Chapter 4

The Foreign Legion

The world’s most perfect woman

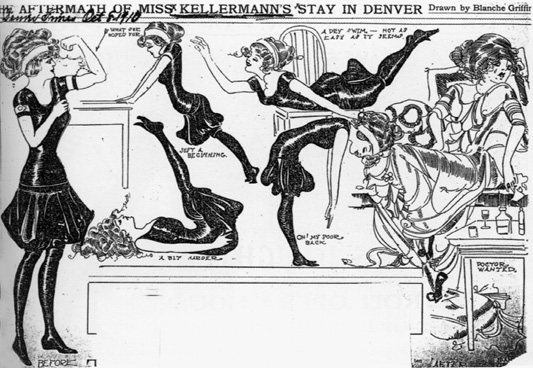

Professor Dudley Sargent of Harvard University, having completed his scientific research – running a measuring tape around 10,000 women – felt confident in his announcement that he had at last found the perfect female body.

It belonged, he reported, to ‘a model for all young women for her beauty of outline and artistic proportions’. Sargent didn’t have time to wait for the drum roll, and he had the good sense not to.

Who was she?

‘I will say without qualification that Miss Kellerman embodies all the physical attributes that most of us demand in the Perfect Woman.’

Annette Kellerman was the most famous Australian of her day. She was Kylie, she was Elle, she was Germaine, she was Nicole. She was Cathy Freeman. And she was all of them in one: the world’s most acclaimed female athlete and a show business superstar, Annette Kellerman was for a substantial period of the 20th century the most famous Australian woman the world had known. Yet, when she died three decades ago, Annette Kellerman was remembered perfunctorily as the Australian who had invented the women’s one-piece swimsuit; and wasn’t there something about her making movies?

She deserved better. Apart from being Australia’s first movie star and a swimmer who could beat the best women – and some of the best men – in the world, Annette Kellerman was, unquestionably, a great pioneer of the women’s movement, perhaps 70 years ahead of her time. Of course that meant she came in for some sharp criticism. She may well have been pronounced ‘The World’s Most Perfect Woman’ but there were many who thought her the World’s Wickedest Woman.

Annette Marie Sarah Kellerman was born in Marrickville, Sydney, in 1886. She was the daughter of Frederick Kellerman, an Australian violinist, and Alice Charbonnet, his French wife, a pianist and music teacher. As a child, she was encouraged to take up swimming to strengthen her legs. Crippled by polio, she swam, as the cliché has it, like a fish: by the time she was 16, she was swimming among them twice daily at the Melbourne Aquarium and getting paid the considerable sum of £5 a week to do so.

Annette’s father took her to London. They were going to make their fortune. She was a flop. No-one showed the least interest in a girl from the Antipodes who could swim. Then, as a publicity stunt, Annette swam 15 miles up the Thames River and the press and promoters from all over Europe scrambled. The Daily Mail sponsored her in an attempt to swim the English Channel, but a month later, in Paris, the only woman competitor, Annette made headlines when she competed in a 12-kilometre race down the Seine. Seventeen men started beside her, but there were only four swimmers who finished, and only two finished in front of her.

In June 1906 Annette tried a third time – and just failed – to swim the Channel, and the Prince of Wales, a man famously fascinated by the female form, asked her to give an exhibition of her swimming at the London Bath Club. Annette agreed – provided she could wear the costume she had used in her Channel attempt.

She was still a teenager, vibrant, fresh and attractive and her one-piece swimsuit – she stitched black stockings into a boy’s costume – revealed her slim, athletic body, unusual for the time, when the measure of a desirable woman was her plumpness. The middle class was scandalised but the future King, whose mistresses included Lily Langtry and almost all the great courtesans of France, was delighted. Annette’s fame was assured, and women’s swimwear, which until then had consisted of smocks and stockings designed to obscure the female form, was about to change forever.

She did a brief season at the London Hippodrome – by now she had a vaudeville act that consisted of aquatic feats and was later to encompass acrobatics, wire walking, singing and ballet dancing before mirrors – and later that year went to America.

She was a sensation. For a huge fee, $1250 a week, the 20-year-old ‘Australian Mermaid,’ swam in a glass tank at the White City fairgrounds in Chicago, then Boston and New York. A year later she won priceless press coverage when she was arrested on Boston beach for wearing a brief one-piece swimsuit. She won the landmark case and changed the design of women’s swimsuits irrevocably.

Annette took her show to the leading theatres in the US, Europe and Australia, married her agent in 1912 and then went, inevitably, to Hollywood.

She starred in several films. In one, she had to dive 28 metres from a cliff-top into the sea, a world record for a woman. In Daughter of the Gods, the first film with a $1 million budget, she had to dive 19 metres into a pool filled with crocodiles. A ladder was out of camera range and, Annette later recalled, ‘I dived under those crocs and was up that ladder before you could say snap!’

When Harvard’s Professor Sargent, encouraging healthy exercise, announced after a much-publicised search that Annette was ‘the perfect woman’, she became one of the world’s best-known performers and in such demand from rival studios and theatrical promoters that she could afford to turn down a five-picture deal with 20th Century Fox. (The professor, using graphs and charts demonstrated that Annette Kellerman’s dimensions approximated those of the Venus de Milo. She herself didn’t fully agree with the professor. She was perfect, she said, ‘only from the neck down’.)

Annette Kellerman was a lifelong advocate of exercise and diet. Her corset-free curves, a revelation in 1910, were a harbinger of the feminists’ Burn the Bra call 60 years later.

Three decades later she was the subject of a Hollywood bio-pic very loosely based on her life, The Million Dollar Mermaid, with Esther Williams. Although she was a consultant on the movie, she didn’t care for it, calling it ‘namby-pamby’ and it clearly failed to capture the kaleidoscopic personality that was Annette Kellerman. She seemed to be able to do it all: a dazzling performer on the high-wire, a ballet dancer, a tough competitor on the tennis court, an accomplished linguist, a songwriter. Above all she was a propagandist for the joys of life: ‘If only you could know what it is to walk and work and play and feel every inch of you rejoicing in glorious buoyant life.’ A vegetarian, her attitudes to health and beauty anticipated today’s attitudes and she was a forthright advocate for the cause of women left at home with children.

For more than 50 years she gave lecture tours on health and beauty and wrote books on the subject before she returned to Australia to live on the Gold Coast in 1970.

Annette Kellerman died aged 89 in Southport on 6 November 1975, in the week of the dismissal of the Whitlam government. For once in her life she couldn’t grab the headlines.

All my life I have tried to find my mother, and I have never found her. My father has not been Theodore Flynn, exactly, but a will-o’-the-wisp just beyond, whom I have chased and hunted to see him smile upon me, and I shall never find my true father, for the father I wanted to find was what I might become, but this shall never be, because inside of me there is a young man of New Guinea, who had other things in mind for himself besides achieving phallic symbolism in human form.

— From My Wicked, Wicked Ways

If Errol Flynn had not existed, the devil would have had to invent him.

In fact, he was invented in the character of Flashman, the villain of one of Victorian literature’s classic ripping yarns for boys, Thomas Hughes’ Tom Brown’s Schooldays. In it, Flashman, the sadist of the fifth form, roasts young Tom over the fire in his study. It may have been the late 18th century, and the school may have been Rugby, but it just wasn’t cricket to toast your fag. Flashman – the rotter! – gets sent down for his sins. After that he’s hardly heard from and Tom Brown’s Schooldays becomes exceedingly boring.

Then, in the 1970s, George MacDonald Fraser resurrected Hughes’ delicious villain and made Flashman the centrepiece of a dozen historical adventure novels. In all of them, whether rolling in the sweaty embrace of the cruel Queen of Madagascar, whimpering with fear in the fetid dungeons of the insane tyrant of Abyssinia, or inadvertently starting the Charge of the Light Brigade (with a thunderous and frightening fart induced by too much champagne the previous night), Flashman always has one eye for the ladies and the other for the main chance. He invariably behaves in a downright despicable way, only to emerge, skintight jodhpurs tattered, wrists still red raw from the ropes that bound them, with his reputation intact, unsullied – enhanced!

Flashman’s attitude to women is always appalling. ‘He’s a monster,’ says George MacDonald Fraser. ‘You must remember he raped a girl in the first book; since then he’s never needed to.’

Did George MacDonald Fraser have anyone in mind when he resurrected Flashman? ‘David Niven was keen to play him,’ MacDonald Fraser once said, ‘He would have made a wonderful Flashman. Or his friend Errol Flynn, who had that shifty quality.’

He got it half right. David Niven would have been excellent acting in the role of Flashman and he was a fine actor. But Flynn, the actor, got his finest reviews in the last years of his life when he played himself. Flynn was Flashman.

Flynn himself said that ‘few others alive in the present century have taken into their maw more of the world’, and it’s true that even Flashman, and the characters Flynn played on the screen – Robin Hood, Don Juan, Captain Blood or General Custer – might have bitten off more than they could chew when it came to playing the real life man, Errol Flynn.

