CHAPTER

42

I couldn’t sleep for three days. On the fourth morning, along with so many of Daniel’s friends, colleagues and undergraduates, I attended his funeral service at Trinity Chapel. I somehow survived that ordeal and the rest of the week, thanks not least to Daphne’s organizing everything so calmly and efficiently. Cathy was unable to attend the service as they were still detaining her for observation at Addenbrooke’s Hospital.

I stood next to Becky as the choir sang out “Fast Falls the Eventide.” My mind drifted as I tried to reconstruct the events of the past three days and make some sort of sense of them. After Daphne had told me that Daniel had taken his own life—whoever selected her to break the news understood the meaning of the word “compassion”—I immediately drove up to Cambridge, having begged her not to tell Becky anything until I knew more of what had actually happened myself. By the time I arrived at Trinity Great Court some two hours later, Daniel’s body had already been removed, and they had taken Cathy off to Addenbrooke’s, where she was not surprisingly still in a state of shock. The police inspector in charge of the case couldn’t have been more considerate. Later, I visited the morgue and identified the body, thanking God that at least Becky hadn’t experienced that ice-cold room as the last place she was alone with her son.

“Lord, with me abide…”

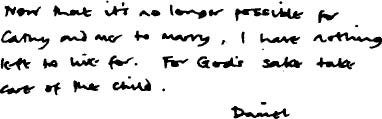

I told the police that I could think of no reason why Daniel should want to take his own life—that in fact he had just become engaged and I had never known him happier. The inspector then showed me the suicide note: a sheet of foolscap containing a single handwritten paragraph.

“They generally write one, you know,” he said.

I didn’t know.

I began to read Daniel’s neat academic hand:

I must have repeated those twenty-eight words to myself over a hundred times and still I couldn’t make any sense out of them. A week later the doctor confirmed in his report to the coroner that Cathy was not pregnant and had certainly not suffered a miscarriage. I returned to those words again and again. Was I missing some subtle inference, or was his final message something I could never hope to comprehend fully?

“When other helpers fail…”

A forensic expert later discovered some writing paper in the grate, but it had been burned to a cinder and the black, brittle remains yielded no clue. Then they showed me an envelope that the police believed the charred letter must have been sent in and asked if I could identify the writing. I studied the stiff, thin upright hand that had written the words “Dr. Daniel Trumper” in purple ink.

“No,” I lied. The letter had been hand-delivered, the detective told me, some time earlier that afternoon by a man with a brown moustache and a tweed coat. This was all the undergraduate who caught sight of him could remember, except that he seemed to know his way around.

I asked myself what that evil old lady could possibly have written to Daniel that would have caused him to take his own life; I felt sure the discovery that Guy Trentham was his father would not have been sufficient for such a drastic cause of action—especially as I knew that he and Mrs. Trentham had already met and come to an agreement some three years before.

The police found one other letter on Daniel’s desk. It was from the Provost of King’s College, London, formally offering him a chair in mathematics.

“And comforts flee…”

After I had left the mortuary I drove on to Addenbrooke’s Hospital, where they allowed me to spend some time at Cathy’s bedside. Although her eyes were open, they betrayed no recognition of me: for nearly an hour she simply stared blankly up at the ceiling while I stood there. When I realized there was nothing I could usefully do I left quietly. The senior psychiatrist, Dr. Stephen Atkins, came bustling out of his office and asked if I could spare him a moment.

The dapper little man in a beautifully tailored suit and large bow tie explained that Cathy was suffering from psychogenic amnesia, sometimes known as hysterical amnesia, and that it could be some time before he was able to assess what her rate of recovery might be. I thanked him and added that I would keep in constant touch. I then drove slowly back to London.

“Help of the helpless, O abide with me…”

Daphne was waiting for me in my office and made no comment about the lateness of the hour. I tried to thank her for such endless kindness, but explained that I had to be the one who broke the news to Becky. God knows how I carried out that responsibility without mentioning the purple envelope with its telltale handwriting, but I did. Had I told Becky the full story I think she would have gone round to Chester Square that night and killed the woman there and then with her bare hands—I might even have assisted her.

They buried him among his own kind. The college chaplain, who must have carried out this particular duty so many times in the past, stopped to compose himself on three separate occasions.

