One of the more commonly held myths about the US empire is that it did not go “offshore” until after the Spanish-American War in 1898. Long before then, however, American imperialism had penetrated different parts of the world outside the western hemisphere. This chapter looks at the process by which American empire was extended to Africa and the Pacific.

There was no uniform pattern by which US influence spread and imperial acquisitions ranged from territories (i.e., colonies) to protectorates and—in the case of China—treaty port concessions. Yet this was no different from what happened in European empires. British India, for example, was ruled by a private company (the East India Company) until 1858 and yet only a pedant would argue that it was not part of the British Empire before then.

US interest in the Pacific was awakened by the Meriwether Lewis and William Clark expedition at the start of the nineteenth century, but it was not until the Adams-Onís Treaty of 1819 gave the country a foothold on the Pacific shore that anything significant could be done about it. From that point onward, the United States was determined to dislodge as far as possible other imperial powers along the coast. When Mexico in 1821 replaced imperial Spain as the sovereign power south of Oregon Country, the same applied to her.

Spain’s trade with China, routed through Acapulco in Mexico and Manila in the Philippines, had long excited the interest of other empires. It was no different with the United States. A Pacific coastline gave America its chance to gain access to the fabled Chinese market, with its millions of consumers, as long as it was not excluded either by China itself or by other imperial powers. China and the surrounding countries were also a magnet for US missionaries seeking to spread the message of Christianity.

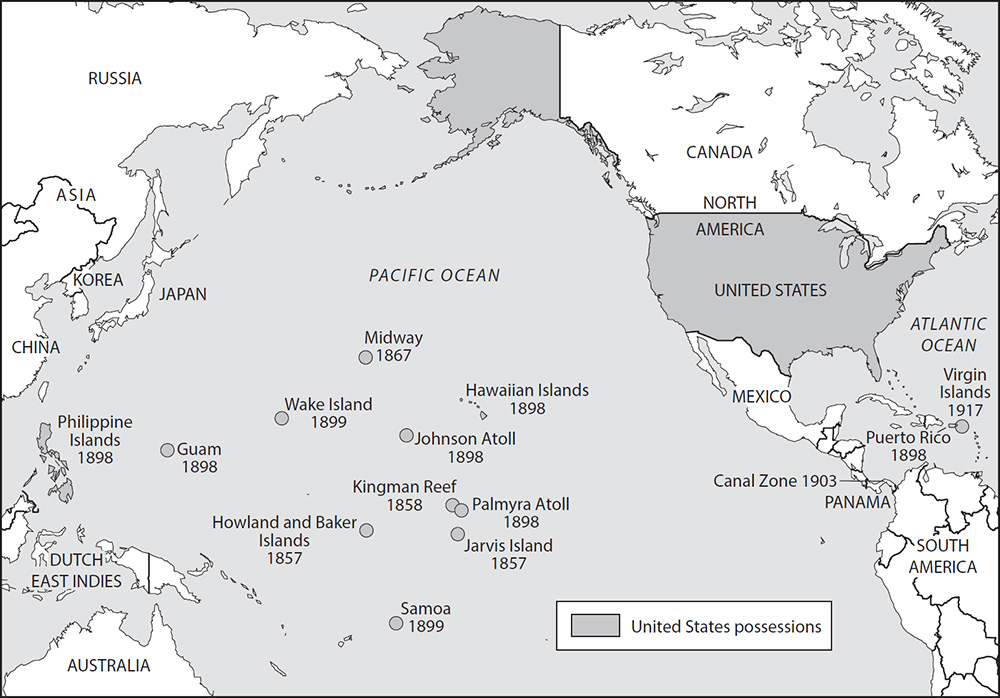

Even before Commodore Matthew Perry in 1854 sailed into Edo (Tokyo) Harbor, the United States had demonstrated its commercial and diplomatic prowess in the region. It had also shown the skill of its navy. Yet the opening of the Japanese market as well as footholds in China required a more strategic approach to the Pacific. Using the Guano Islands Act in 1856 as a first step, a string of islands was secured across the Pacific that could be used by US ships.

The territorial presence included bigger islands as well. Hawaii was brought into the US sphere of influence as a protectorate long before annexation in 1898, while the United States almost went to war with Great Britain and Germany in order to gain control of part of Samoa. And Alaska, of course, was purchased from Russia in 1867, leaving the United States in control of the whole North American Pacific coastline except for British Columbia in Canada.

The US empire was therefore well established in the region before the Spanish-American War. However, success in that war brought new imperial possessions in the Pacific—notably the Philippines and Guam (one of the Mariana Islands). The other (northern) Mariana Islands, on the other hand, were sold by Spain to Germany in 1899, as the United States had no use for them at the time.

When Germany was defeated in the First World War, it might have been expected that the Northern Marianas and other German-controlled islands would be claimed by the United States. However, the islands were taken by Japan as part of the spoils of war. It was not until the end of the Second World War that the Japanese-controlled islands were formed into the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands (TTPI) and placed under US control by the United Nations (the organization that replaced the League of Nations).

