“Talking ’bout girls, talking ’bout trucks, runnin’ them red dirt roads, out kicking up dust”

—“Boys ’Round Here”

Blake Shelton

When I played for the Adirondack Red Wings in 1992–93, we were the toughest team in professional hockey. I’m not talking about minor league hockey. I’m talking about pro hockey, including the NHL.

Eight players on that team boasted 100 or more penalty minutes. I put up 278 penalty minutes that season with only one misconduct penalty. My recollection is that I collected 45 fighting majors. Kirk Tomlinson had 224 minutes. Bob Boughner was at 190 minutes. Jim Cummins came in at 179. Dennis Vial was at 177. The late Marc Potvin had 109. Micah Aivazoff, one of our top goal scorers, even had 100. Serge Anglehart was probably the toughest guy on the team, but he didn’t play much that season because of a bad shoulder. These guys all had NHL-caliber toughness.

Unquestionably, we tried to intimidate our opponents.

I vividly recall Tomlinson and I having Providence tough-guy Darren Banks cornered against the boards and arguing about who was going to fight him.

“I’m fighting him,” I told Tomlinson

“Back off kid, I got him,” Tomlinson replied.

Meanwhile, Banks is just standing there hoping one of us will fight him so he can go on with his life.

Before Tomlinson reacts, I jump in and start fighting Banks. Tomlinson was furious at me that I took his fight. We would argue all of the time on the bench about which opponent each would get to fight. There were not enough willing combatants to go around. It was a wild season.

My plan that season was to follow the same game plan Coach Drumm had given me when I played Junior B hockey in Peterborough. I had to establish myself to make people respect me. I fought every time I was given the opportunity. But I always felt as if opponents took it easy on me that season because they didn’t want to face a murderer’s row of tough guys if they hurt me.

Tomlinson would say, “Don’t hurt the kid because if you do you know what will come next.”

The art of fighting in pro hockey isn’t as simple as the average fan thinks it is. There are unwritten rules that have to be followed. I learned that in my first NHL training camp when I beat up a guy in a rookie league game against the Toronto Maple Leafs.

On my way to the penalty box, I was high-fiving guys and celebrating like I had just won the championship belt.

Later that night, Red Wings assistant general manager Doug MacLean came up to me and said, “The way you acted after that fight is unacceptable. This is the NHL, not the World Wrestling Federation. A member of the Detroit Red Wings doesn’t act the way you acted.”

The message was received loud and clear. When it came to fighting, I wanted to do it the right way.

My willingness to drop the gloves against anyone, at any time, quickly made me a fan favorite. Fans seemed to like the fact that I chewed gum when I played. When I was done with a fight, I would blow a bubble just to show everyone I was fine. Fans sent me buckets upon buckets of Bazooka bubble gum. My dressing room stall was stacked three feet high with bubble gum.

Even though I was in the minors, I would have to say that season was among the most enjoyable of my hockey career. We had an incredible amount of fun that season. In addition to being tough, we could play. We were a skillful group. The season before, in 1991–92, Adirondack had captured the American Hockey League championship with Barry Melrose behind the bench.

The Los Angeles Kings had hired Melrose to be their head coach in the summer of 1992, and the Red Wings had brought in Newell Brown to be Adrirondack’s new coach. He was only 30 years old, meaning he wasn’t much older than some of the guys on the team. One of our goalies, Allan Bester, was 28. Ken Quinney and Bobby Dollas were two of our better players, and they were both 27.

The Adirondack team in 1992–93 was a mixture of veterans who thought they should be playing in the NHL, and bunch of younger guys such as Chris Osgood, Slava Kozlov, and me, who hoped to be there soon.

We had impressive offensive firepower on this team. Chris Tancill was like the Brett Hull of minor league hockey. He scored 59 goals in 68 games that season, and might have had an opportunity to take down Stefan Lebeau’s league record of 70 goals had he not been recalled to the Red Wings for five weeks in the middle of the season.

One thing I will always remember about Tancill was that he was the speediest dresser I’ve ever seen. No one could don gear for a practice or game quicker than Tancill. He could dress cup to jersey in under two minutes. I know that because I actually timed him once because I was so fascinated by his dressing skill. He could walk in the door of the dressing room, and be out on the ice for practice in three minutes. It was one of the most amazing talents I ever witnessed in hockey.

