“Sometimes goodbye is a second chance”

—“Second Chance”

Shinedown

Imagine the furor I would have created had I signed with the Colorado Avalanche in 2006. That was a possibility after the Red Wings bought out my contract that summer.

I don’t think the Detroit fan base would have ever forgiven me had I chosen that option.

It would be like President Obama saying he was going to join the Republican Party or Ford Motor Company announcing that it was moving its headquarters to Japan.

But after the Red Wings announced that they were buying out Derian Hatcher, Ray Whitney, and me, the Avalanche were the first team to show interest in signing me. The team’s director of player personnel was Brad Smith, an ex–Red Wings player who was nicknamed “Motor City Smitty.” In that era, he scouted many games at Joe Louis Arena and he told me he had an appreciation of what I offered to a team.

Although I had hoped to spend my entire career as a Red Wing, I wasn’t angry with Detroit general manager Ken Holland’s decision to buy out my contract because I knew it was a logical move.

The Red Wings had a payroll of about $77 million in 2003–04, and then owners locked out players because they wanted a salary cap. We lost the 2004–05 season, and then we ended up with a $39 million salary cap. The Red Wings had to trim their payroll, and they had a six-day window to buy out players without having the buyout count against the cap.

In buying out Hatcher ($4.66 million), Whitney ($2.66 million), and me ($1.7 million), they cut almost $9 million.

If I were the Detroit general manager, I would have made the same decision that Holland made. If I were making less than $1 million, I might have been mad that the Red Wings didn’t work harder to keep me. But by that time in my career, I was making real money.

Plus, I was 33 and I had been injured for a large chunk of the previous season. When you’re that age, you’re always vulnerable.

Even though the moves made perfect sense, it was still difficult for Holland to tell me that I was no longer going to be a Red Wing. He and I had been together in the organization for 11 years. He was my boss, but to me he seemed more like a father figure. Because it’s my personality to do whatever I can to help the team, I tried to make the conversation as easy as possible.

I told him at the meeting that there were no hard feelings, and that I understood that the team was forced into this move by factors that were out of Holland’s control.

As I look back on that situation, I blame myself for putting myself in the position of being one of the cuts when the team needed to trim.

At that point in my career, the Red Wings were not overly pleased with some of my off-ice habits. They knew that I had a drug issue, and that my marriage was breaking up. They probably worried that a divorce would mean even less stability in my life and maybe wilder behavior.

Also, Holland and some of my teammates had asked me to be less involved with my band, Grinder. The argument was that it had become a distraction, and that it had taken my focus away from hockey.

Holland wanted me not to have any gigs during the season, and he wasn’t happy when he showed up at training camp and discovered we were playing in Traverse City to take advantage of all of the Red Wings fans that were in town.

The point is that perhaps the Red Wings would have been more creative in trying to find a way to keep me if I had been a model citizen.

I wasn’t shocked by the buyout, because there was media speculation about the situation long before it happened. I was surprised and pleased when I received a call from Calgary general manager and coach Darryl Sutter because I had always respected the Sutter family approach to hockey.

He offered me $800,000 a season on a two-year deal, and frankly I would have gone there for less.

I thought Sutter would be the perfect coach for me, and that turned out to be the case. He never gave me any specific instructions on how to play, other than to say I should play the way I always had.

Based on how Sutter treated me, I believed he respected what I had to offer as a player. That’s all I ever ask from my coach. I just want to feel like I’m contributing. He had some similarities to Scotty Bowman. Both men were tough coaches, but they’d adjusted their styles through the years to accommodate the changes in the game and the players.

Sutter put me on a line with Stephane Yelle and Marcus Nilson and we stayed together most of the season.

Maybe we weren’t the second coming of the Grind Line, but we had good chemistry. We were effective. Yelle was called “Sandbox” because he did all the dirty work. I knew Yelle from playing against him when he was in Colorado, but I gained even more for him as a teammate. He sweats the small stuff, and he was always willing to do the little things that make a team successful.

It was a good group in Calgary, and it helped me that recovering alcoholic Chris Simon was on the team. At the team gatherings, I wasn’t the only one not drinking. Simon understood my struggles maybe even better than I did. We went to meetings together, and he had been fighting alcoholism even longer than I had.

I’m sure some of my teammates knew bits and pieces of my battles with substance abuse, but no one really asked me about it in-depth. Simon knew details, but he was not the kind of guy who was going to talk to anyone else about it. Chris was a quality guy.

The two of us had some fun acting as chauffeurs for goalie Miikka Kiprusoff, who rates as one of the funniest teammates I’ve ever had.

He smoked and drank Scotch, and I swear the more he drank the better his English got. If you could understand him perfectly, you knew he probably had had too much to drink.

Kiprusoff reminded me a bit of Chris Osgood because we would be at a gathering and he wouldn’t say much for a long period of time and then suddenly he would make a random off-the-wall comment that would leave the room in stitches.

