“Empire” today is a loaded and largely pejorative term. Yet it was not always so. Before the War of Independence began in 1775, the Founding Fathers had no quarrel with the concept of imperialism itself. George Washington fought against the French Empire to protect and expand the British one, while Benjamin Franklin campaigned for colonial union to advance imperial ambitions on both sides of the Atlantic.

It might be assumed that the war changed everything, but it did not. As soon as the ink was dry on the peace treaty in 1783 that ended hostilities, a new imperial project started—this time controlled by the United States rather than the British. Washington spoke warmly of “a rising empire,” while Thomas Jefferson coined the phrase “empire for liberty.” Alexander Hamilton described his country as “the embryo of a great empire.” John Adams, father and son, as well as James Madison, were all equally enthusiastic.

European empires had been based on territorial expansion, and the British one was no exception. The thirteen colonies in what would become the United States had spread westward from the coast by displacing the indigenous1 peoples through purchase, treaty, and war. As the flow of new immigrants accelerated, the need for further territory increased. Land speculation by the colonial elites became the surest and quickest way to build a fortune.

All the Founding Fathers participated in the process, and several were major shareholders in the land companies set up under colonialism to expand the frontiers. George Washington inherited from his brother Lawrence a substantial share of the Ohio Company that had been founded in 1747 to speculate in land south and north of the Ohio River. Benjamin Franklin was convinced that the “Ohio Country” was absolutely essential for the future prosperity of the colonies on the grounds that “our people . . . cannot much more increase in number” east of the Allegheny Mountains.2

The Treaty of Paris in 1763, which ended hostilities between Britain and France, seemed to meet the needs of British imperial expansion. France ceded her claims on the mainland of North America to Spain and Great Britain, including in the latter case the land east of the Mississippi River, and a vast area west of the Appalachian Mountains now appeared to be open to British settlers. However, the French had not consulted their Native American allies, who had no intention of vacating land they owned and occupied.

The result was Pontiac’s War, which dragged Great Britain into a serious conflict that it was in no position to fight after so many years of hostilities. This was one of the reasons for the famous Royal Proclamation of 1763 drawing a line from Canada to Florida along the ridge of the Appalachian Mountains west of which no white settlers were permitted. It brought peace of a kind, but at a stroke of the pen George III had rendered worthless the assets of the land companies between the Mississippi River and the mountains.

This was an intolerable affront to the colonial elites, for whom territorial expansion now formed part of their DNA. All forms of pressure, including subterfuge, were adopted to undermine the impact of the Proclamation Line. The Illinois Company, with Franklin as a shareholder, pleaded with the colonial authorities for a grant of sixty-three million acres between the Illinois and Mississippi Rivers. A new company—variously called the Grand Ohio, the Walpole, or the Vandalia—was formed to petition the British government in London for an even bigger grant.

These efforts were only partially successful. By the Treaty of Fort Stanwix in 1768 Virginia was able to (re)claim some of the land south of the Ohio River; a few settlers “leased” land from Native American tribes, and this appeared not to breach the ban on white ownership. However, the land to the north of the river remained firmly out of bounds, and George III added insult to injury in 1774 by allocating this land (between the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers) to the Canadian province of Quebec.

Thus, on the eve of the War of Independence, settler expansion had been blocked north of the Ohio River and restricted to the south. Reversing this situation was one of the undeclared aims of the rebels. Not surprisingly, therefore, most of the Native American tribes eventually sided with the British since it was their land that was at stake.

Many of the battles were fought west of the Proclamation Line, and the Native American tribes—unlike the British—were not defeated. They remained in possession of most of the lands they owned before the war, but they were not present at the peace negotiations that led to the Treaty of Paris in 1783. Thus, it came as a complete shock to them to discover that the British had ceded the land east of the Mississippi River to the US commissioners.

This was not the first or the last time that the British would betray their Native American allies, but it was still a shocking act of perfidy. Many of the tribes had at first been reluctant to join with the British in the war and some had even sided with the rebels. Yet the majority had eventually been induced to take part on the assumption that this was the surest way to keep their lands.

The conclusion of the War of Independence was therefore a potential disaster for the Native American tribes. At the same time it was not at all clear what “rights” the United States had acquired from the departing British in the territory to the east of the Mississippi since the Native Americans had not signed the treaty. What was clear, however, was the commitment to territorial expansion by the new nation even if that meant armed confrontation.

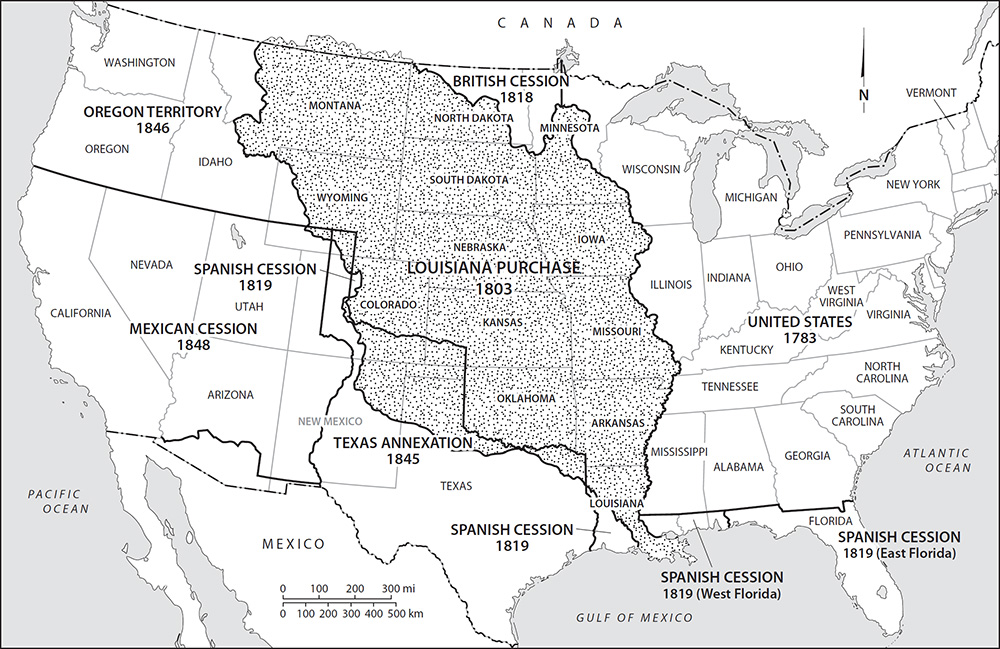

The stage was therefore set for the first chapter in the formation of the American empire: continental expansion. Within seventy years of independence, the federal government had consolidated its hold on all the acreage east of the Mississippi, and the white subjects of the territories carved out of the newly acquired lands were gradually learning how to become citizens of the Union. West of the river, the federal government had acquired title to vast swaths of land previously claimed by the empires of France, Great Britain, Russia, and Spain, forming these into territories. Their inhabitants in most cases, however, would have to spend decades as colonial subjects of the new US empire before becoming citizens.

