Chapter 5

Good sports, bad sports

There were 144,319,628 men, women and children in Bangladesh on 18 June 2005 and every one of them over the age of five almost died of joy. Playing in a one-day cricket match, the Bangladesh XI soundly trounced the Australians on that historic day. It was – the experts were as one on this – the most unexpected and astonishing win in the long history of cricket.

Well, no. It wasn’t. That distinction belongs to an Australian XI – the very first eleven players selected to play for their country. And they beat England on 15 March 1877. The joy in Bangladesh 128 years later was unconfined. But the thrill that had rushed through the colonies with the news that the English had been beaten was almost palpable. Keith Dunstan, the journalist and author, has described it as cricket’s Gallipoli: 38 years before the landing at Anzac Cove, the win at the Melbourne Cricket Ground welded the colonies into one nation.

The loss, on the other hand, was a traumatic shock to the Mother Country’s psyche. It badly damaged England’s image of itself as the imperious ruler of the world, superior to all others in all ways. The very large chip which had rested on the shoulders of the young nation had been put on that of their masters. In the 310 Test matches played between the two countries since then it has remained on their shoulders.

Until 15 March 1877 it was universally acknowledged that the English could not be beaten at cricket. The game belonged to them. They invented it and they played it at a level the Australians (and the Canadians and Americans, until they came up with its cousin, baseball) simply couldn’t match. The only way to give the English a run for their money was to set the odds in your favour: play twice as many men as they put on the field. And even then, even with 22 players to their 11, they’d still beat you.

The Englishmen, not surprisingly, suffered from a marked superiority complex, tinged with more than a touch of condescension. Asked what he thought of colonial cricketers, Roger Iddison, a Yorkshire all-rounder, said: ‘Well, I don’t think much of their play, but they’re a wonderful lot of drinking men.’ This characteristic was to distinguish Australian sides for the next century and more.

But pride comes before a fall and perhaps the first premonition that the English might one day come a cropper came when an all-England XI, under Mr H.H. Stephenson, started its 1861 tour of the colonies on an unheard-of note: a team of 15 New South Wales players beat the English by two wickets. Stephenson took his team to Victoria. The Melbourne Cricket Ground astonished him: England had no oval so well prepared and so suited for cricket, and the grandstand, 700 feet long, was the finest in the world. The Victorian team of 15 promptly repeated its rival colony’s victory, and then New South Wales won again – this time by 13 wickets.

Stephenson came home humiliated. But despite the embarrassing losses the tour had been a financial bonanza and it was followed by a series of tours, each showing that the gap between the two countries was closing.

On 15 March 1877 at the Melbourne Cricket Ground that had so impressed Stephenson 16 years before, it closed emphatically. For the first time the intensely competitive colonies, New South Wales and Victoria, put aside their jealousies and agreed to play a combined inter-colonial team that would be called the Australian team. In recompense for holding the game in Melbourne and not Sydney, six New South Wales players were selected, one more than Victoria. Of those selected, Frederick Spofforth, ‘The Demon Bowler’ refused to take his place because he would not bowl to the Victorian wicketkeeper, the brilliant J.M. Blackham, and the Victorian Frank Allen, the ‘Bowler of the Century’ was not inclined to play, preferring to attend the Warrnambool Fair. The wrath of the newspapers in Melbourne and Sydney was considerable.

More than 1000 spectators were there when the match began on Thursday and by the end of the day their numbers had trebled. By lunch the Australians had lost three wickets for 41 runs and the captain, Dave Gregory, had made history by being the first man run out in test cricket. Charlie Bannerman, however, was holding things together, driving superbly while watching wickets fall. By close of play Australia was 166 for 6, and on Friday, the following day, Bannerman might have gone on to become the first man to carry his bat through a Test had he not been injured by a sharply rising ball and retired on 166, a huge total for those days. England replied with 196, leaving them 49 runs behind. Australia’s second innings was a disaster: Bannerman, his hand heavily bandaged, made just four, and the top score, from Horan, was 20.

