As the year 1211 drew to a close, it was clearer than ever that there would be no quick resolution to the war by a knock-out victory and that it would drag on for some time. Wars were ever thus. For Montfort, conquest would be a matter of two giant steps forward and one giant step back, and often two or three; for the southerners, the sheer tenacity of Montfort’s professional and dedicated force meant that at best the crusaders would remain for some time a huge thorn in their flesh, sometimes digging in painfully and moving dangerously close to vital organs and arteries, and always needing to be dislodged.

The first twenty-eight months saw some of the major encounters and episodes of the whole crusade, events that shaped the nature of the conflict for decades to come. We have seen how the war was being fought, especially its constant ebb and flow, the early experiences of the commanders and their troops, and the territory that saw most of the military activity. The movement from castrum to castrum and from siege to siege; the importance of manpower and supplies; the need for active, intelligent, determined and brave leadership; the fickleness of southern lords’ pledges of allegiance: the importance of all these have been established. After Castelnaudary, the frequency of major operations and campaigns on the scale we have witnessed decreased as the war settled in for the long haul with smaller-scale activity and searches for political solutions, punctuated by major campaigns and military operations. The aftermath of the battle of Castelnaudary in the autumn of 1211 demonstrated that now the southerners had shown themselves capable of full-scale mobilisation, that the rapid benefits the crusaders could previously expect in terms of all-important momentum were no longer guaranteed, and that what they held was as insecure as they had feared. They simply did not have the manpower to garrison the region’s castra in strength with sufficient numbers of loyal troops to ensure that they could be confidently held. The year 1211 had seen the siege of Toulouse and the full-blown engagement at Castelnaudary; 1212 and much of 1213 were to see nothing on this scale, but instead a grinding away at the business of war.

Continuing military activity over the winter of 1211–12 indicates the start of this new, relentless war of attrition. This was due in no small measure to the mobilisation of the southern forces that year and the realisation that the war could no longer be either contained or curtailed. Medieval warfare is often seen as something of a seasonal sport, with the period from the onset of winter to Easter as a spell of respite, some hostilities even ending as early as harvest time. This is a myth. Warfare was far too important to be restricted in this way. Winter campaigns were common in Europe. Thus, at the end of November 1181 Count Philip of Flanders had invaded Picardy while his enemy King Philip of France was away campaigning in Champagne; after a Christmas truce, hostilities resumed in mid-January. Summer made army movements easier, but brought with it other serious problems, the chief of which was water for troops and animals, as seen at Termes. Dehydration was a major issue for men fighting in armour in the summer heat and there are accounts of men dying due to thirst and heat exhaustion. When Louis VI prepared his army for battle at Reims in August 1124, he formed his wagons into circles where men could retire temporarily from the combat for water and rest. Of course, local weather conditions were highly influential. In Languedoc, high altitudes and wind patterns could offer different conditions to the normal Mediterranean climate of the plains and valleys. In April one can clamber the heights of Montségur and place one’s hands in the snow that lies around the castle, but come down sunburnt, or stand on the ramparts of Carcassonne and freeze in the biting Mistral wind.

The southerners still had their armies in the field in November. Montfort added further reinforcements to the Alan de Roucy and the Narbonnais contingents when the ever-trustworthy Robert Mauvoisin returned to Carcassonne from a recruiting drive in the north with over 100 knights. Another fillip was the arrival of Montfort’s brother, Guy, also a veteran of the Fourth Crusade. The brothers were reunited at Castres over Christmas. Both sides could therefore remain active in the winter. But it is no surprise that Montfort tried to regain the initiative, moving back into the west to raid the Count of Foix’s lands. He raised the siege of Quié and took La Pomarède; a number of castra such as Albedun returned to his allegiance. Campaigning continued in early January 1212, with the northerners attacking Touelles, a village belonging to the despised Gerald of Pépieux. Gerald’s father was captured and exchanged for the crusader Dreux de Compans, who had been captured in the ambush at the end of 1211. The villagers were not so fortunate: Montfort ‘killed every wretch he could find there’.111 From there Cahuzac was taken, laden with supplies. The History relates how Montfort chased the counts of Toulouse, Foix and Comminges from Gaillac to Montégut and then to Rabestan, finally leaving them to retreat to Toulouse. Peter of Vaux de Cernay has Count Raymond taunting Montfort into battle, but then thinking better of it. Certainly, the southerners were very wary of full-scale engagements with the superior troops of the crusading army, but the reality was that Count Raymond was attempting, in vain, to draw all of Montfort’s forces away from Cahuzac. As we shall see later in this chapter, this was a common diversionary tactic in medieval warfare.

A meeting at Albi in February with Arnald Amalric, now Archbishop of Narbonne, led to the siege of St Marcel, 12 miles north-west of the city and another possession of Gerald Pépieux. But the allied triumvirate of the counts of Toulouse, Comminges and Foix arrived with reinforcements. With too few men, too few supplies and too many enemies disrupting communication in the area, the northerners wasted a month there, their sole petrary attacked by a sortie led by the Count of Foix. The siege was abandoned on 24 March, an inexplicable repeat of the failure before Toulouse the previous year. Montfort attempted to save face by challenging the allies at Gaillac to open battle; sensibly they refused, no doubt as expected, and he was back in Albi at the start of April to come to terms with this latest setback.

But Montfort’s fortunes changed that very week with a massive influx of crusaders from around Europe. Archdeacon William of Paris, one of the northerner heroes at Termes, and Master Jacques de Vitry had been on tour preaching the crusade. It was a great success, and this despite stiff competition from another crusade proclaimed in Castile in January at the behest of King Alfonso VIII. Luckily for Montfort, in 1212 much of Christendom had caught crusading fever; it was the year of the tragic and pathetic Children’s Crusade, one of the most notorious triumphs of cynicism and exploitation over naive optimism and ideology in the Middle Ages, according to some historians. The warrior pilgrims in Languedoc arrived from northern France, the Auvergne, Germany, Lombardy; among them were some Slavs. The sources speak of ‘incredible numbers’ and an ‘enormous’ host. And more were to appear in the spring. Montfort quickly put them to good use.

On 8 April the crusading army stood looking up at the castrum of the well-named Hautpol, high above the town of Mazamet. The elevated crags and crevices rendered Hautpol one of the more inaccessible fortifications, as Peter of Vaux de Cernay, an eyewitness to events in 1212, affirms. The crusaders took three days to assemble their petrary, which was then put to constant use. But the bombardment of stones from the heights of the ramparts was much more intense and caused the besiegers great problems and a high number of casualties. However, unlike Toulouse and St Marcel, this siege was executed with conviction and the defenders knew it. When a mist descended on the night of 11/12 April, the defenders seized the opportunity to make a break for freedom, as the defenders at Termes had done. Some made it; others did not. The victory was mitigated by two episodes: the 100 knights who came with Robert Mauvoisin, having more than fulfilled their crusading pledged, returned home; and in Narbonne anti-Montfortian riots broke out with the viscount’s 14-year-old son Amaury physically threatened and two of his men killed.