When the War of Independence ended, the vast majority of the US population were living on the eastern side of the mountains. Indeed, most were living within fifty miles of the coast. The first census in 1790 enumerated a free population of 3,231,533. This number, of course, excluded the slaves (nearly 700,000), but it also excluded the Native Americans.

No serious attempt was made to estimate their number, but recent scholarship suggests a figure in 1800 between 600,000 and 1,000,000 for North America as a whole.3 Few of these lived east of the mountains, where the white population was concentrated. Thus, despite the spread of European diseases and decades of conflict, there was still a significant Indian population in the territories of interest to the federal government.

The Native Americans lived in villages and small towns where, in general, farming was carried out by the women and hunting by the men. We cannot be sure how many lived in the land between the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers (the old Northwestern territories), but in the late eighteenth century it was certainly more than the white settlers. Indeed, the 1790 census could not give a figure for the settlers in this region, and even in 1800 the number was tiny.4

The new republic knew that a claim to these lands based on cession by Great Britain amounted to little, but the government did believe that it had acquired title by conquest. By defeating the British, with whom so many of the tribes had been allied, it claimed all the Indian land (Box 1.1). However, before anything could be done about it, the federal government had to extinguish the land claims of the individual states. This was no simple matter, but the agreement of Virginia in 1784 to relinquish its claims to the land north of the Ohio River paved the way for the famous Northwest Ordinance of 1787.

This act marked the formal birth of the US empire and set a precedent for territorial expansion across the continent. It created a vast region (the Northwest Territory—see Map 1) in lands where the majority of the population were Native Americans and where the entry of slaves would not be permitted. The president was empowered to appoint a governor, a secretary, and three judges with sovereign powers subject only to presidential veto. Once the white male settler population exceeded five thousand, provision was made for elections to a House of Representatives, while a Legislative Council would be made up of those chosen by the president from a list presented by the House. The territory would then be entitled to send a nonvoting delegate to the US Congress.

This was a system of colonial rule that would have been very familiar to the British, Dutch, or French. The indigenous people had no rights, the white population had limited representation, and the colonial agents exercised enormous powers.5 There was, however, one difference in the United States, and that was the assumption that a territory would eventually become a state of the Union. Yet this could take decades to achieve, and in the meantime the territory was ruled as a de facto colony.

That the federal government had colonies in North America may sound strange to modern ears, but it did not seem strange to contemporaries. Arthur St. Clair, the first governor of the Northwest Territory, wrote in 1795 that the land he ruled was a “dependent colony” whose settlers “ceased to be citizens of the United States and became their subjects.” Nor did this colonial condition either surprise or worry many of the white inhabitants. In Wisconsin, for example, which was carved out of the Northwest Territory many years later, “large majorities were actively hostile to statehood long after the territory passed the sixty thousand population threshold that qualified it for admission under the Ordinance.”6

Map 1. Northwest Territory

The American government, believing it had acquired the land by conquest, summoned tribal leaders after the War of Independence ended and imposed treaties that obliged the signatories to relinquish territory. The majority of Native American tribal leaders in the Northwest Territory, however, did not accept that they had lost the right to their lands as a result of the British defeat. The victory the government claimed by virtue of conquest was, therefore, fraught with problems. A shift in policy—from entitlement by conquest to ownership by purchase—was therefore needed and was signaled by the Northwest Ordinance itself. This stated, “The utmost good faith shall always be observed towards the Indians, their lands and property shall never be taken from them without their consent, and in their property, rights and liberty, they shall never be invaded or disturbed, unless in just and lawful wars authorized by Congress.”7

BOX 1.1

ABEL BUELL (1742–1822)

Cartography and empire building have always gone together, and the American empire is no exception. The first map of the United States to be done by a US citizen was published in 1784, by a Connecticut engraver named Abel Buell. A skilled draftsman, Buell had been convicted before the War of Independence of forging paper currency and was punished by branding (“C” for “counterfeiter” on his forehead), the loss of an ear, and a jail sentence. He then turned his talents to more respectable pursuits.

His map, only seven copies of which survive, was drawn when most of the former colonies had yet to cede their land claims west of the Proclamation Line to the federal government. It therefore shows the western boundaries of Connecticut, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia as the Mississippi River.

Buell’s map also shows the location of many of the Native American tribes, including some west of the Mississippi River. The western portion of Georgia, for example, is marked as “Chactaw [sic] Land,” while the territory west of Lake Michigan is shown as “Winnebago Land.”

Most interesting of all is the physical description Buell gives to the land east of the Mississippi River. The land south of Lake Michigan and north of the Wabash River, for example, is described as “level rich and well watered. The road between these forts [St. Joseph and Miami] runs through many fine meadows. There are several small lakes and plenty of fish fowls and wild beasts.”

Buell’s map, done in four parts, was controversial because it presented the boundaries of each state west of the Allegheny Mountains as if they were agreed (they were not). It also gave the impression that most of this land was unoccupied by Native Americans, which was not true. And its description of the land, aimed at settlers and land companies, was worthy of a real estate developer.

What, however, would happen if the Indians did not want to sell or, even worse, wanted to sell to some agency other than the federal government? This was a possibility the executive was not prepared to contemplate since the US government could not function without the land. It was needed to pay off the veterans, to meet the demands of settlers, and as a source of revenue (only the federal government was empowered to acquire land from the Native Americans, which could then be sold at a profit). Thus, it was no surprise that Congress was soon authorizing “just and lawful” wars against the Native Americans.

At first, these wars did not go well for the new republic. US forces lost a major battle in 1790 against a combination of Native American tribes. The following year St. Clair himself suffered a major defeat when his army was cut to pieces and 940 of his 1,400 soldiers were killed or wounded. However, the tide began to turn in 1794 when US forces under General Anthony Wayne somewhat fortuitously won the Battle of Fallen Timbers.8

US losses were in fact greater than those of the Native Americans at Fallen Timbers. However, some tribal leaders now believed it was impossible to hold the boundary between themselves and the United States at the Ohio River. In the Treaty of Greenville, signed in 1795, they therefore agreed on a new line of separation. This still left most of the Northwest Territory in the hands of Native American tribes, but it was the “foot in the door” that the federal government needed, and the new boundary—straight lines on a map north of the river—was easy for unscrupulous settlers to cross illegally.

It was not long after this that the first administrative hurdle of five thousand white male settlers had been met and the Northwest Territory moved to the second stage of territorial government in 1799. The following year the territory was divided with the creation of Indiana Territory. Despite being far larger than modern Indiana, its white settler population in 1800 was a mere 5,641, and most of these were of French descent. However, the rest of the Northwest Territory was rapidly filling up and by 1802 was in a position to petition for statehood. Ohio State, whose boundaries included some land not included in the Treaty of Greenville, then came into being in 1803 (Map 1).

Ohio State, now being in the Union, was no longer a colony. However, the remainder of the Northwest Territory (Indiana Territory) was and would remain so for some time. Indeed, its first governor (William Henry Harrison) was a classic example of a colonial ruler with a strong interest in land speculation as well. One of his biographers wrote, “Not a shadow of representative institutions existed in the territory, for all the offices were appointive and the laws were made by the governor and the judges.”9

Harrison ruled the territory from Vincennes on the Wabash River, but it was too vast even for a man of his imperial ambitions. By 1805 Michigan Territory had been carved out of Indiana, and Illinois Territory would follow in 1809. Each had governors in the same mold as Harrison, and all would follow the new policy of trying to persuade the Native Americans to sell their land and move elsewhere.

