Chapter 6

Mad, bad and dangerous to know

The gold pirates of Port Melbourne

Things are coming to a pretty pass indeed!’ The Argus leader writer was working himself up to a fine state of apoplexy. ‘Day by day we are wading deeper into crime, lawlessness and insecurity. The topic of today is the piratical robbery of twenty-five thousand pounds worth of gold dust: that of yesterday, a murder in Little Bourke Street; the day before, we talked of another murder at Geelong. Will tomorrow’s furnish murder in Collins Street, a ransacking of the banks, or the town on fire?’

The leader writer was in grand form and with reason: things in Melbourne Town in 1852 were indeed in a pretty pass and things were about to get worse before they got better. Half the police force were trying their luck at the goldfields where in just 30 months time there would be the armed uprising at Ballarat’s Eureka Stockade (and, simultaneously, the birth of Ned Kelly). Those police who remained in the service had to deal with a burgeoning criminal underworld fed by the yellow metal that was literally the talk of the town.

In the week that had the Argus so agitated, the big gold story, as the editorial said, was piracy: the skillfully planned and executed robbery of a ship’s cargo of 8133 ounces of gold.

Worth the immense amount of £25,000, the gold was in sealed, marked boxes in the hold of the Nelson, a barque anchored off the lighthouse at Williamstown, and that could be seen from the roof of the Argus. On 2 April 1852 the Nelson was being readied for her voyage to London carrying the cargo that was causing a social upheaval without precedent. The discovery of gold at Ballarat eight months before had emptied the town. Rich and poor, saints and sinners, sailors and servants, clerks, public servants, merchants, farmers and farriers, they were all to be found either on their way to Ballarat, prospecting on the goldfields, or back in Melbourne Town exuberantly spending, in many cases, like the proverbial drunken sailor.

At around one a.m. on the morning of 2 April, it’s fair to say, most of the sailors from the Nelson were busy getting drunk. Melbourne, a century and a half ago, was notorious for its dedication to excess. Scores of taverns, thousands of prostitutes, footpads in the alleys and highwaymen on the St Kilda road just a mile from the Town Hall: and with all this, very few policemen to stem the tide of sin.

On board the Nelson seven seamen were below in their cabins. No-one was on watch as two longboats, their oars muffled, slid silently alongside and as many as 22 men, most black-masked and armed, swarmed up the side of the barque.

Henry Draper, the first mate, was in his cabin when he was woken by Carr Dudley, the ship’s second mate, with the news that pirates had taken over the ship and all the crew on her were locked up. Two masked men verified this when they burst in and put pistols at his head, one shouting, ‘We’ve come for the damned gold, and the gold we’ll have or blow your brains out!’

Henry Draper was a brave man with an inordinate sense of propriety and responsibility: he asked the pirates to allow him and Dudley to put on their trousers, and he was concerned that the pirates might do damage to his ship. ‘As I was coming into the cabin I saw someone throw some muskets overboard, and seeing them prepare to enter the captain’s cabin, I was fearful that they would injure the chronometer or do some other damage. I wished to remonstrate with them, and therefore asked who was their captain, when they said, “We have none, and we are all captains.” At this moment one of them fired a pistol at me, and the ball inflicted a slight flesh wound in my thigh.’

This may have concentrated Draper’s mind, focusing it on the priority of keeping his brains in his skull. He took the pirates to where the 23 gold boxes were stored and they lowered them, one by one, into the longboats. They might have lowered 22 but for Henry Draper’s foolishness. One of the pirates cavalierly – why it’s impossible to guess – offered Draper the last box of gold. And Draper, that good man, said stoutly through the pain of his wounded leg: ‘I have lived honestly till now and shall take none of it.’ This was all very well, and nobly said, but the owners of the gold no doubt would have urged him to reconsider the kind offer.

‘Well,’ said the pirate, ‘if you won’t have it we will.’

And they did.

The newspapers broke the sensational story the next day after a lone sailor in hiding on the Nelson had freed the crew and sent for the police. The Argus leader writer was called in, too, and settled into his task with relish. ‘Without attempting to get up a “sensation”, or to frighten the ladies,’ he wrote with precisely that in mind, ‘we may ask if it is unlikely that the next step in this progress of villainy in Melbourne will be seizure of a vessel in the bay by a band of marauders, and the establishment of a system of actual buccaneering along our coast?’ From the banks being ransacked and the town on fire he was upping the ante now.

And the next day another Argus sensation: this time Mr Masters, a compositor in the paper’s typesetting room, was ambling along the beach not far from Williamstown when he discovered boxes in the tea-trees. He ‘immediately despatched some boys who were at hand to give information to the police who speedily arrived and brought the boxes to town. They are now lying in the watch-house, together with the stock of a gun which has been broken in two by the force used in breaking them open. A fancy pipe was found nearby, as well as a blue shirt which perhaps may afford some clue to the perpetrators of this daring deed.

‘In the hurried division of the spoil, some of the gold had been spilt about the place, and several people were employed yesterday afternoon in carrying away the sand for the purpose of washing it. One man was seen to slip away with a nugget of considerable size, and others obtained a quantity of the [gold] dust.’ Mr Masters, who probably set the type for the story, was one of them.