Gary Shuchuk was another player who seemed like he should be in the show. He was a hard-nosed player, and he could dangle with the puck. Quinney and Mica Aivazoff were also 30-goal guys.

It was like an old-school team because all of the tougher players understood that our job was to make sure no one bothered our scorers. It was our job to make sure our scorers had plenty of room on the ice, and we did that job very well.

What made my Adirondack experience more enjoyable was the fact that the veterans considered it their job to make me a better hockey player. They wanted me to move forward in my career. The older tough guys made me their gofer to be sure, but they also sat me down and passed down the fighting wisdom they acquired. They taught me how to pick my spots to fight, and schooled me on the importance of timing my fights to help my team.

On some teams, the competition for playing time was a cutthroat endeavor, everyone looking out for themselves. But none of my Adirondack teammates were like that. They took me under their wing and said, “Hey, kid, we are going to help you get to the next level. You just need to pay attention to us.”

About 15 of us lived in the same apartment complex. I was living with Boughner and Serge Anglehart. Chris Osgood and Mike Casselman lived together. Bobby Dollas and his wife lived in the same complex, as did Cummins and Vial.

It was a close-knit team. There wasn’t much night life in Glen Falls, New York. So we made our own entertainment. We spent a lot of time together as a team. My keen interest in golf started because most of the players on my first pro teams were golfers. That spring, we played every chance we had.

At that time, I was just starting to break 100 and the older players, particularly Tomlinson, were established golfers. As I recall, Tomlinson was actually a Canadian pro. He gave me my first set of clubs.

Of course, the guys golfed for money and they weren’t handing out handicap strokes to me. I either had to improve my game in a hurry or keep paying out money to these guys. I chose to improve.

One of the gambling games they played involved tying a red-and-white snake made out of tape onto the bag of the last guy to three-putt. Whomever had that snake on his bag at the end of round had to pay. I owned that fucking snake way too often. But it made me a better golfer. By the end of season I had probably shaved 10 or 12 strokes off my game. By the end of my first season, I could shoot in the 80s.

What I remember most about my first pro season is that we had many barbecues, drinking sessions, and plenty of adventures.

The Red Wings realized quickly that I liked to party too much, and general manager Jim Devellano suggested to my girlfriend, Cheryl, that she may want to consider moving to Glen Falls around Christmas that season. The Red Wings’ hope was that she would tone down my act.

We moved into an apartment that was right above Osgood and Casselman’s. What I remember most about that arrangement was that I was constantly downstairs playing Sega Genesis video games with Osgood and Casselman.

When we played that NHL game, I was always Chicago because the Jeremy Roenick player was God in that Sega game. Casselman was Washington and Ozzie was always Vancouver. We wrapped tape around a Gatorade jug and treated it like the Stanley Cup of video hockey. We wrote the winners of our tournaments on our Gatorade Cup. We would often play all night.

Sometimes, Cheryl would have to get out of bed and stomp on the floor to signal for me to come home.

When that would happen, Ozzie would say, “Your old lady is calling you.”

It’s the kind of shit you say when you are 20 and don’t have a fucking care in the world. It was an awesome life.

That season was one adventure after another. Glens Falls is located in the mountains, and Gord Kruppke and Avisoff lived at the top of the mountain. We said they lived at the top of the world because it was a lengthy trek, on windy mountain roads, to get there.

But we would take advantage of that in the winter by attaching inner tubes to the back of Anglehart’s truck. You would sit in the inner tubes and ski behind the truck as Serge flew around those mountain roads. There was nothing better than tubing at the top of the world. We always had the truck filled with players and girlfriends on our tubing expeditions.

One night I remember Stew Malgunas, Mike Sillinger, and I were on the tubes when the truck took a turn too sharply. We flipped over, and found ourselves sliding down the embankment. We tumbled about 20 feet until we were stopped by a well-placed tree. We weren’t hurt, just pissed that our teammates had left us behind.

The guys in the truck didn’t even initially realize we were missing, and they kept driving down the mountain.

“Now we have walk up this hill,” Sillinger said.

“No, we don’t,” I said, and pulled a bottle of Southern Comfort out of my coat.