This required “inducements,” and no one understood this better than Thomas Jefferson, who became president in 1801. Writing to Harrison in 1803, he stated,

When they [Indians] withdraw themselves to the culture of a small piece of land, they will perceive how useless to them are their extensive forests, and will be willing to pare them off from time to time in exchange for necessaries for their farms and families. . . . To promote this . . . we shall push our trading houses, and be glad to see the good and influential individuals among them run into debt, because we observe that when these debts get beyond what the individuals can pay, they become willing to lop them off by a cession of lands.10

Jefferson was promoting an extreme interpretation of the “civilization” policy, adopted a decade earlier by President George Washington (1789–97) and his secretary of war, Henry Knox. If implemented strictly, it would have at least created the possibility of a society in which whites and Native Americans lived side by side as agriculturalists. It was, however, undermined by Jefferson himself as a consequence of the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 (see Section 1.3).

Suddenly, with the Louisiana Purchase, the federal government found itself responsible for vast tracts of territory to the west of the Mississippi River. Native American lands to the east of the river could now be exchanged for land on the other side. The policy of “civilization,” slow and expensive to implement, could be replaced by “removal”—a much quicker and cheaper alternative.

Harrison and the other governors experimented with all these policies. However, the one Harrison found most effective was to sign treaties with those tribal leaders that could be bribed. At the Treaty of Fort Wayne in 1809 he obtained the signatures of a handful of leaders to a swath of territory that encompassed land belonging to, among others, the Shawnees. One of their leaders, Tecumseh, denounced those that had signed, and he traveled to Vincennes to demand that Harrison reject the treaty.

Harrison would not back down and Tecumseh, whose brother Tenskwatawa (“the Prophet”) was already raising pan-Indian consciousness across the old Northwest, started to recruit a mobile force that transcended tribal barriers. War was inevitable, but victory for the federal government was not. Indeed, were it not for the poor decision making of the Prophet, Tecumseh might well have won. Harrison’s forces were small and the technological superiority of his army relatively minor. As it was, the Battle of Tippecanoe in 1811 cemented Harrison’s military reputation and provided the rallying cry for his presidential campaign three decades later.11

Tecumseh was not present at Tippecanoe, and the following year the United States launched an ill-advised war against Great Britain to conquer the Canadian provinces and add them to the US empire. This gave the pan-Indian forces under Tecumseh another chance to push back US territorial expansion in the old Northwestern territories. Supported by the British under General Isaac Brock, Tecumseh’s warriors won several battles. However, Brock was killed and his successor, General Henry Proctor, abandoned Tecumseh before the Battle of the Thames, where the great Shawnee leader was killed in 1813.

When the war ended in 1814, Native American resistance in the Northwest Territory was almost over. Betrayed (again) by the British, and without their charismatic leader, Native American rivalries and disputes returned. Territorial governors took full advantage to push for land cessions through treaty, while some Native American leaders exchanged their land for territory west of the Mississippi. There was now nothing to stop Indiana and Illinois entering the Union as states in 1816 and 1818, respectively (Map 1).

That left Michigan Territory, whose governor from 1813 to 1831 was Lewis Cass. Like Harrison, Cass was sympathetic to the idea of reversing the ban on slavery included in the Northwest Ordinance and ruled his territory like an old-fashioned colonial governor in the British Empire. During his period in office, the white settler population rapidly increased (it had been a mere 4,762 in 1810) and part of the territory joined the Union in 1837 as Michigan State (Map 1).

What now remained was Wisconsin Territory, carved out of Michigan in 1836. It would remain outside the Union until 1848, by which time it had effectively been ruled as a colony for sixty-one years, starting with the appointment of St. Clair in 1787. Even this period of long colonial rule was surpassed by the eastern part of modern Minnesota (Map 1), which lay within the old Northwest Territory and which finally achieved statehood in 1858, after seventy-one years.12

The old Northwestern territories gave the federal government its first experience of colonial rule. And it was a long one, starting in 1787 and ending in 1858. It had all the ingredients we have come to expect from colonies: subject peoples (in the form of both Native Americans and whites); recalcitrant and sometimes rebellious settlers; a colonial superstructure based on governors, secretaries, and judges; limited representative government; and imperial veto powers. All it lacked was a slave labor force, which was only to be found south of the Ohio River. It is to this area that we now turn.

The claim of the young republic on the territory south of the Ohio River (the old Southwestern territories) was based on the 1783 Treaty of Paris. A few years later the United States government, relying on a “right of conquest” claim, signed the Treaties of Hopewell.13 This attempted to establish a new boundary between the Native American tribes and the settlers. And southern states, whose claims ran all the way to the Mississippi River, also signed treaties designed to extend their authority over land occupied by the Indians.14

These preliminary efforts to extend the empire into the old Southwestern territories were unsuccessful. The Indians did not consider that they had been defeated, had not signed the Treaty of Paris, and were much more numerous south of the Ohio River than north of it. It is true that the Proclamation Line had been breached by the Treaty of Fort Stanwix in 1768,15 giving the settlers access to lands in western Virginia beyond the Appalachian Mountains, and whites were to be found in significant numbers in western North Carolina. However, this still left most of the region in the possession of Native Americans.

When the federal government took office under the new US Constitution in 1789, it faced three major obstacles that prevented it extending the empire west to the lower Mississippi River and south to the Gulf of Mexico. First, Spain—the colonial power in both Louisiana and Florida—claimed the land between the Chattahoochee and Mississippi Rivers up to latitude 32° 28´ north, whereas the United States claimed the same land as far south as 31° north (Map 2).16 Second, the southern states—especially Georgia—proved unwilling to cede their land claims west of the mountains. Third, the Indians were larger in number, better organized, and more diplomatically astute in the old Southwestern territories than in the Northwest Territory.

It would take the federal government half a century to overcome all these obstacles. Limited progress toward removing the first obstacle, however, was made fairly quickly. As a result of the Treaty of San Lorenzo in 1795, also known as Pinckney’s Treaty, Spain recognized the border between western Florida and the United States as latitude 31° north (Map 2). Although Spain also gave the United States freedom to trade on the Mississippi and the right of deposit at New Orleans, this still left her in control of all of the Gulf of Mexico, and it would take many years before she was finally dislodged (see Section 1.4).

The second obstacle—states’ western land claims—was particularly difficult to overcome. Yet it was essential for the success of the imperial exercise, since the Constitution made clear that only the federal government could negotiate and sign treaties with the Native Americans. Thus, breaking the power of the Indians and forcing land cessions required establishing federal authority over the states.

The federal government had no need to persuade Virginia to relinquish its land claims to the south of the Ohio River in Kentucky. This area had filled rapidly with settlers and their slaves after the Treaty of Fort Stanwix, the Indians had been driven out, and there was a sufficiently large white population to meet the requirements for statehood. Kentucky, after a brief period in the Southwest Territory (see below), therefore became a state in 1792.