“In life, in death, O Lord, abide with me…”

Becky and I visited Addenbrooke’s together every day that week, but Dr. Atkins only confirmed that Cathy’s condition remained unchanged; she had not yet spoken. Nevertheless, just the thought of her lying there alone needing our love gave us something else to worry about other than ourselves.

When we arrived back in London late on Friday afternoon Arthur Selwyn was pacing up and down outside my office.

“Someone’s broken into Cathy’s flat, the lock’s been forced,” he said even before I had a chance to speak.

“But what could a thief possibly hope to find?”

“The police can’t fathom that out either. Nothing seems to have been disturbed.”

To the puzzle of what Mrs. Trentham could have written to Daniel I added the mystery of what she could possibly want that belonged to Cathy. After checking over the little room myself I was none the wiser.

Becky and I continued to travel up and down to Cambridge every other day, and then midway through the third week Cathy finally spoke, haltingly to start with, then in bursts while grasping my hand. Then suddenly, without warning, she would go silent again. Sometimes she would rub her forefinger against her thumb just below her chin.

This puzzled even Dr. Atkins.

Dr. Atkins had since then, however, been able to hold extensive conversations with Cathy on several occasions and had even started playing word games to probe her memory. It was his opinion that she had blotted out all recollection of anything connected with Daniel Trumper or with her early life in Australia. It was not uncommon in such cases, he assured us, and even gave the particular state of mind a fine Greek name.

“Should I try and get in touch with her tutor at the University of Melbourne? Or even talk to the staff of the Melrose Hotel—and see if they can throw any light on the problem?”

“No,” he said, straightening his spotted bow tie. “Don’t push her too hard and be prepared for that part of her mind to take some considerable time to recover.”

I nodded my agreement.

“Back off” seemed to be Dr. Atkins’ favorite expression. “And never forget your wife will be suffering the same trauma.”

Seven weeks later they allowed us to take Cathy back to Eaton Square where Becky had prepared a room for her. I had already transferred all Cathy’s possessions from the little flat, still unsure if anything was missing following the break-in.

Becky had stored all Cathy’s clothes neatly away in the wardrobe and drawers while trying to make the room look as lived in as possible. Some time before, I had taken her watercolor of the Cam from above Daniel’s desk and rehung it on the staircase between the Courbet and the Sisley. Yet when Cathy first walked up those stairs on the way to her new room, she passed her own painting without the slightest sign of recognition.

I inquired once again of Dr. Atkins if perhaps we should now write to the University of Melbourne and try to find out something about Cathy’s past, but he still counseled against such a move, saying that she must be the one who came forward with any information, and then only when she felt able to do so, not as the result of any pressure from outside.

“But how long do you imagine it might be before her memory is fully restored?”

“Anything from fourteen days to fourteen years, from my experience.”

I remember returning to Cathy’s room that night, sitting on the end of her bed and holding her hand. I noticed with pleasure that a little color had returned to her cheeks. She smiled and asked me for the first time how the “great barrow” was rumbling along.

“We’ve declared record profits,” I told her. “But far more important, everyone wants to see you back at Number 1.”

She thought about this for some time. Then quite simply she said, “I wish you were my father.”

In February 1951 Nigel Trentham joined the board of Trumper’s. He took his place next to Paul Merrick, to whom he gave a thin smile. I couldn’t bring myself to look directly at him. He was a few years younger than me but I vainly considered no one round that table would have thought so.

The board meanwhile approved the expenditure of a further half a million pounds “to fill the gap,” as Becky referred to the half-acre that had for ten years lain empty in the middle of Chelsea Terrace. “So at last Trumper’s can all be housed under one roof,” I declared. Trentham made no comment. My fellow directors also agreed to an allocation of one hundred thousand pounds to rebuild the Whitechapel Boys’ Club, which was to be renamed the “Dan Salmon Center.” I noticed Trentham whispered something in Merrick’s ear.

In the event, inflation, strikes and escalating builders’ costs caused the final bill for Trumper’s to be nearer seven hundred and thirty thousand pounds than the estimated half million. One outcome of this was to make it necessary for the company to offer a further rights issue in order to cover the extra expense. Another was that the building of the boys’ club had to be postponed.

The rights issue was once again heavily oversubscribed, which was flattering for me personally, though I feared Mrs. Trentham might be a major buyer of any new stock: I had no way of proving it. This dilution of my equity meant that I had to watch my personal holding in the company fall below forty percent for the first time.