The clues left lying near the boxes, the fancy pipe and the blue shirt, yielded nothing. But as so often happens in ‘capers’ of this kind, the clue that undid the perpetrators of this daring deed was supplied by two of their own, informants, rumour, hunches and a considerable amount of bad luck. John George James was the first to be arrested. He was about to sail for Sydney when the Water Police caught him. Henry Draper identified him as the ringleader of the pirates and said James had pricked him with a sword. In his possession they found 20 gold sovereigns and, in his carpet bag, ‘every description of dress fitting for one who wished frequently to change his outward appearance’.

Within the week a man having an ale in the Union Inn at Geelong was approached by three strangers who came in wanting to sell gold. They emptied a pouch of nuggets onto the bar and the merchant immediately recognised them as among those he had packed for shipment not long before. Someone slipped out the back door and shortly after, the police arrived. The men were armed, they violently resisted arrest and each had a draft on the Union Bank for £500.

The gold trail led soon after to another watering hole, the Ocean Child Inn at Cowie Creek, where four men were taken after a fight, and later that day, a fifth. The evidence against all the men was largely circumstantial but they came up against the inflexible and ruthless Justice Redmond Barry, a man in whom the quality of mercy was strained. All were sentenced to 15 years hard labour.

Barry’s sardonic attitude to the strong possibility that the men were innocent – he was always inclined to believe the worst – emerges in his advice to the accused that ‘if however, any of you can show the Executive that you are innocent of the crime impugned to you, you are at perfect liberty to do so, and then, and not until then, may you hope for a remission of sentence’.

This consolation aside, Redmond Barry gave the pirates a backhanded compliment – and the Argus editorial writer a few pointers on how to keep outrage on the boil. ‘The idea of capturing a merchant vessel quietly reposing within our harbour within almost a gunshot of the shore, and abstracting from its stronghold the whole of the golden treasure with which it was freighted, was, in itself, sufficiently atrocious,’ he said, ‘but when we consider the manner of its execution, the number of the marauders engaged in it and the determination with which it was carried into effect, the character of the outrage assumes a complexion altogether new to me in the annals of modern crime.

‘It is clear that an organisation of brigands is being carried on in such a manner, and on such a scale, as to deceive even the vigilant eyes of the police, or a greater number of perpetrators of the offence of which you have been found guilty would, by this time, have been discovered.’

The vigilant eyes of the police were not deceived, however, and a greater number of perpetrators were soon discovered. Three months later three more men were arrested and tried for piracy. One was given 15 years on the roads, the other, an escaped convict, was found not guilty but returned to prison and the third was found not guilty and released.

Every one of the men had a considerable bank draft: all up police recovered more than £10,000. The remaining £15,000 was never recovered. And the remaining dozen or so pirates were never caught.

OPEN: on a dental surgery in 1865, sun streaming in through the upstairs windows of a large terrace house. A small man in his mid-twenties, a mass of dark curly hair, moustache and nervous energy, and dressed in his wife’s clothes, has a brace of pistols before him beside the surgical instruments on a small table.

He picks one up, aims, and fires.

CUT TO: a sheep’s head mounted across the room. Bones shatter and fly as the bullet crashes home.

SFX: Pistol crack, bones exploding. Then another pistol crack.

CUT TO: our hero, now lowering the second pistol, blowing the smoke from its barrel, as he does so.

HERO: ‘And now my dear Kinder, I think it’s time to call on you and your very naughty, utterly adorable wife.’

Murder can be comical. In the hands of the cinema’s master of the macabre, Alfred Hitchcock, we can laugh at what would be terrifying in real life. But the circumstances of the real life murder of Henry Kinder, you suspect, would be beyond the powers of even the Master. A movie on the killing of Kinder could be directed, and performed, only by the team from Monty Python.

Louis Bertrand, 25 years old, was an extrovert who liked to roar like a lion as he walked the streets of Sydney. When he wasn’t roaring or being overly charming, he was morose. (Today we’d know he suffered from bipolar disorder.)

Jane Bertrand, his wife, a shy, timid young woman four years younger than Louis, seemed, acquaintances gossiped, to be mesmerised by her extraordinary husband. She was asleep much of the time. (Today we’d know she suffered from narcolepsy.)

Louis Bertrand was passionately in love with the wife of his friend, Henry Kinder, an amiable New Zealander who drank too much and consequently seemed unaware that his sultry wife, Ellen, was having affairs with his friends, Louis Bertrand and an old flame of Ellen’s, Frank Jackson, and, probably, others.

Finally, there was Louis Bertrand’s dental assistant, Alfred Burne, 20, an uncomplicated young man of not much intelligence. Between these five characters – and they could be played by any number of permutations from the cast of Monty Python – you have a peerless murder farce.

Louis Bertrand’s dental practice in fashionable Wynyard Square, Sydney, was prospering when, in January 1865, he met Ellen Kinder. They fell in love almost at once. Her husband Henry, recently arrived in Sydney, was a teller with the City Bank on the corner of King and George Streets. The Bertrands and the Kinders each had two young children and the families soon became close friends – Louis and Ellen as close as it’s possible to be.

Six months later an old flame of Ellen’s, Frank Jackson, arrived from Auckland and for a time there was tension until Ellen, with both men waiting on her word, opted for Louis, and Frank, who was not in love with her, accepted her decision. Bertrand thought to soften the blow by offering Frank lodging at his Wynyard Square house with the added inducement of having an affair with his downtrodden wife, Jane. Jackson declined.

‘It’s a pity,’ Bertrand said, ‘that my wife is so virtuous. It makes it so hard to get rid of her.’