South of Kentucky, the land was claimed by North Carolina. The state first ceded its claim in 1784, but this had led to the bizarre incident of the Franklinites, when a group of settlers unsuccessfully petitioned Congress to recognize “Franklin State” in eastern Tennessee. North Carolina then rescinded its land cession, only to cede it again in 1789. This paved the way for the federal government to create the Southwest Territory in 1790, although its southern boundary only extended to the 35th parallel where the Georgian land claims began.17

The Southwest Territory soon met the conditions for statehood and joined the Union as the State of Tennessee in 1796, although it still had a large Indian population in the center (they would be driven out in the next few years). The federal government then turned its attention to the area further south. The concessions by Spain in 1795 allowed the United States to proceed toward the first stage of territorial government by creating Mississippi Territory in 1798. This, however, only filled the space ceded by Spain and did not extend north to the southern border of Tennessee, as this land—as far south as 32° 28´—was still claimed by Georgia (Map 2).

Georgia not only claimed the land but also the right to sign treaties with the Indians. This was in open defiance of the Constitution, but the federal government failed to take action. However, the Georgians overreached themselves when selling land in what would become federal territory. The Yazoo scandals (there were two of them) were so outrageous that the Georgian government eventually agreed to cede the western lands to the federal government in 1802.18 Two years later Mississippi Territory was extended north to the borders of Tennessee (Map 2).

The white population of the new territory was very small, despite the fact that it incorporated Alabama, and included French, Spanish, and British settlers as well as Americans. The loyalty of these imperial subjects concerned the governors. One of the first was William Claiborne (1801–3), who wrote to the secretary of state,

Map 2. Mississippi Territory

That a decided Majority of the People of this Territory, are Americans in principles and attachments, I do verily believe. But (to my great Mortification) there are persons here, on whose Judgments and hearts, former habits have made unfortunate Impressions; favorable to Monarchy, and inimical to every Government that recognizes the Rights of Man.—Several families from Kentucky, Tennessee and this Territory, have lately emigrated to the Province of Louisiana, (and it is feared that this example may be followed by others); The facility with which lands may be acquired under the Spanish authority, and the prevalence of an opinion that the subjects of Spain are exempt from taxation, are probably the principal Inducements to this abandonment of their Country.19

The principal obstacle facing all governors, however, was the opposition of the Indians to further land cessions. The Native Americans of the old Southwestern territories had in the main sided with the British in the War of Independence, but they had not been defeated. They knew, however, that their survival depended on tribal cohesion and accommodation wherever possible with the settlers.

The federal government considered the Indian tribes as sovereign and referred to them as “nations.” In the case of the tribes in the Northwest Territory this was a convenient legal fiction serving the interests of both sides.20 However, some of the tribes in the old Southwestern territories did succeed in constructing nations. This process was taken furthest by the Cherokees, who were the closest to the main centers of settler populations and whose institutions would come to mirror those in the federal government itself.

The US administration, despite the opposition of the states (especially Georgia), at first favored a policy of “civilization” with respect to these nations. This policy was in fact well received by many Indians, as the traditional economy of the tribes was being wiped out by the loss of hunting grounds and the reduction in the population of deer and other wild animals. Indian men not only took up plows and other farming instruments but some also acquired slaves and moved into cash crops such as tobacco and cotton. As early as 1802, Governor Claiborne could write optimistically to the secretary of war, “The progress of civilization among the Cherokees, Chickasaws, and upper Creeks, authorize a hope that the Indians within our Limits may ultimately be rescued from a State of Barbarism, & to contribute to the attainment of an object so interesting to humanity, would be to me a source of great gratification.—The Choctaws are indeed, generally involved in Savage life, but even among them, a Spirit of Industry has recently appeared; and the cultivation of the Soil is becoming the principal employment of several families.”21

The pressure from the settlers was relentless, however, and they received the full support of the southern states. Inevitably, this led to new treaties with the federal government, in which the Native Americans were forced to cede land in the hope of protecting at least part of their domains. The Choctaws, for example, ceded 2.6 million acres in the 1801 Treaty of Fort Adams, 3.85 million in the 1803 Treaty of Hoe Buckintoopa, and 4.1 million in the 1805 Treaty of Mount Dexter. It was the same for the other tribes.

Resentment steadily increased, and Tecumseh’s efforts to build a Pan-Indian alliance against the United States were welcomed by many in the south. When the War of 1812 against Great Britain was launched, it provided the excuse to mount attacks. A faction of the Creeks, the Red Sticks,22 captured Fort Mims near the mouth of the Alabama River the following year and inflicted major casualties on US forces.

Not all Creeks were in favor of war, and neither were the Cherokees. General Andrew Jackson was therefore able to include some Native Americans in his volunteer force that crushed the Red Sticks at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend in 1814. A few months later, at the Treaty of Fort Jackson, the Creek nation was forced to cede twenty-two million acres (one-third of their territory). This land included some of the richest agricultural land in the south, and those who had fought with Jackson suffered just as much as those who fought against.

BOX 1.2

WAS “REMOVAL” GENOCIDE?

No reasonable person can deny that the forced removal of the Native Americans from the east to the west of the Mississippi River was ethnic cleansing, which today is a crime under international law. More controversially, was forced removal also genocide? This is an even more serious crime under international law today.

The Convention on Genocide was adopted by the United Nations in 1948, and Article 2 defines genocide to include

any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

(a) Killing members of the group;

(b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

(c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

(d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

(e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

Indian removal would seem to be covered by at least part of Article 2, especially 2(b). Indeed, the US government—clearly worried about the implications of Article 2—felt obliged to enter an “understanding” to the convention stating: “(1) That the term ‘intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial, or religious group as such’ appearing in article II means the specific intent to destroy, in whole or in substantial part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group as such by the acts specified in article II. (2) That the term ‘mental harm’ in article II (b) means permanent impairment of mental faculties through drugs, torture or similar techniques.”

If Indian removal was genocide, then its principal architect was Andrew Jackson. During his presidency (1829–37), 100 million acres of Indian land were added to the public domain and hardly any Indians remained east of the Mississippi River. Jackson also defied the Supreme Court, the only US president to do so, when he refused to act after Georgia had been found in breach of federal law.

The end of the war coincided with a big increase in cotton prices and a huge influx of new settlers. This allowed the federal government in 1817 to split Mississippi Territory, creating Alabama Territory in the east and admitting Mississippi as a state. Following Spain’s decision in 1819 to transfer her remaining possessions in Florida to the United States (see Section 1.4 in this chapter), Alabama itself became a state. All of the old Southwestern territories were now in the Union.

This might have been an opportunity for a display of magnanimity by the federal government toward the Indians, many of whom were still on the east of the Mississippi River. The tribes had all signed land treaties with the United States, giving them ownership and occupation of a much reduced area and within which commercial agriculture was increasingly being practiced. A significant number had been converted to Christianity by the missionaries living among them, and literacy was gaining ground.23 The Cherokees, where a system of writing in their own language had been developed, even adopted a constitution in 1827 modeled on that of the United States.