The three of us sat under the tree and drank most of the bottle while our buddies searched for us. We had some fun at their expense. We would yell to them, and then hide as they got closer. They had no idea whether we were injured or fucking with them.

Another time, I was on the tubes alongside Anglehart’s girlfriend. She was about to slam into a garage on her tube and I made a dive off mine to knock her out of harm’s way. The problem was that I ended up slamming into the garage and suffering a nasty hip pointer. I was a bruised mess.

When you are a professional athlete, particularly a first-year pro trying to prove you belong, the last thing you want to do is tell your coach you have been injured while tubing down mountain roads.

But my teammates had my back. The plan was that some of us would show up early for practice and go out on the ice. When Coach Brown showed up, everyone was going to say I had been hurt by crashing into the boards. My injuries were consistent with that kind of accident. The plan worked, I missed four games, and Brown had no idea what really happened.

My life as a pro hockey player was just as I hoped it would be when I was signed by the Red Wings.

I was 20 when I proposed to Cheryl. Most 20-year-old hockey players are not in a hurry to get married. Pro athletes at that age are far more interested in the promise of tomorrow than who might be by their side today. Her parents were like parents to me in Belleville; marrying Cheryl seemed like the right thing to do.

* * *

The 1992–93 Adirondack team deserved a better fate that season.

On January 29, 1993, the Red Wings traded Shuchuk, Potvin, and Jimmy Carson to Los Angeles in the deal that brought Paul Coffey to Detroit.

At the time that Shuchuk was dealt to Los Angeles he was leading the AHL with 77 points in 47 games. He had 24 goals and 53 assists. The Kings wanted Shuchuk because Melrose knew him well from the previous season in Adirondack when Shuchuk helped him win the title.

After Tancill was called up and Shuchuk was moved, we went into an offensive funk, highlighted by a stretch when we went 79 consecutive power play opportunities without scoring a goal.

At 14.69 percent efficiency, our power play ranked last in the AHL that season. But even for a team with a bad power play, Bentley University mathematics professor Richard Cleary says a slump of that magnitude would only happen once every 1,000 seasons.

For a team with an average power play, the chances of that happening would be once every 150,000 years.

Despite our power play woes, we still ended up as one of the top-scoring teams in the AHL that season. We finished with a 36–35–9 record, good enough for second in the Northern Division. The AHL was a highly competitive league in that era, evidenced by the fact that the coaches that season included names such as Barry Trotz, Robbie Ftorek, Marc Crawford, Mike O’Connell, Mike Eaves, John Van Boxmeer, and Doug Carpenter.

We expected to make some noise in the postseason. Tancill had been returned to Adirondack, and Sillinger had been sent down late in the season. He was a skilled offensive player. Kozlov, meanwhile, was improving daily.

We swept the Capital District Islanders in the first round, outscoring them 17–6.

The other good news was that Springfield had upset Northern Division–winner Providence in their first-round series. We were clearly the favorite in our second-round series. The Indians had a record of 25–41–14 during the season, and we had posted an 8–3–1 record against them in the regular season.

But the series against Springfield did not go as planned. We split two games in Glens Falls, and then split two games in Springfield. Tancill missed Game 4 because of the birth of his daughter, but he came back in Game 5 to record a hat trick, leading us to a 7–2 win. Finally, it seemed as if we were in control of the series. Again, that was not the case.

Before Game 6, Bester told coaches he couldn’t play because he was having a marital issue. Bester’s troubles were not the kind that gain you much sympathy in a professional dressing room.

Osgood stepped in and played well, but we lost a heartbreaking 2–1 game. Springfield’s No. 1 goalie, George Maneluk, was injured during that game, but Corrie D’Alessio stepped in and played well to post his first win in about five months. With six seconds to go in that game, Sillinger believed he had scored the tying goal, but the referee said the puck never crossed the line. Sillinger insisted the puck had crossed the line, and D’Alessio had slyly pulled it back. Playoff hockey can also produce strange twists.

In Game 7, Maneluk and Bester were back in the net, and Bester didn’t have a great night. We outshot Springfield 63–37 and lost 6–5 in overtime.

Kruppke scored with 1:15 left in regulation to give us a 5–4 lead, and we thought we were moving on in the playoffs. Then Springfield pulled Maneluk for a sixth attacker and Denis Chalifoux beat Bester with 51 seconds remaining.