On the ice, he was like Dominik Hasek in that he didn’t like to get beat—even in practice.

What I remember most about the Flames is what a fun-loving group we had that season.

The boys always enjoyed watching Mixed Martial Arts (MMA) on TV, usually at Rhett Warrener’s or Jarome Iginla’s homes. They especially loved Chuck Liddell’s fights.

Those nights always seemed like a frat party. Once everyone had been into the sauce for a while, the shirts would come off and the wrestling would commence.

Iginla always squared off against his best buddy, Chuck Kobasew, and it would always end up getting out of hand. Some of us would have to step in and serve as peacemakers.

It was like the battles that Draper and I used to have, except we didn’t have an audience. It was like the Roman circus when Iginla and Kobasew put on a match for their teammates’ enjoyment.

We actually banned MMA watching during the playoffs because we were afraid that someone might get hurt.

By the way, Warrener is one of the best teammates I ever had in my career. He instantly reminded me of Chris Chelios because of the way he treated everyone. Those two players treated all of their teammates the same, whether they had been with them for 30 days or 10 seasons. Warrener took care of everyone on the Flames, in the same manner that Chelios took care of everyone on the Red Wings. If you needed a hook-up for anything in Calgary, Warrener was the man who could get it done.

One of my favorite memories of my Calgary days was the Bad Christmas Sweater party Warrener hosted. I saw some of the gaudiest Christmas sweaters known to man. I recall Yelle won the hideous sweater contest wearing one with a butt-ugly reindeer on the front. Honestly, it looked like that reindeer was going to leap off his chest.

Warrener had gone all out for this party. He had a nice place with a beautiful open kitchen. He had his Christmas tree all lit up and beautifully trimmed in the true holiday spirit.

Everyone brought their wives or girlfriends, and everyone was dolled up for the occasion. It had all of the ingredients of a classy affair. However, the Calgary boys did like to drink at their parties. That meant it was inevitable that a food fight was going to break out at this holiday gathering.

This wasn’t two kids at a breakfast table hurling Cheerios at one another. This was a holiday spread food fight, complete with turkey, mashed potatoes, stuffing, cranberries, and corn, among other items.

The second ammunition dump included a table of cupcakes in the corner that also came with a chocolate fondue fountain.

Also available were bottles and bottles of red wine, quality wine that could stain carpeting, with no remorse or remedy.

Trying to figure out who started this food fight is like trying to figure out who really caused World War I. Fingers were pointed at many different parties. Clearly, entangling alliances played a major role. Once the first shot was fired, emotion simply took over.

My recollection is that Warrener, because he owned the house, was comfortable enough to throw the first cupcake at defenseman Robyn Regehr.

But I may be saying that because Warrener and Regehr were usually involved at the start of all the horseplay that got out of hand. As soon as Regehr was hit, it became a night of mass destruction.

It was the mother of all food fights. I remember ducking a mashed potato bomb and then getting drilled in the chest with a chocolate-frosted missile. Turkey explosions were landing everywhere. No one was safe. Players. Wives. Girlfriends. There were 30 people involved in the skirmish. Casualties were high.

At one point, Warrener fell into the Christmas tree and knocked it over, probably because he was trying to avoid a barrage of salad raining down on him.

When a cease-fire was called 15 minutes after the war began, Warrener’s house looked like it had been under a mortar attack. People were trying to scrape chocolate out of their eyes, and sweep the cranberry sauce off their dresses and shirts. Women were pulling turkey remnants out of blouses. Carpets were stained blood-red. Clothing was ruined. Many people had vegetables and/or stuffing in their hair. You couldn’t put your hand down without it landing in a goo that used to be dinner. Everyone was sticky. Everyone was drunk.

It may have been the best holiday party I ever attended. No one is ever going to forget that gathering, particularly Warrener, who said it took him three days to clean up the mess.

But knowing Warrener, if he had it to over again, he would have done it exactly the same way.

This was a tight team. We called Regehr “Reggie.” He was the king of the iPod, and he and I spent many nights watching rock shows at the Back Alley. I liked the young guys on that team as well. Chuck Kobasew, Matt Lombardi, and Byron Ritchie, in particular, were respectful kids. What I remember most about the Flames is that we held at least one team party per month.