Like Flashman, he was a devil with the women and a peerless cad. But even the fictional Flashman would be hard put to rival the remainder of Flynn’s CV. Flynn was a man who beat a murder charge and three charges of the rape of underage girls. He was a con man, a brawler, a drunk, a drug addict, a gigolo, a congenital liar, a slave trader, a thief, a man who fought off cannibal headhunters, went to the Spanish Civil War – just to see it, not caring who won – and gave the world the wink, wink, nudge, nudge phrase, ‘In like Flynn’.

In short, an absolute shower! But when you understand his beginnings you realise Errol Flynn wasn’t the devil incarnate: he was just a very naughty boy.

Once you get to that point of understanding it’s hard to resist him. He was, at heart, a boy who grew up looking for trouble, an Australian larrikin who went on to become a deeply troubled man, racked by insecurity and his strong sense that he had wasted his life. It’s true that Errol Flynn was, in the last decade of his life, a parody of himself – a man addicted to drugs, alcohol and sex. But it’s also true that, right to his pathetic end, he retained an essential decency.

Many didn’t see it that way of course. Among them, significantly, was his mother.

According to Marelle Flynn, he was a naughty boy almost from the day she gave birth to him, Errol Leslie Thomson Flynn, on 20 June 1909 in Hobart.

He was descended on her side from Richmond Young, a midshipman who joined the mutiny on Captain Bligh’s HMS Bounty. Flynn, ironically, was to make his screen debut in the role of the man who led the mutiny, Richmond Young’s friend, Fletcher Christian. Another of his ancestors, his mother said, was her uncle, Robert Young, a ‘blackbirder’ cooked and eaten by South Seas cannibals. (In New Guinea, Flynn dabbled in the form of slave trading euphemistically known as blackbirding and several times, he says, came across the horrific remains of cannibal feasts.)

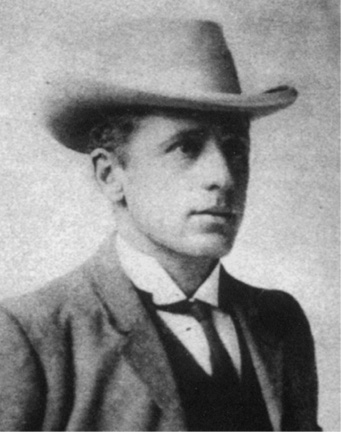

His father’s side was much more prosaic. The emigrant Flynn family had a history of poverty in Ireland: one was hanged for sheep stealing. Errol’s father, Theodore Leslie Thomson Flynn, tall and straight in every way, was a highly respected boffin: a lecturer, and later Professor of Biology at Hobart’s University of Tasmania, who went on to get an MBE and an entry in Britain’s Who’s Who for his work at Queen’s University Belfast. There was nothing out of the ordinary about Theodore apart from a theatrical way of giving lectures to his students, and his international eminence in the field of marine biology.

Errol’s mother, however, was altogether another fish. Lily Mary (Marelle) Young was beautiful – a stunner – who refused to breastfeed her baby because she didn’t want to ruin the line of her bosom – an aesthetic concern that Errol, not so many years later, would perfectly understand. The apple didn’t fall very far from the tree.

According to Errol, Marelle was unfaithful to Theodore, certainly later in her life in Paris. There, he implied, she had an affair with the Aga Khan among others. Professor Flynn spent much of his time from 1930 in Antarctica, England and Northern Ireland and Marelle preferred France. An intriguing cocktail of self-centred extrovert and uptight Anglican stirred with a dash of the disciplinary traditions of the 18th century British Navy and shaken with the jazz soundtrack of the Roaring Twenties, Marelle Young was probably not cut out to be anyone’s mother, certainly not Errol’s. The two fought from the time he could toddle. He was an intelligent, precocious child, articulate, questioning and stubborn. She was an adult. She punished Errol with slaps or, sometimes, thrashings. He hit back by his refusal to bend to her will or beg for her love.

‘My young, beautiful, impatient mother, with the itch to live – perhaps too much like my own – was a tempest about my ears, as I about hers,’ Errol wrote in his autobiography My Wicked, Wicked Ways, published shortly before his death in 1959.

‘Our war deepened, so that a time came when it was a matter of indifference to me whether I saw her or not. These brawls with her, almost daily occurrences, did something to me. Mostly I wanted to get away from her, get away from home.’

Once, when he was six or seven, he did get away. Playing under a porch with Nerida, a neighbouring little girl, they were surprised by Nerida’s mother. She saw the two small children examining each other’s private parts – the first of many thousands of mutual examinations that Errol would subsequently share. (Twelve to fourteen thousand, was his estimate.)

She mustn’t play that game, Nerida’s mother told her little girl and left it at that. Errol’s mother, on the other hand, became near hysterical with rage, screeched that he was a ‘dirty little brute’, gave him a hiding and demanded he tell his father what he’d done. Instead little Errol ran away from home.

‘We suffered agonies of anxiety for three days and nights,’ Marelle Flynn recalled in a letter. ‘He was found miles away where he went and offered himself for work at a dairy farm. He asked only five shillings a week as wages, saying that would do him, as he “never intended to marry.”’

(Flynn commented when told of this letter. ‘That tells it. I never have married. [In fact he was married three times and had children with all three wives.] I have been tied up with women in one legal situation after another called marriage, but they somehow break up.’)

Mother and son, they spent a lifetime warring. ‘He was a nasty little boy,’ she told reporters at the height of his fame. He had only one word for his mother, the four-letter word rarely used about one’s mother. It was the word of a cad, but clearly much of the sins of Errol Flynn can be laid at Marelle’s feet.

Errol Flynn’s schooldays, unlike goody-goody Tom Brown’s, were marked from beginning to end with rebellion and expulsion. He went to several Hobart schools and was asked to leave each of them after a short stay. At the Hobart High School’s annual fete Errol and the head prefect, ‘a hitherto earnest, dependable type’, dropped ice-creams on to the heads of people below them in the hall and topped things off by smearing treacle on the steering wheel of the headmaster’s car. He left Hobart High ‘unexpectedly’ immediately after, on 16 December 1925. Gone, but not forgotten.

‘Naturally, we his class, followed his future career with great interest,’ a school prefect recalled. ‘His character was dominated by a contempt for convention and a desire to shock. He was the complete egotist. His extreme good looks were spoilt by an incredibly smug expression, plainly seen in his pictures.’

His father took the family to London and the pattern of being expelled from school after school continued. His parents were frequently away and Errol was something of a waif, largely left to fend for himself. But when Professor Flynn came back to Australia, this time to his home town Sydney, his name ensured Errol a place at Shore, one of the nation’s top schools. Without Professor Flynn’s credentials Errol could not possibly have passed the Shore admittance test and Mr Robson, the headmaster, formally cautioned him that he needed to pay attention to his studies. In other matters, however, Errol led the school. He was 16, bigger than almost all his classmates, skilled at tennis, swimming, diving and boxing – he relished a playground scrap – and he was far more worldly. But like boys in those days he was largely ignorant of the mysteries of sex. Here young Errol showed a high aptitude for learning. He gained a girlfriend he was later to become engaged to – ‘Naomi was as naïve about sex as I’ – but his sexual awakening led him to focus on another.

In the index to Amy and Irving Wallace’s The Intimate Sex Lives of Famous People, Errol Flynn gets star billing in a variety of roles:

Men Who Enjoyed Girls 16 Years or Younger; Polygamists; Open Marriages; Sex Trials; Great Lovers & Satyrs; Caught in the Act; Busy Entertainers; Macho Chauvinists; They Paid for What They Got; Endurance and Staying Powers; Voyeurs; Peeping Toms; Practitioners of Oriental Techniques

Elsie, the school’s attractive maid, a woman about 30, would meet Errol behind a hedge below his first floor dormitory window. Errol, naturally, would drop the five metres from the window to the hedge.

Nothing much happened, he says. ‘She used to do a bit of grubbing, but I didn’t know how to open my flies with a lady present.’ Even so, as he pointed out, ‘It was much more interesting than algebra.’

Inevitably he was kicked out of Shore. He was, Mr Robson told him, a disturbing influence on the rest of the scholars (not to mention Elsie). Once again Errol was on his own. His father was in England, his mother in France. He got work through a friend of his father, the manager of Dalgety and Company, the famous shipping and merchandising business and given a job in the mail room sticking stamps on letters. Young Errol enlivened the boredom of it by tickling the petty cash box. He and a workmate, Thomson, took the cash to go to Randwick racecourse, meaning to put the money back once they subtracted it from their winnings. It’s seldom that easy. The likely lads were duly sacked and once again Errol found himself needing somewhere to live and a job.

Thomson introduced him to the Razor Gang – vicious muggers who operated around Kings Cross with a razor-blade embedded in a cork. Errol didn’t fancy that life and when Thomson fell foul of the gang and had his throat slashed Errol thought it healthier to live with three other tramps in the Domain, the inner city park overlooking Sydney Harbour. Arranging his Sydney Morning Herald as he settled into bed one night he saw the front page headline: Gold Strike in New Guinea. Hundreds on the trail. Errol felt he was about to go north, young man.

