With the acquisition of Oregon, the United States should have had enough land to satisfy all but the most ardent imperialists. However, the non-Indian population was expanding fast and increased by one-third between 1830 and 1840, by which time it had reached seventeen million. The expansionists were therefore able to argue for continued territorial growth on the grounds that land would still be needed for future as well as current settlers.

The argument in favor of more land, however, was no longer as widely supported as it had been at the time of independence. The quasi-consensus in favor of the creation of the Northwest and Southwest Territories, the Louisiana Purchase, the acquisition of the Floridas, and the establishment of the Oregon Territory would now break down. This did not mean that the imperial project was over, but it did mean that it would become more contested.

The main problem was, of course, slavery. The southern states favored continued expansion partly because of the desire for more land, but above all to bring new states into the Union to protect the “peculiar institution.” Not surprisingly, many of the citizens of the northern states opposed expansion for exactly the same reason.

Since the south could not outvote the north under normal circumstances—still less muster the two-thirds majority needed for certain legislative purposes—it might be assumed that the north would block expansion if the only reason for it was to bolster slavery. However, elites in the northern states often favored continued expansion for reasons that had nothing to do with slavery and which went beyond the traditional argument based on additional land.

One of these was the rise of the United States as an industrial power. Although still behind the United Kingdom, America was catching up quickly as a producer and even exporter of manufactured goods. Its gross domestic product (GDP) was growing rapidly, and US trade—at least in the first half of the nineteenth century—was growing even faster than GDP. This meant that the United States now had a stronger interest in trade and foreign markets than at the time of independence.

World trade in the first half of the nineteenth century was heavily influenced by systems of imperial preference, under which empires not only discriminated against imports into the metropolitan states but also into their colonies if they originated from outside the empire. The United States was therefore at a disadvantage when trading with European powers and their colonies. Ending discrimination against US exports, or even shifting it in favor of the United States, was becoming an important strategic priority, and this meant an America big and powerful enough to rival other empires.

In the context of the 1840s, US territorial expansion could realistically only take place northward or southward. The dream of acquiring British-controlled Canada had not died with the War of 1812, and friction would remain with Great Britain for many years to come.1 However, with the adjustment of the Maine border in 1842 and the settlement of the dispute over Oregon Country a few years later, the prospects of northern expansion did not look promising.

That left expansion toward the south, where Mexican rebels had defeated Spain and created an independent state in 1821. Although the US border with the Spanish colony had been agreed on in 1819, Mexico discovered soon after its independence what Native American tribes had known for decades: US settlers did not regard border treaties as sacrosanct, were prepared to challenge them by force if necessary, and could usually expect a sympathetic response from the federal government.

The result was the Texan War of Independence (1835–36), strongly supported by the southern states, who assumed a Texas where slavery was legal would soon join the Union. That did indeed happen a decade later, by which time a further argument for imperial expansion had come to prominence in the United States. This was Manifest Destiny, a rationale for expansion that had been implicit since independence but which was now rendered explicit.

Manifest Destiny was an ideological, racist, and quasi-religious doctrine that underpinned a US claim to all lands in North America from the Atlantic to the Pacific. It was always controversial, but in the hands of a skilled politician could become a powerful tool in favor of territorial aggrandizement. Such a man was President James K. Polk (1845–49), who used the argument to great effect to launch a war against Mexico and strip her of half her territory. This not only vastly expanded the size of the United States but also gave her a long Pacific coastline.

The United States was now truly a transcontinental power, and this brought new challenges at a time when the two coasts were still only connected by sea travel (except for those prepared to undertake the long and dangerous overland route). Most trade in goods between the coasts was required to go by sea around Cape Horn in South America—a slow and expensive journey. The United States now also needed two navies to patrol its shores. Only a canal at some point across the Americas could alleviate this situation. The search for a transit route therefore became a US priority.

Many routes were considered, but a canal through Nicaragua quickly established itself as the favorite. However, other imperial powers—especially Great Britain and France—had come to the same conclusion. Thus, a small Central American state became the focus not just of close US attention but also of intense imperial rivalries that would endure for decades. It also attracted the interest of an American filibuster and supporter of slavery—William Walker.

Nicaragua came close to annexation by the United States in the 1850s, but imperial ambition was thwarted first through the defeat of Walker by the Central Americans and second by the Civil War. US interest in Nicaragua did not, however, disappear, and the country would become a US protectorate at the beginning of the twentieth century.

The Nicaraguan route was the preferred one for most of the nineteenth century. Although longer by distance than the route through Panama (a province of Colombia until 1903), the latter was thought to be more costly and more difficult. Indeed, this had been borne out by the failure of Ferdinand de Lesseps’s canal project in the 1880s. The United States, however, decided to hedge its bets in the 1890s and signed an agreement with Colombia for exclusive control of any canal that might be built.

The story of how the refusal of the Colombian Congress to ratify the treaty led to Panamanian “independence” and the construction of the canal is well known. Yet it is also an illustration of the different forms that US imperialism could take. Panama would—like Nicaragua a few years later—become a US protectorate, while the Panama Canal Zone became a full-blown American territory. The sovereignty of the rest of Central America was severely compromised as a result.

The advance of the American empire southward represented a key shift in the imperial project. While muscular diplomacy had been used to secure territory in North America from European empires, military force was used to do the same with Mexico, Colombia, and Nicaragua. This was naked imperial aggression that could not be disguised by the use of slogans such as Manifest Destiny, and it could no longer be claimed that American empire was based only on western expansion and settler colonialism. In addition, this was now an empire that aspired to geopolitical leadership with access to two oceans and prospects for hegemony in Latin America and the Pacific.

The location of the border between French and Spanish territories in North America had not been definitively settled when Louisiana was purchased in 1803. This allowed Presidents Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and James Monroe to claim that Louisiana included at least part of what is now Texas. The claim was very flimsy, but John Quincy Adams cited it repeatedly in his protracted negotiations with his Spanish counterpart for a border treaty.

Although the claim was weak, it was asserted with such authority that many Americans came to believe it. At the same time, revolutionaries in Nueva España were struggling to break free from Spanish control. The result was a series of filibusters into Spanish-controlled Texas by Mexican rebels and US settlers. Indeed, the first filibuster in 1811 was a joint venture between the two although it quickly fell apart when the different goals of the US and Mexican leaders became apparent. Filibusters continued for a decade, the final one being led by James Long in 1821.

Long, unlike his filibustering predecessors, did not receive overt or covert support from the federal government. The reason was simple. The Adams-Onís Treaty, signed in 1819, had recognized that Texas was a province of the Spanish colony of Nueva España (Adams and President Monroe had accepted this because Spain had agreed to transfer the Floridas to the United States). It would therefore have been an act of extreme bad faith to support Long’s filibuster so soon after the boundary had been settled.