The departure of the knights was soon rectified by even more reinforcements, with contingents led by such powerful figures as Count William of Julich and Duke Leopold VI the Glorious of Austria. Burgundians, Frisians, Lorrainers, Normans and Bretons boosted the crusading host even further. So strong were Montfort’s forces he could create two armies, placing one under the command of his brother, Guy. Over the next three weeks castrum after castrum bowed down to the inevitable faced with the might of this new crusading army, either being abandoned or offering only token resistance; these included Montmaur, Les Cassès, Montferrand, Avignonet and St Michel, the last of which was totally destroyed. Count Raymond of Toulouse was in Puylaurens with a large force of mercenaries, but on Montfort’s approach he abandoned the place, which reverted back to the lordship of Guy de Lucy. Archbishop Robert of Rouen and the Bishop-elect of Laon then turned up with their forces; and especially welcome was the return of Archdeacon William of Paris. After this, Montfort continued his progress in the north of the region while his brother and Guy de Lévis moved southwards. Rabastens, Montégut and Gaillac all surrendered on the same day. As William of Tudela comments, ‘never have I seen so many castles abandoned and captured with so little fighting’.112

It was a good time for Montfort, but revenge and bitterness remained to the fore. At St Marcel he had previously suffered the taunts and jeers of the townspeople while hearing mass on Good Friday; Montfort was a devout man and this demanded retribution. He rebutted the town’s appeals to submit peacefully to him. The inhabitants fled. St Antonin refused the negotiated settlement offered by Bishop William of Albi; its lord, Adhémar Jordan, sneered: ‘Let the Count of Montfort know that a crowd of stick-carriers will never take my castrum.’113 (The southerners used ‘stick-carriers’ as a pejorative term to denote crusading pilgrims with their staves.) Montfort arrived there on 20 May; within a few hours the place was his. As at Béziers, the garrison had sortied out but were chased back by the lowly ribalds, who quickly took three of the town’s gates under their own initiative. Peter of Vaux de Cernay called it ‘a fight without swords’, as these poor pilgrims used stones, clubs, knives and axes. The townspeople received some rough treatment: at least twenty-eight were killed, many while trying to flee across the river behind the castrum (ten did manage to escape); the men and women who sought sanctuary in the church were stripped of their clothes while the clergy were harshly abused by the peasant pilgrims.

Montfort was more lenient. The castellan and his knights surrendered and were imprisoned in Carcassonne while the inhabitants were spared punishment. Here a discussion took place reminiscent of the considerations in the summer of 1209 at Carcassonne. At dawn, Montfort ‘ordered all the inhabitants to be brought out’. As they shivered with fear expecting to meet their end, Montfort consulted with his captains: ‘if he ordered the defenders, who were mere untutored countrymen, to be killed, the castrum would be devoid of inhabitants and become desolate, so wiser counsels prevailed and he released them.’114 Once again we see the cold, calculating logic behind life and death: here the military imperative was deemed best served by economic considerations. But only just. Had Montfort thought a harsh lesson took preference, the townspeople would have been slaughtered.

St Antonin and nearby castra were placed in the hands of Baldwin of Toulouse. Baldwin installed William of Tudela as canon there, where he spent the last year of his life writing The Song of the Cathar Wars. William had been with Baldwin all year and would have crossed paths with Peter of Vaux de Cernay accompanying his uncle on the crusade in 1212. The latter therefore offers even more detailed accounts for this year than usual.

With the Albi quelled, Montfort moved into the Agenais encountering little resistance: place after place was left deserted for the crusaders to destroy as part of their castle strategy, while the region’s main city, Agen, opened its gates to him. He was expanding the breadth of his operations as he moved ever further north-west into unfamiliar territory owned by the Count of Toulouse, intent on applying greater pressure on Raymond and to demonstrate to the count that his sword arm extended even here. He was able to do so because the great influx of crusading numbers had allowed him, as we have seen, to create two powerful armies, the other one led by his brother Guy operating in strength in the south.

Montfort’s progress stalled at the strong fortress of Penne d’Agenais on 3 June. The castle was, says the History, the most formidable in the Agenais, built on a huge rock and surrounded by powerful walls. In the 1190s it had been strengthened further by its previous owner, Richard the Lionheart. The place was commanded for the Count of Toulouse by Hugh d’Alfaro, the Navarrese mercenary, Seneschal of Agen and son-in-law to Raymond. With him were the mercenary captains Bausan, Bernard Bovon and Gerald de Montfabès. He had pulled in 400 mercenaries to garrison the castle in readiness for the crusaders’ inevitable arrival. Alfaro stockpiled the place with provisions and weapons, including siege machines and plentiful supplies of wood and iron. He had two smithies, a furnace and a mill constructed. He evicted the townspeople and set the bourg ablaze; Alfaro had all the men he wanted to defend the place and he did not want his resources drained by a mass of useless mouths. His duty to defend the castle for his lord overrode his duty to protect the people under his care. He was ready.

The crusaders set up camp to the south-west and moved their mangonels and battering rams into the burnt-out bourg. The machines exchanged barrages with those within the fortress, whose thick walls easily withstood the crusaders’ missiles, these only seeming to damage buildings within the castle’s precincts. The defenders made many sorties, including a failed attempt on the northerners’ petraries; the besiegers were constantly harassed. The crusading army was large but it suffered from a relatively low proportion of knights among its ranks, as its unarmed peasant soldiers were repeatedly driven away from the walls. Many crusaders started to melt away in the intense summer heat as their forty-day service expired. Montfort sent to his brother for help.

Guy had been attacking the lands of Raymond Roger of Foix along the edge of the Pyrénées. With him were the northern bishops mentioned earlier, Archdeacon William of Paris and the notoriously cruel and violent Berzy brothers. At the Cathar town of Lavelanet they massacred the inhabitants, which had the Béziers effect: resistance crumbled as they moved east towards Toulouse, ‘since all the inhabitants of the area had been quite overcome by fear’.115 Heeding his brother’s call, Guy moved north, ravaging his way across the Count of Toulouse’s lands. He left behind one knight killed in an ambush; after Guy’s departure, southern mercenaries dug up the body, dragged it through the streets, tore it apart and left it to rot in the open.

Guy encamped on Penne’s eastern side and erected a stone-thrower, bringing the total of siege engines deployed by the crusaders to about nine. But none was having much effect, so Montfort ordered the construction of a new, much bigger one under the supervision of that master of poliorcetics, Archdeacon William. As the siege moved into July, time was pressing as many contingents that had joined the crusade in May continued to return home. Some of those with Guy had only accompanied him to Penne because it was on their way back north. Duke Leopold the Glorious left to offer King Peter of Aragón his help against the Muslims in Spain. Only the Archbishop of Rouen’s force committed themselves to staying until a fresh wave of crusaders reinforced Montfort. The archdeacon set his new machine to work and the wall it targeted began to weaken, much to the alarm of the defenders. Equally worrying for them was the depletion of their water supplies, which were drying up in the summer heat and leaving them dehydrated and ill. The women and servants who had remained in the castle were evicted in the hope of stretching what little supplies remained, but the crusaders forced them back in. With no sign of relief from the Count of Toulouse, and with the prospect of being put to the sword when the castle was stormed, Hugh d’Alfaro sought surrender terms. Montfort took counsel with his commanders and the surrender was accepted; they knew their forces would continue to disintegrate at a rapid rate and there remained important business to attend to elsewhere. The defenders were allowed to go free as Montfort took possession of the place and repaired its damage with mortar and lime. It was another significant victory for the crusaders.

Peter of Vaux de Cernay’s unstinting admiration for Montfort’s finer qualities is more uncritical than usual at Penne. When Alfaro pushed out the servants and women from the castle, Peter rightly says that ‘he exposed them to the threat of death.’ Montfort, however, ‘refused to kill them but instead forced them to return. What noble and princely conduct!’ This is a rather rose-tinted view: Montfort was rarely reluctant to kill the enemy non-combatants when it served his purpose; here, it served his purpose to drive them back into the castle. Montfort refused to let the poor wretches escape as he wanted them back with Alfaro, consuming his supplies and water. He knew full well what had happened at the siege of Château Gaillard near Paris nine years earlier. Then, Philip Augustus of France was besieging the castle held by Roger de Lacy for King John. Between 1,400 and 2,000 Norman peasants from around the area had flocked into the castle for safety. When an English relief operation failed to raise the siege, Lacy knew he would not have enough food for everyone in a lengthy encirclement (it was to last nearly six months), so in November he began expelling the useless mouths, the non-combatants, out of the castle. The French let the first pathetic band of around 500 of the weakest and the oldest through their siege lines. A few days later the scene was repeated. When Philip, away at another siege, heard of this he ordered any further refugees to be forced back into the castle, just as Montfort did. The difference at Château Gaillard was that when the third group of refugees were bundled out and then pushed back by arrows and spears, Lacy kept his gates closed to them. Neither besieger nor besieged relented and the non-combatants were left exposed to the cold and wet of winter on a barren rock for three months. There followed one of the most horrifying episodes in the pitiless annals of medieval warfare. The refugees resorted to cannibalism to survive. Those who made it to spring were saved only by Philip’s return: not because the king had softened his stance, but because he wanted them out of the way of an assault and because he feared that disease might spread into his camp. The king’s chaplain, William the Breton, similarly enamoured with his hero as Peter with Montfort, praises Philip to the skies for his act: the king was ‘always kind’ to those in need ‘because he was born to have compassion towards the unfortunate and to spare them always’.116 Compassion had nothing to do with Montfort’s decision not to kill the non-combatants; he was using them as a weapon.