(Well, that’s how Flynn told it. A much more likely version of this epiphany is that Errol never really got involved in the Razor Gang, nor did he need to sleep in the park. The news that there was a fortune lying around to be picked up in the mountains of New Guinea probably came to him over toast and marmalade and a pot of Bushell’s tea at Grandma’s. In Sydney Errol had two adoring grandmothers, well-off aunts, uncles and cousins, and numerous influential friends of his father.) Whatever the truth, one of them gave him the fare to New Guinea.

In a journal he kept in New Guinea, Errol set out a young man’s pompous but clear manifesto of how he intended to live his life. He had no intention of discovering as he lay dying that he had not lived, he said. Life was not a rehearsal and ‘I shall know it by experience – and not make wistful conjecture about it conjured up by illustrated magazines.’ Ironically, his life was to be the subject of illustrated magazines galore and enough gossip column inches to bury the island of New Britain, his first port of call in 1927.

He was just 18 when he sailed from Sydney to the island off the mainland of New Guinea. Still a teenager, still growing, still a little gawky, and entirely self-centred as he always would be, Errol spent some months there, mostly dancing the Charleston and the foxtrot to the Tropical Troubadours at the Kokopo Hotel in Rabaul and working when he had to in menial jobs. Then he went to the mainland, and got a job as trainee District Officer for the Australian Government. His first rung up this public service ladder was at the very bottom: government sanitation engineer. It lasted until he was found in bed with the Polynesian wife of one of his superiors and the next day he was ordered to accompany District Officer Taylor to Madang, where four prospectors had been killed.

I am going to front the essentials of life to see if I can learn what it has to teach and above all not to discover, when I come to die, that I have not lived.

I am going to live deeply, to acknowledge not one of the so-called social forces which hold our lives in thrall and reduce us to economic dependency.

I am going to live sturdily & Spartan-like, to drive life into a corner and reduce it to its lowest terms and if I find it mean then I shall know its meanness, and if I find it sublime I shall know it by experience – and not make wistful conjecture about it conjured up by illustrated magazines.

From Errol Flynn’s New Guinea notebook, written as a 24-year-old, in 1933, and left behind when he had to skip town.

Flynn once said his mother ‘could stretch a good story’ and here, again, Errol took after her. He carried a copy of the short stories of Jack London with him when he went to New Guinea, and his father would post him books by such authors as Robert Louis Stevenson, R.M. Ballantyne and H.G. Wells; stories of derring-do in tropical islands, often based on fact. Flynn’s account of his New Guinea years should be read in much the same way. It makes it difficult, however, to find the truth of his four and a half turbulent years in New Guinea.

Here, for instance, is Flynn chatting in his carefree, cavalier way, to a Melbourne Argus reporter on 12 September 1936 about ‘The Only Time I Have Ever Been Scared.’ (It’s twice as amusing if you read the account in the drawl of W.C. Fields.)

‘I was ambushed in New Guinea by a tribe of natives with a peeve, or something. They sprang from the jungle, bows and arrows ready. My boys dropped their loads and ran…My gunbearer – he’s usually the last one to stick – dropped my gun and left for parts unknown.

‘Grabbing my trusty pistol I winged one of my attackers on my way out. My only scar is on my shin, and was put there by a poisoned arrow that struck me as I made tracks away from there.

‘I kept on going until I came to a clearing. Pouring rain added to the jolly occasion. There I stayed all night, twisting my head to watch in all directions. The worst of it was that although I had cigarettes I had no matches. Miserable night! A smoke and no way to light it!

‘Next morning my boys came back, sheepishly, finding me drenched and very, very, irritable. They backtracked and got the load – including the matches – and I smoked instantly.’

This colourful account, which might have described a scene from any one of the Tarzan movies then in vogue, is typical of Flynn’s swashbuckling writing style. When famous, he wrote two novels. Precursors to the Mills & Boon school of novel writing, Beam Ends and Showdown are bodice-ripping yarns drenched with action and romance and a hero not a million miles removed from Errol Flynn himself.

In New Guinea he had a brief moment of madness: he considered becoming a lawyer. Errol wrote to his father asking the professor to pay for him to study law at Cambridge, but then, coming to his senses he toyed with the notion of making his living as a writer. He corresponded for the Bulletin from Port Moresby; at the height of his fame wrote his two novels and near the end of his life wrote his autobiography, My Wicked, Wicked Ways.

Mostly, the autobiography, written with Earl Conrad, is an amusing, wry and factual story, but the New Guinea chapters – the most obscure yet undoubtedly the most colourful of Flynn’s life – are painted with a broad and melodramatic brush.

Here’s our hero again, this time stumbling into a smoking, coastal village devastated by raiding mountain headhunters:

‘There were charred bodies, guts were strewn all over. Children lay around decapitated. All had their skulls cracked open: the normal custom, for the brains were taken away and eaten. The worst sight of all was where a half-dozen tall pointed stakes had been driven into the earth. Pregnant women had been impaled on these points: the baby on top of the stake, on the sharp point, and the mother’s body with the stake right through it. The flies were there in swarms working on the entrails.’

Nearby, hiding, he discovered a girl, ‘a honey-coloured girl of exceeding femininity…a perfect figure, and the most lovely little hollow, and then the line goes way up into the air and tattooed’.

What to do? Leave her? But then those headhunters might return. ‘I took another sharp look at her breasts and made the decision. “She comes with us.”’

Whatever the ‘stretch’ of this story, gruesome, erotic and humorous in turns, and whatever his co-writer’s part in it, one thing is certain: Errol lusted for young girls then and for the rest of his life. Later, on a Port Moresby tobacco plantation he owned, his ‘Boss Boy’ introduced Errol to his daughter. Once again he mentally gawped at ‘little up-pointing breasts so symmetrical and perfect as to have been attached by some means I didn’t stop to explain to myself…I had to buy her.’

Both girls were clearly very young. Flynn, unabashed, explained in My Wicked, Wicked Ways that ‘…there is no such thing as age in New Guinea. A girl generally matures about 12’. He cultivated a predilection for under-age sex in New Guinea and it stayed with him throughout his life. Under-age girls were the demons that lay in wait for Flynn. They brought him to the brink of disgrace and a long prison sentence and at the end he died in the arms of a 17-year-old.

The New Guinea years, as Flynn tells them, were a glorious cavalcade of lusty adventures in a Stone Age land. He tells of witnessing the hangings of New Guinea tribesmen for killing white men. He tells how he himself was charged with murder (A darker and deadlier variation of the yarn he retailed for the Melbourne Argus, this time it has one of his carriers fatally speared as Errol shoots a headhunter dead.) Flynn says he was acquitted when he was able to take the court to the ambush site where the body of his dead ‘boy’, skewered by a spear, still lay. He argued self-defence, and in any case there was no habeas corpus – the dead headhunter’s body had been taken away.

He tells of being fired as assistant District Officer and getting a job as an overseer in a copra plantation. He tells of buying a joint interest in a schooner, the Maski, and then working on another boat, the Matupi, with a gold prospector, Ed Bowen. As a sideline, he and Bowen hunted the PNG national emblem, the glorious Bird-of-Paradise, whose plumage was highly coveted in the thirties.

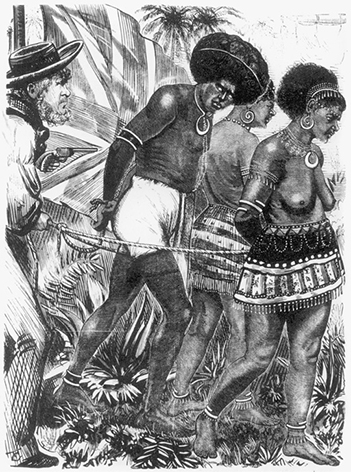

They also went in for ‘blackbirding’.

‘If you could get into the hinterland and bamboozle the natives into coming back with you to a plantation or a coastal city, you would be in the chips. They were strong fellows, good workers, and you could sell them to plantations or at ports for use in the goldfields. I was a little young perhaps to go in for slave trading, but it was an acknowledged way to turn a penny.

‘Recruiting was what they called this form of slave stealing and when you got a bunch of boys in your grasp they were called “indentured labourers.” It was one of the main businesses of the rough-and-readies like myself who flocked into the New Guinea Territory.’

‘Blackbirding’ was one of Errol Flynn’s shady occupations. ‘I was a little young perhaps to go in for slave trading, but it was an acknowledged way to turn a penny.

In New Guinea, in 1931, aside from the rough-and-readies – never mind the nubile smooth-and-readies – he met another, less attractive but charismatic figure, a man who was to play an important and intriguing role in the Flynn saga.