Bertrand wanted to divorce or kill Jane so that he could marry Ellen. And, of course, he told Jackson, he’d also have to kill Kinder. He’d already tried a couple of times. With young Alf Burne he’d rowed across the Sydney Harbour at night to the Mosman home of the Kinders. On the way over, a tomahawk under his coat, he’d told Burne that it was likely that Kinder would be discovered dead the next morning, and that the coroner would find he had killed himself.

Bertrand took his boots off and climbed through the window of the Kinders’ house, Burbank Cottage. He was gone for some time and Burne was asleep when he reappeared. He was in a state of irritation, as he often was. Kinder had refused to drink a drugged bottle of beer he’d bought him. They’d have to try again another night.

A week later Bertrand blacked his face, put on a red shirt and a slouch hat and a mask over his eyes and, looking like Al Jolson, Superhero, had Burne row him once again to the Kinders’. This time he told Burne he would require his assistance. Alf Burne was not very bright but he drew the line at this and Bertrand, foiled again, took a long draught of whisky and told Burne to turn the boat around; they were going home.

Louis Bertrand now decided to do the job in daylight and without assistance. Over the next weeks the dimwitted Alf Burne watched bemused as the dentist shaved his beard, dressed in women’s clothing and went shopping at a gunsmith’s. Under his master’s – or mistresses’s – guidance Alf bought a brace of second-hand pistols and handed them to Bertrand, who tucked them under his dress and bade the gunsmith g’day. With them and a sheep’s head for a target, he practised his marksmanship in his surgery. When his visiting mother-in-law heard shots in the surgery and rushed in Louis blithely told her he was conducting an anatomical experiment; he wanted to discover the thinnest part of a sheep’s skull.

On 2 October, with Jane, Louis went visiting Burbank Cottage. While Jane and Ellen chatted, Louis and Henry strolled to the pub at Milson’s Point for a refreshing ale.

Henry was still wearing a hangover from the previous night. Louis was wearing a top hat, and gloves that he did not take off for the remainder of the night. When they returned the men sat down to a game of cards over a glass of sherry. Their wives, with their backs to the card table, were on a window seat looking out over the harbour when there was a sudden loud retort.

Jane and Ellen spun around. Henry Kinder had fallen back in his chair unconscious, his ear partly blown away and his jaw shattered. Jane saw a smoking pistol at Louis’s feet as he coolly picked up Kinder’s pipe and jammed it back in his broken jaw. Ellen shrieked and ran from the room. Louis went after her, dragged her back and pointing at her bloodied husband rasped melodramatically and enigmatically, ‘Look at him well. I wish you to see him always before you!’

Then, while Jane tried to staunch the blood, Bertrand and Mrs Kinder went outside to the darkness of the verandah where they kissed passionately. When they returned and began pacing restlessly up and down, Jane handed her husband the bullet that had wounded Kinder. The three manhandled Kinder into bed and some hours later called a doctor.

At 11 p.m., when Doctor Eichler arrived Henry Kinder was semi-conscious but able to talk. Bertrand told the doctor that Kinder had shot himself, and Kinder told the doctor his wife had shot him from behind and then ran from the room. Doctor Eichler ignored this. Had the doctor the benefit of seeing endless episodes of CSI he would have noticed that the wound behind Kinder’s ear indicated the bullet was travelling upwards, meaning that unless Kinder was an India rubber man he could not have shot himself. But television was yet to be invented and the doctor was not observant and not inclined to believe Ellen Kinder would shoot her husband. He recommended to Kinder that he prepare to meet his maker.

Two days passed before the shooting was reported to the police. Senior Constable Emmerton of the North Shore police arrived at Burbank Cottage to find Henry Kinder in bed, his head heavily bandaged, and enjoying a pipe.

‘What lies are these people saying about my shooting myself?’ he asked Emmerton, while Bertrand, who was present, rolled his eyes heavenward. Senior Constable Emmerton ignored this. Outside Bertrand explained that Kinder had tried to kill himself after he and his wife had argued over another man. The policeman went away satisfied.

Two days later, however, Kinder was still alive, and even recovering. This was unconscionable! Bertrand was outraged. ‘He must not live! Bring the milk and mix the poison!’ he screamed at his wife and fell flat on his face in a fit. When he recovered he mixed either aconite or belladonna in a glass of milk and ordered Jane to give it to Kinder. Kinder died the next morning. The coroner found he had killed himself while emotionally insane.

Three months later Louis Bertrand was charged with murder. That it had taken so long was astonishing. Bertrand, of course, could not keep quiet about his cleverness. He told his sister for instance, ‘I had to kill him, I had no use for him,’ and increasingly he complained Kinder was haunting him. Detective Elliot of the new investigation branch of the NSW police force began talking to people like Alf Burne, Bertrand’s dental assistant, and Frank Jackson, who Bertrand had caused to be jailed for 12 months for trying to blackmail him.

Bertrand alone was charged with Kinder’s murder. Jane Bertrand, his frightened, wretched wife, it emerged, was often beaten by him and feared for her life, and was allowed to go free. And there was no evidence that Ellen Kinder had conspired to have her husband killed.

The jury could not reach a verdict on the first trial. Bertrand told them that the shooting of Kinder was a practical joke that had…misfired. He and Kinder had got drunk and Kinder had agreed to pretend to shoot himself ‘to amuse the ladies’. This was why no bullet was found, and Bertrand explained that the gun had been loaded only with powder and wad, and some doctors testified that a wad could have been the cause of Kinder’s wounds.