It was a long summer and as each day passed Cathy became a little stronger and Becky a little more communicative. Finally the doctor agreed that Cathy could return to Number 1. She went back to work the following Monday and Becky said it was almost as if she had never been away—except that no one ever mentioned Daniel’s name in her presence.

One evening, it must have been about a month later, I returned home from the office to find Cathy pacing up and down the hall. My immediate thoughts were that she must be agonizing over the past. I could not have been more wrong.

“You’ve got your staffing policy all wrong,” she said as I closed the door behind me.

“I beg your pardon, young lady?” I had not even been given enough time to shed my topcoat.

“It’s all wrong,” she repeated. “The Americans are saving thousands of dollars in their stores with time and motion studies while Trumper’s is behaving as if they’re still roaming around on the ark.”

“Captive audience on the ark,” I reminded her.

“Until it stopped raining,” she replied. “Charlie, you must realize that the company could be saving at least eighty thousand a year on wages alone. I haven’t been idle these last few weeks. In fact, I’ve put together a report to prove my point.” She thrust a cardboard box into my arms and marched out of the room.

For over an hour after dinner I rummaged into the box and read through Cathy’s preliminary findings. She had spotted an overmanning situation that we had all missed and characteristically explained in great detail how the situation could be dealt with without offending the unions.

Over breakfast the following morning Cathy continued to explain her findings to me as if I had never been to bed. “Are you still listening, Chairman?” she demanded. She always called me “chairman” when she was wanted to make a point. A ploy I felt sure she had picked up from Daphne.

“You’re all talk,” I told her, which caused even Becky to glance over the top of her paper.

“Do you want me to prove I’m right?” Cathy asked.

“Be my guest.”

From that day on, whenever I carried out my morning rounds, I would invariably come across Cathy working on a different floor, questioning, watching or simply taking copious notes, often with a stopwatch in her other hand. I never asked her what she was up to and if she ever caught my eye all she would say was, “Good day, Chairman.”

At weekends I could hear Cathy typing away in her room for hour after hour. Then, without warning, one morning at breakfast I discovered a thick file waiting for me in the place where I had hoped to find an egg, two rashers of bacon and The Sunday Times.

That afternoon I began reading through what Cathy had prepared for me. By the early evening I had come to the conclusion that the board must implement most of her recommendations without further delay.

I knew exactly what I wanted to do next but felt it needed Dr. Atkins’ blessing. I phoned Addenbrooke’s that evening and the ward sister kindly entrusted me with his home number. We spent over an hour on the phone. He had no fears for Cathy’s future, he assured me, especially since she’d begun to remember little incidents from her past and was now even willing to talk about Daniel.

When I came down to breakfast the following morning I found Cathy sitting at the table waiting for me. She didn’t say a word as I munched through my toast and marmalade pretending to be engrossed in the Financial Times.

“All right, I give in,” she said.

“Better not,” I warned her, without looking up from my paper. “Because you’re item number seven on the agenda for next month’s board meeting.”

“But who’s going to present my case?” asked Cathy, sounding anxious.

“Not me, that’s for sure,” I replied. “And I can’t think of anyone else who’d be willing to do so.”

For the next fortnight whenever I retired to bed I became aware when passing Cathy’s room that the typing had stopped. I was so filled with curiosity that once I even peered through the half-open bedroom door. Cathy stood facing a mirror, by her side was a large white board resting on an easel. The board was covered in a mass of colored pins and dotted arrows.

“Go away,” she said, without even turning round. I realized there was nothing for it but to wait until the board was due to meet.

Dr. Atkins had warned me that the ordeal of having to present her case in public might turn out to be too much for the girl and I was to get her home if she began to show any signs of stress. “Be sure you don’t push her too far,” were his final words.

“I won’t let that happen,” I promised him.

That Thursday morning the board members were all seated in their places round the table by three minutes to ten. The meeting began on a quiet note, with apologies for absence, followed by the acceptance of the minutes of the last meeting. We somehow still managed to keep Cathy waiting for over an hour, because when we came to item number three on the agenda—a rubber stamp decision to renew the company’s insurance policy with the Prudential—Nigel Trentham used the opportunity simply as an excuse to irritate me—hoping, I suspected, that I would eventually lose my temper. I might have done, if he hadn’t so obviously wanted me to.

“I think the time has come for a change, Mr. Chairman,” he said. “I suggest we transfer our business to Legal and General.”