Dr Hermann Friedrich Erben was 36 when he met young Errol. A man after Errol’s own heart, he was a con man, a sexual predator, a pioneer in the exotic field of tropical medicine, an explorer, an adventurer and a soldier of fortune. He was also a Nazi spy. Dr Erben hired Flynn and his schooner to sail up the dark and dangerously unhealthy Sepik River to find and film headhunters. Flynn readily agreed and they sailed on Flynn’s schooner. (Flynn came out of New Guinea with malaria, an illness that, combined with a weak heart, stopped him from serving in the US military. He tried to volunteer, said his friend David Niven, but was classified 4-F: ‘unfit for military duty’.)

Erben played a powerful role in Errol Flynn’s life. Together, after New Guinea, they roared through the Philippines, China, Vietnam and India. In all these exotic locations they distinguished themselves. In brothels and bars, in scams and scandals, in sickness and in health (in Shanghai Flynn contracted what he called the Pearl of Great Price – gonorrhea) they demonstrated an unerring capacity to find themselves in and out of trouble but always one jump ahead of retribution and the people they swindled.

(Years later, when New Guinea debtors – there were many – wrote asking the now wealthy star for payment he would send them an autographed photograph of himself with a form letter explaining to the slower-witted that in years to come it would be worth considerably more than their puny outstanding invoice.)

Finally, in Marseilles in 1932, they parted: Erben to return to his native city, Vienna, where the Nazis were now a powerful force, and Flynn to England in search of fame and fortune. (They next met when Flynn had both – in 1937, in Paris. Erben persuaded Flynn, now the hottest movie star in the world, to go with him to Spain where, in the flimsy guise of a war correspondent, Flynn was, briefly, a spectator at the Civil War.)

Flynn never lost his adolescent veneration for the sinister Dr Erben. In 1980 Charles Higham wrote a book claiming that Erben recruited Flynn as a Nazi spy. Norah Eddington, Flynn’s second wife was infuriated by the claim.

‘Errol was a wild spirit and about as unconventional as any man ever born,’ she wrote in a letter to the Los Angeles Times. ‘He hated authority, particularly policemen, and so the idea of him being attracted to the Nazis is absurd…I would also like people to know that Sir William Stevenson, who was the Chief of British Intelligence, has said that Errol was not a German spy.’

The book’s flavour and accuracy can be gauged from this excerpt:

‘He and Erben had much in common. Errol inherited his anti-semitism from his mother, but she was not alone in hating Jews. Tasmania was as racist as Austria…in Hobart, Jews were tortured at school, eliminated from businesses if found out. They were forbidden to work in politics or the police department, and their shops and offices were smashed by hoodlums. There were strange, militaristic clubs whose members donned uniforms and jackboots – almost like Nazis themselves…filled with disgruntled Irish expatriates, the country, male-dominated, chauvinist, worshipping the male body, had an under-current of sadomasochistic repressed homosexuality to which Errol responded.’

And that was only on St Patrick’s Day!

Still, Dr Hermann Erben undoubtedly exerted an influence on Flynn beyond that of any other man or woman. Here’s Flynn’s vivid description of him, on a boat taking them to India.

‘Each morning he stood naked at the ship’s stern, absorbing the sunshine – head thrown back, a vast Epstein-like sculpture, grossly misshapen, baring his gleaming teeth fang-like to the sun. He had a theory that sunlight was good for the gums and throat. He stood with his hairy blond legs, thighs stretched wide apart. His huge flabby belly undulated uneasily with each breath. His entire torso was covered with dense blonde hair. He was a heroic sight – except for the incongruously small phallic symbol between his legs.’

Erben’s phallic symbol may have been small, but as things turned out within a few years Flynn was to complain bitterly, and for the remainder of his life, that he was seen as nothing more than ‘a 6ft. 2in., walking phallic symbol’.

‘What,’ the District Attorney asked pretty Peggy Satterlee, ‘was the next thing that happened?’

‘Mr Flynn came into the room.’

‘How was he dressed?’

‘He had on pyjamas.’

‘What was said?’

‘I asked him what he wanted and he just said he wanted to talk to me. I asked what he was doing in a lady’s bedroom…he asked if he could get in bed. He said he would not hurt me, but would just get in bed with me. He got into bed with me and completed an act of sexual intercourse.’

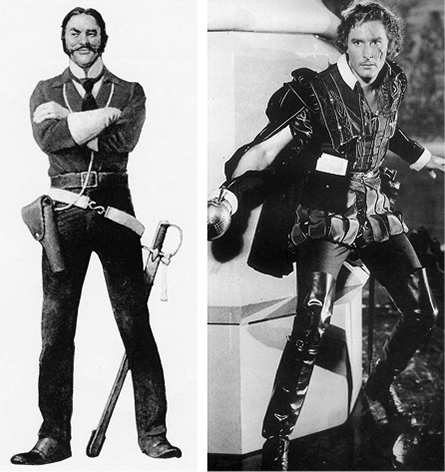

On 11 January 1943, in the Los Angeles Hall of Justice, Errol Flynn’s life went into the first phase of what was to become a tragic decline. He was at the peak of his career. Eleven years before he had been spotted on a Bondi beach and cast in the role of Fletcher Christian in the Australian producer/director Charles Chauvel’s movie, In the Wake of the Bounty. Two years later he tried his hand at acting again, this time in England where he had bluffed his way into an acting job with Northampton Repertory Theatre before making his mark in a third-rate thriller called Murder in Monte Carlo, a dismal British movie that nonetheless came to the notice of Jack Warner, who invited him to come to Warner Bros’ California studio for screen tests. Flynn took the next boat.

On board the Paris, he met his first wife, the woman he was to call ‘Tiger Lil’ – a gorgeous and fiery French movie star, Lila Damita, returning to Hollywood to co-star in a movie with Jimmy Cagney. There seemed to be little ahead – in the work sense – for her young bunk mate, the unknown Errol Flynn, but neither of them was concerned about his career at that stage.

Catch a tiger

Lila Damita and Errol Flynn were made for each other – intoxicated with passion, at least for the little time it took them to meet and get married. But Flynn was not made for marriage. ‘Tiger Lil’, David Niven recalled in his autobiography, Bring on the Empty Horses, ‘taught him a great deal about living and living it up, but a quick marriage in Arizona in 1935 did nothing to dispel her pathological possessiveness and in the next few months during a spate of Herculean battles, Flynn drifted away from her’.

Inevitably Flynn went to his playmate Niven and suggested they set up in a bachelor pad. ‘Let’s move in together, sport, I can’t take that dame’s self-centred stupidity another day.’

The marriage may have been a quickie, and Flynn may have abandoned it soon after, but it took seven years of on-and-off relationships, numberless affairs and tempestuous knock-down-

drag-out fights before they called it quits. They divorced in 1942. Damita won a tax-free alimony of $1500 a month plus a half interest in all his properties. In turn, in 1941, she gave him Sean, who inherited his father’s looks but grew up loathing him. A photojournalist, Sean disappeared in Cambodia during the Vietnam war.

Then, in 1935, he got a dream break. Lounging around Hollywood, playing a lot of tennis, and playing up a whole lot more, he was unexpectedly thrust into the starring role designated for Robert Donat in Warner Brothers’ pirate epic, Captain Blood.

He was an instant sensation. The world was dazzled by this new, improved, extra strength Hollywood leading man. Errol Flynn was 26 and radiated with a pure beauty seldom seen in men: laughing eyes, dazzling teeth, square jaw, broad shoulders, a slim but muscular 6 foot 2, and the whole informed by a zest and agile grace that was entirely unique. Above all Flynn had tremendous sex appeal.

Flynn got $1500 a week for Captain Blood and followed that landmark movie with The Prince and the Pauper and then an even bigger success, playing opposite Olivia de Havilland in the Technicolor classic, The Adventures of Robin Hood. The next year, 1939, another smash, The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex, with Bette Davis and the two having legendary off-camera battles. (Flynn was a noted boxer, bested by very few men, but Bette is said to have knocked him cold in one of their tiffs.) In 1940 came The Sea Hawk and then the roles of General Custer in They Died With Their Boots On and the heavyweight champion Jim Corbett in Gentleman Jim.

By January 1943 Errol Flynn was one of the Hollywood elite, the subject of international adoration, envy and endless salacious gossip. Unlike his movie peers – Clarke Gable, Humphrey Bogart, Gary Cooper, John Wayne and Cary Grant – Flynn’s screen image and his private life were virtually identical. He was the same reckless, dashing, devilishly handsome hell raiser on screen and off. His love life was now legendary. It was accepted that he could have any and all the women he wanted.

So why did he want Betsy?

Betsy Hansen was a 17-year-old drugstore waitress, a girl Flynn described as he was being arrested as ‘a frowsy little blonde’, adding bitterly, and incriminatingly, ‘I hardly touched her!’ There is no denying that Betsy was a rather plain bubblehead, a girl with an overbite and a pasty complexion: a million miles from the woman Flynn was then living with, the dark beauty, Linda Christian.

On 27 September 1942, however, Betsy and some friends from Warner Bros. studio gate-crashed a lively Bel-Air party where, she said, Flynn, who had been playing tennis, chatted with her, sat her on his lap and, when she had drunk too much, took her upstairs and raped her.