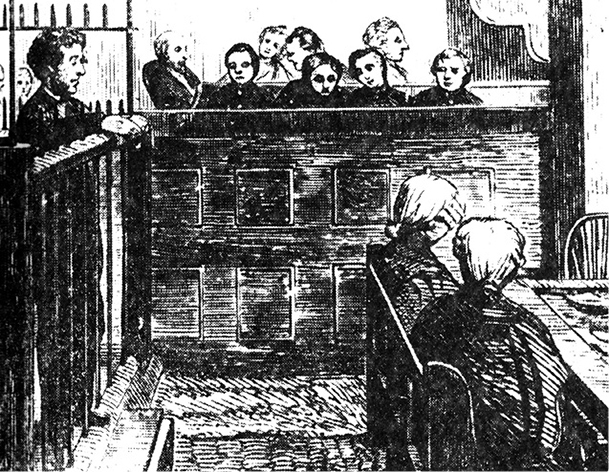

Bertrand at Darlinghurst Court in February 1865.

Bertrand’s behaviour in court was bizarre. He paced to and fro in the dock, roared with laughter at times and had to be reminded by the judge, ‘You ought to realise you are being tried for a most serious crime.’

The case went before a jury again. This time Bertrand admitted telling his sister he had to kill Kinder but, he explained, once again it was only in jest. If he had really killed Kinder he would hardly tell a woman. ‘A certain amount of intelligence and ability is imputed to me and yet it is assumed I would entrust such a terrible secret to women, who are not known to be in the habit of keeping secrets.’

He was found guilty notwithstanding this well-known fact, and in passing the death sentence on him the judge, Sir Alfred Stephens, said, ‘You cannot but be regarded as a fiend…It is distressing and sad that a father of any family should die on the scaffold for a crime that makes human nature shudder.’

Louis Bertrand did not die on the scaffold. His sentence was commuted to life imprisonment, whereupon he immediately confessed his guilt and happily told the whole story. He served 28 years in jail before being released and immediately sailing to obscurity in England – the future home of Monty Python.

The husband who murdered her wife

It’s a beloved cliché of the horror movie genre. The rain coming down, a thunderous black night lit by lightning flashes revealing a maniac muttering gibberish as he digs a grave.

In the cinema, with our popcorn in one hand and our partner on the other, and though we have seen this kind of thing many times, we still feel a frisson of unease.

But when it’s happening in real life and you’re looking on at arm’s length, drenched to the skin, shivering with fright and the cold as the thunder rumbles on and the lightning flashes across the Sydney sky, and the grave the madman is digging is just big enough for you – a 14 year-old boy – well you’d think it was strange, to say the least.

But the whole story of Eugenia Falleni, the man–woman, is strange, not least the fact that she was married for three years to Anne Burkett, an attractive young woman, before the bride noticed that there was something very basic missing in their marriage. When she did correct this oversight, when she discovered one shocking day in September 1917 that the man she had wed was not a man, she lived to regret it. But not for very long. Stranger still, after murdering Annie Birkett, Eugenia Falleni married again, and again her bride had no doubts that her husband was not, as they said in those days, ‘the full two bob’. What on earth was happening in marital beds in 1917?

Eugenia Falleni was born in Florence, Tuscany, in 1876 and went to New Zealand with her parents at an early age. At 16 she ran away to sea, told people her name was Eugene and, dressed as a man, worked as a cabin boy on a Norwegian barque. Why did she do it? Generally it’s believed she dressed as a man simply so that she could go to sea, and for the next half dozen years she carried off this deception on a variety of ships plying the South Pacific.

One man knew her secret. Martello, a fellow Italian sailor, got Eugenia pregnant in 1899 and disappeared from her life, dropping her off in Newcastle. There she gave birth to a daughter, Josephine, and resumed her life as a man. By now she was accustomed to passing herself off as a man, and as a man she was able to get work that paid considerably more than she would get as a woman. Of course Eugenia may have been a lesbian, but there is no indication of this in what we know of her private life, and the fact that her first wife, Annie Birkett, was shocked to discover her deception suggests otherwise.

Calling herself Harry Crawford, she told a childless couple called de Anglis that the infant’s mother had died and asked them to raise the girl as their grand-daughter. Sporadically, and usually drunk, ‘Harry’ visited Josephine in the de Anglis home in Double Bay, Sydney. Sometimes ‘he’ left money for her keep.

Harry Crawford was unstable and quarrelsome and drinking exacerbated his dark nature. He was in and out of menial jobs until in 1912, a Dr Clarke of Wahroonga, employed him as a general hand and coachman. Dr Clarke’s housekeeper was a pretty widow, Annie Birkett, 30, who had a young son, also called Harry. For two years Crawford courted Annie Birkett, until, in 1914, she left Dr Clarke’s, opened a corner store in Darling Street, Balmain and married him.

Soon after, Josephine moved into the Balmain home. Her guardians had fallen out over her: she was a difficult, moody girl and they couldn’t handle her. Mr de Anglis gave up, left his wife and went back to Italy and when Mrs de Anglis died Josephine moved in with her ‘father’. By this time Josephine knew Harry’s real identity but told no-one. How did it affect her? We will never know. The trauma of discovering that your father is your mother is one that few have experienced.

Inevitably Annie Birkett and Josephine fell out – not surprisingly Josephine was an unhappy, wilful teenager who defied her stepmother and her ‘father’, stayed out late at night and caused much anguish. In addition, Annie and Harry fought constantly. Annie gave up on the marriage, left home with her son and moved in with her sister in Kogarah. When Josephine found a job and lodgings, however, Harry persuaded his wife to come back and they took a house in Drummoyne.