I stared down the left-hand side of the table to focus on the man whose very presence always brought back memories of Guy Trentham and what he might have looked like in late middle age. The younger brother wore a smart well-tailored double-breasted suit that successfully disguised his weight problem. However, there was nothing that could disguise the double chin or balding pate.

“I must point out to the board,” I began, “that Trumper’s has been with the Prudential for over thirty years. And what is more, they have never let the company down in the past. Just as important, Legal and General are highly unlikely to be able to offer more favorable terms.”

“But they’re in possession of two percent of the company’s stock,” Trentham pointed out.

“The Pru still have five percent,” I reminded my fellow directors, aware that once again Trentham hadn’t done his homework. The argument might have been lobbed backwards and forwards for hours like a Drobny-Fraser tennis match had Daphne not intervened and called for a vote.

Although Trentham lost by seven to three, the altercation served to remind everyone round that table what his long-term purpose must be. For the past eighteen months Trentham had, with the help of his mother’s money, been building up his shareholding in the company to a position I estimated to be around fourteen percent. This would have been controllable had I not been painfully aware that the Hardcastle Trust also held a further seventeen percent of our stock—stock which had originally been intended for Daniel but which would on the death of Mrs. Trentham pass automatically to Sir Raymond’s next of kin. Although Nigel Trentham lost the vote, he showed no sign of distress as he rearranged his papers, casting an aside to Paul Merrick who was seated on his left. He obviously felt confident that time was on his side.

“Item seven,” I said, and leaning over to Jessica I asked if she would invite Miss Ross to join us. When Cathy entered the room every man around that table stood. Even Trentham half rose from his place.

Cathy placed two boards on the easel that had already been set up for her, one full of charts, the other covered in statistics. She turned to face us. I greeted her with a warm smile.

“Good morning, ladies and gentlemen,” she said. She paused and checked her notes. “I should like to begin by…”

She may have started somewhat hesitantly, but she soon got into her stride as she explained, point by point, why the company’s staffing policy was outdated and the steps we should take to rectify the situation as quickly as possible. These included early retirement for men of sixty and women of fifty-five; the leasing of shelf space, even whole floor sections, to recognized brand names, which would produce a guaranteed cash flow without financial risk to Trumper’s, as each lessee would be responsible for supplying its own staff; and a larger percentage discount on merchandise for any firms who were hoping to place orders with us for the first time. The presentation took Cathy about forty minutes, and when she concluded it was several moments before anyone round the table spoke.

If her initial presentation was good, her handling of the questions that followed was even better. She dealt with all the banking problems Tim Newman and Paul Merrick could throw at her, as well as the trade union anxieties Arthur Selwyn raised. As for Nigel Trentham, she handled him with a calm efficiency that I was only too painfully aware I could never equal. When Cathy left the boardroom an hour later all the men rose again except Trentham, who stared down at the report in front of him.

As I walked up the path that evening Cathy was on the doorstep waiting to greet me.

“Well?”

“Well?”

“Don’t tease, Charlie,” she scolded.

“You were appointed to be our new personnel director,” I told her, grinning. For a moment even she was speechless.

“Now you’ve opened this can of worms, young lady,” I added as I walked past her, “the board rather expects you to sort the problem out.”

Cathy was so obviously thrilled by my news that I felt for the first time perhaps Daniel’s tragic death might be behind us. I phoned Dr. Atkins that evening to tell him not only how Cathy had fared but that, as a result of her presentation, she had been elected to the board. However, what I didn’t tell either of them was that I had been forced to agree to another of Trentham’s nominations to the board in order to ensure that her appointment went through without a vote being called for.

From the day Cathy arrived at the boardroom table it was clear for all to see that she was a serious contender to succeed me as chairman and no longer simply a bright girl from Becky’s fold. However, I was well aware that Cathy’s advancement could only be achieved while Trentham remained unable to gain control of fifty-one percent of Trumper’s shares. I also realized that the only way he could hope to do that was by making a public bid for the company, which I accepted could well become possible once he got his hands on the money held by Hardcastle Trust. For the first time in my life I wanted Mrs. Trentham to live long enough to allow me to build the company to such a position of strength that even the Trust money would prove inadequate for Nigel Trentham to mount a successful takeover bid.

On 2 June 1953 Queen Elizabeth was crowned, four days after two men from different parts of the Commonwealth conquered Everest. Winston Churchill best summed it up when he said: “Those who have read the history of the first Elizabethan era must surely look forward with anticipation to participating in the second.”

