westminster Abbey. Sylvia did not get involved with such attacks.

On the evening of 10 June, ‘The whole district was aroused; the roadway thronged. The Rev. Wills asked to be allowed to say a prayer from the window. We knew he was jeopardising his career and respected his courage. I looked out on the throng … men with bared heads and the women with streaming tears.’ Sylvia was clearly too weak to walk to Westminster, so was carried on a stretcher by four bearers, including H.W. Nevinson. Not long after the procession had started, police charged, Sylvia was thrown to the ground and, within minutes, she was back in Holloway. The marchers re-formed and continued to Parliament Square without her. The elected deputation of nine women and three men was finally allowed inside the House. They were told that the Prime Minister was away but would be given their message. The women made speeches in the forbidden ground of Parliament Square and no one was arrested.

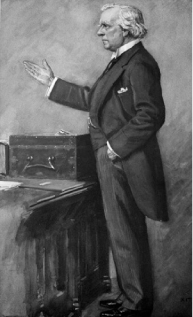

Herbert Henry Asquith, the Prime Minister, refused to meet the Suffragettes. From an illustration by XIT in Vanity Fair.

On 11 June, the Commons debated the hunger strikes and Home Secretary Reginald McKenna referred to ‘a phenomenon absolutely without precedent in our history’. He decided that patient and determined action would be best, and that he would consider criminal charges against the WSPU subscribers and so intimidate them into capitulation. Asquith continued to refuse the East Enders their audience. Norah Smyth, fearing Asquith would let Sylvia die, wrote to Emmeline, begging her to link the WSPU efforts to those of the ELFS. Emmeline replied, ‘Your action is not in conformity with WSPU policy and tell Sylvia I advise her, when she comes out of prison, to go home and let her friends take care of her’.

On 18 June, Sylvia was released, weak and in pain after her latest hunger strike. It was already dusk when she persuaded Norah to drive her immediately to the House of Commons, where a small group of women was waiting. Josiah Wedgwood and Keir Hardie were there too, kind and caring and clearly troubled at her condition. Keir tried to contact the Prime Minister and, when he returned, it was only to confirm that as she was blacklisted for having thrown her missile at the Speaker’s picture, she must write to him, apologising for having ‘broken the rules of the House’.

She agreed but then insisted that her friends lay her on the ground, near the statue of Oliver Cromwell where, she said, she would stay without eating or drinking until she died, or until Mr Asquith agreed to see the East End deputation. Nevinson described the scene later. ‘I stood beside her, very helpless, while she lay on the steps, apparently dying, and the police, perhaps in pity, hesitated to drive her away. At last, to my infinite relief Keir Hardie came out of the House and on hearing from me what the situation was stood with me.’ George Lansbury joined them and the three men went immediately to see the Prime Minister, returning jubilant with the news that Asquith had relented. He agreed to see six of the delegates on the following Saturday, 20 June.

‘Everyone was laughing and talking around me.’ Was this the turning of the tide? Next day, Sylvia prepared a statement. She felt this was an opportunity for the people from Bow to speak for themselves. Those who were the elected representatives were led by Julia Scurr, whose husband John later became an MP. There was stout, old Mrs Savoy, the brush maker, ‘always jolly despite her dropsy and palpitations’, whom George Lansbury described as ‘the best woman in Old Ford’; motherly, ancient Mrs Payne; Mrs Bird, mother of six, living on her husband’s wage of £1 5s weekly; Mrs Watkins; and frail little Mrs Parsons. They told their harrowing stories to a startled and softening Asquith. He was surprisingly impressed and praised the way in which they were conducting their campaign with clarity and without resort to ‘criminal methods’. He said, ‘I think it is a very a moderate and well-reasoned presentation of your case and I will give it, you may be quite sure, very careful and mature consideration.’ He also declared, ‘if you are going to give the franchise to women, you must give it to them on the same terms that you do to men … That is, make it a democratic measure … If the change has to come, we must face it boldly, and make it thoroughgoing and democratic in its basis’.

This was the nearest Sylvia had ever come to a vote of confidence, and the press also agreed that women’s suffrage could not long be delayed. The women from the East End had achieved a breakthrough on the strength of their presentation, but, as they all agreed, it was Sylvia who had brought them to this moment.