Far from welcoming these changes, the southern states and their settlers were appalled. They did not want to live side by side with Indians, however civilized. What they wanted was the rich agricultural land, the timber in the forests, and, following the discovery of gold in Cherokee territory in 1828, access to the minerals. And if the Indians would not move, they made it clear that the consequences would be severe. This was emphasized by the Alabama Legislature in 1829, where it was said, “It is believed that when they shall discover that the state of Alabama is determined upon her sovereign rights, and when they see and feel some palpable act of legislation under the authority of the state, then their veneration for their own law and customs will induce them speedily to remove.”24

Under pressure from the southern states, therefore, the policy of the federal government in the old Southwestern territories shifted from “civilization” to removal (Box 1.2). Indeed, it went further since the ambition now was to crush the pretensions to statehood of the Indian nations. The aggression was led by Andrew Jackson long before he became president, but even James Monroe—once a firm believer in “civilization”—argued in his last presidential address in 1824 that the Indians must be induced to move west. And the campaign received a boost from the Supreme Court in 1823 when Chief Justice John Marshall referred to the status of Native Americans as “dependent domestic nations” rather than as sovereign states.25

When Andrew Jackson became president in 1829, he wasted no time in putting the new policy in place. The Indian Removal Act was passed by Congress in 1830 and in the same year the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek deprived the Choctaws of their remaining land in the east. The Creeks, one of whose leaders (William McIntosh) had already signed a fraudulent treaty in 1825 giving away much of their land, were the next to go. In 1832 the Treaty of Pontotoc would lead to the removal of the Chickasaws.26

The Cherokees were the last to be forced out, naively trusting US federal law to protect them both against states and settlers as well as from fraudulent treaties. It was all in vain. Some, led by the Ridge family, moved voluntarily, but the majority under John Ross stayed until they were evicted by force. The horrific tale of the resulting Trail of Tears in 1838–39 has been told many times, but it becomes no less tragic through repetition.27

Napoleon’s ascent to power in France after 1798 coincided with the military failure of French and British forces in Haiti. Determined to put down the successful slave revolt led by Toussaint L’Ouverture, he dispatched a major force under his brother-in-law to the Caribbean. As a complement to anticipated success in Haiti, Napoleon planned to rebuild the French Empire in North America and persuaded Spain in a secret treaty to transfer its Louisiana colony back to France (it had been French until 1763). This gave France once again a presence all the way from the Gulf of Mexico to the Canadian border.28

The Treaty of San Ildefonso, as it was called, was signed in 1800. When news of it leaked out the following year, Jefferson had become president and he was deeply concerned. The United States faced the prospect of a powerful and imperially ambitious neighbor across the whole western side of the Mississippi River. Even more worrying was French control of New Orleans at the mouth of the river, through which so much of US trade was bound to pass.29

Jefferson neither wanted, nor expected, to acquire the whole of Louisiana.30 Instead, he authorized his ambassador in Paris, together with James Monroe, to explore the possibility of a much more modest territorial cession including New Orleans and a small part of the lower Mississippi on the western bank. This would have been sufficient to secure US strategic interests. The budget was set at $10 million.

By one of the ironies of history, negotiations began in Paris not long after the French army had been crushed in Haiti, laying waste to Napoleon’s dream of reviving the French Empire in North America. Napoleon now had no need of Louisiana and offered to sell the whole of it, including New Orleans, for $15 million. The offer was accepted without waiting for Jefferson’s approval.

Jefferson was not the sort of man to pass up an opportunity to expand his “empire for liberty,” and the Louisiana Purchase, which doubled the size of territory controlled by the federal government, is usually portrayed as the greatest land cession in history (Map 3).31 Yet it is not at all clear that this was so. The only secure title in the cession was to New Orleans and a small area in the lower Mississippi. It would take the United States over a century to secure title to the rest, by which time twenty thousand Americans and countless Indians had been killed, with at least $750 million spent on military campaigns (not to mention the millions of dollars for land cessions from, and annuities to, the Native Americans themselves).

Jefferson was so uncertain of what he had bought that he posed a set of questions to William Claiborne, the first governor of the new territories. His answers are illuminating:

There are I believe, [no maps] extant that can be depended upon. . . . I am also informed, that a number of partial but accurate Geographical Sketches of that Country, have been taken by different Spanish officers; but that it has been the policy of their Gov [to] prevent the publication of them. . . . On this question [regarding boundaries], I have not been able to obtain any satisfactory information. . . . The information [on white settlers] I have as yet been able to collect concerning the population, position &c of the several divisions, is not sufficiently authentic, to justify my hazarding an Answer in detail to this question. . . . [On Indian population] I am unable to make an estimate with the accuracy required.32

Undeterred by this and other potential obstacles,33 Jefferson proceeded to organize the French territories along now traditional lines. This, however, was no simple matter. The cession included land that would in time become the whole of Arkansas, Kansas, Iowa, Missouri, Nebraska, and Oklahoma and parts of Colorado, Louisiana, Minnesota, Montana, New Mexico, North Dakota, South Dakota, Texas, and Wyoming (Map 3).34

After a brief period of military rule, the Territory of Orleans was formed in 1804 in what would become (approximately) the State of Louisiana, and the rest of the French territories were designated the District of Louisiana (it would be called the Territory of Louisiana from 1805 onward). The white settlers of Orleans Territory were a mixture of French, British, Spanish, American, and German (there were also many “free people of color”). Far from being delighted with their new status, however, there were many complaints from these colonial subjects—especially the French—whose objections were very similar to those in European colonies:

Map 3. French and Spanish territories

[The general causes of discontent are] the sudden introduction of the English language, which hardly anybody understands, into the daily exercise of public authority and in the most important acts of private life; the affrays and tumults resulting from the struggle for pre-eminence, and the preference shown for American over French dances at public balls; the invasion of bayonets into the halls of amusement and the closing of halls; the active participation of the American general and governor in those quarrels; the revolting partiality exhibited in favor of Americans or Englishmen, both in the audiences granted by the authorities and in the judgments rendered; the marked substitution of American for Creole majorities in all administrative and judicial bodies; the arbitrary mixture of old usages with new ones, under pretext of change of domination; the intemperate speeches; the scandalous orgies; the savage manners and habits; the wretched appointments to office.35

It is doubtful if the president was much troubled by any of this. Of more concern to Jefferson was the use to which the new territories would be put. His preferred solution was a constitutional amendment under which the new territories would have become a vast Indian reserve allowing not only for the removal to the west of those Indians on the east of the Mississippi River but also for the removal to the east of those whites on the west. However, Congress defeated his proposal, not wishing to put any constraints on white settlement.

The stage was therefore set for a great human tragedy, the first act of which had already taken place without Jefferson even knowing.36 This was the death through disease of perhaps one-third of all Indians in the new territories and further west starting in the 1780s as a result of smallpox, cholera, bubonic plague, streptococcal infections, influenza, measles, and whooping cough. Indeed, a smallpox epidemic in 1837 on the northern plains cut in half the Indian population in one year.37

The Indians in the area ceded to the United States by France had adapted to their environment in two very different ways that would have profound implications for the form that empire building took. Along the Missouri and its tributaries, as well as the other rivers that flowed east into the lower Mississippi, the Indians lived in riverine horticultural villages where farming was the principal activity. In the uplands west, southwest, and northwest of the Missouri as far as the Rocky Mountains, they formed nomadic hunting bands.