The campaign advanced even further from where the crusade had started three years earlier. Montfort had sent a force west under Robert Mauvoisin to successfully take Marmande, halfway between Agen and Bordeaux near the Atlantic coast, while he moved 17 miles northwards with reinforcements from Archbishop Alberic of Reims and others. At Biron he had a score to settle with Martin Algai, one of King John’s favoured mercenaries. Algai had rather peremptorily taken to his heels at the battle of Castelnaudary; having soon afterwards changed sides, he now commanded the castle of Biron for the Count of Toulouse, from where he terrorised the surrounding area. The garrison knew it could not withstand a major siege and so struck a deal with Montfort: they could go free if they handed over their commander. This saved much time and trouble; it was a neat and convenient agreement for all except Algai. He was allowed to confess his sins before being dragged through the ranks of the crusading army and hung in a meadow.

Pushing his soldiers as they struggled through the fierce summer heat, Montfort arrived before Moissac on 14 August. His wife Alice had met him en route with some infantry reinforcements. The town of Moissac does not lie in an elevated position but on level ground. The problems for the crusaders were its strong walls, abundance of clear springs and the hardened mercenaries who garrisoned it. William of Tudela writes that the townspeople wanted to submit to the crusaders but the soldiers prevented them. Both sides exchanged artillery barrages with their machines and, as expected, one of the various sorties tried to destroy those on the crusaders’ side. Montfort rallied his men to defend them; an enemy archer sighted him and let loose an arrow which struck the viscount in the foot. At one point his warhorse was killed under him and he was in danger of capture, but his men quickly saw his peril and rode to his rescue. Worse befell the nephew of the Archbishop of Reims: he was dragged back into the castrum, killed and dismembered, his body parts flung down on the crusaders from the ramparts. Any crusader caught or slain in combat was similarly hacked to pieces. There were other casualties in the combat. A young knight of Baldwin of Toulouse was struck by a crossbow quarrel that pierced his armour and ‘drove through his guts as into a sack of straw’.117

It proved an especially difficult siege in its initial stages before crusader reinforcements started to appear. Even though the sorties became less frequent, the crusaders’ working parties sent out to collect timber (for the northerner carpenters to shape into siege weapons) were still protected at all times by an armed escort; even the reinforcements had come under attack from Montauban and had to be rescued by Baldwin. Peter of Vaux de Cernay himself had a close call. While he was moving near the castrum to encourage the crusaders supplying the petraries with stones, a southern mercenary let fly ‘an extremely sharp bolt from his crossbow at maximum power and tried to hit me; I was on a horse at the time – the bolt pierced my robe, missed my flesh by a finger’s width or less, and fixed itself in my saddle’.118 Arrows and crossbow bolts were the deadliest weapons of medieval warfare.

The intensity of the siege continued unabated into September. A siege cat was the focus of much of the fighting and the crusaders broke their way through wooden palisades positioned by the ditch and guarding the barbicans. But it was momentum that undid Moissac. As news came in of other towns in the region submitting to the crusaders, the defenders knew help would not be forthcoming and that they faced an imminent storm. The townspeople sought terms. Montfort agreed to spare them if they handed over the mercenaries and the Count of Toulouse’s men. The citizens complied and paid a ransom in gold for their lives and freedom. The count’s men were taken prisoner. The mercenaries were massacred, over 300 of them. The crusaders set about this task ‘with great enthusiasm’. Much booty was gained at Moissac; the crusaders did not even have any qualms about helping themselves to the contents of the town’s monastery.

Montfort continued to press ahead with his all-sweeping momentum into the autumn. He moved south-east, bypassing the isolated but troublesome town of Montauban under the command of Roger Bernard, the Count of Foix’s son. Behind him he left William de Contres, Baldwin of Toulouse and Peter de Cissy in charge of Castelsarrasin, Montech and Verdun on the Garonne respectively to underpin his astonishing dominance of Count Raymond’s lands. His next focus was on the south and the territory of the Count of Foix. The counts of Toulouse and Foix had been causing trouble from Saverdun, using it as a base for raids around Pamiers (both places were on the road north from Foix to Toulouse). Montfort and German crusading reinforcements from Carcassonne soon put the southerners to flight by advancing on the area. The counts retreated further north, closer to Toulouse, to Auterive; but the crusaders pursued them and they abandoned this castrum, too.

Montfort kept the relentless momentum going, now turning his attention to the lands of Count Bernard of Comminges. There was only token resistance, such as the burning of a bridge over the Garonne at Muret; the town, only 12 miles south of Toulouse, was seized. From here, at the behest of the local episcopacy, he progressed into Gascony and received the submission of the Count of Comminges’s town of St Gaudens. This was followed by Samatan and L’Isle Jourdain. Montfort continued to mark his presence in the western counties of Bigorre, Armagnac and Astarac, and the viscounties of Lomagne, Béarn and Couserans – all new territories brought into the orbit of the Albigensian Crusade. Within a few days, most of the Count of Comminges’s domains went over to Montfort. His next target was Roger de Comminges, the count’s nephew, whose lands he now ravaged. From Muret and other places the crusaders were able to raid up to the gates of Toulouse itself. Toulouse was struggling under the weight of refugees, landless southern lords (the faidits), Cathars and mercenaries without towns to garrison. Monasteries and cloisters were turned into sheepfolds and stables.

Montfort ended the year with a general council held at Pamiers. Here, as conqueror of Languedoc, he oversaw the establishment of forty-six articles covering rights and rules for the governance of his new lands. These were drawn up by a commission of twelve men: four crusaders, four churchmen and four collaborating southerners (two knights and two burghers). The Statute of Pamiers was pronounced on 1 December. On religion, the church’s extirpation of heresy would be supported by the secular army where necessary and, anticipating the religious laws of Elizabeth I’s reign in Reformation England, but from the Catholic perspective, all, including lords and their wives, were compelled to attend mass and observe holy days on pain of a fine. The Church itself was to be restored all its rights and liberties. Economically and socially, the statute lowered taxes, abolished new toll gates, made justice freely available to all. The ways of the less feudally inclined south were recognised by an article that allowed serfs to be emancipated by moving into towns. Militarily, provisions were made for Montfort to call upon his vassals to perform service in the field. Among these was a clause that stipulated that the new French landholders had to provide French troops for the next twenty years. Montfort had learnt not to trust the southerners. Another clause gave Montfort the significant power to demand and receive any castrum at any time for any reason. Montfort and the northerners had laid down victors’ rules.

The southerners’ position now seemed hopeless; 1212 had been a year of unmitigated success for the northerners. Toulouse was surrounded and isolated by lands in the hands of Montfort’s men, support only available from the count’s men in the strong and still resisting town of Montauban a few miles north. Montfort had swept nearly all before him, the southerners unable to marshal an effective response. But the geographical extent of his power both belied his strength and undermined it. Winter saw the usual depletion of his forces; his garrisons would have to wait until spring to regain their strength. As it was, Foix remained unbowed and Montauban and Toulouse were stuffed full of troops who could – and needed to – sally forth on raids and test the overextended crusaders. The garrison at Montauban gave William de Contres all sorts of problems in the north-west. William of Tudela claims that they went on raids 1,000 strong; an exaggeration, no doubt, but it does denote a major force. They plundered the locality and stole sheep. Contres exhausted his men and horses tracking the enemy down, some of whom drowned crossing the River Tarn as he recovered much of their booty and freed their captives held for ransom. On another occasion, the Montauban garrison ‘overran the whole Agenais. Their troops could hardly move for the weight of stolen goods.’119 In yet another combat, Contres’s horse was struck by five or six arrows and bolts, throwing its rider to the ground.