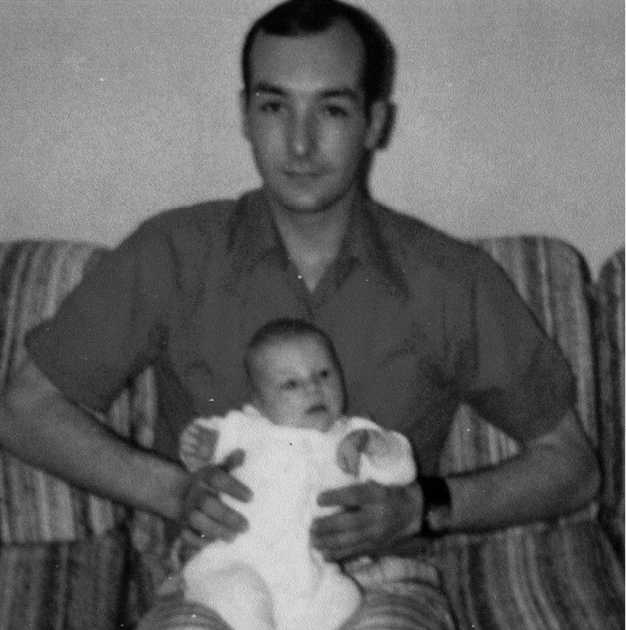

The move to Calgary was also good for me because it allowed me to become more acquainted with my biological father, Doug Francottie, who lived in Edmonton. I’d reached out to him in 1996, but I wasn’t ready then to stay in touch with him. I believed I was ready to meet him in 2004, mostly because I needed answers to the question of why I was the way I was.

I was 32 when I met my father for the first time. It was on a Red Wings road trip to Edmonton. We talked for six hours. He said the reason he never had any contact with me was because he was in the Witness Protection Program. While he was working as a cop in British Columbia he took down an Asian mob boss and the department decided he needed to enter the Program to protect his family. It reminded me of the story I told women to get rid of them after I grew bored with an affair.

“It’s the best thing for you,” I would say. “It’s not your fault. It’s my fault. I’m leaving you to protect you from me.”

My biological father’s explanation sounded as hollow as my speeches must have sounded to the women I bedded.

Doug Francottie said once it was determined that the threat to his life was over, he came out of hiding, although he still remains a bit secretive even today.

In the two years I was in Calgary, Doug came down often to hang out with me.

He told me he had been following my hockey career for years. He’d even seen me play NHL games live before he actually met me.

I don’t know whether I believed every word he told me, but getting to know him was important to me because it helped me understand why I am the way I am. It took me reconnecting with him to realize that what was going on inside of him was what was going on inside of me. I’ve recently heard Bishop T.D. Jakes say, “The problems were generational, not situational.” And that’s exactly correct. It is painfully clear that he and I have some of the same wiring.

He’s also an alcoholic. His drink is Bacardi and Diet Coke. We spent a lot of time together in casinos. My father was constantly being chased by bill collectors. He seems to have many of the same issues that I have, leading me to the conclusion that I inherited some, if not all, of my demons from him.

We kept in contact for a while, but I eventually realized that I was initiating most of our meetings. He also left out pertinent details to his life story, such as the fact that he had a second family. We fell out of contact. He was in Windsor two years ago, and tried to reach out to me. I attempted to call him back, but by then his number was disconnected.

When Bob Probert died, I arrived in Windsor at the funeral to find my father standing in the parking lot. He said he knew I would be there, and he wanted to see me. We talked briefly, and I haven’t seen him since. I don’t know where he is today.

When I played with Calgary that first season, Simon and I shared the tough-guy duties. He had eight fights and I had seven, plus one more in the postseason against Anaheim’s Sean O’Donnell.

Sutter played me about 11 minutes per game during the regular season, and I ended up with seven goals and six assists for 13 points. He seemed happy with the way I was playing. I never had a single issue with Sutter.

In the playoffs, I ended up scoring two goals in our seven-game-series loss to the Anaheim Ducks. One of my goals came in overtime in the opening game.

In a 1–1 game, teammate Kristian Huselius, stationed behind the net, spotted me and fed me a perfect pass as I cruised into the slot. I one-timed the puck past goalie Ilya Bryzgalov for the victory. What made that moment such an amazing coincidence was the fact that almost a decade before I had been on the ice with the young teenage puck magician Huselius at the Tomas Storm hockey camp.

That’s the beauty of NHL playoff hockey. On a team full of guys with more offensive skill than me, the role player was the guy who produced the game-winning goal.

In my exit interview it was clear that the Flames were pleased with me and were looking forward to having me back the following season. I looked forward to coming back because I enjoyed playing for Sutter. He coached the game the way I liked to play the game.

When Sutter coached the Los Angeles Kings to the Stanley Cup championship in 2012, I certainly wasn’t surprised. I could tell that the Kings were buying into the Sutter program. Guys want to play hard for Sutter. They want to win for him because he treats them like men.

I was optimistic about my future with the Flames. At the time, what I didn’t realize was that Sutter would not be back behind the Flames bench. I also could not have predicted that my struggles with substance abuse would hit an all-time low.

When the Flames announced on July 12 that Sutter was stepping down as coach but would remain as general manager, I had no idea how it would change my status in Calgary.

To be honest, I didn’t care what was happening in Calgary because I was in the midst of a drunken stupor.