England began its second innings needing just 154. They fell 45 runs short. Kendall, who played only one more international game (he was a wonderful drinking man) took seven for 55 in 33 overs.

One hundred years later, at the Melbourne Cricket Ground, the two teams played the famous Centenary Test. And once again Australia won by 45 runs. The chip was safe.

Big Jack Johnson, Tommy Burns was well aware, liked to start cautiously. He’d stay on the defensive for maybe four, five rounds, and then he’d build up, become aggressive. The trick was to score the points in that early round, Tommy Burns thought, and then get on the velocipede. He had the speed and the ring craft, all he had to do was stay out of reach of those long black arms. He’d done it before with men almost as big as Johnson and he could do it again. Hell, he was heavyweight champion of the world.

The Aussie referee, McIntosh, the man who was paying Burns a fortune to be in the ring with Johnson, dapper in his cap and his white turtleneck and trousers, called them in and they touched gloves. ‘Well boys, you’ve both been dying to fight each other. It’s all in except kicking and biting, so far as I’m concerned. On your way!’

McIntosh’s unorthodox departure from the referee’s standard, ‘Now I want a fair fight,’ was not a good omen. Burns looked up into Johnson’s grinning face. Johnson, he knew, was taller and heavier – five inches taller and two stone heavier – but up close, with those gold teeth – God, he was gigantic!

Still, he reminded himself again, he was Tommy Burns, heavyweight champion of the world. He was fast. He had ringcraft. All he had to do was stay out of trouble. Stay on his bicycle. Johnson was a slow starter. Box him; build up the points in the early rounds.

They came together centre ring and Burns hit Johnson with a right. Johnson took it on his biceps. He ripped a left hook, into Johnson’s stomach. It had no visible effect other than to get the big man chatting.

‘Ahl right, Tahmmy,’ Johnson said conversationally as they clinched, as if Burns had asked him to pass a slice of sponge cake, and then he caught Johnson’s uppercut and went flying through the air. It had hit him right under the chin.

The roar from the 20,000 was shattering. At once savage, shocked. This arrogant black giant had put the white heavyweight champion of the world on the canvas. And round one had barely begun.

Though he was short, Tommy Burns, a French-Canadian, was fast, ring-wise and had an abnormally long reach. Holding his hands low he would dart inside bigger, slower men to score with a punishing left hook. It was a technique that had worked well enough for him to beef up and advance successfully through the weight divisions until, in 1905, he met and, in 20 rounds, defeated the world heavyweight champion Marvin Hart.

That didn’t mean that Tommy Burns was the best heavyweight in the world. Far from it, as Johnson was about to prove, and there were other black fighters, such as Australia’s adopted West Indian, Peter Jackson, who would probably have beaten him with ease. But in the US an unwritten colour bar forbade ‘mixed fights’: white men and black men meeting in the ring.

Burns had held the heavyweight title for three years and the record for the most consecutive defences by knockout when, in 1908, the Sydney entrepreneur Hugh D. McIntosh brought him to Australia to defend his title against the local hero, Bill Squires. Burns, who acted as his own manager, had made a lot of money, and McIntosh who had made his fortune by the time he was 21, had plans to make a lot more for both of them.

To stage the title defence McIntosh built a huge open air stadium in Rushcutters Bay. The stadium and the event were a sensational success. Seventeen thousand paid to see Burns knock out Squires in the thirteenth round; the first official world championship fight staged in Australia.

Burns fought again, in South Melbourne, at a smaller replica of McIntosh’s Rushcutters Bay stadium, this time against Bill Lang and 7,000 saw him knock Bill out in six. Now McIntosh was ready for his big pay day.