In September, 1917, Annie breathlessly told a relative, ‘I’ve found out something amazing about him [Harry].’ What that was she didn’t say, but held the discovery secret until 28 September when she and Harry went for a picnic in Lane Cove, off Mowbray Road.

There, in a secluded spot, she was battered to death and her body thrown on to a bonfire where, three days later, a boy stumbled onto her charred remains.

The discovery of an unknown body at Lane Cove was reported and quickly forgotten. In France that week the Australians were stranded waist-deep in mud in Flanders, coming under heavy poison gas bombardment and losing 5000 in the advance on Passchendaele. In five months between Messines and the taking of Passchendaele, on 6 November, 38,000 Australians were killed or wounded in France, so one unidentified body in Lane Cove had little impact.

Harry Crawford went home and told his stepson that Annie was visiting friends and took him to Watson’s Bay. The two climbed up to The Gap and Harry, slipping though the safety fence, went to the edge of the cliff and invited the boy to join him. Young Harry declined. For some reason he felt nervous.

Now Harry Crawford was telling the neighbours his wife had run off with a plumber. He sold their furniture and moved out with young Harry to a boarding house in Cathedral Street, Woolloomooloo, where one night in the same month, October, he told young Harry they were going out.

The two walked out of the boarding house into a thunderstorm and trudged uphill through the rain. The man carrying a spade and, in his pocket, a bottle of brandy, the boy, drenched, lagging behind. Young Harry was nervous at first, when they got on a tram at Kings Cross. His stepfather sat silent, brooding, clutching the brand new spade. When they got off at Double Bay and walked into the scrub the boy was frightened. And when they came to a secluded clearing and the man started to dig he was terrified.

Despair and pain are etched in the countenance of Eugenia Falleni, also known as Harry Crawford. She duped three wives, and began to go insane when she murdered the second.

By now Harry Crawford too, was near hysterical. Taking deep swigs from the brandy bottle he handed young Harry the spade and told him to keep digging. The two kept at it, taking it in turns, while the thunder rolled and lightning lit up the lonely grave until the grave – it had to be a grave, the boy realised – got big enough for…him. Shivering, wet to the skin, he waited and Harry Crawford suddenly threw the spade into the trees and told the boy they were going home.

By now Harry Crawford was going insane, drinking heavily and having hysterics, telling his landlady, Mrs Schieblich, ‘Madam! Madam! I am haunted. I think the room is haunted!’

Shrewd Mrs Scheiblich replied, ‘I think it is your wife haunting you. I think you killed her.’ Harry slumped to the kitchen table and began sobbing. He virtually admitted killing Annie, telling his landlady he had argued with his wife and given her ‘a crack over the head’.

Mrs Schieblich was no fool. She did not go to the police. She was German and it was wise for Germans to keep a low profile at a time when her countrymen were killing Australians by the thousands. But she wanted Harry out of her house. His stepson, by now, was living safely with Annie Birkett’s sister, and Mrs Schieblich sent Harry packing when she told him detectives had called looking for him. He left the house at once.

Amazingly, in 1919, he married again, and again duped his wife who praised her ‘dear loving husband’. But Harry Birkett, now 16, and his aunt, never having heard from Annie or the plumber she was said to have eloped with, finally decided to go to the police. Dates were checked, dental remains were shown to Annie’s dentist and on 5 October 1920, three years after the fatal picnic, Harry Crawford was charged with the murder of his wife and taken to Long Bay Goal. There he was told to strip, have a bath and put on prison clothes. Harry agreed, but said he would have to do it in the women’s section.

At first the prison authorities refused to believe her. A doctor was called. ‘I knew within a matter of seconds that she was a woman,’ he announced. ‘There was not the shadow of a doubt of it.’

The trial of the ‘man–woman,’ Eugenia Falleni was a sensation. She appeared in court in women’s clothing, the first time in 30 years she had worn them. Found guilty of murder and sentenced to death, the sentence later commuted to life imprisonment, she was released in 1931 and lived the remainder of her life, in women’s clothing, as Mrs Jean Ford.

Mrs Ford bought a house in Glenmore Road, Paddington, where she lived quietly, always maintaining her innocence to those few who knew her real identity. On 9 June 1938, she stepped off the kerb in Oxford Street and was hit by a car.

No-one could trace Mrs Jean Ford’s relatives, or discover her background. They took fingerprints. The dead woman had been Eugenia Falleni.

The Desperate Housewife of Frogs Hollow

She was known, in her day, as the Borgia of Botany Bay, but this does a disservice to the Borgias – Lucretia, her brother Cesare Borgia and her father Pope Alexander VI – Rome and the Renaissance’s leading family of poisoners. Louisa Collins was from Frogs Hollow, Botany, Sydney, and she was an independent operator. Less a Borgia, more a very downmarket Desperate Housewife, she was the last woman hanged in New South Wales.

Louisa was born in 1849 to a couple employed at Belltrees, an imposing country property in the Upper Hunter Valley near Scone, where she grew up an eye-catching teenager. Twenty years on, in the dock and charged with murder, she was described as ‘pleasantly plump, with bold good looks and a flighty disposition’.