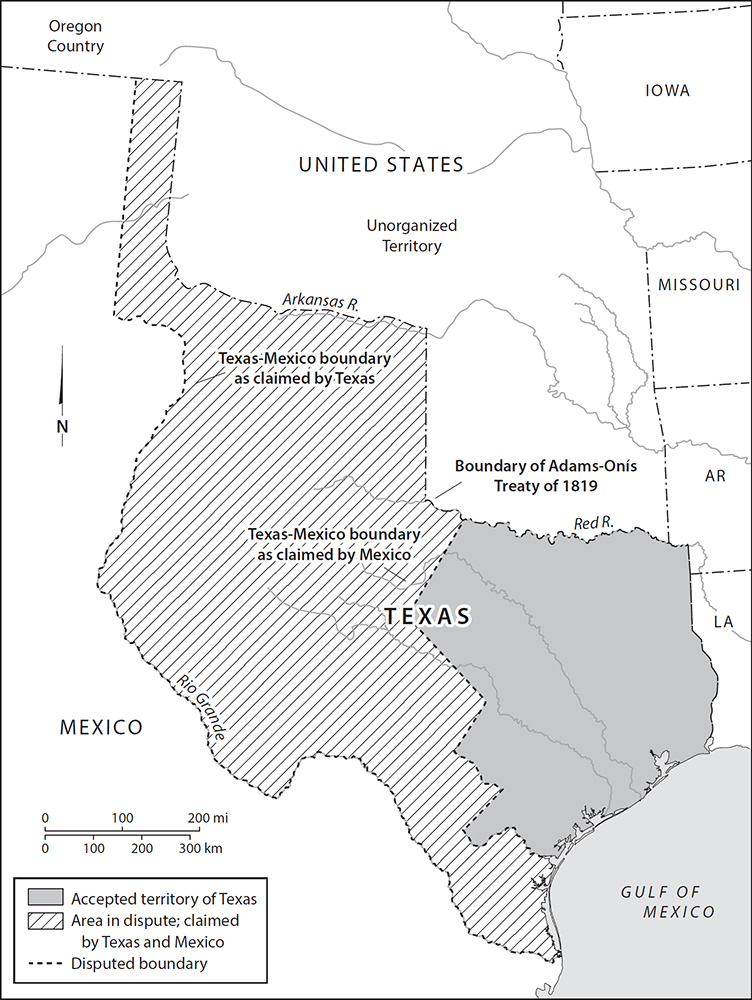

Ratification of the Adams-Onís Treaty was delayed so long that Mexico had become independent (in 1821) before it could be enforced. However, the boundary between Mexico and the United States was later reaffirmed by both sides as being the same as agreed to in the treaty (Map 4). The Sabine River therefore marked where Louisiana ended and Texas started. Mexico, briefly an empire under Agustín Iturbide until the establishment of a republic in 1823, then organized its territory into states with Texas joined to Coahuila as one province.

The transition from part of the Spanish Empire to Mexican republic did not alter the facts on the ground as far as Texas was concerned. This was a fertile area, suitable for growing cotton, tobacco, sugar, and other cash crops, where the Indian population far outnumbered Spanish settlers. Furthermore, the Indians—mainly Cherokees in the east, Wichitas in the center, and Comanches in the west—were not inclined to let their land be taken from them without a fight.

Map 4. Texas, 1836–45

Texas was also an area that the Spanish had struggled to control militarily because of the semiarid and depopulated regions that separated it from the rest of Mexico and through which royalist armies had to pass. Indeed, such was the difficulty of protecting settlers against Indians that the Spanish abandoned Texas for long periods. The Comanches in particular had been very successful at extending their own area of control, known as Comanchería, as their skill on horseback had given them an advantage in mobile warfare.2

At the time that Spanish rule was coming to an end, there were only a small number of settlers in Texas, and the royalist forces could not guarantee their safety against Indian attacks. It was the Indian threat, rather than the filibusters, which persuaded the authorities in 1819 to create a system of land grants designed to encourage American immigration. Even so, the Spanish were careful to put many restrictions on the immigrants in order to ensure that they did not become a Trojan horse. These included an oath of allegiance to the Spanish crown and the adoption of Roman Catholicism.

Moses Austin, the first beneficiary of this empresario system, seemed an ideal candidate from the royalist perspective as he had lived as a Spanish subject in Louisiana before the Treaty of Ildefonso. However, Moses Austin died before he could fulfill the contract. It was left to his son, Stephen, to renegotiate the details with the Mexican government after independence.

Stephen Austin was at first a loyal Mexican subject and helped to put down the so-called Fredonia Republic set up by one of the US colonists in 1826. However, there was one subject that gave him perpetual difficulty with the authorities, and that was slavery. The Spanish grant to his father had not mentioned slaves, meaning that the colonists felt free to import them. Yet Mexico after independence gradually phased out the practice.

Stephen Austin worked hard to ensure that Texas was exempt from all the slavery legislation passed by Mexico. In 1825 he wrote, “If slavery should be prohibited immigration would be stopped, or if any came, they would be of the lower economic class, able only to eke out a bare existence and unable to promote the prosperity of the country; for in the cultivation of corn, cotton, and sugar, the principal products of the province, the use of many laborers, of slaves who are accustomed to the type of work, is indispensable.”3

In these efforts he had some success, but the decision of the Mexican government in 1829 to ban slavery altogether put a serious doubt over the whole scheme of colonization. Although Austin achieved a temporary reprieve from this nationwide ban, his efforts were undermined the following year by the government’s decision to stop foreign immigration. This was clearly aimed at US colonists, who already outnumbered Mexicans in Texas and whose allegiance to the state—let alone adoption of Catholicism—was now suspect.

By this time Andrew Jackson had assumed the presidency. For years he had lambasted John Quincy Adams for not including Texas in the treaty that bears his name (although Adams had tried to make amends during his own presidency by offering to buy Texas from the Mexicans, he had been rebuffed). Jackson was therefore susceptible to the charms of an unscrupulous entrepreneur, Anthony Butler, who convinced him that Texas could be bought for $5 million.

Jackson’s overtures were also rebuffed, but by now the Mexican authorities were becoming justifiably paranoid about the possibility of losing Texas. Don Manuel Mier y Terán, the Mexican boundary commissioner, wrote to his superiors, “The wealthy Americans of Louisiana and other Western states are anxious to secure land in Texas for speculation but they are restrained by the laws prohibiting slavery. . . . The repeal of these laws is a point toward which the colonists are directing their efforts. . . . Therefore, I now warn you to take timely measures. Texas could throw the whole nation into revolution.” 4 Steps were then taken to occupy the province militarily and to establish colonies of Mexicans whose loyalty could be trusted. In addition, the tax holiday on customs duties enjoyed by the colonists was phased out and, finally, US immigration itself was stopped.

None of this went down well with the US colonists, whose attachment to Mexico—except for Austin—had always been skin-deep. Yet as late as 1832 in the Convention of Texas their representatives were still saying that “a decided declaration should be made by the people of Texas . . . of our firm and unshaken adherence to the Mexican Confederation and Constitution and our readiness to do our duty as Mexican Citizens.”5 However, the decision of President Antonio López de Santa Anna in 1834 to suppress Congress and establish a dictatorship, as well as his decision to refuse Austin’s request for a separation of Texas from Coahuila, provoked the American colonists into rebellion.