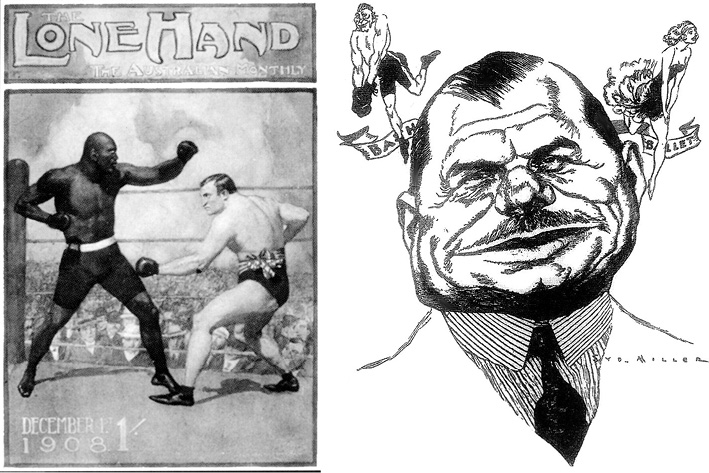

A ‘preview’ of the Burns-Johnson fight, reproduced on the cover of Lone Hand magazine. Syd Miller’s caricature of the entrepreneur who staged it, Hugh D. McIntosh, also depicts ‘Bash’ and ‘Ballet’ the two passions in McIntosh’s life. An international figure in the world of entertainment, McIntosh was an immensely wealthy man who mixed with the high and the mighty

– Courtesy of Frank Van Straten, author of Huge Deal: The Fortunes and Follies of Hugh D. McIntosh

That year, 1908, The Bulletin changed its masthead slogan from Australia for Australians to Australia for the White Man, and McIntosh, scenting big money in a fight between the reigning champion and the unofficial black champion of the world, went after Jack Johnson. He wasn’t hard to find. Wherever Burns fought Johnson was likely to turn up, sneering that the champ was avoiding him.

Arthur ‘Jack’ Johnson, from Galveston, Texas, was a superb fighter, a man with a record of 52 fights and only three losses. Out of the ring he was said to be amiable enough except when Tommy Burns’ name came up. Then he turned bitter. Because of the colour bar he could not fight Burns in the US. He had followed Burns around the world taunting him, telling Burns he could whip him if only Burns would agree to get in the ring with him outside the US.

Burns countered these taunts with the unfeasible and extremely unwise accusation that Johnson was yellow.

McIntosh had asked Burns what it would take for him to fight Johnson in Australia, and had opened negotiations by suggesting Burns take £4,000 or half the gate. ‘If I had agreed to half of it, my share would have been £13,000,’ Burns later recalled. ‘But I didn’t. I stipulated £6,000 win, lose or draw. I’ll admit it. I didn’t want to meet Johnson. I thought he was too big for me. I never thought for a moment that Mr McIntosh – or anybody else, for that matter – would put up the £6,000. I was the most surprised person in the world.

‘But having said that I would appear for that sum, I felt that as a man I was bound to do so.’

There was no problem getting Johnson into the ring: and not a lot of money was needed. McIntosh offered £1,000 and expenses and Johnson was glad to get it.

Now McIntosh had his dream bout: one that would be watched by the world. ‘The first time in history,’ as his advertisements had it, ‘that champion representatives of the black and white races have met for racial and individual supremacy.’

It was hot and humid when, at 11 a.m., Johnson entered the ring to polite applause and some boos. Burns ducked under the ropes to a primeval roar from 20,000. They cheered their hero for five ecstatic minutes. They had paid from 10 shillings for seats in the ‘bleachers’ to £10 for ringside and all of them had come to see the white man give the black giant a hiding.

At ringside were the usual mix of dilettante high society and well-heeled lowlife. ‘One-Eye’ Connelly, an American who made it a point to gatecrash major sporting events (he’d got through the guards at the gate carrying two big, empty, boxes labelled: Boxing Gloves) was there, and, among the reporters, two of America’s finest writers, H.L. Mencken and Jack London, the famous short story writer and novelist.

Johnson came into the ring wearing a dressing gown over his boxing trunks. Burns entered in street clothes and, while the crowd goggled, proceeded to strip until, to everyone’s relief, he stopped at a pair of tight cotton boxing briefs.