Even the heart of Montfort’s territory was not safe. Roger Bernard, the Count of Foix’s son, operated with mercenaries between Carcassonne and Narbonne, planning to ambush crusaders. This guerrilla warfare was typical of the southerners’ tactics; while Montfort and the bulk of his forces were operating in the west, the Trencavel lands were not heavily garrisoned. Roger Bernard met one small group of new French crusaders on the road to Carcassonne. He approached them slowly so that they thought he and his men were crusaders, too. When they came close, the southerners pounced on the French and literally hacked most of them to pieces.

Others were taken off as prisoners to Foix where, says Peter of Vaux de Cernay, the southerners ‘each day applied themselves diligently to thinking up new and original torments with which to afflict their prisoners’. He heard how the French were kept in chains and cut up from one of the knights incarcerated there, who witnessed and experienced the brutality. One punishment highlighted for its cruelty involved tying ‘cords to their genitals and pull[ing] them violently’.120 For many historians, such vivid descriptions of torture are examples of monastic hyperbole; however, such acts were common in medieval warfare and deserve to be treated with the utmost seriousness.

The overextension of Montfort’s now greatly reduced force posed all sorts of military problems for the future, but the greatest weakness of all was political. Montfort’s desire to maintain his momentum by obtaining sound military objectives in the west did more harm than good. More than once before he had shown himself willing to go beyond his crusading remit, but this time the vast extent of his operations caused a major political backlash. Montfort’s incursions into the territory of Baldwin of Comminges had nothing to do with the deracination of heresy – unorthodoxy was not a problem in the count’s lands – and everything to do with isolating Toulouse. But in so doing he greatly antagonised a powerful figure whom he needed to remain neutral: King Peter of Aragón. Peter had already shown his concern over events in Languedoc, where his vassals were being hammered by the northerners. He felt that he had to tolerate much of this as he was a loyal son of the Church and himself a leading crusader in Spain; he had not, after all, gone to the aid of his vassal Viscount Raymond Roger of Béziers. But the move into Comminges’s territory was blatantly about power projection. Montfort had moved into Bigorre, Couserans, Béarn and Comminges – all places, like Foix, where Peter was overlord.

Even Pope Innocent III, that implacable suppressor of heretics, appreciated that the crusade had now gone too far. In letters dated 17 and 18 January 1213, he wrote sternly to the leaders of the crusade. To Montfort he wrote ‘you have induced to spill the blood of the just and injure the innocent, to occupy the territories of the king’s vassals’. To Arnald Amalric, now Archbishop of Narbonne and so a major power in the region, he similarly aired King Peter’s complaints to Rome:

You, brother archbishop, and Simon de Montfort have led the crusaders into the territory of the Count of Toulouse and thus occupied places inhabited by heretics but have equally extended greedy hands into lands which had no ill reputation for heresy … It does not seem credible that there are heretics in those places. The king’s messengers have added that you have usurped the possessions of others indiscriminately, unjustly and without proper care … Among these places are the territories of the Count of Foix, the Count of Comminges and Gaston de Béarn. He [Peter] has complained especially that although these three counts are still his own vassals you, brother archbishop, and Simon have sought to persuade the men of these territories they have lost to swear an oath of fealty.121

The pope ordered Montfort to restore the lands he had taken to King Peter’s vassals. Montfort’s political land grab was to be reversed.

Count Raymond, an ineffectual presence on the battlefield, had in the autumn left military matters in the more capable hands of the Count of Foix, while he used his time more productively: he slipped across the Pyrénées to press his case with the King of Aragón.

King Peter had stomached the upstart Montfort forcing himself onto the political scene in Languedoc but now he was going too far; the king was affronted. A continued lack of a robust response would undermine his authority as overlord. The year 1212 had been a good crusading year for him as well. In the summer he had co-led the Spanish and European crusaders in a crushing victory over the Almohad Muslims at the epic battle of Las Navas de Tolosa in southern Spain, the major turning point in the Christian Reconquista of Iberia. His reputation as a great crusading monarch was assured. The victory freed him to focus on his affairs north of the Pyrénées. The consequences were to be profound. The king began his journey to another major battle in 1213, this time in southern France; it was to be the biggest and most significant land engagement of the whole Albigensian Crusade.

The first half of 1213 saw a respite in crusading, a war of words replacing the war of weapons. The diplomatic activity was intense as both sides pleaded their case with Rome. At the beginning of January, King Peter travelled with a large entourage to Toulouse, where he stayed for a month. In itself, this was a strong declaration of support for Count Raymond. At an ecclesiastical council at Lavaur on 16 January, the king put forward his case for Count Raymond, who was willing to make all amends with the Church, emphasising that the count’s son was blameless and should inherit his father’s lands, and that his vassals, the counts of Foix and Comminges and Viscount Gaston de Béarn, have their lands restored (as the pope was to insist in letters written in the following two days). The council of some twenty archbishops and bishops paid little heed to the monarch. They also refused his request for a truce until Easter, understandably fearing that this would result in the supply of crusade reinforcements drying up.

Peter’s son, 6-year-old James, was still in Montfort’s court as a privileged hostage, although that term was not employed. Nonetheless, the king felt not only compelled to act but strong enough to do so: insulted at Pamiers and rebuffed at Lavaur, he now openly sided with the southerners against his new, overmighty vassal in Languedoc. The attempts to disinherit Count Raymond’s son upset many concerned about the precious rights of noble inheritance. King Philip of France was overlord of Toulouse; he was not prepared to let the crusaders dictate who should be the region’s count, even though Montfort would pay homage to him for it. As the pope reminded the crusaders, the count was still not found guilty of heresy or of Peter of Castelnau’s murder. Furthermore, the younger Raymond had powerful connections as nephew to King John of England and also King Peter’s son-in-law.

Toulouse and Montauban offered homage to King Peter to come formally under his protection, thereby making all the chief southern lords his vassals. This encouraged other southern lords to follow. And, most of all, in mid-January, Pope Innocent suspended preaching of the crusade in southern France and instead redirected all new pilgrims to the new expedition planned for the Holy Land. The Albigensian Crusade was now officially on hold. It seemed that all Montfort now had available to him was his small permanent army of colonisation and what mercenaries and local troops his funds could buy. Leaving some troops behind in Toulouse, Peter returned to Aragón and prepared for war.

According to the end of William of Tudela’s chronicle, King Peter ‘said that he would bring at least a thousand knights, all paid by him and, if he could only find the crusaders, would face them in battle … He summoned his men from his entire kingdom and gathered a great and noble company.’ William wrote, ‘And we, if we live long enough, shall see who wins and we will set down what we recall, we will continue to record the events we remember.’122 Alas, William leaves us here. His poem ends a few lines later. Sadly, our colourful war correspondent did not live to see and record the outcome of the war. His great work was left for another to continue.

News of the crusade’s suspension did not reach all quarters and some still planned to make their way south. One was the 25-year-old Prince Louis, heir to the throne of France. In February he took the cross and made his expeditionary preparations. It is thought that news may not have reached him of the pope’s decision. This is possible but unlikely as Paris would have been one of the first to know. Like his father, Louis paid little attention to the papacy when it interfered with Capetian interests. The southerners’ homage to King Peter was an insult and challenge to the French crown, the lawful overlord of Toulouse, and Philip saw the merit of combining crusading prestige in pursuance of restoring his rightful position in the south. The direct involvement of the French crown was potentially a move of enormous significance for the crusade. But Count Raymond’s international alliances came to the rescue. Philip now had papal backing to invade England, a much greater prize. John had been excommunicated by Innocent and his kingdom placed under interdict for refusing to appoint the pope’s choice of Stephen Langton as Archbishop of Canterbury. Just as Philip amassed his papally sanctioned invasion armada, John came to terms with Innocent. The pope called off the invasion, but Philip ignored him. A pre-emptive naval strike by the English on the French fleet at Damme in May put paid to Philip’s plans and left the French under pressure in the north. For the time being, Louis’s crusade was cancelled.