When the war started, events moved fast and independence, followed by annexation to the United States, quickly became the colonists’ priority. The defeat of the Mexican Army and the capture of Santa Anna at San Jacinto in April 1836 did indeed lead to Texan independence and a unanimous request for annexation. However, there was initially a deafening silence on the US side despite the fact that Jackson was still president.

This was not due to a change of heart by the president on the need for annexation (he would later write “we must regain Texas, peaceably if we can, forcibly if we must”). He had, for example, dispatched General Edmund P. Gaines during the war to the area between the Sabine and Nueces Rivers.6 Yet Jackson proceeded with uncharacteristic caution for several reasons. First, he did not want the issue of slavery to undermine the chances of his protégé Martin Van Buren in the upcoming presidential election and, second, he did not want to start a war with Mexico. It was not until his final hours in office that Jackson even recognized Texas as an independent state.

By this time the Texans had drawn up their own constitution that not only legalized slavery but also the importation of slaves from the United States: “All persons of color who were slaves for life previous to their emigration to Texas, and who are now held in bondage, shall remain in the like state of servitude. . . . Congress shall pass no laws to prohibit emigrants from bringing their slaves into the republic with them . . . nor shall any slaveholder be allowed to emancipate his or her slave or slaves without the consent of congress. . . . No free person of African descent, either in whole or in part, shall be permitted to reside permanently in the republic.”7

Annexation now became such a contentious issue that President Van Buren (1837–41) felt unable to put it to a vote in Congress. Instead, Texas was left to its own devices as an independent state under its first president (Sam Houston) and recognized only by the United States. Enthusiasm for annexation began to wane even in Texas itself, and the second president (Mirabeau Buonaparte Lamar—Box 2.1) rejected it outright.

President Lamar (1838–41) was a failure in most respects and plunged Texas into financial crisis. However, he did succeed in securing recognition from several European countries. One of these was Great Britain, which saw an opportunity both to phase out slavery in Texas (it had been abolished in British colonies in 1834) as well as gain trading and other privileges. In return, Great Britain—or so it was hoped by Lamar—would guarantee Texan independence against a Mexican revanche.

The prospect of a Texas under British tutelage was not one to appeal to US lawmakers. When the Anglo-Texan treaty was ratified in 1842, therefore, the issue of annexation rapidly moved up the US agenda. By this time Sam Houston, a supporter of annexation, was once again president of Texas. However, President John Tyler (1841–45) still had some work to do in Washington, DC, to overcome the opposition of abolitionists.

This proved more difficult than expected and, just before the end of his presidential term, he had to resort to the highly dubious mechanism of a joint resolution of Congress, requiring only a simple majority of both houses, to secure what he wanted. The offer of annexation was then dispatched to Texas, where it was unanimously accepted in September 1845.

BOX 2.1

MIRABEAU BUONAPARTE LAMAR (1798–1859)

Mirabeau Buonaparte Lamar was born in Georgia in 1798. A firm believer in slavery, he arrived in Texas just before the War of Independence, in which he acquitted himself bravely at the battle of San Jacinto. This brought him to the attention of Sam Houston and subsequent high office. At the time he shared Houston’s enthusiasm for annexation.

Houston was not eligible to run in the 1838 Texan presidential elections, when Lamar was one of four candidates. Bizarrely, however, he would soon become the only serious candidate, as his two main rivals died suddenly (one shot himself and the other drowned in the Bay of Galveston). Lamar then received 6,995 votes, while the one remaining candidate received 252.

In his inaugural address he made it clear that he would reverse Houston’s policy of negotiation with the Indians and advocated “the prosecution of an exterminating war upon the warriors which will admit of no compromise and have no termination except in their total extinction and total expulsion.” This was no idle rhetoric, as his forces then destroyed the Cherokees and Caddos in the east, although they failed to defeat the Comanches in the west.

President Lamar also denounced annexation, arguing instead for an independent Texas that would stretch from coast to coast. He failed to win congressional support for a military campaign to achieve this, but at his own expense recruited volunteers to try and seize Santa Fe as a prelude to taking California. The plan was an abject failure, but it helped to shape US territorial ambitions in the Mexican-American War (1846–48).

Lamar’s stewardship of the public finances was a disaster (he was forced to issue “redbacks” with little value) and the republic was saddled with an unsustainable debt at the end of his term. Not surprisingly, therefore, he became once again a supporter of annexation after his term finished. His final reward was a posting to Nicaragua as US ambassador after the fall of William Walker.

Texas would now become part of the Union as a slaveholding state. It was never a territory of the United States, and it was unusual in other respects as well. While other states had largely crushed Native American resistance before joining the Union with the help of the federal army, Texas would spend its first three decades as a state engaged in a bloody war that was genocidal in both intent and outcome. The main resistance came from the Comanches, and the instruments of their destruction were the federal troops under Colonel Ranald S. MacKenzie and the Texas Rangers.8

The loss of Texas was a blow to Mexico, but it should not be exaggerated. Although the Republic of Texas may have had vast territorial ambitions, its effective borders were much smaller than the State of Texas today (Map 4). Its southern border stopped at the Nueces River, south of which lay the Mexican states of Tamaulipas and Coahuila. In the west, the borders were disputed but did not yet stretch—as the Texan government claimed—to the Río Bravo del Norte (Río Grande).9

Mexico was in fact almost as large in size as the United States, even after the loss of Texas in 1836 (Map 5), although its population was much smaller. However, the Mexican economy was still not increasing as a result of damage to the mines during the war of independence and the subsequent political upheavals. Thus, Mexico had to deal with the threat from the north with a shrunken economy that did not generate sufficient resources for defense expenditure on troops and equipment.

Mexico was also stretched militarily. Spain had tried to retake its former colony in 1829, the province of Yucatán had declared independence in the same year that the Republic of Texas was formed, and two years later (in 1838) the French had invaded Vera Cruz. Although Mexico had some successes (the Spanish and French threats were neutralized, and Spain recognized Mexican independence in 1836), all this left Mexico very vulnerable to any hostile American action.

The biggest concern for Mexico was California.10 Although the Adams-Onís Treaty in 1819 had opened a route to the Pacific for the United States through Oregon, by general consent the best harbors were further south and the best of all was San Francisco in California. Adams himself during his presidency (1825–29) had claimed to be the first statesman to raise the question of US ownership of California, but he had in mind acquisition through purchase rather than war.