His elbows were bandaged. When Johnson saw this he refused to fight until they were taken off. The ‘Godfather’ of Australian boxing, Larry Foley, one of the last great bare-knuckle fighters, was at ringside and was called in to adjudicate. The bandages were against the rules, he said, but what was Johnson concerned about? They couldn’t hurt him or give Burns an unfair advantage. Still Johnson refused to go any further until they were taken off.

McIntosh warned him: ‘In one minute from now the timekeeper will strike the gong and start the fight, and if you don’t fight I will declare Burns the winner.’

Johnson scowled. ‘You can do as you damn well like!’ and turned his back on McIntosh. The timekeeper was just about to raise his hand and strike the gong when Burns jumped up and called out, ‘I’ll take the bandages off!’

He was a brave man, Burns, and he was soon to regret it.

When Jack Johnson sent Tommy Burns crashing to the canvas in the first minute of the fight he had begun a slow torture of the champion that would continue for 14 cruel rounds.

Burns bounced to his feet after the round one knockdown and flung himself at Johnson. The big man swatted him back, hitting him with left leads and right crosses as he pleased. Sometimes he’d pull him in and tie him up as he conversed: ‘Aal right, Tahmmy… poor little Tahmmy … don’t know how to fight Tahmmy?’ And he’d give that wide, golden-toothed smile as he pounded Burns’s ribs. Other times he’d stand back and say, ‘Say, little Tahmmy, you’re not fighting. You can’t? I’ll show you how,’ and he’d rip uppercuts and left and right crosses into Burns’s burgeoning and bloodied face.

It was, said the Bulletin’s man at ringside, ‘the most beastly exhibition of rubbing it in by a man determined to impress on this crowd of white trash whose champion he was beating.’

The crowd, so delirious before the fight, sat stunned and silent as Burns, more and more battered, staggered back to his corner at the end of each round. ‘Jewel [Burns’s wife] won’t know you when you go home, will she?’ Johnson told him.

By round fourteen even Johnson had tired of this, and went for the kill after Burns, down for a count of eight, had gamely struggled to his feet for more. As Johnson swarmed over Burns a police superintendent with a riding crop jumped into the ring and shouted, ‘Stop, Johnson!’ and it was all over.

McIntosh declared Johnson the winner on points.

The news swept the world. Whites were outraged. African Americans were delirious with joy. In the Deep South the news led to lynching. Texas legislated to ban the film of the fight to avert more lynching, and in Harlem there were race riots. At once the hunt began for the ‘Great White Hope’, the man who could return the heavyweight title to its rightful owners: the whites of the world.

‘There was no fight!’ Jack London wailed in print. ‘No American massacre could compare to the hopeless slaughter that took place in the Sydney Stadium. The fight, if fight it must be called, was like that between a pigmy and a colossus … of a grown man cuffing a naughty child…

‘So far as damage was concerned, Burns never landed a blow … I was with Burns all the way. He was a white man and so am I. Naturally I want to see the white man win… But one thing remains. Jeffries [James J. Jeffries, the former heavyweight champion] must emerge from his alfalfa farm and wipe the smile from Johnson’s face. Jeff, it’s up to you.’

Jeffries, who had won the title from Bob Fitzsimmons, duly came out of retirement to fight Johnson in Reno, Nevada, the following year. Hugh D. McIntosh had bid for the rights to stage the fight in Australia – a colossal $100,000 and a quarter of the film rights – but he was topped, just, by the famous American entrepreneur, Tex Rickard. McIntosh still made a pile from the fight. ‘I bet all I could on Johnson,’ he said, ‘I was convinced he could not lose.’ McIntosh won $15,000.

Jack Johnson finally lost his title to a white man, the towering Jess Willard, in 1915. It was a dubious decision and there is a strong likelihood that Johnson threw the fight. The bout was held in Cuba because Johnson had fled the US, to avoid a charge of violating the Mann Act – transporting white women across state lines for the purpose of prostitution. He returned to the US in 1920 and was sentenced to a year’s imprisonment. He died in a car crash in North Carolina in 1946.