Just as with military affairs, so the tides of diplomacy ebbed and flowed. The crusading authorities had not accepted the pope’s judgement submissively and obediently. Montfort ignored the demands while the legates sent Theodosius to Rome to persuade Innocent of the justness of their cause. It worked. In spring the pope wrote angrily to King Peter, admonishing him for his distorted view of the situation in Languedoc and his less than full disclosure of the facts; he forbade him from interfering with the progress of the crusade in Languedoc. Now, somewhat contradictorily, he proclaimed that while he still wanted new crusaders to head east, he permitted southerners – and southerners only – the indulgence for combating heresy in Languedoc. Furthermore, in May he issued letters rescinding his instructions of January and raising the prospect of a new crusading indulgence for Occitania.

Letters from all sides crossed Europe in the pursuance of a resolution, in search of allies and to present justification of causes. All the while the southerners and the crusaders made ready for war; Count Raymond sent out word to towns to reject their allegiance to Montfort and retake control of their castra. In the spring, King Peter and Viscount Montfort renounced their feudal ties. When Lambert de Thury arrived at Peter’s court with Montfort’s letter of diffidatio, announcing his breaking of homage, the king had him thrown in a dungeon. Anger was now so high that some at court called for the killing of the messenger. Montfort rubbed salt in the wound at the end of June with the very public ceremony of the knighting of his son Amaury. This was a clear demonstration of dynastic intent and Montfort’s statement that he and his heirs were a permanent political power in Languedoc.

Montfort had already sent a party north on a recruitment drive. In May, reinforcements had started to arrive in Carcassonne. The first tranche was headed by Bishop Manasses of Orléans and Bishop William of Auxerre; with them came a force of knights that included Evrard de Brienne and Peter de Savary. With these Montfort set out to wage war once again. With too few men to invest Toulouse, he restricted himself to aggressive economic warfare in Count Raymond’s lands, ‘cutting down the fruit trees and laying waste the crops and vineyards’ and seizing and destroying seventeen castles in the first week.123 Meanwhile, Guy de Montfort besieged Puycelsi in the northern Albigeois. The castrum had twice before overthrown Montfortian rule. The counts of Toulouse, Comminges and Foix arrived with a relief army of mercenaries, hoping to raise the siege. Tellingly, they were accompanied by William Raymond of Montcade, a seneschal of King Peter. As usual, outside the walls the focus of combat was the siege engines; as at Termes in 1210, William d’Ecureuil once again found himself a solitary figure heroically and successfully defending the machines against an enemy sortie. Guy had to abandon the siege when his forty-dayers headed home. They were followed by the bishops of Orléans and Auxerre. Montfort took his newly knighted son into Gascony to bestow him with the lands he had recently won there. In his absence, and with the departure of the crusaders, the southerners became bolder in their military activity.

One of the seventeen castles taken in the spring by Montfort was Pujol, just 8 miles from Toulouse. Three veteran crusaders who had been in Languedoc since 1209 – Peter de Sissy, Simon the Saxon and Roger des Essarts – had requested its possession from Montfort, who granted it to them. Their purpose, says William of Puylaurens, ‘was to threaten the Toulousains as they attempted to bring in the harvest’.124

It is at this juncture that the unknown continuator of William of Tudela takes up the Song of the Cathar Wars. We shall therefore henceforth call him Anonymous. It is strongly believed, for good reason, that he was a soldier and troubadour fighting for either the Count of Toulouse or the Count of Foix. It has been suggested that he was Guy de Cavaillon, a close friend of Raymond’s son, the future Count Raymond VII. The Anonymous now brings a partisan viewpoint for the southerners’ side, for he hated the French and the destruction they had wrought in his beloved Languedoc. Already at Pujol he is calling the northerners ‘drunkards’.

Raymond, with his fellow counts in the triumvirate and a large force of Catalan mercenaries sent by King Peter, besieged Pujol in May. It was a large army that marked another major counter-attack. They surrounded the castrum and began the process of filling the fosse with branches and sheaves of corn, trying to keep the heads of the defenders down with a barrage of ‘feathered quarrels’ that flew into the teeth and jaws of the French; the Chronicle says that Essart was killed by an arrow wound to the head. The sappers then struck at the base of the walls with massive picks, enduring ‘blazing fire’, ‘a torrent of rocks’ and boiling water poured down upon them. The siege engines pounded away and the castle, never very strong, succumbed. The Anonymous says that the southerners stormed the place. ‘Every Frenchman there, rich and poor, they seized without mercy and put to the sword; a few they hanged.’125 He claims that sixty knights, squires and sergeants died here. Peter of Vaux de Cernay believes that the French knights surrendered when they received a firm guarantee that their lives and limbs would be spared. It is also possible that they capitulated during the final attack, when the tower of Pujol was on the point of being taken. After the surrender, Simon the Saxon was killed by the infantry; Peter de Cissy and others were spared in the slaughter and dragged off to Toulouse. But here, ‘a few days later they were slaughtered in their prison by a mob’ and ‘dragged out of the town like carrion’ or ‘dragged by horses about the city streets and then hanged from gibbets’.126 The war was now all about land and not religion; this did nothing to diminish the bitterness with which it was fought – rather, it increased it.

The southerners returned to a rapturous reception in Toulouse: they had won their first siege of the crusade. Now news arrived that King Peter of Aragón was on his way with an enormous army. Many took up the offer to go over to him as an advanced force was sent ahead to Toulouse. Montfort recalled his forces from Gascony, where his son had just taken Roquefort and freed nearly sixty crusading prisoners being held there, so as to meet the threat from Spain. As Peter of Vaux de Cernay explains, ‘the whole of the Albigensian area was now in a confused and unstable state’.127

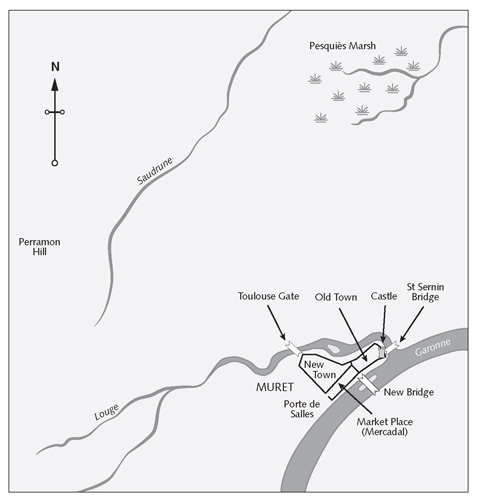

The King of Aragón’s army moved into Gascony and made for Toulouse. The city, already bursting at the seams, would not have been able to accommodate the Aragonese army within its walls; nor would it have been easy to provision it after all the crusaders’ depredations in the area. Thus, as a practical measure, on 10 September Peter set up his siege camp at his first objective of Muret, about 12 miles south of the city. This was garrisoned by a northern force of thirty knights and some infantry – hopelessly inadequate to withstand a siege of any length against the formidable army of Catalan and Aragonese troops joined by those of the counts of Toulouse, Foix and Comminges, the largest army fielded by the southerners during the whole crusade. Before long Muret was being hammered by the siege machines of the Toulousain citizen militia and the southerners quickly made their way into the town, forcing the French back into the castle. When Peter heard that Montfort was approaching, he withdrew his forces from the town, not because he was afraid of the relief force, but because he wanted it trapped in Muret, too: ‘Once he is inside there … we’ll surround and assault the town and take them all, every Frenchman and crusader.’128 Peter was planning just what William of Tudela said he would do in one of the last comments in his work.

The forced march to Muret, September 1213

Montfort gathered his maximum strength as he headed from his headquarters at Fanjeaux to Saverdun. He sent his wife to Carcassonne to muster more men; there she persuaded Viscount Payen of Corbeil to delay his return north even though he had performed his forty days’ service; he was unable to refuse a lady and so acquiesced to help Montfort. Montfort set out with seven bishops, three abbots and, more relevantly, an additional thirty knights who had just arrived from France. Among these was William des Barres, one of France’s most illustrious chivalric figures and a veteran warrior of international renown. At Saverdun, Peter of Vaux de Cernay typically depicts Montfort as eager to enter Muret that very night, but his captains advised against this: their horses were exhausted and they would be in no fit position to fight their way in should they need to. He agreed. The next morning, 11 September, Montfort rode to the monastery at Boulbonne, where he made his confession, dictated a fresh will and heard mass. The bishops with him excommunicated the allied counts – but not Peter, as only the pope could excommunicate the kings of Aragón. He then set out to Muret and the greatest battle of the Albigensian Crusade.