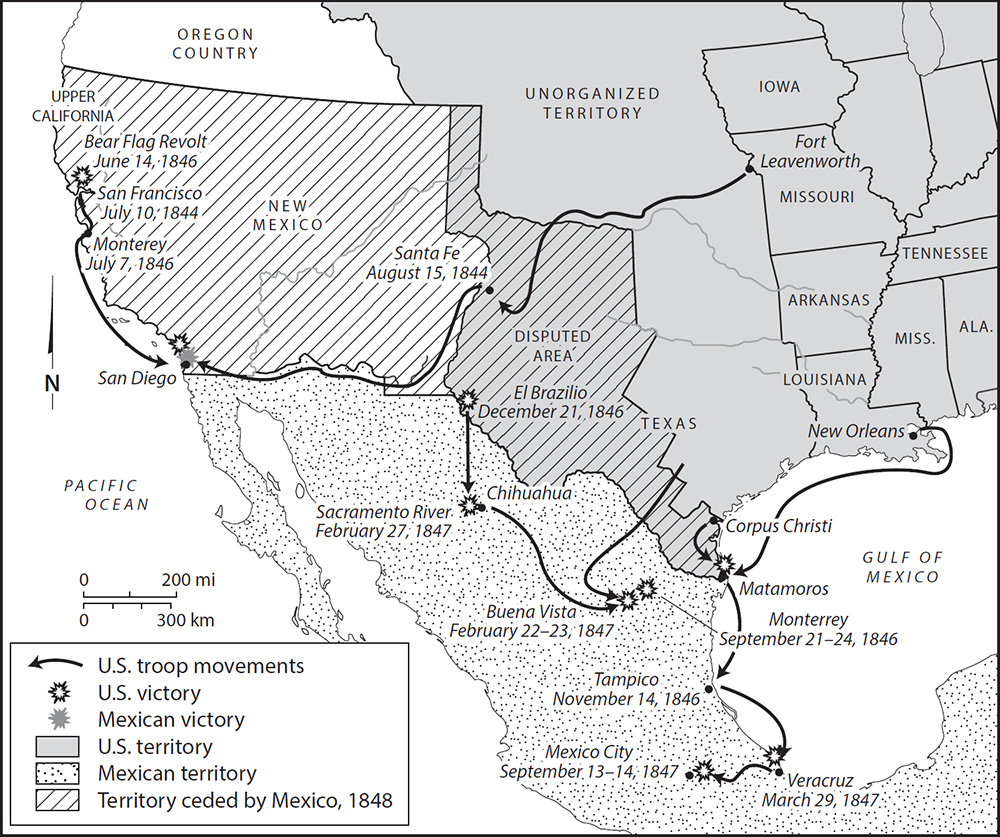

Map 5. Mexico, 1846–48

Those that followed John Quincy Adams were not so circumspect. Secretary of State Daniel Webster had raised the question with Lord Ashburton in 1842 and had been told that the United Kingdom would have no objection. It was Andrew Jackson, however, who was most explicit. When trying to explain to a puzzled Texan government why the US president was reluctant to proceed with annexation, William Wharton, minister of Texas to the United States, summarized Jackson’s view: “General Jackson says that Texas must claim the Californias on the Pacific, in order to paralyze the opposition of the North and East to annexation. . . . He is very earnest and anxious on this point of claiming the Californias, and says we must not consent to less.”11

Similar sentiments were expressed by many others, including Sir George Simpson in 1842, who—when visiting the Swiss adventurer Captain John Sutter—stated that “if he [Sutter] had the talent and courage to make the most of his position, he is not unlikely to render California a second Texas.”12 Sutter, of course, made his mark in another way by confirming the existence of gold in the Sacramento Valley at the end of the Mexican-American War.

Texas had not consolidated a hold over California by the time of annexation despite the best efforts of President Lamar (Box 2.1). It was therefore left to President Polk (1845–49), agitated by an unfounded rumor of British pretensions to California, to put the case more forcibly. Writing to Senator Thomas Hart Benton in October 1845, he cited the Monroe Doctrine and claimed that in his diplomatic policy “I had California and the fine bay of San Francisco as much in view as Oregon.”13

All that Polk—a firm believer in Manifest Destiny (Box 2.2)—needed was a casus belli, and it was not long in coming. The annexation of Texas, confirmed by the Senate in January 1846, could not fail to elicit a response from Mexico. Although the odds were stacked against her, she essentially faced a choice of defeat with honor or capitulation with dishonor and chose the former. When Polk ordered General Zachary Taylor to place his troops south of the Nueces River, it was inevitable that Mexican forces would respond.14

Polk now claimed that the United States had been attacked on American soil, which assumed that the area between the Nueces and the Río Grande was US territory. It was an outrageous claim, but patriotic fervor was enough to secure congressional support for war. A few brave souls, including John Quincy Adams, voted against it, and Abraham Lincoln (who took his seat only after the vote) would make a name for himself with his eight “spot” resolutions calling on Polk to explain exactly where on US soil American forces had been attacked.

US forces advanced on several fronts (Map 5). California, where the Bear Flag Republic had been created in 1846,15 was swiftly occupied with little resistance. Fighting in northern Mexico was fiercer, however, so the Americans allowed Santa Anna to return from exile in the hope that he would quickly sue for peace. When he did not, General Winfield Scott was dispatched to seize the port of Vera Cruz, from which Mexico derived so much of its customs revenue. Scott then proceeded inland and occupied Mexico City.

Mexican casualties were high. However, losses on the US side were also substantial, although most of these were due to illness and poor sanitation. And there were plenty of critics of the war even among the officers themselves. Colonel Ethan Allen Hitchcock, writing in his diary in 1846, claimed, “I have said from the first that the United States are the aggressors. We have outraged the Mexican government and people by an arrogance and presumption that deserve to be punished. For ten years we have been encroaching on Mexico and insulting her. . . . But now, I see, the United States of America, as a people, are undergoing changes in character, and the real status and principles for which our forefathers fought are fast being lost sight of.”16

BOX 2.2

MANIFEST DESTINY

Although the phrase “Manifest Destiny” was believed to have been coined first by John O’Sullivan in 1845, it was perhaps best expressed much earlier in the words of the great Spanish diplomat Luis de Onís himself: “They consider themselves superior to the rest of mankind and look upon their Republic as the only establishment upon earth, founded upon a grand and solid basis, embellished by wisdom, and destined one day to become the most sublime colossus of human power, and the wonder of the universe” (Lowrie, Culture Conflict, 96, quoting Onís’s memoirs).

Onís drew attention to two facets of “Manifest Destiny”: American exceptionalism and the inevitably of expansion. However, he did not mention a third (a belief in racial superiority) that was perhaps best expressed by O’Sullivan himself. In the same article in which he first used the phrase “Manifest Destiny,” he justified taking California from Mexico in the following terms: “The Anglo-Saxon foot is already [1845] on its borders. Already the advance guard of the irresistible army of Anglo-Saxon emigration has begun to pour down upon it, armed with the plough and rifle, and marking its trail with schools and colleges, courts and representative halls, mills and meeting-houses.”

Manifest Destiny was not universally supported nor could it be used to justify empire where the nonwhite population was too large to be “removed.” John Calhoun, for example, denounced Mexican annexation in the Senate in 1848 precisely because it risked diluting the racial “purity” of the United States:

We have never dreamt of incorporating into our Union any but the Caucasian race—the free white race. To incorporate Mexico, would be the very first instance of the kind, of incorporating an Indian race; for more than half of the Mexicans are Indians, and the other is composed chiefly of mixed tribes. I protest against such a union as that! Ours, sir, is the Government of a white race. . . . We are anxious to force free government on all; and I see that it has been urged . . . that it is the mission of this country to spread civil and religious liberty over all the world, and especially over this continent. It is a great mistake.