Tommy Burns took a year off, came back to win the British Empire heavyweight title and fought five more times before retiring to become an evangelist. He died of a heart attack in 1955.

Hugh D. McIntosh made an immense amount of money from entertainment, boxing and theatre but in 1942 when he died in London, aged 65, his friends had to pass the hat to cover his funeral expenses.

The only lasting winner from the great Boxing Day Burns-Johnson fight was the dawning of the realisation among African Americans that they could hold their heads high, that one day they would fight for and win their rightful place in the US.

The Godfather, Larry Foley

Larry Foley once walked 15 miles in rain and through swamps to get to a bare-knuckle fight and famously knocked out his opponent after 30 minutes – a short and sweet affair by the standards of the day. His most famous fight, though, was at Echuca, in 1879. Foley put ’em up to an American bruiser, Abe Hickin, come to fight for the Australian championship. Hickin told the press he wanted nothing to do with the new Marquess of Queensberry Rules, boxing with gloves.

‘I want a fight, not a pillow fight,’ he said, and Foley obliged, brutally re-shaping Abe’s features. When he’d finished, the Riverina Herald reported, Hickin, ‘presented a horrible sight. Both eyes were nearly closed, his lips were cut and blistered, his nose knocked out of shape, and his whole face pounded almost to jelly.’

As Foley stepped from the ring after the fight, he was congratulated, he said, by a tall dark man who introduced himself as the champion boxer of north-east Victoria, Ned Kelly.

Kelly had indeed won that unofficial title at Beechworth. Five years before, in a long and bruising 20-round bare-knuckle bout he had stopped the aptly named ‘Wild’ Wright. A photograph taken to commemorate the bout shows a young and determined Kelly, bearded and businesslike, both fists cocked, and wearing silk shorts over ‘Long John’ underpants.

Five weeks before the Foley–Hickin match Ned and the Kelly Gang had held up the bank of New South Wales across the river at Jerilderie, and got away with £2,000. Foley’s ecstatic admirers took up a testimonial and presented him with half this amount when he beat Hickin. It was enough for him to build his White Horse Hotel and the Australian Academy of Boxing.

Hugh D. McIntosh went to Foley’s boxing school as a young man, and later told the London People magazine: ‘Under his tuition such world famous boxers as Peter Jackson, Frank Slavin Jim Hall, Young Griffo, Bob Fitzsimmons, Mick Dunn, Abe Willis and Mick Dooley spread the reputation of Australia as a home of champions.

‘It was Larry Foley who taught them to become stars. It was he who schooled and disciplined them into world beaters. His gymnasium was the Mecca to all aspirants to fistic honours. All the famous boxers congregated there; and at Larry’s Saturday night shows, where the purses ranged from £1 to £5, you saw the sorts of fights that get spectators jumping out of their seats with excitement.’

The look that lost the race of the century

Don’t tell anyone, but the first person to run under four minutes in a mile race was not Roger Bannister but John Landy. Landy would deny this. But then he would, wouldn’t he?

John Landy was the second man to run a mile in under four minutes, but the first to do so in a race. Roger Bannister did not run his sub-four minute mile in a race. He was paced by runners who were on the track solely to push Bannister under the magic four-minute mark.

John Landy beat Bannister’s time a few weeks later. He held his record for a goodly time, then he was beaten in ‘The Mile of the Century’. Then he finished third at the 1954 Olympics.

That sums up his international career.

Yet there’s a statue of him at the Melbourne Cricket Ground, one of a dozen honouring sporting heroes and heroines who had some of their finest moments at the ground. Landy’s statue stands alone, apart from the rest. His is a monument to what is finest in life.

Landy was a mile runner; in his day, the best. For decades men had tried to run a mile in under four minutes. It couldn’t be done. They could get close, but it was simply physically impossible. There was a school of thought that believed you could die trying. That was the theory.