We had outshot Springfield 17–5 in the third period. Maneluk, who never made it to the NHL, made 17 more saves in overtime. Then, Paul Cyr, a former NHL player on his way down, scored on a breakaway at 16:56 to win it for Springfield.

That series was probably one of the most frustrating stretches of my career. It didn’t help that I couldn’t buy a goal in that series.

It was not as if we didn’t have our top guys going. Our top three forwards, Tancill, Aivazoff, and Quinney, had 39 points in 11 games. Sillinger was dominant with five goals and 13 assists for 18 points in 11 games. Dollas had 11 points in 11 games. He might have been the top defenseman in minor league hockey that season. In the regular season, he had seven goals and 36 assists for 43 points in 64 games. He also boasted a plus-minus of plus-54.

Even with the loss of Shuchuk, we should have had enough jam left to make a longer run in the playoffs. It was a very disappointing finish for all involved. We just couldn’t keep the puck out of our net.

The only solace I took from the season was the fact that I had shown enough to prove that I belonged in the NHL.

I went into the next training camp believing I would make the team. The Red Wings had made significant changes after losing to the Toronto Maple Leafs on Nikolai Borschevsky’s overtime goal in a Game 7. Bryan Murray stayed as Detroit’s general manager, but he lost his place behind the bench. Scotty Bowman was brought in to get the job done.

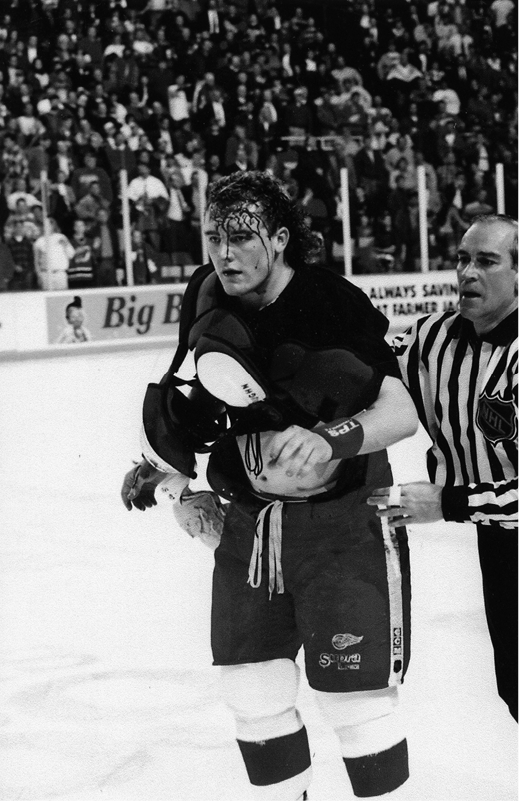

Right away, it seemed as if Scotty liked what I could offer. In my mind, I made the team because of a fight I had at Chicago Stadium in a preseason game. It was against Cam Russell, and it’s available on YouTube for those who care to see it first-hand.

The play started with Tony Horacek and Keith Primeau mixing it up in the corner, and Russell came flying in to help. I grabbed him and hit him a couple of times and put him down on the ice.

“You fucking jumped me,” Russell bitched at me as I held him down.

“You want to go again? I’ll go again,” I said. “Let’s go to center ice.”

That’s the way we did it in junior hockey, so I thought that was the way it should be done in the NHL.

We only made it as far as the blue line and then we started throwing punches. It was a great fight. It was like Rocky Balboa and Apollo Creed trading punches. He hit me, cutting me for five stitches, and then I buckled him twice with punches. He went down, and the crowd was going nuts. It was an unbelievable feeling to hear all of the fans cheering and yelling. That’s what it must have been like when gladiators fought centuries ago. It was quite an adrenaline rush.

In the old Chicago Stadium, you had to walk down stairs in your skates to get to the dressing room. As I made the descent, fans were pouring drinks on me and showering me with popcorn and empty cups. I loved it, and I remember thinking that Bowman had to know that night that I was a tough competitor.

When I entered the dressing room, Bob Probert, who wasn’t dressed for that game, was working out on the stationary bike. He looked up at me, and said, “Kid, you are fucking crazy.”