Betsy didn’t bother to report the incident and it came to light only when she was picked up by the police in a seedy hotel and Flynn’s telephone number was found in her address book. Betsy told them Flynn had sex with her twice. Asked if she had resisted Flynn’s advances Betsy said, ‘No, why should I?’

A few days later another teenager, Peggy Satterlee, claimed that Flynn had twice made love to her on his yacht, the Sirocco.

Flynn held Peggy Satterlee, 17, a dancer, in high regard. A stunning and charming brunette, she had caught the eye of the movie idol as an extra on the set of his recent movie, They Died With Their Boots On. Later, at a nightclub, her sister introduced her to Flynn. Peggy Satterlee, he said, ‘had sensational upholstery’.

To defend Flynn against charges of statutory rape (sex with an under-age girl) Warner Bros. hired the most famous trial lawyer in America, Jerry Geisler, a master of the honey trap technique of cross-examination. The two 17-year-olds were no match for him.

Both gave testimony that, if true, revealed the screen Casanova to have the seduction techniques of a schoolboy. Betsy told the court that once Flynn took her upstairs to lie down after drinking at the Bel-Air party she had allowed Flynn to undress her, saying as he did so, ‘You don’t think I would really let you go downstairs do you?’

She had said, ‘Yes, I do.’

‘So, he removed all your clothing?’

‘Yes sir. Everything except my shoes.’

‘What clothing did he remove?’

Betsy was blunt.

‘He removed everything but his shoes.’ The court erupted. (They Died With Their Boots On was playing in hundreds of movie houses across the country.)

Peggy Satterlee, for her part, said Flynn left his socks on when he forced himself on her, causing one wag to suggest that the title of Flynn’s forthcoming movie Gentleman Jim should be retitled Jim.

Geisler got Betsy to admit that she had given oral sex to her boyfriend (then an offence) and had sex with two young men who had gone to the Bel-Air party with her. And Peggy, who appeared in court in pigtails, flat shoes and a young girl’s dress was forced to agree that she and her sister lived in an apartment paid for by a pilot and that she had once pranced around a mortuary with the pilot and – shades of Abu Ghraib – pressed their faces against those of the corpses. She’d also had an illegal abortion.

Most damning, because it was melodramatically shown to be false, was Peggy’s testimony that Flynn had lured her below deck where together they had looked at the moon through a porthole of the Sirocco. Geisler demonstrated that the moon was showing on the other side of the moored yacht on that night. The jury – two men and nine women, came back with a not guilty verdict on both counts but Betsy and Peggy had done for Errol Flynn. He was never the same man.

‘In those days Errol was a strange mixture,’ David Niven wrote in Bring on the Empty Horses. ‘A great athlete of immense charm and evident physical beauty, he stood, legs apart, arms folded defiantly and crowing lustily across the Hollywood dung heap, but he suffered, I think, from a deep inferiority complex; he also bit his nails. Women loved him passionately, but he treated them like toys to be discarded without warning for a new model, while for his men friends he preferred those who would give him least competition in any department.’

This innate insecurity, undoubtedly born of his mother’s rejection of him, and the lonely life he led for much of his youth, had been concealed all his life under the cavalier swagger and charm that had swept all before him. Now he was shamed, humiliated, in the eyes of the world. Errol Flynn was a laughing stock, a walking phallus. (The Hollywood grapevine had it that Flynn was a man of ordinary sexuality, haunted and mocked by his reputation as a prodigious lover.)

During the trial a journalist had coined the phrase ‘In like Flynn’. It stuck and he hated it. Despite his incorrigible bent he had always craved respect and now, he knew, he was never to get it. (There was another half-baked rape and indecent assault charge in Monaco in 1951.)

Exacerbating his humiliation was the universal ridicule and contempt for his role in Operation Burma, a war film that was perceived to show Errol Flynn – who had starred in the movie while missing war service – single-handedly defeating the all conquering Japanese in Burma. This was a surprise to the 180,000 troops of the 14th Army who had been in Burma and who had no recollection of running across him during the campaign.

In the post-war years as his star began to fade Flynn increasingly took refuge in morphine, cocaine and vodka. His face coarsened, his once slim body thickened. During the trial he had met a striking redhead, Norah Eddington, the 18-year-old daughter of the sheriff of LA County, who served behind the cigar counter at the Hall of Justice. Each day Flynn flashed his dazzling smile as he passed the cigar counter on his way to more humiliation. They married in 1943 but divorced five years later and Flynn quickly remarried. This time his bride was another film star, Patrice Wymore. Unlike ‘Tiger Lil’ Damita, both women remained fond of the old rascal to the end.

The Adventures of Don Juan, made in 1948, a tongue-in-cheek reminder of Flynn’s golden years, was his last major film and for the next 10 years he was, in effect, committing suicide – painstakingly slowly.

His movie roles got smaller and fewer. In 1957, he won the critics’ applause playing a character very similar to himself: a boozy burnt out case, in the film adaptation of Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises. It was the sort of dramatic performance he had always felt himself capable of, but time was running out for him to reinvent the character that he had crafted so carelessly over almost five decades.

In 1958 he met Beverley Aadland. A Las Vegas dancer at the Sahara from the age of 13, Beverley, 16, was the daughter of a one-legged former dancer. Beverley had been around the block quite a few times, but her mother Flo always insisted – a waste of breath surely – ‘My baby was a virgin the day she met Errol Flynn!’ (Flo may have had mixed feelings about Flynn. She once complained that in wintry Times Square Errol had sent her hobbling from a cosy movie house where the three of them were enjoying a film, to hunt down a bottle of vodka.)

By that time, said Norah Eddington, who met him in New York with their two daughters, Flynn ‘looked like a man with one foot in the grave’. On the brink of bursting into tears she ‘just wanted to take him in my arms, to baby him, to take care of him. He had aged: he was enormously heavy; the weighty hand of dissipation was on his once beautiful features’.

On 9 October 1959, Flynn and Beverley Aadland flew to Vancouver, where Flynn was hoping to sell his yacht to a Canadian millionaire, George Caldough. On the way to the airport Flynn fell ill and Caldough stopped at the apartment of a friend, a doctor, who advised that Flynn should lie down in his bedroom.

When Beverley looked in, 30 minutes later, Flynn’s face had turned blue and his lips were trembling. He died in her arms trying to speak.

What was he trying to say?

It’s tempting to think his last words would have been along the lines of a Christmas message he broadcast to Australia and that concluded:

‘If there’s anyone listening to whom I owe money, I’m prepared to forget about it if you are.’

How he got the part. Takes 1,2,3,4

In 1931, Flynn returned to Sydney from New Guinea. Borrowing £300 from his mother, he bought an old yawl, Sirocco, and with four mates made a leisurely return trip up the Queensland coast, through the Great Barrier Reef, and on to Port Moresby where he managed a tobacco plantation. When he returned to Sydney the following year he found himself in the role of Fletcher Christian in Charles Chauvel’s In The Wake of the Bounty, the Australian movie based on the mutiny on the Bounty.

Like almost everything in Errol Flynn’s life there are a number of versions of how Chauvel discovered his star. It is said he was struck by a newspaper photograph of Errol, with a caption telling of how the young Australian had swum ashore from a shipwreck off New Guinea. Chauvel’s wife Elsa is sometimes credited with seeing Flynn in a Sydney pub (a ring of truth here) and the movie’s casting director may have spotted Errol sunbaking on Bondi beach. Another, more elaborate, amusing and implausible story has Flynn impersonating the chosen actor who Elsa Chauvel had seen only on stage.

Elsa saw the man, John Hampden, perform in Melbourne and went backstage to invite him to come to Sydney the following weekend to sign the contract. Flynn arranged for Hamden to be met at the station and tricked into going to a non-existent meeting. Meanwhile Flynn arrived at Elsa Chauvel’s office.

‘Who are you?’ she asked and, falling on one knee, in a pose from the period play Hampden was starring in, Flynn replied, ‘It’s me, Hampden.’

‘You look so different without your make-up!’ Elsa said and then, when he signed ‘Errol Flynn’ to the contact, ‘But you are John Hampden!’

‘Just my stage name.’

Could it possibly be true?

Flynn himself said: ‘However, despite good reviews (with the exception of the Bulletin) the film was overshadowed when Hollywood released its own version, Mutiny on the Bounty, with the world’s biggest star, Clark Gable in the role of Fletcher Christian.’

Flynn and Flashie – spot the difference

The parallels between Errol Flynn and the fictional character Flashman can be seen in these two excerpts, one from Flynn’s autobiography, My Wicked, Wicked Ways and the other from Flashman on the March. The two are interchangeable.

‘Madge [in Sydney and broke, he had been picked up by a rich, older woman] was my first experience of what a real woman could mean. But there was no future for me in Madge either, and I am quite sure she knew it too.

At that moment my eyes lit on the dressing-room table. There, sparkling at me, were a few jewels, big ones, small ones. Some had gold or silver chains, and there were a couple of rings.