Muret at the time of the crusade.

The battle of Muret is one of the most important battles of the entire Middle Ages. At the time its impact was felt around Europe and accounts of it appeared in scores of chronicles. Even second- and third-hand accounts of it could be well informed as details were disseminated across the continent by the multitude of nationals who fought in the engagement. Naturally, each tells the story differently – remember Wellington’s choreographic comparison of describing a battle to describing a ball – but there is largely broad agreement on what happened.

Montfort’s force approached from the south-west and entered Muret unimpeded on the night of 11 September. Among the clergy with him were Bishop Fulkes of Toulouse, Bishop Guy of Carcassonne (Peter of Vaux de Cernay’s uncle) and the papal legate, Theodosius. Montfort and his men had anticipated trouble – they had become used to southerner attacks on convoys as their main form of retaliation – but not the new strategy of Peter to draw them in. The Anonymous admits that among Montfort’s contingent there ‘were so many good men in so small a force’; as William of Puylaurens noted, it was easy for the southerners to count the force as it went into the town. What the exact number was is hard to ascertain beyond doubt. However, there is some approximate agreement among the figures provided by Peter of Vaux de Cernay, William of Puylaurens, William the Breton and James of Aragón (the son and heir of Peter, who offers numbers in his autobiography, the earliest known to be written by a Christian king). Peter talks of Montfort’s force as being no more than 800 knights and mounted sergeants; William of Puylaurens gives a total of 1,000; James encompasses both with a range between 800 and 1,000 knights; while William, in the more reliable of his two works, records 260 knights, 500 mounted sergeants and, the only one to do so, 700 infantry composed of pilgrims rather than trained troops. Thus Montfort’s force probably comprised about 800 heavy and light cavalry (and perhaps as many as 1,000) and some 700 relatively inexperienced infantry. Of the opposing Aragonese and Occitanian forces, the best-informed guesstimate puts these at some 1,600 to 2,000 cavalry (and perhaps as high as 4,000) and between 2,000 and 4,000 infantry militia. Thus, at worst, the crusaders were outnumbered by five-to-one; at best, by just over two-to-one. The highest ratio is unlikely, given that not all of Peter’s forces were drawn up on the battlefield. Of course, Catholic commentators at the time portrayed the imbalance as approaching twenty-to-one, so as to exaggerate the extent of the challenge faced by the crusaders.

Montfort’s position was not a comfortable one, hence his overtures to King Peter for talks of either a truce or a peace. This was in all likelihood a stalling tactic partly in the hope that he would receive further reinforcements (that night the Viscount of Corbeil arrived with thirty knights) and partly in the hope that dragging out negotiations would cause some of Peter’s forces to drift away. Ultimately, as William of Puylaurens rightly noted, ‘Count Simon thought it likely that if he gave Muret over to his adversaries the whole territory would rise against him and join the other side, which would create a dangerous situation.’ He accurately captures Montfort’s typical, belligerent attitude: ‘he thought it better to risk all in a single day rather than strengthen the courage of his adversaries by ineffectual temporising.’129 King Peter, confident in the might afforded by the largest anti-crusading army of the whole conflict, rejected all of Montfort’s approaches out of hand.

The monarch appeared remarkably relaxed as the decisive battle loomed. Even his son reports him as having ‘lain with a lady’ just before going into combat.130 Peter was an infamous womaniser, making it easy for the crusaders to make of him a propaganda target, depicting him as under the sway of women and even of fighting the war for a ‘harlot’. Montfort’s preparations were, of course, altogether more austere and pious, taking every opportunity to jump into a chapel rather than a bed, offering up his prayers to God. Peter, by contrast, when having finally made it to mass, is reported by his son to have been incapable of standing for the Gospel, so spent was he from his lusty exertions.

The sources provide us with a detailed account of the two opposing leaders on the morning of 12 September as they made ready for battle. The anonymous continuator of the Song tells of a grand council held in a meadow at which the king addressed the counts of Toulouse, Foix and Comminges (together, he omits to add, with all the Aragonese nobles who had accompanied him). Here the battle orations began. ‘Be ready, each one of you,’ he exhorted them, ‘to lead your men and to give and take hard blows. If they had ten times the numbers, we should make them turn and run.’ Count Raymond, unsurprisingly, cautiously advised a more defensive strategy: ‘Let us plant barricades around the tents so that no cavalry can get through; then, if the French try to attack, we first use crossbows to wound them and as they swerve aside, we make our charge and rout them all.’ He did not think any major engagement was necessary as the crusaders would eventually be starved out of Muret anyway. But one of Peter’s leading commanders, Michael of Luesia, a hero of the great victory at Las Navas de Tolosa the year before, snorted contemptuously at this hesitant plan and talked of cowardice among the southerners. They would instead go immediately on the offensive. The cry of ‘To arms!’ went up and they began their approach to the town.

Meanwhile, Montfort had similarly taken counsel, as he always did, and he and his men heard mass and went to confession. Our three main war reporters do not record any rousing speeches by Montfort – the History has its hero simply say, ‘Today I offer my soul and body to God’ during one of his many visits to chapel131 – but William the Breton offers a lengthy and almost certainly imagined oration by Simon, calling on the descendants of Charlemagne and Roland to vanquish the enemies of the true faith. His speech, focused very much on the honour and prowess of leading northern French noblemen, warned that defeat would mean certain death and that the enemy would ‘disperse our bodies to be devoured by the beasts of the forests and by birds of prey’.132

Southerner cavalry and Toulousain infantry militia launched their first wave of attack against Muret, taking advantage of the fact that the main gates to the new town had been left open for an episcopal delegation of the bishops with Montfort to make a direct appeal to Peter. (While pursuing this one last diplomatic effort to avoid battle, they had put the services of their clerical entourages to more practical purposes, adding their energy to building up the town’s defences.) The attack was repulsed after a combat in which ‘both sides made blood spurt so freely that you would have seen the whole gate dyed scarlet’, says the Anonymous.

It seems to have been at this point that Montfort finally decided on his plan of action. The Song has him claiming to have spent the entire previous night lying awake trying to decide what to do. His typically bold plan was to ‘make straight for their tents, as if to offer battle’. If that failed, ‘then there’s nothing we can do but run all the way to Auvillar’. With that, Montfort ordered his cavalry to saddle up. On raised ground, so that he was seen by his own men and the enemy, Montfort had his horse brought up and went to mount it. As he did so, the stirrup strap of his saddle broke and had to be repaired. This was followed by another bad omen on his second attempt: his charger suddenly raised its head and hit Montfort on his forehead, temporarily stunning him. The horses of the heavy cavalry wore armour and forms of protection, so the blow was quite heavy. This was actually the third ominous portent that had befallen Montfort immediately before the battle: earlier, while kneeling to pray in chapel, the leather binding of his leggings had snapped. The public embarrassment around the mounting of the horse must have unsettled his men as much as it delighted the predictably mocking southerners.

The Bishop of Toulouse then began to bless the crusader knights one by one. But Bishop Guy of Carcassonne, recognising the delay that this would cause, took the crucifix from his fellow bishop and blessed them en masse, promising Heaven to any who fell that day. While reviewing his troop, a knight advised Montfort to determine the size of the enemy forces before going out to meet them. This was standard practice, but Montfort dismissed the precaution. His mind was set on action and nothing should now delay the moment of truth. The Anonymous reports that Count Baldwin, the estranged brother of Count Raymond, urged the crusaders to ‘be sure and hit hard. Better death with honour than a life of beggary’. On this, Montfort ordered his infantry to remain behind to defend Muret as he led his cavalry out of town and onto the field of battle.