But in the early 1950s three men determined to break the barrier even if it meant dying in the attempt. In the US, a brash young man, naturally gifted, Wes Santee, the son of a rancher, declared he would be the first to do it. Roger Bannister in England, a medical student, and Santee’s almost exact opposite, was quietly obsessed with making history; doing it for Britain. And in Australia, John Landy, a quietly modest but intense young man, the pride of the nation, was running the fastest miles ever, week in week out.

As all three came closer and closer to the magic mark the world began to watch. Their attempts were front-page news. Which of them would go under four minutes first? Or would they all fall short, as every aspirant had? Then, one of the three did it. On 6 May 1954, Roger Bannister crossed the line in 3:59.4. He was the first man to run a mile under four minutes. But he didn’t do it in a race.

Bannister ran with pacemakers – hares who set a pace that suited him, and who he followed until they dropped away, leaving him to run for the record with his famous finishing ‘kick’. The other runners were there simply to make it look like a race.

Chris Chataway a world-ranked three miler and Chris Brasher, who would win a gold medal in Melbourne in the steeplechase, were Bannister’s pacemakers, and the plan was devised in a London teahouse, by their coach, the Austrian Franz Stampfl.

Only weeks before, Bannister had made an attempt with pacemakers – one of them the Australian Don Macmillan – and had failed by two seconds. Around the world knowledgeable people reacted with scorn.

‘Maybe I could run a four-minute mile behind one of my father’s ranch horses,’ said Wes Santee.

‘Let’s keep it kosher,’ said the New York Herald Tribune, and the London Daily Mail, like much of the British press, declared the race ‘not bona fide’. British athletic officials, opposed to pacemaking for the purpose of setting records, debated whether the record should be ratified.

But they all sang a different song after 5.50p.m., on Thursday 6 May, when Bannister, Brasher and Chataway lined up at Oxford for Event Number Nine, the One Mile.

‘The gun banged, and Brasher shot forward as arranged,’ Neal Bascomb wrote in The Perfect Mile. Norris McWhirter [the public address announcer], as arranged, read off the time every half-lap. ‘He had hired an electrician to wire two speakers to the microphone, one pointing down the home straight and the other on the back straight. Bannister however, didn’t hear him correctly and felt so fired with energy in that early part of the race that he thought Brasher was setting too slow a pace…

‘In the back straight Bannister yelled, “Faster, Chris! Faster!”…As they approached the two-and-a-half lap mark, Brasher was struggling. Bannister sensed that his friend was about to stall and called for [Chris] Chataway to take over. “Chris!” Bannister yelled. Chataway was tired, but on hearing Bannister he found the strength to spring forward and Bannister passed him in the straight to win, looking like Christ crucified, in just under four minutes – 3:59.4.’

When it was over, Chris Brasher, who had a talent for getting straight to the point, told the Daily Mail’s Terry O’Connor what many were thinking. ‘Well, we did it,’ he said. ‘That means Landy and Wes Santee can never break the four-minute mile first.’

All of England rejoiced. ‘This magnificent man,’ sang the Daily Mail, which only weeks before had demanded a bona fide attempt on the record. ‘The Empire is saved,’ one editorial, quite erroneously, shrieked, and, evidently forgetting Trafalgar, Waterloo, the Relief of Lucknow and the Battle of Britain only a dozen years before, went on to bellow: ‘Roar! Roar! Roar! There’s been nothing to compare with this since the destruction of the Spanish Armada.’ In the previous year a British-led climbing team had conquered Everest (all right, technically it was conquered by a New Zealander – almost the same thing – and a Nepalese, necessary to have chaps like that along on a mountain like that.) And now a British runner had done the impossible. British joy was unconfined. ‘Only a British man could have done it, son,’ one English journalist recalled his father assuring him. It was a record, many felt, that would never be broken, unless it was by another superman. British, of course.