Cathy took up the Prime Minister’s challenge and threw all her energy into the personnel project the board had entrusted her with, and was able to show a saving of forty-nine thousand pounds in wages during 1953 and a further twenty-one thousand pounds in the first half of 1954. By the end of that fiscal year I felt she knew more about the running of Trumper’s at staff level than anyone around that table, myself included.

During 1955 overseas sales began to fall sharply, and as Cathy no longer seemed to be extended and I was keen for her to gain experience of other departments I asked her to sort out the problems of our international department.

She took on her new position with the same enthusiasm with which she tackled everything, but during the next two years began to clash with Nigel Trentham over a number of issues, including a policy to return the difference to any customer who could prove he had paid less for a standard item when shopping at one of our rivals. Trentham argued that Trumper’s customers were not interested in some imagined difference in price that could be compared with a lesser known store, but only in quality and service, to which Cathy replied, “It isn’t the customers’ responsibility to be concerned with the balance sheet, it’s the board’s on behalf of our shareholders.”

On another occasion Trentham came near to accusing Cathy of being a communist when she suggested a “workers’ share participation scheme” which she felt would create company loyalty that only the Japanese had fully understood—a country, she explained, where it was not uncommon for a company to retain ninety-eight percent of its staff from womb to tomb. Even I was unsure about this particular idea, but Becky warned me in private that I was beginning to sound like a “fuddy duddy,” which I assumed was some modern term not to be taken as a compliment.

When Legal and General failed to get our insurance business they sold their two percent holding outright to Nigel Trentham. From that moment I became even more anxious that he might eventually get his hands on enough stock to take over the company. He also proposed another nomination to the board which, thanks to Paul Merrick’s seconding, was accepted.

“I should have secured that land thirty-five years ago for a mere four thousand pounds,” I told Becky.

“As you have reminded us so often in the past, and what’s worse,” Becky reminded me, “is that Mrs. Trentham is now more dangerous to us dead than alive.”

Trumper’s took the arrival of Elvis Presley, Teddy boys, stilettos and teenagers all in its stride. “The customers may have changed, but our standards must not be allowed to,” I continually reminded the board.

In 1960 the company declared a seven-hundred-and-fifty-seven-thousand-pound net profit, a fourteen percent return on capital, and a year later went on to top this achievement by being granted a Royal Warrant from the monarch. I instructed that the House of Windsor’s coat of arms should be hung above the main entrance to remind the public that the Queen shopped at the barrow on a regular basis.

I couldn’t pretend that I had ever seen Her Majesty carrying one of our familiar blue bags with its silver motif of a barrow, or spotted her as she traveled up and down the escalators during peak hours, but we still received regular telephone calls from the Palace when they found themselves running short of supplies: which only proved yet again my old granpa’s theory that an apple is an apple whoever bites it.

The highlight of 1961 for me was when Becky finally opened the Dan Salmon Centre in Whitechapel Road—another building that had run considerably over cost. However, I didn’t regret one penny of the expenditure—despite Merrick’s niggling criticism—as I watched the next generation of East End boys and girls swimming, boxing, weightlifting and playing squash, a game I just couldn’t get the hang of.

Whenever I went to see West Ham play soccer on a Saturday afternoon, I could always drop into the new club on my way home, and watch the African, West Indian and Asian children—the new East Enders—battle against each other just as determinedly as we had done against the Irish and Eastern European immigrants.

“The old order changeth, yielding place to new; And God fulfils himself in many ways, Lest one good custom should corrupt the world.” Tennyson’s words, chiseled in the stone on the archway above the center, brought my mind back to Mrs. Trentham, who was never far from my thoughts, especially while her three representatives sat around the boardroom table eager to carry out her bidding. Nigel, who now resided at Chester Square, seemed happy to wait for everything to fall into place before he marshaled his troops ready for the attack.

I continued to pray that Mrs. Trentham would live to a grand old age as I still needed more time to prepare some blocking process to ensure that her son could never take over the company.

It was Daphne who first warned me that Mrs. Trentham had taken to her bed and was receiving regular visits from the family GP. Nigel Trentham still managed to keep a smile on his face during those months of waiting.

Without warning on 7 March 1962 Mrs. Trentham, aged eighty-eight, died.

“Peacefully in her sleep,” Daphne informed me.