It is likely that, as the Song says, the crusaders left Muret from the Salles Gate on the town’s south-west side; this shielded their movements from the besieging Toulousain forces to the north. Here they formed up in the traditional three battalions – or ‘battles’ as they were known – for engagement. William des Barres, from a great chivalric family renowned throughout France, was given command of the cavalry in the front line, while Montfort headed the tactical reserve at the rear. The middle battle was commanded by Montfort’s veteran captain, Bouchard de Marly. This was not timidity on Montfort’s part – his personal courage had been proven beyond doubt on numerous occasions – but the usual positioning of the battlefield commander; from here, he could direct his troops, send out orders and launch his own battle into the fray where he thought it could best be used. Thus formed, William of Puylaurens says, they initially made a feint away from the enemy, to give the impression that they were retreating. William the Breton, however, says the crusaders ‘headed straight for the enemy battalions like a lion’. Either way, they emerged from behind the wall, crossed the Louge, which feeds the Garonne, and advanced. Behind them they left the clergy praying for their victory; Peter of Vaux de Cernay says the latter created a deep roaring sound like a howling.

Facing them about a mile across the plain to the north-west of town were the ordered ranks of the enemy, similarly drawn up in three ranks. Count Raymond Roger of Foix led the first line of Catalans. Count Raymond of Toulouse was deemed too elderly to submit himself to the rigours of battle, so he withdrew towards the high ground of the encampment from where he could watch the battle. King Peter placed himself in the middle rank, a decision commented on by both contemporaries and historians. If the battalions were placed across the battlefield in line, even if staggered, rather than in column, this would make sense. However, the protection afforded to his flanks by the small River Saudrune on his right and by the Pesquiès Marsh to his left might also hinder his flight should this prove necessary. The river, little more than a stream, was not a major obstacle in itself, but in a rout the best crossing points could quickly become bottlenecks, and the banks would rapidly becoming slippery and boggy. At the battle of Towton in 1461, the retreating Lancastrians were slaughtered trying to cross a small beck close to the battlefield, their corpses forming a bridge of bodies. Furthermore, the western bank of the river soon rises up to an escarpment, which again would cause congestion in a retreat. The quick escape route from the battlefield was thus directly behind the centre. Peter’s position was also strong in that it held the crest of a small rise, which gave him a good vantage point.

More notable is Peter of Vaux de Cernay’s remark that the king disguised himself by wearing the armour of another knight. This was not common but not unheard of. On the one hand, a king’s visual presence on the battlefield was important to his captains and troops, encouraging them to fight on; on the other, it did rather mark him out to the enemy. It was common practice to target an enemy king, as was to happen the following year at Bouvines. On that occasion, a squad of knights was formed with the sole intention of fighting their way through to either kill or capture King Philip of France. Although they did not break through, they formed a breach that allowed infantry to do so; catching his mail armour with a billhook, they pulled the king to the ground. He was saved only by the intervention of his bodyguard, who threw himself on top of Philip as a shield. The bodyguard died but bought enough time for Philip to be rescued. Capture would entail a massive ransom (as paid for King John II of France and Richard the Lionheart of England) as well as a complete transformation of the political scene. But disguise brought its own dangers.

Des Barres and Marly crossed the plain and plunged into the alliance ranks with their battalions, the one following the other into the fray, creating the waves of shock charges for which the Montfortian heavy cavalry was known. They both struck so deeply that they soon disappeared from Montfort’s views as they penetrated the enemy divisions. William the Breton says that the Aragonese and southerners re-formed their ranks so as to encircle the northerners, while William of Puylaurens states that the impact of the crusader charge was so great that the southerners were given no chance to regroup in their rear line. The combat was ferocious. The bellicose Breton gleefully reports ‘naked swords plunging into guts’. He is the only major source to speak of infantry; these would have been used by the southerners in ranks of spearmen to protect the knights. William describes how the knights attempted to knock the enemy cavalry to the ground so that the footsoldiers could despatch them, tearing out their entrails and cutting their throats. The horses were also targeted in an endeavour to bring down the riders, many mounts being killed or covered in wounds.

Montfort then made his move, ordering his battalion to advance to the right. To get to the enemy he had to cross some marshy land and a ditch; his way was eased by a pathway across these. He then unleashed his cavalry force into the left flank of the enemy as another full-scale mêlée ensued. The History gives a taste of the scrappy hand-to-hand fighting Montfort faced:

As the count was attacking them, they struck him from the right with such violent blows from their swords that his left stirrup broke. He tried to fix his left spur in the horse-blanket, but the spur itself broke and fell away. The count, who was a very strong knight, kept his seat and struck back against his foes vigorously. An enemy knight struck him violently on the head, but the count immediately hit him under the chin with his fist and forced him off his horse.

Back among the other divisions, the King of Aragón was in mortal danger. William and the Anonymous agree that the crusaders saw the king’s standard and successfully fought their way towards it as the crescendo of battle filled the air. They set upon him; whether they recognised him or not is unclear. Peter tried frantically to identify himself with screams of ‘I am the king!’ but, relates the Song, ‘no one heard him and he was struck so severely wounded that his blood spilled out on the ground and he fell his full length dead’. According to the less well-informed William the Breton, who at one stage fancifully imagines a personal one-on-one combat between Peter and Montfort, a squire named Peter, fighting on foot as his horse had been killed, approached the king and, ignoring his pleas for mercy, plunged his sword twice into his neck. Later in the century the honour of the kill would fall, according to Gérard d’Auvergne’s chronicle, to Alain de Roucy.

The king struck down, together with Michael of Luesia and many other nobles, the Aragonese turned to retreat. Already, on their left wing, the Count of Foix was leading his troops in a headlong flight from the battlefield, pursued by Montfort. The viscount sensibly advanced relatively cautiously lest the enemy regroup and counter-attack: he did not want his men too dispersed to re-assume their battle formation. Des Barres and Marly’s pursuit was more rapid, and southern casualties all the higher.

But the fighting was not yet over. Back at Muret, Toulousain forces were pressing to break into the town; if that were to be lost, the victory on the battlefield would have been a dramatic but hollow one. The besiegers were confident, not knowing at this stage the outcome of the battle. Bishop Fulkes of Toulouse tried to reason with his fellow citizens, sending out a priest to urge them to lay down their arms. Their response was to knock the messenger about with their spears. They soon rued their actions. They did not realise who had won the clash on the plain until the crusaders returned to Muret bearing the standards of the Aragonese and southern forces. The crusading army now turned its attention on them.

Montfort’s cavalry, possibly assisted by the garrison infantry, chased down the Toulousains. The latter abandoned their fortified camp and rushed to their barges on the River Garonne. Those who could thus made their escape; but many did not. Most who failed to get away on a barge were either cut down or drowned in the river. After long years of dangerous campaigning and grievous losses, the crusaders were in no mood to show mercy. William the Breton says that they did not stop to loot the camp (that came later) or take prisoners; instead, they focused on ‘reddening their swords with blows, taking the lives of the vanquished and shedding their blood’. The Anonymous reports that Sir Dalmals of Creixell, part of King Peter’s intimate inner circle of advisors, jumped into the River Louge, shouting ‘God help us! Great injury has been done to us, for the good King of Aragón is dead and defeated and so are many other lords, all defeated and killed. No one has ever suffered such a loss!’

Chronicles misleadingly claim that some 15–17,000 southerners were killed – far more than the total of combatants on both sides. On crusader casualties, William of Puylaurens claims that not ‘even one man on the Church side fell in battle’. Roger of Wendover repeats the evaluation given by the prelates present in a letter disseminated across Europe: ‘a correct account of the number slain cannot be given by any means; but of the crusaders only one knight and a few sergeants fell’.133 Guillaume de Nangis is more specific, reporting only eight fatalities on the French side. It was clearly a complete rout. With total victory assured, and their sword arms exhausted, the northerners took to gathering up prisoners and plunder, which Montfort shared out among his men. Many of the captured were ransomed; others were to die in prison. The Chronicle reports that ‘it was pitiful to see and hear the laments of the people of Toulouse as they wept for their dead; indeed, there was hardly a single house that did not have someone dead to mourn, or a prisoner they believed to be dead’. News of the battle was to spread swiftly beyond Aragón and Languedoc throughout Europe, the Anonymous claiming that ‘news of this disaster echoed round the world’. As the crusaders made their way to church to give thanks to God for their victory, the naked body of King Peter, stripped of armour and anything of either monetary or gruesome souvenir value, was retrieved by the Knights Hospitaller and prepared for burial.