Forty-six days later in Finland John Landy ran a blistering 3:58 – almost two seconds faster than Bannister’s time. He did it in a race. There were no pacemakers. There was no-one helping him over the line.

The Finnish promoter of the race had invited Chris Chataway to compete. Chataway accepted and told Landy he would act as pacemaker, just as he had for Bannister. Landy was underwhelmed and unconvinced. ‘He came over to try to beat me – which is what he should have been trying to do.’ But in any case Landy had made it clear that if he had the slightest suspicion that anyone was playing the hare, with or without his approval, he would immediately step off the track.

In Australia, by necessity, Landy had always run out in front and he had told friends that he needed someone on his elbow to break the mile barrier. He had finally found that someone. ‘Chataway clung very close to me and, particularly when we began the last lap I was aware he was there and all I was trying to do was beat him,’ Landy said later. Chataway pulled up second, knowing that he had played a crucial role in breaking Bannister and Britain’s still warm mile record. Damn!

Immediately the focus shifted to the coming Empire Games. Newspapers internationally recognised that the world was about to see a race without precedent. Two men, the only two, ever to do the ‘impossible,’ racing against each other in what was quickly, and for once quite correctly, dubbed, ‘The Mile of the Century’.

The media went into a feeding frenzy. This was a sports story the like of which athletics had never known. ‘It was like a world title fight,’ Landy recalled. ‘It went on for weeks.’ The Mile of the Century was also a milestone in sporting and television history: the first time any sporting event had been televised in the US from coast to coast. A hundred million watched it in North America, a huge audience 50 years ago when only a minority of people had a television set, and millions more heard it over 560 radio stations. Time Life held its first issue of Sports Illustrated until a plane on standby rushed the photograph of the finish to the printers. In England and Australia 50 million sent up prayers.

Both men stepped up to the starting line with strategies based on their knowledge of each other. Landy’s was simple. He was going to try to run Bannister off his feet. ‘Essentially he [Bannister] ran a waiting race and usually made a long sprint with about 300 metres to go. I, on the other hand, had won my races by running fairly evenly, but nearly always taking the lead,’ Landy said.

Bannister, too, was going to run his usual race. He’d let Landy make the running. Don Macmillan, who had raced against Bannister many times, had begged Landy, his roommate at the Games, not to run from the front. ‘Roger’s going to sit you…and then jump you,’ he’d said. ‘That’s all he’ll do. He’ll sit, sit, sit. John, you’ll be a sitting duck!’ Landy thanked him and stuck to his strategy.

Landy’s plan worked better than he had anticipated up until the halfway mark. He had opened a huge gap, around 15 yards. But then Bannister began to reel him in.

‘When they rang the bell for the last lap I could see him on my shoulder,’ Landy said. ‘I knew the worst had happened and that I then had to apply another tactic. I thought he would go at 300 so even though I was running out of strength I made an effort at 300 and began to move away.

‘Coming down the back straight I was aware where Bannister was because the sun was in the right position to show our two shadows, and I could see myself moving away from him a little. I guess I wasn’t thinking clearly at that stage about the position of the sun and the fact that you wouldn’t always see the shadows.

‘When I came round the corner at the 1500 metre point, say with 120 yards to go, I was aware that Bannister’s shadow had disappeared. My first reaction was one of hope that I had got away from him – and that’s when I couldn’t resist looking back.’

Landy looked the ‘wrong’ way – over his left shoulder. Bannister at that moment was about to come in line with his right shoulder. Why didn’t he look right?

‘I looked to the left because that was the position I would be able to see where he was (as I thought he might have been) about 15 yards behind me. I looked, and he wasn’t there. I looked a bit further – all in a split second of course. When I looked up the other way he was going past my right-hand side and of course the race was all over.’

Both men had run sub-four-minute miles, but Bannister had won the Mile of the Century.

In Australia the public – every bit as parochial as the British – felt let down. Landy was faster than Bannister over a mile. Why hadn’t he run a better tactical race? Why did he look over the ‘wrong’ shoulder?