I looked back at the bed where she lay, a lovely picture, arms outspread, lovely full breasts.

This is criminal. Not the way to treat anybody. She has been so wonderful.’

He scooped up the jewels.

From My Wicked, Wicked Ways

‘…in another moment both of us would be swept away into that thunderous white death in the mist. There was only one thing to be done, so I did it, drawing up my free leg and driving my foot down with all my force at Uliba’s face, staring up at me open mouthed…one glimpse I had of the white water foaming over those long beautiful legs, and then she was gone. Damnable altogether, cruel waste of good womanhood, but what would you do?’

Illustration and excerpt from Flashman on the March

In 1958 David Niven bumped into Flynn in London. Niven, who hadn’t seen Flynn since the glory days, was shocked by his friend’s disintegration. The once beautiful face was puffy and blotched, but there was an internal calm and compassion that had never been there during their roaring years. The pair went for a long lunch in a French restaurant in Soho.

Over the brandy and cigars Flynn told Niven, ‘I’ve discovered a great book and I read it all the time – it’s full of good stuff.’ Then he warned, ‘If I tell you what it is sport, I’ll knock your goddamn teeth down your throat if you laugh.’

Niven promised to keep a straight face.

‘It’s the Bible,’ Flynn said.

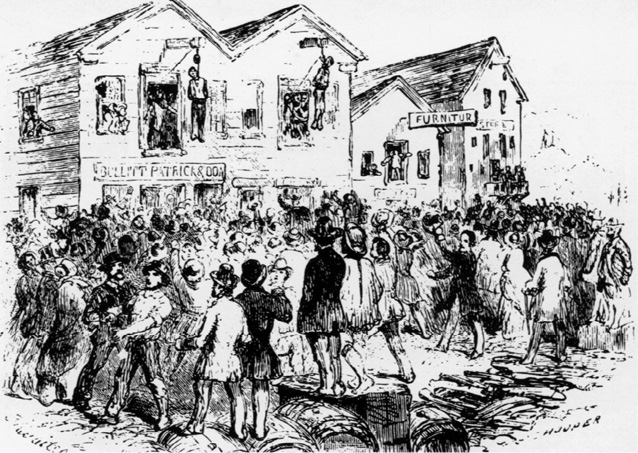

Our star turns at the Vigilantes’ necktie party

John Jenkins didn’t imagine for one moment that he was going to a necktie party. Jenkins was quietly going about his business – stealing safes – when he was seen by a passer-by. The man went hotfooting down the waterfront hollering for the Vigilantes. Jenkins had been manhandling the safe in the street at Long Wharf and he was cool enough – and greedy enough, there was $1500 inside its steel walls – to carry on and bundle it into his boat. He was leaving the scene of the crime just as the Vigilantes came galloping up.

Jenkins heard the horses thundering into Long Wharf before he saw the Vigilante posse and heaved the safe over the side. His heart sank with the safe: it lay there for all to see, sticking up in only a few feet of water.

At 10 p.m. Jenkins was bundled into the Vigilante committee rooms in Battery Street and his trial began. By midnight a bell rang summoning the citizens of San Francisco to a lynching.

Until he heard the bell Jenkins had affected a nonchalance born from his experience that the Sydney Ducks, again and again, could flout the law and escape without punishment in the Wild West town. If the worst came to the worst he’d be sprung from jail; or the snivelling, craven townsfolk, frightened of reprisals, would not dare pass sentence of death on him. Most likely he’d be run out of town and he’d come back in his own sweet time, meet up with the Ducks – Gentleman Jim, Singing Billy, Jack the Dandy and the rest of the boys, and it would be business as usual.

‘Do you have anything to say?’ the head of the jury asked him. Jenkins was a bully and a loudmouth but he wasted few words on them.

‘I have nothing to say. I only wish to have a cigar.’

They gave him the cigar and told him that he would swing by morning.

Morning? Already some, like the Vigilantes leader Sam Brennan, felt there had been far too much palaver. Brennan’s views on the Sydney Ducks and the best way to show them the error of their ways had appeared in black and white in his newspaper, the California Star.

‘Where the guilt of the criminal is clear and unquestionable, the first law of nature demands that they be instantly shot, hung or buried alive,’ he’d thundered.

Jenkins was clearly and unquestionably guilty and now he had to ‘rise with the sun’ – sooner if Captain Howard, impatient and getting to the nub of the matter – had his way. ‘I thought we came here to hang somebody!’ the captain said.

Sam Brennan sent a man out for a rope and another to fetch a parson. The Reverend Flavel Mines hurried in and spent 45 minutes in private with Jenkins preparing him to meet his maker until a Vigilante, exasperated at the delay, burst in:

‘Mr Mines, you have taken about three-quarters of an hour, and I want you to bring this prayer business to a close. I am going to hang this man in half an hour!’

At 2 a.m., they dragged Jenkins, his hands tied behind him, outside and down the street while a couple of thousand ruffians, who had gathered to enjoy the spectacle of an impromptu floorless jig, jeered and cheered.

They slung the rope first over a flagpole. But the crowd, outraged, saw this as unpatriotic and Jenkins was hauled to the old Spanish Adobe. There, at the corner of the town square, they threw the rope over a beam, slipped a noose over Jenkins’ head and about 20 men hauled him high. Legs kicking wildly, his body twisting in agony and desperation, he strangled. Now all the Vigilantes had to do was to string up the rest of the Sydney Ducks.

There was Palmer the Bird Stuffer; The Slasher; Wilson the Horse Thief; Bluey; Long Charlie; Little Charlie; there was James Stuart, known variously as ‘English Jim’ or Gentleman Jim,’ a forger, gold robber, arsonist and murderer; Sam Whittaker, a man you didn’t turn your back on; Singing Billy, Thomas Belcher Kay, a corrupt official; George Adams, ‘Jack the Dandy’, whose specialty was cutting duplicate keys, and a few score more vicious criminals – Sydney Ducks – who had come to seek their fortune in the wild gold rush town that was San Francisco in 1851.

The California gold rush began in 1848 when a carpenter discovered the yellow metal in Sierra Nevada. Just as it did in Melbourne, three years later, the magic of the word gold transformed San Francisco within weeks. In Australia, in the Old Barracks in Sydney, shipping agents mounted posters screaming ‘Gold! Gold! Gold! In California’ and the Sydney Morning Herald authenticated this with stories that prospectors could collect up to $1500 worth of gold in a week – a year’s wages for the entire reporting room of the Herald.

‘There are no poor men in California,’ the Herald breathlessly asserted. ‘The most indolent man can easily procure his ounce or two per diem and hundreds daily obtain two or three times that amount.’

Reports like that had thousands of Sydney men catching the first boat to San Francisco, and among them were those most indolent of men – criminals, ex-convicts mostly, who had served their time, and who knew that where there was gold there were easy pickings to be had.

In San Francisco, skulking in the quarter called Sydney-town, they were to become known as the Sydney Ducks – Americans, disparagingly said the Australian accent had a quack-like sound to their ears.

Once off the ship in San Francisco the soon-to-be Sydney Ducks went straight to Sydney-town. On the slope of Telegraph Hill, among the lowlife bars, the hovels and the whorehouses, they settled into a life of crime that allowed them far more liberty and far greater rewards than they had enjoyed back in Australia.

San Francisco was a town where gun law ruled. There were around 75 policemen to keep order among 20,000 mostly wild men. A hundred thousand gold seekers from around the world – wide-eyed optimists hoping to pick up a bag of nuggets and sail back to Sydney to retire; desperate, disappointed down-on-their-luck men; card sharps and confidence tricksters; bully boys and gunmen; men of God and gullible men and a few thousand women – mostly prostitutes – passed through San Francisco on their way to the Sierras between 1848 and 1851 and what law there was had no chance of keeping order.

‘Horse stealing is common…murders everyday occurrences, and everybody carries…pistols for self defence,’ said the Sydney Morning Herald, now singing a different tune.

On San Francisco’s waterfront and at Sydney-town taverns, in The Noggin of Ale, the Jilly Waterman, the Port Phillip House, and in the Magpie, the Sydney Ducks plotted garrottings, forgeries, highway robberies, bank stick-ups and murders.

Some of the publicans themselves, old lags from Sydney, were known to be receivers of stolen property. And if any of the gang were caught, well, the Ducks were expert, too, at fixing trials, faking alibis, introducing fraudulent witnesses, corrupting court officials and intimidating witnesses.

There was no question that they were beyond the law. The question was what could be done about it?

The California Courier took it upon itself to supply the answer. The Sydney Ducks ‘brought the city to a crisis where the fate of life and property are in immediate jeopardy,’ it editorialised. ‘There is no alternative now but to lay aside business and direct our whole energies as a people to seek out the abodes of these villains and execute summary vengeance upon them.’

That was the feeling, too, of the Courier’s readers. Leaflets went out reading:

Citizens of San Francisco, the series of murders and violence that have been committed in this city, without the least redress from the laws, seems to leave us entirely in a state of anarchy…redress can be had for aggression through the never failing remedy so admirably laid down in the code of Judge Lynch.