By late 1847 Mexico was desperate for peace at almost any price. Polk and his secretary of state, James Buchanan, sent a draft treaty to Nicholas Trist, the presidential envoy in Mexico. It called for the cession of all Mexican territory north and east of the Río Grande as well as New Mexico and the two Californias. Anticipating the need for an isthmian route that these cessions would entail, it also called for rights of passage through the Isthmus of Tehuantepec and a payment of $15 million to Mexico.

The United States could easily have forced Mexico to agree, but by a strange twist of fate it did not turn out that way. Trist was recalled by Polk in October 1847 on the grounds that he was untrustworthy, but he chose to ignore the order. He then negotiated a separate treaty, which left out Baja California and the rights of passage through the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. Polk was furious, but chose to accept it anyway with only one change (he removed the clause guaranteeing Mexican land titles in the ceded areas). The Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo, as it was called, was then passed by the Senate in March 1848.

When Polk left office the following year, he might have assumed that the United States had taken all it needed from Mexico. However, territorial cession surfaced again a few years later, when James Gadsden, a railway entrepreneur and US minister to Mexico, persuaded Jefferson Davis, secretary of war in the government of President Franklin Pierce (1853–57), that the best route for a railroad between Charleston and California lay south of the border. By then Santa Anna was back in power and in desperate need of funds. The Gadsden Purchase, as it became known, was duly carried out in December 1853 in return for $10 million.

The prospect of acquiring additional territory from Mexico had raised questions about slavery as soon as the war started. In August 1846 David Wilmot, a Democrat, added a clause to an appropriations bill to the effect that slavery would not be permitted in any of the land taken from the southern neighbor. The Wilmot “proviso” did not pass, but it left on the table an unanswered question: Would slavery be permitted in the new territories?

The answer came four years later in the Compromise of 1850. Drafted by Henry Clay, this consisted of eight resolutions. It excluded slavery from California, but any other territories formed out of the Mexican acquisitions would be free to decide what to do. It ended the slave trade from neighboring states into the District of Columbia, but introduced a much tougher fugitive slave law for the restitution of “persons bound to service or labor, in any State, who may escape into any other State or Territory of this Union.”17

Slavery was excluded from California because it was impossible to delay a decision (events had moved so fast), and allowing slavery there would have been politically difficult. The Russians had dismantled the last of their forts in 1842, when the non-Indian population of Alta California was around 5,000 and that of US settlers as few as 360. The discovery of gold in January 1848 then led to mass immigration, and the non-Indian population had jumped to 107,000 by January 1850.18

This was large enough for California to jump to statehood without first becoming a US territory, and it duly entered the Union in September 1850. Subjugation of the Indian population was therefore conducted after statehood rather than before, with a leading role played by the white settlers themselves rather than federal troops.19 This also happened in Texas, and in both cases the consequences were especially tragic for the Native Americans.

The Spanish had only settled Alta California in the late eighteenth century. As a result, it still had a large Indian population. This was soon reduced by disease as a result of contact with the Europeans, but as late as 1849 it was still estimated at 100,000. By 1860, however, it had collapsed to 35,000, and by 1890 it had fallen to 18,000. This time disease was not the main factor.

The rapid immigration of settlers to California after the Mexican-American War led to competition for resources leading to starvation in many cases. The state legislature passed an antivagrancy law for the indenture of “loitering and orphaned” Indians that was little better than slavery (boys and girls as young as twelve were taken). Settlers took matters into their own hands and carried out numerous massacres. It is difficult to disagree with Russell Thornton’s assessment that “California is the one place in the United States where few would dispute that a genocide of Native Americans occurred.”20

The Compromise of 1850 not only admitted California to the Union as a state but also established two new territories: New Mexico and Utah (with boundaries much bigger than these states today).21 Expectations were high that the territories would soon enter the Union as states. New Mexico in particular, with its capital at Santa Fe, had a relatively large non-Indian population, although Utah’s population—where the Mormons under Brigham Young had established themselves—was smaller.

These expectations had to be rapidly changed. Even before the territory of New Mexico was formed, the governor (appointed by the US military) had been murdered by an alliance of Mexicans and Indians. There then followed a series of wars against the Apaches in particular that started in 1849 and did not end until the surrender of Geronimo in 1886. Even then, sporadic fighting continued until Indian resistance was finally broken in 1906.22

Statehood therefore took decades to achieve for some parts of the territories acquired from Mexico. After California, Nevada was the first to become a state. It was separated from Utah Territory in 1861, following the discovery of silver, and joined the Union after a mere three years, as silver was such a vital commodity in the Civil War. Utah, whose first governor had been Brigham Young himself, was the second although it had to wait until 1896 in view of the controversies surrounding the Mormon religion.23

New Mexico took even longer as a result, above all, of the Indian Wars. The Confederacy in 1861 established Arizona Territory in the south, to which the Union responded in 1863 by creating its own Arizona Territory and splitting off the western half of New Mexico. There was then a long hiatus until Arizona and New Mexico joined the Union in 1912. By this time they had spent sixty-two years under territorial government, during which they were effectively US colonies. Indeed, when Arizonan Barry Goldwater declared his presidential candidacy, his opponents ruled that he was not eligible to run as he had been born outside the United States.24

The Gadsden Purchase had given the US government the rights of passage across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec denied by the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo. However, the new treaty left the proposed railroad under the control of Mexico. Much more promising for US ambitions to have exclusive control of an isthmian route, therefore, was the Bidlack-Mallarino Treaty between the United States and New Granada (today Colombia)25 signed in 1846 and ratified two years later.

This treaty not only gave guarantees “that the right of way or transit across the Isthmus of Panama, upon any modes of communication that now exist or that may be hereafter constructed, shall be open and free to the government and citizens of the United States,” but also committed the United States to maintain the “perfect neutrality” of the isthmus and to guarantee “the rights of sovereignty and property which New Granada has and possesses over the said territory.”26

The prospects for building a canal across the isthmus did not look good at the time in view of the engineering obstacles, but a railway was another matter. A private US company was established for this purpose, work began in 1852, and it was completed in 1855. This was too late to take advantage of those seeking to reach California in time for the gold rush, but it was still a very profitable operation from the start.

The US government was now responsible under the terms of the 1846 treaty for protecting the route in the event of any local disturbance. This was not uncommon in nineteenth-century Colombia and the United States would find itself embroiled in numerous political disputes before the century ended.

The first year in which US troops were landed in Panama was 1856. This was followed by military interventions in 1860, 1865, 1868, 1873, 1885, and 1895. And these interventions could have major implications. In 1885, for example, US troops put down a rebellion by members of the Liberal Party that restored the Conservatives to power and led to the harsh dictatorship of Rafael Núñez.