In Scone, she must have been a cracker. Charlie Andrews, the local butcher, thought so, and although Charlie was exceedingly dull and 20 years older, Louisa followed her mother’s urgings and married him at Merriwa Church of England in 1865. Charlie did his best – they had seven children – but the problem was that Charlie was a plodder and Frogs Hollow, an isolated patch surrounded by swamp and reached only by a small bridge, its population mostly wool washers, was not the place to be married to a plodder. And the problem was exacerbated by the fact that Charlie was not the only one who thought Louisa was a cracker. Those admirers tended to be located at the bar at Amos’s Pier Hotel overlooking Botany Bay, where in time Louisa became celebrated for her kindness to strangers. Soon she was installing them at the boarding house she ran while Charlie worked at the butcher shop. Frogs Hollow society was scandalised. But when Louisa took in a new boarder, Michael Collins, a 22-year-old very casual labourer from Victoria, tongues wagged so vigorously that even Charlie Andrews noticed. Louisa and Michael openly conducted their affair, canoodling on the tram and cuddling in the bushes, and just before Christmas Charlie finally seemed to notice what was going on. He wanted Collins out, and when Louisa tried to debate the matter he took Collins by the scruff of the neck and threw him out of the house. Beside herself with rage and grief at her loss, Louisa rushed off to the police station where she was told to go home and have a nice lie down.

If only she had.

Not long after Charlie found his food was disagreeing with him. He couldn’t keep anything down. The truth, of course, was that his wife was disagreeing with him. Michael Collins was calling at the Andrews home while Charlie was at work. On Monday 29 January, however, Michael Collins didn’t come around: Charlie was home, ill in bed. He couldn’t go to work and the next day Louise went to see the man from the insurance. She wanted to know, in the event of the untimely demise of Charlie, how soon she could collect the money. ‘Poor Charlie is very close to death,’ she said.

Charlie died four days later. Doctor Marshall identified the cause of death as acute gastritis and within the hour Louise was on the tram on her way to town to claim the £200 insurance money from the Australian Widows Fund. ‘I didn’t want to dwell on things over the weekend,’ she later explained in court. Somehow she found the strength to come back to the house and cook for the family and boarders and later that night called a neighbour and asked her to help her lay out the body. ‘I want you to help me with my husband,’ she began, and the neighbour interrupted, ‘How is he?’ ‘Oh he died this morning, I want you to get him ready for the funeral,’ said Louise.

Three days later Louisa held a rowdy wake at the home and when the last guest had finally left Michael Collins remained. They married almost immediately, on 9 April, and had a son seven months later, but they didn’t live happily ever after. Michael was lazy and shiftless and he was a gambler. Within 12 months he had spent all her money. She had given him her last £20 and he had gone into the city to gamble. When he came home, she said, ‘He struck a match and lit a candle and said: “Louisa, I have lost all the money.” He began to cry and I cried too.’

Their baby died suddenly, and Louisa began drinking again, telling patrons at the pub that Mick was a useless layabout. Then Mick passed away. He had complained about Louise’s drinking and she went out shopping for rat poison. In June 1888 he was in bed in agony when Dr Marshall visited. He saw Louise tenderly holding Mick’s head in bed and trickling milk down his throat. For some inexplicable reason Michael Collins was wearing his best trousers under the sheets. He refused to take them off – if he’d done so right from the beginning he and Charlie Andrews might have enjoyed life for a considerably longer period.

Dr Marshall could find nothing specifically wrong with Collins and fell back on his gastritis diagnosis, but an hour after he left Collins was dead and even Dr Marshall thought he should reconsider things. He went to the police.

Two days later, while Louise was on a drinking binge they looked around the house and found the unwashed glass Dr Marshall had seen Louise use to give Mick his milk. It was found to contain traces of arsenic, and when the bodies of Charles Andrews and the Collins’ baby were exhumed they too were found to contain traces of the poison.

Louise Collins stood trial four times for one or other of the murders with which she was charged. She claimed that Collins had killed himself – a slow suicide by poison. Such a suicide would have been a world first. But though her claim was ludicrous Louise swayed juries with her looks. ‘She is tastefully attired, cool and collected, and intelligently alert, while modest in demeanour. She can best be described as a fine looking woman,’ one reporter wrote.

Finally, on 8 December 1888, she was found guilty and sentenced to death. She went to the gallows calmly and with great courage. Her hanging was more ghastly than usual. Gruesomely bungled, it led to the New South Wales decision to never again hang a woman.

The witch who danced with the devil

Rosaleen Norton, the Witch of Kings Cross, did her damnedest to be the Wicked Witch of Oz.

She was frequently photographed with her ‘Familiar’ cat pressed to her angular face, or kneeling half-naked before an altar to Pan, the pagan god with the horns, hindquarters and sex drive of a goat. Her paintings won her singular notoriety: she is the only Australian painter ever to have her work burned by order of the censor. She conducted ‘sex magic’ covens and ruined the lives of at least two sensitive and highly creative men who were undeniably under her spell, and she is unquestionably the most famous witch Australia has known.

But Rosaleen Norton was a woman known to her friends as Roie, and you can’t be a witch called Roie. Contracting names to give them an ‘ie’ ending was the vogue when Rosaleen was one of the ‘characters’ of Kings Cross and were she living in Sydney today her friends at the Cross would undoubtedly call her Norto. Roie or Norto – either way it just isn’t a proper name for a witch.