Judge Lynch was soon to be called upon.

In 1851, a storekeeper, Jansen, bent over his account books late one night was set upon, robbed and bashed almost to death. Marshall Fallon, San Francisco’s chief law officer, arrested two men, Berdue and Windred, in the mistaken belief that they were ‘Gentleman Jim’ Stuart and his accomplice. The storekeeper was in a bad way and he could not positively identify the two – but he recognised the quack of their accent. They were Australians, it was true, and one of them, Windred, was a Sydney Duck. But they were both innocent. Fallon’s hunch that the robbery was the work of Gentleman Jim and his partner was correct.

The two men’s trial began at City Hall but by nightfall, with proceedings adjourned until the morning, there was a crowd of several thousand outside shouting for action, ‘Bring ’em out! Lynch ’em! String ’em up!’

The following day the jury was wrestling with entirely reasonable doubts about the guilt of Berdue and Windred. This indecision enraged the lynch mob outside. They kicked in windows, crashed through doors and stormed the building. As the jury, with six shooters in hand, held off the insurgents, Berdue and Windred were hurriedly bundled out the back and taken to a safe place. Two weeks later they were found guilty as charged, of assault and robbery, and sentenced to long terms of imprisonment: 14 years for Berdue and 10 for Windred.

The Sydney Ducks were accustomed to springing men from jail. They did it again for Windred, using a duplicate key that Jack the Dandy had cut, and on 5 May 1851 Windred and his wife were smuggled aboard a ship for Sydney. Berdue they left in jail.

It was the last straw. Sam Brennan, a Mormon who was editor of the California Star, and a man with a not unblemished record himself, was all for forming the Vigilantes and getting to work on ridding San Francisco of the Ducks. A rival newspaper, the Alta California, weighed in with much the same idea: ‘I propose then to establish a committee of safety whose business it shall be to board every vessel coming in from Sydney, and inform the passengers that they will not be allowed to land unless they can satisfy this committee that they are respectable and honest men, and let anyone transgressing this order be shot down without mercy.’

On 9 June 1851, the townspeople elected a Vigilante committee with Brennan at its head.

He got his chance the next night. And by the early hours of the following morning the Vigilantes were looking up at the Cuban-heeled boot soles of John Jenkins, the late Sydney Duck.

The next month they caught Gentleman Jim.

James Stuart, English Jim, Gentleman Jim, was an exceptional man who, as a 16-year-old had been transported to Australia for forgery and who now had established a formidable record in San Francisco as a villain who could be relied upon to do anything. He led a gang of highwaymen, he had a horse-stealing ring, and he robbed gold transports.

In Monterey he had the nerve to appear in court under an alias and give false evidence to swing a hung jury, and, while the jury deliberated on his fresh evidence, helped the accused escape custody. In 1850 he was imprisoned for his role in the theft of gold bars worth $5000. The jail couldn’t hold him and he escaped to Maryville where he shot and killed a man, Charles Moore, and then had to flee back to the safety of Sydney-town when Moore’s friends came looking for him.

An ice-cold killer, good-looking and ruthless, James Stuart’s time was up a month after they got John Jenkins. He was unlucky. On 4 July, Independence Day, the Vigilantes picked him up in a round-up meant to catch a burglar. He passed himself off as a William Stephens, and was about to walk free when one of the Vigilantes recognised him: ‘Hello, Jim. What are you doing here?’ It was all up for Gentleman Jim. He did his best: he turned over more than 100 of his Sydney Duck mates – named them all and told them of his life as a thief and an arsonist. It was very helpful, but Gentleman Jim was always going to swing.

Australian badmen Sam Whittaker and Bob McKenzie left their hearts – and everything else – in San Francisco when Vigilantes slipped nooses over their necks and flung them from windows - Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

The Committee of Vigilance considered all this, took a vote and ‘Resolved: That prisoner Stuart be hung – unanimously carried.’

They took Gentlemen Jim down to the pier at the foot of Market Street and flung a rope over a derrick while a large crowd cheered. The Mayor, Charles Brenham and Judge Myron Norton rode up and appealed for a return to law and order.

Sam Brennan had an answer to that. ‘We are the Mayor and the Recorder. The hangman and the laws! The law and the courts never yet hung a man in California,’ and Brennan and his Vigilantes were about to rectify that. Stuart dangled at 3 p.m., but not before he had cleared the guiltless and still imprisoned Berdue.

A few weeks later, on 24 August, two of the Ducks Stuart had implicated in his crimes, Sam Whittaker and Bob McKenzie, were arrested and waiting for trial when a party of Vigilantes broke down the jail door and brushed past the guards. Sheriff Hayes was away that Saturday afternoon, at the bullfight.

The Vigilantes marched the struggling pair to their Battery Street committee rooms and, only seventeen minutes after they were taken from their cells, McKenzie and Whittaker, tightened nooses around their neck, were taken to the second floor where a double gallows had been rigged, and flung out the windows.

Sydney-town was deserted within days. That same month gold was discovered in Ballarat and the Sydney Ducks disappeared into history.

The Boys’ Own adventures of the most influential Australian who ever lived

‘Are you up for the Fu?’ It was Strouts and raining. He had a cup of tea at the Customs mess while I slipped on my things, and I went over with him. We crossed by the deep cutting and stone barricade to the south of the Legation and in the Fu kept well under the wall while making our way to the outpost. The wall was pitted with shot and shell. It was difficult to image how I could have passed it unhurt yesterday amid that hail of bullets.

It was 16 July 1900. The writer of the above, George Ernest Morrison, was now ‘Chinese’ Morrison, and about to become ‘Morrison of Peking’. He was also about to be shot. Strouts, too. But Strouts would be shot dead. Morrison and Captain B.M. Strouts were on their way to the crowded, chaotic ‘Fu’, the compound where 3000 Christian Chinese had fled from the Boxers – fanatics who were hunting them down, house by house, to be slaughtered.

For a month they, and the 800 Europeans and Japanese in the embassy compound inside the imperial capital of Peking, had been under siege by the Boxers, supported by the Chinese army, and with the full blessing of the decadent and treacherous Empress of China. The situation was desperate. There was no hope of help arriving within the next month or more. Morrison must have been loving every minute of it.

An audacious, fearless adventurer who was carried from an ambush in New Guinea with spearheads deep in his head and stomach; a journalist – unquestionably Australia’s greatest; a secret agent; a man who saved the lives of hundreds and emerged the hero from the tumultuous and bloody 55-day siege of Peking; a political strategist who helped bring down the last Chinese Emperor and became the close adviser to the president of the new Chinese republic; a pivotal figure in Japan’s historic attack on Russia, George Ernest Morrison has been called the most influential Australian who ever lived. In Hong Kong ‘Banjo’ Paterson bumped into him and wrote that of the three great men of affairs that he had met up to that time – Morrison, Cecil Rhodes, the father of Rhodesia, and Winston Churchill, ‘Morrison had perhaps the best record…he outclassed the smartest political agents of the world.’

He was a legend in his own time. But his own time was too long ago for most of us.

Now, eight decades after he died, after clinically noting his imminent demise in his diary: ‘Almost can believe death struggle began’ – George Ernest Morrison is almost entirely forgotten in his native country.

I loafed about the town for an hour or two and in the afternoon went down to the Oval to see Jarvis play [cricket].

As I seated myself in the grandstand a general titter passed through the crowd and everybody tried to be funny at my expense. Just because I had on a flannel cricketing shirt – perhaps a little dirty – old serge breeches, a green cap, leggings, old boots and a knapsack.

One pertinacious old fool was very inquisitive and would have it that I had been down two years before with sheep and he had seen me.

I have now finished my walk and my diary and I certainly have found the latter the more arduous of the two. I am now fairly done up with exhaustion so I’ll shut up.

By the way, Jarvis got run out first ball.

Young George Morrison, as he says in this extract from his diary of 14 February 1880, had just finished his walk. What he doesn’t say is that he’d walked 600 miles, from Geelong College, where his father was the headmaster, to Adelaide ‘to while away my holidays’.

He had turned 18 just 10 days before, but already the clues to his character can be found in the pages of the diary. He is a sports lover, (a passionate follower of the Geelong Australian Football team). He is bashful around women. (In the Botanic Gardens, ‘by the strangest coincidence in the world I met sweet Annie Evans,’ but, unexpectedly, his father encounters them. ‘I feel I am blushing up to my eyelids.’). He is attracted by danger: ‘The whole country is in a state of alarm at the Kellys, the dead body of a constable has been found riddled with bullets.’ He has a cutting but amusing wit. ‘This elderly gal…has got a squeaky miserable sort of voice, just such a voice as you would expect from a woman of 38 who has a bust like a deal board, a set of teeth bought in Colac (and second hand even then) and a mouth graced with a moustache a la Lord Harris.’ And he is intrigued by journalism: ‘[Forbes] for his newspaper corresponding service in the Turko-Russian war was allowed £5000 expenses and when he got home received 2000 from the proprietors of the Daily News.’