The village dwellers had a lifestyle with which the federal government was familiar. Treaties were signed almost immediately providing for land cessions, removal further west, and the payment of gifts and annuities. Of course, the lands to which these Indians were removed were not empty, and this necessitated further treaties with those most affected. Nonetheless, by 1812 Orleans Territory was ready to enter the Union as the slave-owning State of Louisiana. The Territory of Louisiana was then renamed Missouri Territory. In 1819 it was split, with the southern part becoming Arkansaw [sic] Territory.38

This division was designed to prepare the way for a small part of Missouri Territory, where cotton farming was rapidly expanding, to enter the Union as the State of Missouri. However, this proved to be highly controversial because of the use of slave labor in the territory. It took two years before the (in)famous Missouri Compromise was thrashed out, banning slavery above latitude 36° 30´ north except in the case of Missouri itself.

At this point the federal government and Congress gave serious thought to a “permanent” settlement of the Indian population through the creation of a territory for Indians bounded on the east by Arkansas Territory39 and Missouri State, on the south by the Red River, on the west by Mexico,40 and on the northern boundary by the Platte River. In this way, claimed Secretary of War John C. Calhoun, the United States would reach a satisfactory solution to competition for land between whites and Indians: “One of the greatest evils to which they [Indians] are subject is that incessant pressure of our population, which forces them from seat to seat. . . . To guard against this evil . . . there ought to be the strongest and the most solemn assurance that the country given them should be theirs, as a permanent home for themselves and their posterity.” 41

This land was formally declared to be Indian Territory in 1830, and four years later Congress debated a bill for it to become “organized” with a confederated government formed by the tribes, a nonvoting delegate sent to Washington, DC, and eventual admission to the Union as a state. Unfortunately, the bill did not pass and Indian Territory remained “unorganized.” It therefore lacked any legal protections and became instead a dumping ground for Indians from the east under the removal policy.

After the admission of Missouri as a state in 1821, the rest of Missouri Territory—stretching all the way to the Canadian border—became known at first as “unorganized territory,” meaning that Congress had not yet passed organic acts to divide it into different administrative units. In this vast area, whites had a growing presence through trade, forts, trails, and missions. However, the pressure on the nomadic Native Americans was not yet severe. Indeed, it is doubtful if the settlers outnumbered the Indians in the whole of the Louisiana Purchase—let alone on the northern plains—when Arkansas became a state in 1836.

By midcentury, however, everything suddenly changed. Oregon had been acquired, Texas was annexed, Mexico lost half its territory, and the United States found itself with a new coastline stretching all the way from Baja California to British Columbia.42 The gold mines of California, the fertile valleys of the West Coast, and the fur trade on the Pacific inevitably attracted a steady stream of settlers.

The Native Americans of the old French territories were now no longer at the western extremities of the United States. Instead, they were in the middle and, from the point of view of the settlers and the federal government, in the way. Trails needed to be prepared, and roads built, and in a few years railways and telegraphs would need to be laid down. To support this, an enhanced network of military forts and trading posts had to be established. The increased flow of settlers disrupted the wildlife on which nomadic life depended and, to make matters worse, industrialization in the east was creating a new type of demand for buffalo hides that no longer required skilled Indian labor to meet it.

At the Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1851, the federal government signaled the change that was coming. Many of the Plains tribes, including the Mandan, Crow, Blackfeet, Cheyenne, and Arapahoe, were obliged not only to accept reduced hunting ranges that would in due course become reservations but also to permit safe passage across their land by migrants on the Oregon Trail and to allow the construction of roads and forts on their territories. In return, the federal government promised to keep out settlers—a promise that was broken within a few years following the discovery of gold near Pike’s Peak.

In 1854 the “unorganized” land west of Arkansas, Missouri, and Iowa States43 and Minnesota Territory was formed into Kansas and Nebraska Territory, cutting deep into hunting grounds that the Indians had assumed was theirs to use indefinitely. The Kansas-Nebraska Act was the prelude to the Civil War, as every student of US history is aware, since it effectively repealed the Missouri Compromise on slavery. However, the Civil War also had major implications for the Native Americans since, once again, the majority of the tribes backed the losing side.44

By the end of the war, whatever goodwill toward the Indians that might have existed in Washington, DC, had evaporated (Box 1.3). Native Americans were subjected to a sustained attack that almost completely destroyed what remained of their societies. The assault had numerous dimensions—economic, cultural, legal, political, and religious—and involved armed force, including massacres. It was a genocide that had reduced the Native American population to its lowest point in history by 1900.45

BOX 1.3

ELY SAMUEL PARKER (1828–95)

The expansion of the US empire across the continent relied on agents acting for or on behalf of the federal government. Among these agents were governors, judges, military officers, missionaries, and superintendents of trade. Some of the most important, however, were appointed to deal exclusively with Indian affairs.

President Washington had given the War Department responsibility for Indian matters, including supervision of the various Trade and Intercourse Acts, and Congress had approved in 1824 a Bureau of Indian Affairs within the War Department. When in 1849 responsibility for Indian affairs was handed to the Department of the Interior, the bureau moved with it.

The most important agent in the bureau was the commissioner for Indian affairs, and the appointment was always a white man until 1869, when President Ulysses S. Grant (1869–77) appointed Ely Samuel Parker to the post. Parker was the son of a Seneca chief who had been born on the Tonawanda reservation in New York and given the name Donehogawa at birth. He had been formally educated at a missionary school. His efforts to study law were rebuffed because he was an Indian and therefore not a US citizen, but he was able to train as an engineer. This brought him to the attention of President Grant before the Civil War.

The appointment was a bold one, but the timing was terrible for Parker. The Bureau of Indian Affairs was extremely corrupt, its board composed only of whites, and US action—despite Grant’s proclaimed “peace policy”—deeply hostile to Indians. Indeed, one of Parker’s first tasks at the start of his tenure was to investigate the massacre of the Piegan Blackfeet by the US military.

Parker secured some successes, but his efforts to reduce corruption in the bureau and blocking of illegal mining in Wyoming made him many enemies. He was charged in Congress on thirteen counts, including misappropriation of funds. Although eventually cleared of all charges, he was so disgusted at his treatment that he resigned his post in the summer of 1871.

The federal government signaled the change by ending the treaty system. Henceforth, Indians would not be treated as “sovereign nations” but as dependent tribes with whom one-sided negotiations would take place. One of the last treaties to be signed, however, was also one of the most important. In the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie, the federal government guaranteed to the Lakota Indians ownership of the Black Hills in South Dakota and closed the Powder River Country to whites. Both “guarantees” would be withdrawn, leading to some of the bloodiest incidents in the Indian Wars before the final massacre at Wounded Knee in 1890.