With a General Election likely before the end of the year, Sylvia and Prime Minister Asquith were in general harmony on the best way to approach the question of suffrage – and it was not Emmeline or Christabel’s way.

George Lansbury then arranged a breakfast meeting between Sylvia, himself and Lloyd George in the Commons. Money-conscious as ever, she took the lengthy bus trip from Bow to Parliament rather than choose the extravagance of a cab. By the time she arrived, still unwell, she was extremely tired, the light behind Lloyd George hurt her eyes and she immediately feared that the meeting was doomed. Besides, she noted, Lloyd George was far too quick a thinker for Lansbury.

Lloyd George told them that he would indeed put his weight behind a Reform Bill, which would include women’s enfranchisement and an offer to resign if he failed. His backing would be conditional on the end of militancy. Sylvia admitted later that she should perhaps have asked for a written guarantee, but instead she made a serious tactical error. She said that she doubted Christabel would agree to a truce, short of a government measure. He replied curtly that he would debate the matter only with Christabel herself.

George Lansbury interpreted the meeting rather more positively than Sylvia, who feared no certain promises had, in fact, been given, and he communicated his enthusiastic excitement immediately to Christabel. She responded, just as Sylvia had anticipated. No truce. So Sylvia wrote to her sister, offering to visit Paris and relay her own impression of the meeting. The reply was a telegram from Christabel to Norah: ‘tell your friend not to come’. Christabel was becoming irritated by her younger sister’s increased influence with MPs and the respect with which she was apparently now being treated.

The following weekend in late July, Sylvia and Norah went down to Penshurst in Kent, near her favourite Cinder Hill, where they booked into the local hotel under assumed names. But Keir Hardie blundered by sending a telegram to ‘Pankhurst’, thus exposing their cover and causing the innkeeper much anxiety. He begged the two women to remove their ELFS badges: his landlord, Lord de Lisle, would be angry if he gave them shelter, as Suffragettes had recently attacked his home, Penshurst Place. Hardie eventually joined Sylvia and Norah and, after much discussion, agreed to urge that Adult Manhood and Womanhood Suffrage should be the Labour Party’s main plank at the coming election. Everything appeared to be coming together very well.

It is arguable that, had it not been for the war, Sylvia, the Pankhurst who through a combination of militant courageous action and a belief in democracy and debate, would have at long last brought the women’s movement closer to success than it had ever been. But it was not to be.

On 22 July, Emmeline, weak and exhausted, escaped across the Channel to join Christabel in Brittany. On 26 July, Sylvia and the ELFS members went out for a picnic among the hornbeams and beeches of Epping Forest. On 28 July, Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty, wrote to Clementine, ‘My darling One and beautiful. Everything tends towards catastrophe and collapse … I am interested, geared up and happy. Is it not horrible to be built like that? … I wondered whether those stupid Kings and Emperors cd not assemble together and revivify Kingship by saving the nations from hell, but we all drift on in a kind of dull cataleptic trance. As if it was someone else’s operation!’ At the end of July, Sylvia left for Ireland to investigate the troubles there.

A month earlier, on 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne had been assassinated, with his wife, in Sarajevo by a Serbian secret society known as the Black Hand. The Serbs, Slav by race, were allied to Russia and historically friendly with France. Austria’s ally was Germany. Britain was still wavering in her loyalties, since the King was inconveniently cousin to Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany, the Russian Tsar and the Austrian Emperor, but was increasingly anxious about German ambitions.

The murder of Archduke Franz Ferdinand had provided the spark to light a fuse but it was barely noticed in a British press more occupied with domestic events in Ireland. Austria had declared war on Serbia in June. Russia was then automatically drawn in. Finally, on 3 August, when Germany invaded neutral, ‘gallant little’ Belgium as part of their designs on France, Britain was left with no option. Such a small country as Belgium had to be protected.

The Assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand led to the First World War and changed the shape of the world, including the role of women.

On 3 August, in the House of Commons, Keir Hardie, who was already being attacked for his pacifist views, spoke bitterly against the war. He warned of the terrible suffering it would bring to the poor. Caroline Benn describes how, while he spoke, he felt ‘a cold, cold wind behind his back’. It was the sound of the National Anthem being quietly sung across all parties.

And so it was, that, on 4 August 1914, Britain declared war on Germany.

_________

74.The sack.

75.HMS Dreadnought was the world’s largest, fastest battleship, launched in February 1906.