Encouraged by his mother, to whom he was devoted all his life, he offered the Melbourne Age publication rights to his account of his walk to Adelaide and it was published in the Leader, the Age’s weekly magazine, as The Diary of a Tramp. He was paid seven guineas. Small beer for Forbes perhaps, but a start.

With it he bought a canoe and prepared to paddle almost 1200 miles down the Murray, from Wodonga to the sea. He would be the first to do so. He named the canoe Stanley, in honour of his hero, Sir Henry Stanley, ‘Special Correspondent to the New York Herald, the discoverer of Livingstone, the identifier of the Lualuba and Congo [Rivers], the greatest traveller of this or any age, the most extraordinary man, and the man for whom before all others in this world I admire most.’ (In London 19 years on, and then himself famous, he was to meet Stanley.)

Young George Morrison doesn’t say so, but clearly he dreamed of emulating his hero and making his name as an adventurer-explorer, the Special Correspondent for a great newspaper. The canoe expedition was part of his apprenticeship.

Once again the Age serialised his account, Down the Murray in a Canoe, and now David Syme, the proprietor of the trailblazing paper gave the teenager an extraordinary assignment. He wanted Morrison to expose the trade in ‘black pearls’ – the South Pacific islanders, men, women and boys whom ‘blackbirders’ lured or forced on to their ships and sold to Queensland sugar farmers. They did the exhausting, dirty work, clearing fields and cutting cane for a miserly wage before they were allowed home at the end of a specified period. The Queensland premier was just one of a number of influential figures profiting from the trade in human lives.

Morrison got a job as an ordinary seaman on a blackbirder, the Lavinia, taking 88 Kanakas back to their homes, ‘bright, clean, strong intelligent fellows whose labour surely is cheap at £18 for three years’. Returning the natives could be a risky business. Though many went willingly to Queensland, others were seized and taken aboard ship to the feared nickel mines of French Noumea. Cannibalism was popular among the islanders and blackbirders notorious for the way they treated their human cargo needed to take great care not to fall into their hands. Some did.

Morrison’s reports jolted Australia into a realisation that the trade had to stop, and the Age’s campaign played a powerful role in ending it. Morrison had made his name.

Next he decided to walk the length of the continent. Burke and Wills had attempted and failed the same trek only 21 years earlier, despite setting off with an expedition of 15 men, 21 tons of baggage and 54 camels and horses. Morrison, alone and with only a pack on his back, walked the 2,000 miles from the Gulf of Carpentaria to Melbourne in 124 days to the astonishment of the nation. The Age once again published his account of the walk and then commissioned him to take another walk – leading an expedition across New Guinea.

The New Guinea assignment – he was given the grandiose title of Special Commissioner by the Age – was exactly what he wanted. Tall, fair-haired and blue-eyed, 20-year-old George Morrison saw himself now, as he had a right to, as an explorer/journalist, an expedition leader in the mould of Stanley, venturing into a savage, unknown country.

David Syme, notoriously careful with his pennies, had such faith in the young man that he gave him, at first, an open cheque book to mount an expedition that came to rival that of Burke and Wills in size and in its tragi-comedic elements. The men Morrison chose to accompany him were a mixed and mostly comical lot. There were five white men, among them John Lyons, ‘by repute one of the best bushmen in the north’, and Ned Snow, ‘remarkably short and of such eccentric confirmation that, whereas his body seemed longer than his legs, his head appeared more lengthy than either’. There was a Malay named Cheerful – possibly because he was an opium smoker – and another, Lively, who was ‘curious’. All told, 25 men and boys and three native women set out from Port Moresby on 11 July, 1883 to cross the mysterious island. At the same time a rival expedition from the Argus also set out.

After 37 days on the track tribesmen attacked Morrison’s party and escaped with all they could carry away. Morrison shot one of them. Lyons wrote later, ‘He came and told us what he had done and said he felt like a murderer. That afternoon there was a great howling and crying among the savages.’ The next morning the expedition encountered a blunt warning on the track: crossed spears and a shield. Lyons argued for them to turn back. Morrison, of course, pressed on.

It was the wrong decision. Lyons heard rather than saw what happened next. ‘…a most piercing scream after which a shot was fired’, and discovered Morrison ‘stretched on his back and covered with blood from head to foot’. He had two spears in his body: one, driven into his head near his right eye, the other deep in his stomach. Lyons snapped the shafts of the spears from Morrison’s body and the expedition – what was left of it – turned for Port Moresby. Eleven days later, suffering excruciatingly, Morrison was carried into the town on a blanket. He owed his life, as he freely acknowledged, to Lyons.

On the ship taking him home he blew his nose and shot out a two centimetre splinter of wood. In Melbourne, 169 agonising days after the ambush, a surgeon removed the spearhead that was now wedged in the back of his throat. Without anaesthetic the surgeon took the tip of the spear – six centimetres long – through and up the throat and into and out of Morrison’s right nostril.

So that was that; the second-last physical reminder of what Morrison saw as his failure in New Guinea. (He was still walking around with the second spearhead in his body.) Psychologically, however, he was undoubtedly scarred. He felt he’d let down the trust that Syme had put in him, had let down the Age in the race with the Argus. He decided to leave Australia and journalism and to complete his medical studies – theoretically he had been studying medicine at Melbourne University. He sailed for London on 27 March 1884, where he had the second spearhead cut from his abdomen. ‘It was about the size of your second finger,’ he wrote to his mother, and graduated, a doctor, from Edinburgh University two and a half years later.

In the early months of 1900, thousands of Chinese members of a secret society – the Boxers – had roamed the countryside, attacking Christian missions and slaughtering foreign missionaries and Chinese converts. Then they moved toward the cities, attracting more and more followers as they came and calling for the expulsion of all foreign devils from the Celestial Kingdom. Nervous foreign ministers in the legations in Peking demanded that the Chinese government stop the Boxers. But the Boxers were acting in connivance with the old and ruthless real ruler of China, the Dowager Empress Tzu-Hsi. From inside the Forbidden City, the Empress told the diplomats that her troops would soon crush the ‘rebellion’. Meanwhile, she did nothing as 20,000 Boxers entered the capital.

In the intervening years since he graduated from Edinburgh, Dr George Morrison had roamed the world. Immediately after graduating he sailed for Canada and from there, in rapid succession, travelled and worked as a doctor in Philadelphia, Kingston, New York, Cardiff, Spain, Tangier, Ballarat, Hong Kong and Siam. In Siam, where the British and the French were vying, he worked as a British secret agent. ‘I was to travel as an Australian doctor interested in the commercial development of Siam,’ he wrote in Reminiscences, but in fact he was ‘to report especially upon the truth of the alleged action of the French government in registering the Cambodians as French subjects’. Finally his travels took him to China. ‘I went up the coast to Shanghai and then crossed over to Tientsin and Peking.’

He was 32. Time to take another walk. From Shanghai he walked 3,000 miles across China and wrote a book about it that led to him walking, finally, into the offices of Moberley Bell the manager of The Times, in Printing House Square, London. The History of The Times has this gushing but accurate description of the man Bell saw:

‘Morrison was strikingly handsome, tall and well built – a magnificent specimen of Australian manhood. Morrison, moreover, was scientific in his observation, scrupulous in his thinking, and equipped with remarkable memory. He was expert with the gun and the canoe, uniquely self-reliant and invariably unaccompanied on his explorations. His mind was candid, his writing fluent and balanced.’

Perfect, in short, for the Peking correspondent Moberley Bell was looking for.

On 16 July 1900, he was in Peking and under siege. In the compound just outside the Forbidden City’s walls there were 473 civilians, 409 Japanese and European soldiers and almost 3000 Chinese refugees, most of them Christian, ‘secondary devils’. They had just four pieces of light artillery, rifles and small arms to defend themselves.

The uprising of the Boxers, and the siege was the subject of the film 55 Days at Peking, with grim-jawed Charlton Heston playing a character inspired by the American marine, Jack Myers, who led an audacious and successful counter-attack on the Boxers. ‘A seething, polyglot mass,’ as Morrison described them, from the legations of Britain, Russia, Japan, Spain, America, Italy, France and Germany, the European diplomatic staff and their infantry could have come straight from Hollywood’s Central Casting.

There was Sir Rupert Hart, ‘after 40 years service, cooped up in the Legation, living on horse flesh and exposed to the bullets of Chinese soldiers’; Pichon, the despairing French minister (Morrison called him ‘a craven-hearted cur’); Edmund Backhouse, the son of a baronet who wrung his hands over the burning of the homosexual quarter of Peking, and who took the opportunity, in the mayhem, to purloin a priceless 600-year-old Ming Dynasty encyclopedia. There was the tempestuous German Minister, Baron Klemens von Kettler, whose assassination in the street signalled the start of the siege; and from the Imperial Palace, literally overlooking them all in the legation compound, was the scheming and bloodthirsty Dowager Empress of China.