As the genocide was drawing to a close, Congress prepared the legislation to draw the remaining territories in the north of the Louisiana Purchase—Dakota, Montana, and Wyoming—into the Union. It had been a long process, during which Congress had been unable to resist the temptation to meddle in territorial affairs. Indeed, by the 1880s the restrictions on what territorial legislatures could do had expanded enormously:

Among the more important of these limitations now in force are those prohibiting the passage of acts interfering with the primary disposal of the soil, imposing a tax on property of the United States, taxing the property of non-residents higher than that of residents, having a special or local character in respect to any of a large number of enumerated cases, such as divorce, regulating county or township affairs, the assessment and collection of taxes, the punishment of crimes, the granting to any corporation, association or individual of any special or exclusive privilege, immunity or franchise, etc., or generally in any other case where a general law could be made applicable. No special or special charter to any private corporation can be granted, but a general incorporation law may be enacted. Other limitations upon the power of Territories are those prohibiting the Territories from contracting any debt except for certain purposes, and even then only to the total amount not exceeding a certain percentum of the assessed value of property in the Territory for purposes of taxation.46

Under these circumstances, it is not surprising that many white settlers in the territories chafed at their colonial status. One had the audacity to compare an unpopular governor with George III, while another described the territories as “mere colonies, occupying much the same relation to the General Government as the colonies did to the British government prior to the Revolution.” 47

Delegate Martin Maginnis of Montana Territory went even further, telling the House of Representatives in 1884: “The present Territorial system . . . is the most infamous system of colonial government that was ever seen on the face of the globe. . . . [The territories] are the colonies of your Republic, situated three thousand miles away from Washington by land, as the thirteen colonies were situated three thousand miles away from London by water. And it is a strange thing that the fathers of our Republic . . . established a colonial government as much worse than that which they revolted against as one form of such government can be worse than another.” 48

The colonial status of these northern territories ended in 1889–90 when they joined the Union. At that moment, Congress also created the Territory of Oklahoma from the western portion of Indian Territory, and the long process of attrition of Indian land rights was almost at an end. The Dawes Act of 1887, suppressing communal land ownership, was gradually extended to Indian Territory and land cessions accelerated. The two territories were then admitted to the Union as the State of Oklahoma in 1907, the last state wholly within the Louisiana Purchase of 1803 to do so.49

The United States, following the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, continued to share a boundary with Spain in the south (the Floridas), but the exact border between the two empires was again in dispute as the United States insisted West Florida was included in the sale. Spain’s colony of Nueva España (soon to become Mexico) was now the neighbor in the west, although where the boundary ran was even more contentious than in West Florida.

In the north, the boundary was still with Great Britain, but no final agreement had as yet been reached on where the frontier lay west of the Great Lakes. And in the Pacific Northwest, boundary disputes involved not just the United States, the United Kingdom, and Spain but also Russia, whose territorial empire had spread across the Pacific to the Americas. Thus, the scene was set for a territorial struggle between old and new empires that would take several decades to resolve (Map 3).

During its brief period of British colonial rule (1763–83), Florida had been divided into West and East at the Apalachicola River, with separate capitals at Pensacola and St. Augustine, and this was how Spain had administered the colony on its retrocession. West Florida included Baton Rouge on the east side of the Mississippi River, although a majority of the population was American by 1803. By the 1795 Treaty of San Lorenzo, Spain had given up its claim to the area north of the 31st parallel, but it had never relinquished its claim on West Florida, and France always understood that to be the case.

The US claim that Louisiana included West Florida was therefore very weak and indeed contradicted by the 1795 Treaty of San Lorenzo.50 Undaunted, however, Congress passed the Mobile Act in 1804, annexing most of West Florida to Mississippi Territory. Spain protested and was strong enough to prevent the upstart empire from enforcing its claim by defeating a filibuster expedition that same year. President Jefferson did not respond and contented himself with opening a customs post on the Mobile River just north of the Spanish border.

Spanish ability to resist further US encroachment was fatally weakened by Napoleon’s invasion of the Iberian Peninsula in 1808. Royalist troops in the Americas were left to fend for themselves, with little or no hope of reinforcement. US insurgents seized Baton Rouge in 1810, giving President Madison the excuse he needed to annex West Florida as far as the Pearl River and include it in Orleans Territory.

This time Spanish protests could not be backed up by force, and worse was to come. When the War of 1812 erupted, Great Britain saw an opportunity to encircle the United States by invading from the south, seizing New Orleans and controlling the Mississippi. Andrew Jackson was dispatched to deal with this threat and, without declaring war on Spain, defeated the British and secured the remainder of West Florida with the exception of Pensacola (occupied but returned to Spain in 1815).

The defeat of Napoleon in 1814 brought Fernando VII back to power in Spain. This should have marked a reassertion of Spanish authority in the Floridas, but the opportunity was undermined by the wars of independence in Latin America. The Floridas were too marginal in Spanish imperial thinking and the royalist garrison was left to fend for itself. When Jackson invaded East Florida in 1818, ostensibly in hot pursuit of the Seminoles fleeing from Georgia,51 Spain was unable to respond. By the middle of the year, Spanish authority was reduced to St. Augustine.

Jackson’s campaign, although never officially authorized by President Monroe, gave the secretary of state (John Quincy Adams) a huge advantage in the negotiations with his Spanish counterpart (Don Luis de Onís y González) that had been going on for some years. When the Adams-Onís Treaty was signed in 1819, it gave all of Florida to the United States. Ratification was delayed by two years, but—following a brief period of US military rule—the Territory of Florida came into being in 1822.

Since most of the Spaniards left for Cuba, the white population was now very small. However, the Indian population was still substantial. The federal government therefore pressured the Seminole chiefs to sign the Treaty of Moultrie Creek in 1823, which established a reservation in the middle of Florida with an annuity guaranteed for twenty years. Settlers and their slaves now moved into Florida to plant cotton and raise other cash crops.

Florida was big enough to accommodate the needs of planters and Seminoles, as well as the requirements of the numerous free blacks who resided in the territory. However, any chance of accommodation was destroyed by Jackson’s Indian Removal Act. The Seminole chiefs were summoned to a new meeting in 1832 and tricked into signing the Treaty of Fort Payne requiring them to move west of the Mississippi. Many Seminoles, including Osceola, resisted removal, and the Second Seminole War began in 1835.

It was one of the bloodiest wars in US imperial history and included the massacre of Major Francis L. Dade and his two companies.52 The Seminoles never fully surrendered, but the survivors were driven further south into the Everglades (Box 1.4). At the end of the war in 1842, Congress passed the Armed Occupation Act giving 160 acres of land to any settlers willing to improve the land in the south of the territory and defend themselves from Indians. Florida was now ready for statehood and joined the Union in 1845. The southern boundary of the United States was now the Caribbean sea and the Gulf of Mexico.

The Adams-Onís Treaty did not limit itself to the transfer of Florida. It also set the Spanish-American boundary throughout the continent. Texas remained part of Nueva España, whose northern border was now set at 42° north. Beyond that—up to British-controlled Canada and Russian-controlled Alaska—was still undefined, but a door to the Pacific through what would now be called Oregon Country had been opened for the United States.

Sovereignty over Oregon Country would now be disputed between three imperial powers: Great Britain, Russia, and the United States. Yet it was already the home of several tribes, some of whom lived from fishing or agriculture and had no desire to leave. White sailors, trappers, and explorers from the 1770s onward had brought with them a series of diseases that had reduced the Indians’ numbers, but there were still estimated to be 110,000 as late as 1835.53 At that time, there were less than one thousand white settlers in the region.