The former Daily Mirror crime reporter, ‘Bondi’ Bill Jenkings may disagree. ‘I’d encountered her on many occasions and I reckon she was on the lowest rung of humanity,’ he said. ‘She was the epitome of depravity, but she must have had some sort of diabolical charm, because she had a circle of devoted worshippers around her…

‘She exuded evil – I used to feel like sprinkling myself with Holy Water whenever I was in her presence.’

Rosaleen was lax about personal hygiene, too, and ‘Bondi’ might have been better advised to carry a can of disinfectant. A more charitable view, from this distance, might be that Rosaleen was born before her time: she experimented with drugs, she had strong feminist inclinations and she was sexually voracious and uninhibited.

But her real appetite was for notoriety. Her gift was a very modern understanding of the cravings of the media and the sexual bent of a certain type of man and woman. She’d be a third-rate ad agency’s art director today, spicing up the shoe campaign. Or perhaps a much photographed dominatrix, seen stalking the Birdcage at the Melbourne Cup and looking sultry for the cameras at Star Wars premieres. She’d make a wonderful surprise guest on Big Brother.

Rosaleen claimed to have been born during a violent thunderstorm on 2 October 1917 with two blue spots on her left knee – the indelible mark of a witch – and a sinewy, sinister, strip of flesh running from her armpit to her waist. As an adult Roie certainly looked the part. Long jet-black hair framed plucked, arched eyebrows, high cheekbones, and a mocking, faintly malicious smirk. Her ears were pointed and her eyes were cold and dark. But she had a perfectly normal childhood with perfectly normal Protestant parents in that least satanic of towns: Dunedin, New Zealand.

That may have been Rosaleen’s problem.

The Nortons came to Sydney when Roie was seven and although she liked to say she was expelled from school for her disturbing drawings, the few known drawings of her childhood show she was a girl who liked drawing fluffy bunny rabbits in a style firmly fixed in the School of Beatrix Potter.

She was a bright student with an aptitude for drawing and won a place at the art school of East Sydney Technical College where she developed a fascination for the macabre, fed by her readings of pulp fiction such as the American paperbacks, Amazing Stories and Weird Tales, and the classics by Edgar Allan Poe, Mary Shelley and R.L. Stevenson.

At 15 she wrote three short stories good enough to be published in Smith’s Weekly, then famous for publishing many of Australia’s best writers and artists. The editor, impressed, offered her a job as a writer. Roie accepted, but then insisted that her illustrations be published rather than her stories. She lasted eight months, was fired, and when her mother died she left home. In 1935 she met 17-year-old Beresford Conroy and hitchhiked with him around Australia, supporting herself waitressing and as a pavement artist.

When the teenagers returned to Sydney they married and lived in a bohemian corner of the Rocks called, perhaps ambiguously, Buggery Barn. Kings Cross, inevitably was the next stop. She eventually made her home in a tiny, dark, basement bed-sit in Brougham Street, where she was to live for the rest of her life.

By now her conventional teenage interest in the macabre – Dracula and Frankenstein horror films were top of her pops – had led Roie to immerse herself in the study of the occult and ritual magic, the Kabbalah, pre-Christian and primitive beliefs, Satanism and Jungian psychology and such texts as Fraser’s The Golden Bough, and the perverted philosophy of Aleister Crowley (called with good reason The Beast).

She became a proponent and practitioner of ‘sex magic’ and her art increasingly mirrored her interests: a meticulous, competently drawn and painted phantasmagoria of leering satanic beings and menacing creatures, witches, and covens, naked hermaphrodites, phallic snakes and proud-breasted naked nuns who appeared to be in the wrong business. (The artist whose work in part inspired her, Norman Lindsay, is said to have called Rosaleen ‘a grubby little girl with great skill who will not discipline herself’.)

At the same time as she was beginning to explore this nether world on paper and canvas, Roie found work as an artists’ model, posing nude to cover the rent and starring at artists’ balls and parties where she rapidly became one of the ‘characters’ of the Cross – a woman whispered to be promiscuous, to take drugs and worship the devil.

Norton divorced Beresford – he’d gone to the War – in 1945 and took up with a young poet, Gavin Greenlees. Greenlees came from one of the best-known families in Australian journalism and was considered to be a pleasant fellow with promise. She had the first showing of her art in 1943, but it wasn’t until 1949 that she made an impact. At Melbourne University’s staid Rowden-White Library she showed the finest 47 pastels and sketches of her last decade. The exhibition had considerable press attention before its opening: the subject matter was a long way removed from the landscapes of Hans Heysen and Albert Namatjira then in vogue. Hardly had it opened than the Vice Squad visited and carried away four of Norton’s works: Witches’ Sabbat, Lucifer, Triumph and Individuation, and charged her with having exhibited obscene articles.

Norton won the case and got wide publicity but the show was a failure. The university restricted public access to her show and she failed to sell almost all her work. She was exasperated by press stories that she was some kind of witch and that the four paintings that had been seized had been done while she was in some kind of trance.

‘Trance nothing!’ she said, irritated. ‘Certainly I told a few arty busybodies that, because they wanted to know oh-so-much. I said I did those works after coming out of trances. Most of my stuff is drawn around witches, I’ve read a lot about witches and old folklore. But the witch stuff is tied up with those trances. It suited me and my work, and even now there are people in Melbourne and Sydney who reckon I’m a witch who can go into a trance when I feel like it.’ (Later, Roie was to recant: recycling her story of paintings-in-a-self-induced-trance to the mutual gratification of the Sydney press and herself.)