Montfort’s decisive action at Muret once again shows him as the embodiment of military command. His decision to engage the enemy at Muret has sometimes been considered unnecessarily perilous and risky, vindicated only by its improbable success. Significantly outnumbered, and, in the King of Aragón, facing his most experienced, powerful and successful opponent yet, the seemingly sensible option would have been to hold up behind the walls of Muret, the benefits of defence hopefully negating the enemy’s numbers. Although the problems of provisions would weigh heavily on the crusaders – remember William of Breton’s maxim ‘famine conquers all’ – the Aragonese and Toulousain forces would also have supply problems, especially with such a large army to feed. Disease would threaten those outside the walls as much as those inside them. The greatest clear advantage for Montfort was the potential for the southern alliance to fracture: the Occitanian counts had other affairs to attend to; the militia was away from its families and work; and Peter had a kingdom to run. The last factor was the most important: without the king, the southerners would have been extremely hesitant to face Montfort in open battle. The danger for them was that Peter would return home to attend to his concerns there (especially the Reconquista) as he had done before. It was his involvement in the great victory at Las Navas de Tolosa the previous year that freed him to make a full-scale intervention in Languedoc, but the full implications of this triumph were still unclear. The Almohad advance north had been decisively halted, but the temporary alliance of Navarre, Castile, Portugal and Aragón that had achieved the victory was a rare moment of temporary unity.

Without the benefit of hindsight, was Montfort’s decision to force battle indeed a rash one? No. It made good sense on a number of levels. For a start, it was neither a hasty nor an idiosyncratic choice: the sources attest time and again to Montfort consulting with his commanders in a war council before taking any course of action and even altering his position because of their reasoning. The plan was a joint one, made by leading knights with impressive military experience. All were acutely aware of the gamble, but the consequences of a lengthy siege seemed to present the greater risk. Manpower was a perennial problem for Montfort; as forty-dayers completed their service and departed, he may have been in danger of becoming even more outnumbered. This problem was made all the more acute by Pope Innocent’s focus on a new crusade to the Middle East, which would deplete the pool of potential recruits in Languedoc even further.

Two reasons dominated Montfort’s thinking. The first was purely tactical. The northerners had a proven advantage on the battlefield, even when outnumbered: the shock charge of their heavy cavalry. This was a formidably effective tactic. The combined mass and momentum of experienced armoured knights and trained warhorses, packed tight in disciplined serried ranks and crashing into the enemy lines, constituted an overwhelming force, as the French had demonstrated at Castelnaudary. We have seen how the charge of des Barres and Marly penetrated deep into the enemy ranks at Muret. This advantage of discipline and training was admitted by the future James I of Aragón (at this time a hostage under Montfort’s roof and later an outstanding general), who explained his father’s defeat at Muret thus: ‘Those on the king’s side knew neither how to place order in the lines nor how to move in formation, and each noble fought for himself, and broke with the rules of arms. And because of their disorder … the battle had to be lost.’134 Another factor was that Peter’s army was not drawn up to its full extent: Count Nunó Sanchez and Viscount William de Montcada had not yet arrived at Muret and sent word to the king that he should wait for their arrival before engaging in battle (advice that was ignored). Perhaps Montfort’s scouts and spies knew this, further persuading the crusaders to strike before their enemy’s numbers increased even further.

The second reason was strategic and concerned the all-important phenomenon of momentum. Repeatedly Montfort had seen his great gains swept away, only to have to painfully win them back again. Delay at Muret would only weaken his precarious hold of Languedoc: it would reveal the weakness of his overall position as he had to concentrate his forces near Toulouse. Elsewhere throughout the south those hostile to French rule, encouraged by Montfort’s enforced absence and by the powerful alliance now ranged against him, would, as they had so often done in the past, seize the opportunity to retake control of their castra. Like dominoes, when one fell the others would follow in swift succession. Montfort knew that behind him many who resented the northern invasion were waiting and willing to see him tied down and defeated at Muret. As noted above, William of Puylaurens put his finger on the danger when judging that events at Muret could result in the whole territory rising against Montfort and joining the other side. Delay risked losing all.

Peter’s decision to join in battle mirrored Montfort’s. He wanted to strike while he had the advantage of numbers and while he had such a large army mustered and ready for combat; he did not want to postpone the engagement lest his force dissipate during a siege. Besides, when the French attacked, the Aragonese and southern forces had little choice but to defend themselves; the only alternative was to scramble back into their encampment on the heights, which would have been a humiliating and unconscionable decision, and one that would have given a massive morale boost to the French. A Spanish historian has suggested that Peter ignored any counsel not to fight on the day because a victorious battle would bolster his reputation beyond dispute: having defeated the Muslims at Las Navas de Tolosa, he was already clearly a Catholic hero, and he wanted to capitalise further on this. Defeating Montfort at Muret would demonstrate to the papacy and all of Christendom that God was indubitably on his side against the French, just as He was against the Almohads. With such a divine seal of approval, Peter’s ambitions for a Catalan–Occitanian empire could become a reality. For, again, we need to see the conflict itself in a territorial rather than a religious light. The stakes were huge: for Peter, it meant massively extending his influence and proto-imperial reach; for the crusaders, it meant the chance to consolidate their conquest of Languedoc.

Both sides were fully aware of the capricious fortune of battle. Count Raymond’s defensive policy was not timid or cowardly as Michael of Luesia, now lying dead on the battlefield, had declared; rather, it was the standard strategy of battle avoidance to which commanders adhered as a general practice. Once contact had been made with the enemy ranks, little control was left to the commander. In the confusion of battle, trust had to be placed in the battalion commanders and their tactical units and lieutenants. Banners, heraldic devices and surcoats helped to identify individuals, but often little could be done to alter what was already in progress by those in the thick of the mêlée. Hence the need for tactical reserves, as Montfort showed at Muret, from where the commander could see the bigger picture of the engagement and deploy the reserve where it was most needed.

A commander might wish to avoid the danger of being killed or captured in battle – hence Peter’s disguise. Harold Godwinson, Richard III and Peter of Aragón all met their end in combat, and many others, such as Henry V and Philip II of France, had close calls. Henry VI, Edward IV and King Stephen were just a few of the English monarchs captured on the battlefield; the French suffered this indignity, too, with Louis IX, John II and Francis I all seized in battle. In the latter stages of the Hundred Years War, French kings ordered their forces to avoid battlefield engagements with the English; the English, on the other hand, especially under Edward III, actively sought combat, as they were likely to be victorious. But for all their battlefield defeats, the French still won the war, as sieges and campaigns proved more decisive over the long run.

But avoidance was usually preferred because all could be lost on one throw of the dice: William of Poitiers claims that in 1066 Duke William of Normandy conquered England in a day because of Hastings; Richard III lost the crown at Bosworth in 1485; and the decimation of crusading manpower at the Horns of Hattin in 1187 decided the fate of the kingdom of Jerusalem. When a commander actively sought battle, he usually did so because the situation was such that it offered better prospects than avoidance, as proved to be the case at Castelnaudary and Muret. These were the exceptions in the Albigensian Crusade; like the vast majority of other medieval conflicts, the long grind of campaigns and sieges constituted the reality of combat more than the explosive drama of a brief battle.

Two major elements of battle are missing from the main accounts of Muret: footsoldiers and archers. We are familiar with the notion of effective infantry and archers from the great English victories of the Hundred Years War: Crécy, Poitiers, Agincourt. From this has arisen a myth of the late medieval military revolution: roughly stated, prior to this, cavalry dominated the battlefield, the other troops offering little more than ancillary support. Muret might seem to support this inaccurate view. But here Montfort not only needed his infantry to defend the town; he also needed to move quickly across the plain to fall on the enemy with as much surprise as possible. There would have been infantry pikemen in the southerner ranks, lined up as a barrier against charging cavalry. Such a disposition could be remarkably effective long before the Hundred Years War. At Gisors in 1188, English infantry beat off two French cavalry charges: the French ‘launched into the press’; the infantry stood firm and ‘did not evade this onslaught’ as they ‘received them with their pikes’.135