None of the imperial powers had a strong claim on Oregon Country. The Russians had been on the northwest Pacific for the longest, following the epic voyage of Vitus Bering in 1741 down the coast of Alaska. The British had gained a foothold after the Nootka Sound Conventions with Spain54 and the overland journey to the Pacific of Alexander Mackenzie in the 1790s. The United States pointed to the voyage of Robert Gray in 1792 to the mouth of the Columbia River and the explorations of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, who reached Oregon Country in 1805.55

BOX 1.4

ETHAN ALLEN HITCHCOCK (1798–1870)

US territories would eventually be filled by settlers, but they first had to be secured by the military. This meant that army officers played a crucial role in extending the US empire across the continent. Some of these men would go on to play a prominent part in politics, even occupying the presidency in a few cases. Most were unreservedly committed to the imperialist project, but there was a handful who were able to see the exercise more objectively while remaining loyal.

One such officer was Ethan Allen Hitchcock, the grandson of a revolutionary war hero. Graduating from the US Military Academy in 1817, he volunteered to serve with Andrew Jackson in the First Seminole War but was turned down. By the time the second war broke out in 1835, however, he was a captain and saw service.

Hitchcock kept a detailed diary, an edited version of which was published posthumously in 1909. His observations on the Second Seminole War were remarkable, documenting the folly and dishonesty of his military superiors: “I confess to a very considerable disgust in this service. I remember the cause of the war, and that annoys me. I think of the folly and stupidity with which it has been conducted, particularly of the puerile character of the present commanding general, and I am quite out of patience” (Hitchcock, Fifty Years in Camp and Field, 123).

After the war, by this time a major, Hitchcock was sent to Indian Territory to investigate the allegations of fraud raised against the contractors paid by the federal government to carry out removal of the Five Civilized Tribes. His diary entries were not only full of insight (see Foreman, A Traveler in Indian Territory) but also provided the basis for his searing report to President John Tyler in 1842.

Hitchcock, by now a lieutenant colonel, saw service in the Mexican-American War where his diary once again was very revealing: “Our people ought to be damned for their impudent arrogance and domineering presumption” (192). He would eventually rise to the rank of major general and commanded the Pacific Division, during which time he visited Oregon Territory.

Undaunted by the weakness of their claims, the three powers had proceeded to establish a presence. Oregon Country was desired not just for its furs, fishing, timber, and agricultural land (minerals would come later) but also for its coastline, providing magnificent harbors from which the Pacific could be crossed. And, as always in imperial rivalry, there was the constant worry of other powers arriving first and blocking access to the others.

The competition between the United States and the United Kingdom focused at first on the fur trade. John Jacob Astor opened a trading post (modestly named Astoria) at the mouth of the Columbia River in 1811, which was unceremoniously seized by the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1817.56 The following year the two countries reached agreement that the boundary between Canada and the United States from the Great Lakes to the Rockies should follow the 49th parallel while sovereignty would be shared west of the continental divide.

Russia, well established in Alaska and with a military presence in California, was more ambitious. The czar issued a ukase in 1821 claiming sovereignty on the coast as far south as the 51st parallel and an exclusive maritime zone to the west. A second ukase granted a Russian company a twenty-year monopoly on trading in this area.57

John Quincy Adams, as secretary of state, responded with a wildly ambitious US claim of sovereignty up to 61° north. More significantly for hemispheric history, however, was the response of President Monroe. In December 1823, during his seventh annual message to Congress, the president outlined what would become known as the Monroe Doctrine:

At the proposal of the Russian Imperial Government, made through the minister of the Emperor residing here, a full power and instructions have been transmitted to the minister of the United States at St. Petersburg to arrange by amicable negotiation the respective rights and interests of the two nations on the northwest coast of this continent. . . . In the discussions to which this interest has given rise and in the arrangements by which they may terminate the occasion has been judged proper for asserting, as a principle in which the rights and interests of the United States are involved, that the American continents, by the free and independent condition which they have assumed and maintain, are henceforth not to be considered as subjects for future colonization by any European powers.58

The following year the three rivals—Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States—agreed that 54° 40´ north would be the southern limit of the Russian claim and also the border between Russia and British Columbia. It did not, of course, mean that the US claim would extend so far north, although some hotheads assumed that it would (“Fifty-four forty or fight” was their rallying cry). It did mean, however, that imperial control of Oregon Country between the new northern border and the 42nd parallel was now a simple imperialist rivalry between the United Kingdom and the United States.

At this point the United States unleashed its not-so-secret weapon: settlers. The British, or at least the Hudson’s Bay Company, preferred to see Oregon Country free of settlers because of the damage they did to the fur trade. US settlers (including missionaries), however, started following in the footsteps of Lewis and Clark in the 1830s. By the mid-1840s British interest in Oregon Country had diminished, while US interest was growing. After some saber rattling by both sides, the boundary was settled at the 49th parallel in 1846.

The United States had therefore acquired a Pacific coastline even before the start of the Mexican-American War (see Chapter 2). However, the task of colonization would take many years to complete. Oregon Territory was formed in 1848 and Washington Territory was split from it in 1853. Ten years later Idaho Territory was formed from part of Washington Territory (the other parts coming from Dakota and Nebraska Territories). The western portion of Oregon Territory became a state in 1859, but it was not until thirty years later that Washington and Idaho joined the Union.59

Why did statehood take so long? When the first census of Oregon Territory was taken in 1850, there were still only 13,294 settlers (far less than the Native Americans). However, inward migration accelerated after the federal government took control and the settlers wanted to take the land occupied by the Indians (the fur trade was now in steep decline). This inevitably meant confrontation, condemning the region to decades of warfare.

Congress appointed three commissioners in 1850 to secure the land, with instructions that were none too subtle (“to free the land west of the Cascades entirely of Indian title and to move all the Indians to some spot to the east”).60 These orders were then carried out through a series of treaties that aimed to push the Indians away from the lush valleys in the south of the territory where the bulk of the settlers sought to make their homes.

Among the numerous Indian tribes were the Niimíipu, who had been called Nez Perce61 by French trappers. Members of the tribe, which at the time numbered around twelve thousand, had helped Lewis and Clark when the expedition’s food supplies ran low after crossing the Continental Divide, but this act of kindness had been long forgotten when the Walla Walla Council met in 1855. The resulting treaties required the Nez Perce to cede 7.5 million acres and live on a reservation, where—unfortunately for them—gold would soon be discovered. Inevitably, this led to a flood of illegal settlers.

Another treaty would now be drawn up (in 1863), requiring the Nez Perce to relinquish 90 percent of their reservation.62 This time, however, many chiefs refused to sign, and the stage was set for the Nez Perce War that erupted in 1877. The story of this legendary conflict, in which nearly three thousand members of the tribe were pursued by the US military over more than one thousand miles, has been told repeatedly, but it had deadly consequences for the Nez Perce. By 1900, squeezed into a small reservation in Idaho, the population of the tribe had dwindled to nineteen hundred.