In 1951 she and Gavin settled into the tiny Brougham Street flat and the following year they jointly produced a book, The Art of Rosaleen Norton, with poems by Greenlees and illustrations by Norton.

It proved catastrophic for all concerned. The publisher, Walter Glover, had printed 500 leatherbound copies of the work but almost as soon as it was released it was declared obscene and was banned. Glover went bankrupt. Greenlees had a breakdown – he attacked Norton with a knife – and Norton, who was perpetually penniless, made nothing from the venture but priceless publicity.

The Witch of Kings Cross, as she was now dubbed, was at the height, of her Sydney celebrity status when she got a phone call from the most eminent cultural figure in Australia, Sir Eugene Goossens (see The obscene end of Eugene Goossens). His interest in her had been sparked by the furore over the banned book and artworks and his subsequent association with her – Goossens took part in her sex magic ceremonies – led to him being found guilty of importing pornography and forced to slip out of the country under a pseudonym, his dazzling career spectacularly shattered and his personal life an empty husk.

In August 1955 she exhibited at the Kashmir Cafe and the Vice Squad once again removed some paintings. Norton was again charged with breaching the Obscene and Indecent Publications Act.

A long drawn-out series of court cases followed until Norton was eventually found guilty of executing three paintings deemed to be obscene and they were ordered to be destroyed. At the same time she and Greenlees were fined £25 for assisting an unknown photographer in the making of obscene photographs, but they escaped a conviction for committing an ‘unnatural offence’ – sodomy. It was this charge, and Sir Eugene Goossens’ failure to use his influence on her behalf, that some say prompted Norton to contrive Goossens’ destruction.

As the court case against her began, a New Zealand teenager, Anna Hoffman, picked up by police in the Cross and charged with vagrancy, told them that Rosaleen had inducted her into a coven and that she had participated in a black mass. Hoffman later said she had invented the story but Norton’s reputation as the Witch of Kings Cross was now irrevocably established.

‘I yearned to be a witch and made an absolute neophyte of myself hanging around her basement flat in Brougham Street,’ Hoffman wrote years later.

‘I was hoping she would divulge to me her occult secrets. She was very generous and lent me books from her vast collection…Other times she acted mysteriously and wouldn’t even let me in the door when I called. I once smelt a secret perfume wafting from the smoke-filled room behind her. I knew she smoked hashish to open doors to her subconscious for painting, and to prepare for magical rites while in a self-induced hypnotic trance.’ (The unkind might say that Roie was in a self-induced stoned state.)

A few weeks after the Hoffman scandal Australasian Post, a national weekly devoted to pinups of girls in the newly invented Bikini swimsuits, landscape photographs of the Outback and politically incorrect cartoons much loved by men, ran a feature grimly headed: ‘Warning to Australia. Devil worship here!’ Accompanying the story was a photograph of Norton in her flat, kneeling in adoration before a larger than afterlife painting of Pan. In a lengthy interview the man from Post probed: ‘Have you ever seen the devil?’

Norton replied haughtily, ‘If you mean the being whom I know as the god Pan, I frequently have that privilege.’

Asked if she yearned for a more normal, ordinary, life she was, for once, shocked: ‘Oh, God, no! I couldn’t stand it! I’d go mad or sane, I don’t know which!’

Throughout the sixties – now without Greenlees who, in 1957, had been committed by the bluntly named Lunacy Court to a hospital for the mentally ill – Norton managed to maintain her position in Kings Cross society by dint of reports such as that in Post and this, from a 1965 paperback, Kings Cross Black Magic, purporting to describe a night at Rosaleen Norton’s coven:

‘There were about eight or nine cult members present. They all wore hideous masks so were quite willing to be photographed, although they pointed out that there were certain rites which could not be performed before outsiders or cameras.’

Rosaleen, in a cat mask, was nude except for a black apron and a black shawl. She was smoking from a long cigarette holder. Then she took off the shawl: ‘Miss Norton had modelled in her time, and she was as unselfconscious with the shawl off as with it on,’ the writer reported, not giving much away.

‘What did people get out of the coven?’ the writer asked Rosaleen, and was told, ‘I get a life that holds infinite possibilities and is entirely satisfactory to me on all planes of consciousness.’

But by the seventies Rosaleen Norton was largely forgotten and friendless, a pensioner in failing health. Richard Moir, who published a memoir of her, saw her in her last days before she died of colon cancer on 5 December 1979 at the Sacred Heart Hospice for the Dying.

‘I was ushered into the visitors lounge room, strange, I thought, as Roie couldn’t walk,’ he wrote.

‘I waited in the lounge room for some time patiently, suddenly Rosaleen Norton appeared physically standing on both legs, welcoming me, escorted by two sisters. The vision I beheld was breathtaking.

‘Rosaleen Norton (not Roie) standing there in full garb, her hair flaming back, carefully arranged in her look. Her make-up had been carefully applied, the face powder, the Rosaleen Norton full eyebrow makeup and eyebrows, the red lipstick. It was the Rosaleen Norton as I had always remembered her, but even more so.

‘She stood for only one minute…The last words Rosaleen Norton ever said to me were, “Darling: I can’t stay too long, I just came to say hello. Ah! I must go, Darling.” And with her head in a proud position Rosaleen Norton was escorted away out of my sight forever.’

But where exactly was Rosaleen going?

Surrounded by Catholic nuns in a hospital honouring the Sacred Heart of Jesus, she was heading in completely the opposite direction if she intended visiting the great god Pan.