Could he have won if he’d looked right, first? ‘That’s nonsense,’ Landy said. ‘It was a matter of who slowed down first – and it was me rather than Bannister who did that…The truth of the matter is if you’re not good enough you don’t win, and that’s precisely what happened.’

Well, he would say that, wouldn’t he?

What he didn’t say was that he had cut the side of the instep of his right foot two days before the race. Jogging barefoot, he had stepped on a photographer’s flashbulb and opened a five centimetre long gash. It needed four stitches, a doctor told Landy. He could forget about running the next day. Landy told him to tape the gash and tell no-one.

A Canadian sportswriter, Andy O’Brien, had discovered Landy’s secret when he burst in on him in his room and saw the floor smeared with blood. In return for an interview he, too, had agreed to keep the story a secret. Now that the race was over he told the world, via CBS, what had happened. John Fitzgerald of the Melbourne Herald dashed to find Landy. ‘Did you step on a flashbulb?’ Landy replied, ‘How do I know if I stepped on a flashbulb? All I’m saying is I went into that race 100 per cent fit.’ He walked away. He was favouring his right leg.

He went back to Australia. He had lost interest in running. The headmaster of his old school, Geelong Grammar, persuaded him to take up a position as a biology teacher at Timbertop, the school’s secluded bush campus. There, away from the fierce focus of the press, he gradually got back his love of running.

In January 1956, he returned to Olympic Park, Melbourne and ran the second fastest mile in history, second only to his own record. A few weeks later he was set to try to smash that record in the Australian championships

There were 20,000 at Olympic Park when, in the third lap, the 19-year-old unknown Ron Clarke, caught in the hurly burly as the field bustled to go into the last 440 yards, clipped another’s heels and sprawled to the ground. Landy, running behind for one of the few times in his career and trying to hurdle him, caught his spikes on Clarke’s arm.

Landy stopped dead. He turned his back on the fast disappearing field, bent down to see if Clarke was injured. Clarke said he was fine, jumped to his feet and rushed past the stock-still Landy to re-join the race. Landy, sprinting hard, took after him. He had given the lead runner, Merv Lincoln, his greatest Australian rival, a lead of around seven seconds and 40 yards, but by the time they reached the turn he was just 15 yards adrift and into the back straight he was within five yards. He surged past Lincoln on the final turn and won by 12 yards. His time was 4:04.2

The race, and the moment when Landy stopped and bent over the fallen Ron Clarke, is commemorated in the statue at the Melbourne Cricket Ground.

The Melbourne Sun News-Pictorial’s Harry Gordon wrote an open letter that said it for all Australians.

Dear John,

The fellows in the Press box don’t have many heroes. Often they help to make them – but usually they know too much about them to believe in them. Up in the Press seats they don’t usually clap…Mostly they’ve mastered the art of observing without becoming excited. On Saturday at 4.35 p.m., though, they forgot the rules. They had a hero – every one of them. And you were it. In the record books it will look a very ordinary run for these days. But, for my money, the fantastic gesture and the valiant recovery makes it overshadow your magnificent miles in Turku and Vancouver. It was your greatest triumph.

He had one last grasp at glory. In the 1500 metres at the 1956 Olympics in Melbourne, Landy, the world record-holder for the mile, was the home-town favourite. This time, we all just knew, he’d do it. This time he’d show them! At the bell for the last lap he was in a tightly bunched field with 10 metres separating first from last. From the bunch a long-shot ‘unknown’ emerged, the Irishman Rob Delaney. He had never before run a race like it and he never again would, but it was good enough to win gold. Landy came around the final bend with plenty in reserve and belatedly sprinted into third place, his anguish and exasperation undisguised.

Later, however, Landy took it with his usual frankness and dignity. He spoke in a way that sports stars today might find incomprehensible: ‘I was disappointed, but there was no excuse. I trained wrongly and I didn’t run a very good race. But I believe that on the day, no matter how I had run, Delaney would have won.’

Well, he would say that, wouldn’t he?