The 1846 treaty had therefore converted the province of Panama into a US protectorate. This suited the purposes of President Polk and his immediate successors, but it was President Lincoln (1861–65) who came closest to creating a US colony in Panama in the nineteenth century. In his address to leaders of the free blacks at the White House in August 1862, he said, “But for your race among us there could not be war, although many men engaged on either side do not care for you one way or the other. . . . It is better for us both, therefore, to be separated. . . . The place I am thinking about having for a colony is in Central America. . . . The particular place I have in view is to be a great highway from the Atlantic or Caribbean Sea to the Pacific Ocean, and this particular place has all the advantages for a colony.”27

Lincoln did not mention the isthmus by name, but the “particular place” he had in mind was western Panama, where the Chiriqui Improvement Company had been established. He had already instructed his secretary of the interior to purchase two million acres from the US-controlled company established there, and he had secured $600,000 from Congress for his colonization scheme.

It is perhaps fortunate for Lincoln’s future reputation that the scheme never took off. Most black leaders, including Frederick Douglass, opposed it as racist. In addition, Lincoln had failed to take into account that he would need a treaty with Colombia if the scheme were to go ahead. In the end, therefore, the idea was dropped, although Lincoln did finance a colonization scheme for free blacks in Haiti that was a miserable failure.28

The 1846 treaty required the United States to guarantee the “perfect neutrality” of the isthmus, but it had not explicitly authorized the use of force. To resolve this uncertainty, successive administrations from President Pierce onward negotiated a series of treaties with the Colombian authorities. Yet none of these were ratified, as a result of reservations either by the Colombian or US senates (the former argued that the treaty in question gave away too much, while the latter claimed that it ceded too little).

The first of these treaties set the tone. Following a riot in Panama in 1856 that caused much loss of life and property, the US negotiators were able to persuade the Colombian executive to sign a treaty which

provided that the United States government should buy, for cash, all New Granada’s reserved rights in the railroad, and also secure control of strategic islands in the harbors at either terminus, for naval stations. Then, in order to provide for the neutralization of the route, in fact as well as in theory, [the negotiators] also proposed that a belt of land twenty miles broad, lying on both sides of the railway line, and extending from sea to sea, be carved out of the territory of New Granada and handed over to the jurisdiction of two free municipalities to be established in Aspinwall [modern Colón] and Panama [City].29

This treaty, if implemented, would have undoubtedly created a US colony on the isthmus, so it is not surprising that the Colombian Senate baulked at the idea. Yet the next treaty in 1869 went even further, as it would have given the United States “the sole right of constructing a canal” and allowed the nation “to employ their military forces if the occasion should arise.” When in another treaty the following year the Colombian negotiators stripped out a reference to the use of force, it was the US Congress that refused to ratify. The last of these treaties was in 1902, which was unanimously rejected by the Colombian Senate on the grounds that the hundred years proposed for US control of the proposed canal was too long.

Frustrated by its inability to conclude a deal with the United States that would have led to the construction of a canal, the Colombian government was very receptive to a French proposal put forward in 1876 by Ferdinand de Lesseps. Flushed with his success in building the Suez Canal, Lesseps expected to have no trouble in raising the initial funds. However, he needed to avoid outright opposition from the United States if the scheme was to have a reasonable chance of success.

In this he was to be disappointed. In a meeting at the White House with Lesseps, President Rutherford B. Hayes (1877–81) was very candid:

I deem it proper to state briefly my opinion as to the policy of the United States with respect to the construction of an inter-oceanic canal by any route across the American Isthmus. The policy of this country is a canal under American control. The United States cannot consent to the surrender of this control to any European powers. If existing treaties between the United States and other nations, or if the rights of sovereignty or property of other nations stand in the way of this policy—a contingency which is not apprehended—suitable steps should be taken by just and liberal negotiations to promote and establish the American policy on this subject, consistently with the rights of the nations to be affected by it.30

Despite this, the project went ahead in 1882 with the subsequent participation of Philippe Bunau-Varilla (Box 2.3). Fortunately for the American government, however, Lesseps misjudged the engineering complexities of building the canal, exhausted the funds in inflated expenses, and was soon unable to secure additional loans. The French canal scheme then collapsed in 1888 after the death of thousands of workers (only twenty miles of the route was completed).

The collapse of the French scheme confirmed the view of those in the United States who had always regarded the Nicaraguan route as superior on financial and engineering grounds. However, progress toward the construction of a canal through Nicaragua was blocked in the 1890s (see below). Thus, when Theodore Roosevelt became president in September 1901,31 US attention was once again focused on Panama. When a “revolution” took place on the isthmus on November 3, 1903, the leaders proclaimed Panama’s independence and asked for US recognition. This was given three days later, US warships were dispatched to both sides of the isthmus, and Colombian troops were prevented from reaching Panama City.32

Converting “independent” Panama into a US protectorate was now a simple matter since the leaders of the 1903 revolt owed their victory to US support. Two weeks after independence, a treaty was signed giving America sovereignty in perpetuity over a new Canal Zone (ten miles wide across the center of the country) and the right to intervene in Panama City and Colón (both outside the zone) to maintain public order.33 Subsequently, Panama placed the United States in charge of collecting customs duties (the largest source of government revenue), with the US dollar as the country’s currency.

Despite these extraordinary powers, the United States often had difficulty in mediating disputes between local politicians. America at first favored the Conservative faction and one of their leaders, Manuel Amador, was installed as president in 1904. The Liberals were then dissatisfied and sought US support for a change of government. These sometimes violent struggles among the political elites continued for nearly three decades. However, there was never any threat to US strategic interests, as all participants understood very clearly the rules of the imperial game.

Following a coup in 1931, Panamanian politics changed abruptly. The revolt brought to power Harmodio Arias, who—with his brother Arnulfo—would dominate the political scene for decades. Indeed, the last time one of the brothers occupied the presidency was as late as 1968. The family would also achieve notoriety outside Panama, while one of Harmodio’s sons (Roberto) married the brilliant British ballerina Margot Fonteyn in 1955.34

BOX 2.3

PHILIPPE BUNAU-VARILLA (“MR. CANAL”)

President Theodore Roosevelt (1901–9) would have built an isthmian canal during his tenure under almost any circumstances. However, his choice of Panama over Nicaragua was greatly influenced by Philippe Bunau-Varilla, a Frenchman born in Paris in 1859. Bunau-Varilla went to Panama in 1884 to work for Ferdinand de Lesseps in the Panama Canal Company. The company collapsed in 1888, but another firm—the New Panama Canal Company—was established in 1894 with Bunau-Varilla as an investor.

As late as 1901 the US government still favored Nicaragua as the route for a canal. Bunau-Varilla, however, was determined that the US government should choose Panama. He campaigned tirelessly through many states and even sent to all US senators postage stamps of Mount Momotombo in Nicaragua erupting. He hoped in this way to demonstrate the riskiness of the Nicaraguan route.

These efforts paid off, as the Senate in June 1902 passed the Spooner Act under which the New Panama Canal Company would be purchased for $40 million if Colombia would agree to a treaty allowing for a canal to be built under exclusive US control. This treaty was signed, but Colombia did not ratify it. Bunau-Varilla therefore provided funds to dissidents in Panama and persuaded them that they could count on US recognition if they led an uprising against Colombia. He even brought them to Washington, DC, and presented them with a draft constitution (his flag design, however, was later rejected). The revolt then took place on November 3, 1903.

As soon as the Roosevelt administration recognized the independence of Panama, Bunau-Varilla had himself declared ambassador of Panama to the United States. He then negotiated in a few days the infamous treaty that bears his name (the Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty). This gave the United States everything that it desired. No Panamanian signed this treaty, but the leaders of the revolt felt they had no choice but to ratify it on December 2, 1903. Bunau-Varilla later returned to France, where he fought in the First World War and lost a leg at the Battle of Verdun. He died in 1940, having campaigned to the end to convert the canal from a system of locks to a sea-level waterway.

The Arias brothers were no anti-imperialist radicals, but they were nationalists and sought to build a Panamanian identity. This inevitably involved many clashes with the United States. Their main target was the one-sided 1903 treaty. Their efforts, helped by the launch of the Good Neighbor policy of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1933–45),35 eventually bore fruit in 1936 with a renegotiation of the treaty in which the United States gave up the right to intervene unilaterally in Panamanian affairs and to pay a larger annual subvention for use of the canal.36

The treaty revisions did not end Panama’s status as a protectorate, as the United States did not give up its military bases or its fiscal and monetary control of the country. And, of course, it also kept the Panama Canal Zone as a US territory. Nor did it cease to intervene in local affairs since the treaty said nothing about favoring one faction over another. And without US support, no Panamanian leader could survive for long.

This was made abundantly clear a few years after the new treaty was ratified when Arnulfo Arias became president in October 1940. Since he was convinced Germany would win the Second World War (he had been Panama’s ambassador to both Adolf Hitler’s Germany and Benito Mussolini’s Italy, and had fascist sympathies), he became increasingly suspect in US eyes. His unauthorized departure as president from the country in 1941 became the opportunity for him to be replaced with a more pliant ruler.

No US troops were used, and no articles of the new American-Panamanian treaty had been broken. Instead, the next president had consulted with the chief of civil intelligence in the Canal Zone who confirmed that the United States would be happy to see Arnulfo Arias removed from office. This information was all that was needed for the plotters and, indeed, for those who had supported Arias up to that moment.

Despite the treaty revisions, the United States intervened in Panama and the Canal Zone on numerous occasions—the last time being the military invasion in 1989. By then, however, the US Senate had ratified the 1977 Canal Treaties under which the Canal Zone would cease to exist on October 1, 1979, making it no longer a US territory, and a Panama Canal Commission would gradually take control of the operation of the canal by December 31, 1999.37 At that point the Panamanian protectorate that had begun 150 years before finally came to an end.

Although the isthmian canal was eventually built in Panama, there had been an international consensus throughout almost all the nineteenth century that a canal through Nicaragua offered the best prospects. As soon as the Spanish empire ended, therefore, there was competition among the imperial powers to establish control over what would become the Republic of Nicaragua.38 The US government was the first of these powers to recognize the United Provinces of Central America39 after the new country declared its independence from Mexico and a US canal company was formed in 1826.40

Unfortunately for the United States, the British were already firmly ensconced in the region. The Belize Settlement was being transformed into a British colony, the Bay Islands off the northern coast of Honduras were occupied in 1842, and Great Britain was rebuilding its protectorate over Mosquitia—the eastern portion of Nicaragua and Honduras.41 The British government was even laying claim to the coast of Costa Rica and an island off Panama, potentially giving it control over all Caribbean points of entry to an isthmian canal.

What followed was therefore an intense rivalry between the old (UK) and new (US) imperial powers for hegemony over Nicaragua, in which two diplomats in Central America played a leading part: Ephraim Squier for the United States and Frederick Chatfield for Great Britain. However, the struggle was orchestrated from London and Washington, DC, becoming increasingly bitter and dangerous.

All surveys had agreed that the best route for the Nicaraguan canal starting on the Caribbean side involved navigation up the Río San Juan to the Lago de Nicaragua. This river, which marks the border between Costa Rica and Nicaragua for most of its length, reaches the sea at the port of San Juan. Since the town lay within the territory claimed by Great Britain as part of the Mosquitia protectorate, the British government seized it in January 1848, expelled the Nicaraguan commandant, and changed the name to Greytown.42

The Nicaraguan government protested in vain. However, a year later—under the stimulus of the Californian gold rush—it signed an agreement with Cornelius Vanderbilt establishing a Companía de Tránsito de Nicaragua (known in English as the Accessory Transit Company) to ferry people and goods across the isthmus. Since the route taken passed through San Juan, the US government now had even more reason to challenge what was seen as a breach by the United Kingdom of the Monroe Doctrine.

Ephraim Squier acted swiftly. First, he secured a treaty with the Nicaraguan government for construction of a canal by Vanderbilt’s company under exclusive US control. This provided land for US colonization across the isthmus and a monopoly for the company of steam navigation on Nicaragua’s lakes and rivers. Second, he signed a treaty with the Honduran government that ceded Tigre Island in the Gulf of Fonseca, where the canal was expected to enter the Pacific, as well as land for fortifications on the Honduran coast.43

Squier’s actions were designed to create US protectorates in both Honduras and Nicaragua, and they threatened to stymie British plans for building a canal since the United States would have been left in control of the waters guarding the entrance to a canal on the Pacific side. The British Navy therefore seized Tigre Island before the United States could occupy it and refused to back down when the United States threatened war.

It was time for cooler heads, and the result was the Clayton-Bulwer Treaty of 1850. This treaty recognized that neither the United Kingdom nor the United States was strong enough to impose its will on the other in Central America and that neither would seek to establish exclusive control over a ship canal “which may be constructed between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans by way of the river San Juan de Nicaragua and either or both of the lakes of Nicaragua or Managua.” 44

The Clayton-Bulwer Treaty was seen at the time as a triumph for US diplomacy and a defeat for the British. However, the wording was highly ambiguous and would soon cause a great deal of friction. Furthermore, as the US government became increasingly committed to a canal through Nicaragua under its exclusive control, it looked for ways to abrogate or revise the treaty. The British stubbornly refused to comply on the grounds that the treaty had been signed and ratified in good faith by both parties.

The US government therefore turned its attention to Nicaragua itself. However, the embarrassing Walker episode in the 1850s (Box 2.4) created a poisonous legacy for the United States that has still not entirely drained. The best that US diplomacy could manage, therefore, was the 1868 Dickinson-Ayon Treaty.45

The treaty gave the United States much that it desired, but it could make no mention of “exclusive” control in view of the wording of the Clayton-Bulwer Treaty. The sense of frustration deepened with the publication in 1890 of Alfred Thayer Mahan’s The Influence of Sea Power upon History, which was widely interpreted as presenting an overwhelming case for an interoceanic canal to enhance US naval power. And, of course, that canal had to be controlled exclusively by the United States itself.

It was not until 1901 that America was finally able to persuade the British to abrogate the 1850 treaty and sign a new one giving the United States exclusive control over any isthmian canal. This was the Hay-Pauncefote Treaty. The British resisted as long as possible, but eventually accepted the inevitable and ratified the treaty.

BOX 2.4

WILLIAM WALKER (“THE GREY-EYED MAN OF DESTINY”)

William Walker was born in Tennessee and had a distinguished education. A strong believer in Manifest Destiny, he was convinced that the decision not to push the US boundaries further south after the war with Mexico was a mistake. He therefore led a filibuster to Baja California in 1853, had himself declared president of the Republic of Sonora (in which he included Baja California), and legalized slavery.

After he was expelled by the Mexican Army, he accepted an invitation from the Liberals in Nicaragua to help them in their civil war with the Conservatives. He arrived in 1855 and the Liberals took power the following year. Walker was at first content with the role of commander in chief, but by July 1856 he had made himself president of Nicaragua through a fraudulent election.

His government legalized slavery, made English the official language, and planned to take over all Central America. These actions ensured the opposition not only of many in Nicaragua but also the governments of other Central American countries. In addition, he foolishly made an enemy of Cornelius Vanderbilt, whose Accessory Transit Company was a major power in Nicaragua. The combination of all these forces was sufficient to defeat Walker militarily in May 1857.

All this could have been dismissed as opera buffa were it not for the ambiguous relationship Walker enjoyed with the United States. President Franklin Pierce (1804–69) gave diplomatic recognition to Walker’s Nicaragua in 1856. When he surrendered to the US Navy in 1857, he was not handed back to the Nicaraguan authorities. When he was charged in New Orleans in 1858 with breaking US neutrality laws, he was acquitted. When he returned to Nicaragua in 1859, he was arrested by the US Navy and then released on the orders of the administration of President James Buchanan (1857–61).

Walker made a third attempt to reach Nicaragua. This time he landed at Trujillo in Honduras, where locals turned him over to the British Navy. They in turn handed him to the Honduran government, who ordered him to be shot in September 1860.

By this time President José Santos Zelaya (1893–1909) was in power in Nicaragua and he had every reason to assume that the canal would now be built in his country. Not only were all the US engineering studies, interoceanic commissions, and congressional reports pointing in that direction, but Zelaya himself in 1894 had also incorporated Mosquitia into Nicaragua and ended the threat of British intervention.46

The news that the canal would be built through Panama was, therefore, not well received by President Zelaya. Not surprisingly, he tried to keep his options open and turned to Germany and Japan to initiate negotiations on financing an interoceanic canal through Nicaragua that would have posed a considerable threat to the commercial success of the Panama Canal if it had been built. It would also have given a potential enemy a big stake in the region.

When news of these arrangements reached Washington, DC, it meant that a red line had been crossed. Plans were made to remove Zelaya, and a local “revolution” would provide the perfect excuse. At the end of 1909, US troops briefly landed on the Caribbean coast and a familiar pattern was repeated. A customs receivership was established in 1911, which continued until 1947. Loans to European creditors were replaced with loans to US bankers. A “loyal” politician was maneuvered into the presidency. A US protectorate over Nicaragua, which had been threatening since the 1840s, had finally become a reality.47

This exercise in US imperialism had not, however, taken account of the deep divisions in Nicaraguan society between Conservatives and Liberals. With Zelaya (a Liberal) in exile, the leaders of both parties understood perfectly the unwritten bargain between the United States and a protectorate. However, they could not work with each other. Thus, political instability reached a high level, and the US Marines returned in 1912. This time, it would be a long stay.48

One of the first acts of the US occupation was to prepare the ground for a treaty that would settle the canal question once and for all. This was the Bryan-Chamorro Treaty of 1916, which gave the United States rights to any canal built in Nicaragua in perpetuity and a renewable ninety-nine-year option to establish a naval base in the Gulf of Fonseca. The United States, of course, now had no intention of building such a canal, but the treaty ensured that no other country could do so.49

A series of pliant Conservative leaders lulled the occupying force into a sense of complacency. Indeed, one—Adolfo Díaz—had even proposed annexation by the United States in 1924. When the marines left in 1925, however, it led to a period of deep political instability and the troops returned the following year. Henry Stimson, US secretary of state, would then negotiate a pact with both Nicaraguan parties that bore a striking similarity to those in Haiti and the Dominican Republic (see Chapter 4). In particular, it led to the formation of an allegedly nonpartisan national guard.50

Resistance to the US-brokered pact was led by Augusto César Sandino, an army officer and a nationalist. The guerrilla forces had inferior weapons, but they could not be defeated. Sandino and his followers survived in the mountains until the last US troops had left in 1933. By this time, the United States had chosen as the head of the national guard a young officer called Anastasio Somoza, who would trick Sandino into accepting negotiations in February 1934 and then assassinate him. Despite this, or perhaps because of this, Somoza remained a firm favorite of US officials in the country.51

His “reward” was to be the presidency of Nicaragua, which he held directly and indirectly until his own assassination in 1956. Somoza was a consummate player of the imperial game and knew exactly what he needed to do to retain US support. Indeed, on one of his official visits to Washington, DC, he allegedly provoked the comment from President Franklin Roosevelt that “he may be a son of a bitch, but he’s our son of a bitch.”52

Anastasio Somoza was followed by his two sons, the first of whom died in 1963. The second son ruled until 1979 as head of a regime that became increasingly brutal and eventually lost US support. He was overthrown by the Sandinistas in a revolution that subsequently disappointed many of its supporters, although it did end the country’s status as a US client state.53

Control of Nicaragua and Panama for most of the twentieth century met US security needs in Central America. However, imperialist countries are always sensitive to the need to neutralize any threat that might arise to their colonies, protectorates, or client states from neighboring countries. In particular, the United States was anxious to avoid any government coming to power that could threaten its vital strategic interests in the region. Additional strategies were therefore needed for the rest of Central America.

Following a peace conference hosted in Washington, DC, by the United States, the Central American states established in 1907 a Central American Court of Justice, with its headquarters in Costa Rica. The expectation was that the court would uphold the rule of law and therefore protect US interests. It started well, but the United States lost interest when the Court ruled that Nicaragua was acting illegally when it granted America a ninety-nine-year lease on the Corn Islands in the Caribbean.54

The United States then called another conference, which led in 1923 to the Central American International Tribunal, with its headquarters in Washington, DC, and fifteen judges appointed by the US government. The tribunal, which operated for nearly a decade, was an early example of US imperial power relying on control of institutions.55

US imperial control in Central America was more complete than in any other part of the world. Yet, apart from the Panama Canal Zone, it did not depend on colonies. Control was exercised through protectorates in Nicaragua and Panama and client states elsewhere (Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras). In 1920, for example, Franklin Roosevelt—at the time a vice presidential nominee—could boast that the United States controlled the votes of all six Central American countries in the proposed League of Nations.56