With the occupation of Japan and part of the Korean Peninsula, the United States then extended its formidable imperial presence in the Pacific even further. At the same time, although the Philippines may have been formally decolonized in 1946, the independence treaty—together with huge naval and air bases—ensured that the country would remain inside the US sphere of influence as a protectorate. And when the TTPI ended in the 1980s, some islands simply became US protectorates, while the Northern Mariana Islands chose to remain a US colony with a similar status to Puerto Rico.

The empire that the United States built in the Pacific in the nineteenth century demonstrated that America could even then match the imperial ambitions of any other country. And as soon as the Spanish-American War concluded, the European powers began to recognize the United States as “first among equals” in the regional struggle for power and influence. The two world wars then left the United States in a hegemonic position, untroubled by the remaining European presence and yet to face serious competition from China.

Africa never excited the same imperial interest in the United States as the Pacific, but it would be wrong to say there was none. The Barbary Wars, it is true, were fought by the United States in self-defense and were therefore not imperial conflicts. However, the end of the legal slave trade in 1808 and the growing numbers of free blacks in the United States drove interest in African colonization. This culminated in the establishment of the American Colonization Society (ACS) at the end of 1816.

The ACS, a private organization, is best known for the foundation of a series of colonies in West Africa that eventually came together to form the Commonwealth of Liberia. However, these efforts would never have prospered without the support of the US federal government. Thus, right from the start Liberia can be considered an American colony. Indeed, it was a form of settler colonialism very similar to what was happening in the US mainland territories, though with the settlers (Libero Americans) being black rather than white.

Liberia declared “independence” in 1847. However, a treaty of recognition, delayed until 1862 because of southern opposition, gave the United States the right to intervene under certain circumstances. By 1912 Liberia had formally become a US protectorate with a customs receivership and various other restrictions on national sovereignty. Even when the receivership ended, Liberia remained in the US sphere of influence as a client state, with the US dollar as its currency and one of the most pro-American foreign policy regimes in the world.

The United States did not participate in the “scramble for Africa” after the Berlin Conference (1884–85) organized by Chancellor Otto von Bismarck of Germany. Yet it was invited to the conference and sent a strong delegation to sit alongside the other imperial powers (Box 3.1). The delegates, including Henry Morton Stanley, then backed the plans of King Leopold of Belgium for a Congo Free State in the belief that this—rather than formal colonies—would secure US interests on the subcontinent. It was not until after the Second World War that the United States would raise its voice against European imperialism in Africa, and even then it would be highly selective.

When the first US census was held in 1790, the category “all other free persons” contained around fifty thousand people (just over 1 percent of the population). These free blacks were not regarded as the social or political equals of their white counterparts in the nonslave states and were treated with deep suspicion in the slave ones. As their numbers increased, both black and white opinion divided between those who favored integration and those who championed the establishments of colonies to which the free blacks would be encouraged to move.

Thomas Jefferson was among the most vocal who favored colonies. Indeed, he had promoted the idea as early as 1777 when drafting a new constitution for Virginia.1 Later, as president, he tried to persuade the British government to allow freed slaves to move to the colony of Sierra Leone in West Africa (the request was rejected). After the abolition of the slave trade in 1808, however, the matter became more urgent for the US government as slaves intercepted on the high seas needed to be sent somewhere other than the US mainland.

The response was the ACS, founded in December 1816. Its members included white abolitionists, Christian missionaries, and some free blacks. However, its most powerful members were slaveholders and those who supported the “peculiar institution.” Indeed, Henry Clay (chairman of the meeting that established the ACS) made clear that no attempt was being made “to touch or agitate in the slightest degree, a delicate question, connected with another portion of the colored population of this country. It was not proposed to deliberate upon or consider at all, any question of emancipation, or that which was connected with the abolition of slavery. It was upon that condition alone he was sure, that many gentlemen from the South and West, whom he saw present, had attended, or could be expected to cooperate. It was upon that condition alone that he himself had attended.”2

Subject to these conditions, the ACS was formally established in 1817 with Bushrod Washington3 as president and held its first meeting in the halls of Congress. Although it was always a private organization, it enjoyed government support at the highest levels. Indeed, US naval officers accompanied a small group of colonists in 1821 and secured the first land cessions from the local chiefs in return for “Six muskets, one box Beads, two hogsheads Tobacco, one cask Gunpowder, six bars Iron, ten iron Pots, one dozen Knives and Forks, one dozen Spoons, six pieces blue Baft, four Hats, three Coats, three pair Shoes, one box Pipes, one keg Nails, twenty Looking-glasses, three pieces Handkerchiefs, three pieces Calico, three Canes, four Umbrellas, one box Soap, one barrel Rum.” 4

The US naval officers, acting on behalf of the ACS, had used the same techniques as the British settlers in North America two centuries earlier to secure territory, and their methods would be just as dubious. The tribes people never accepted this, nor subsequent land cessions, and there would be conflict between the Libero Americans, as they came to be called, and the indigenous population for more than a century.

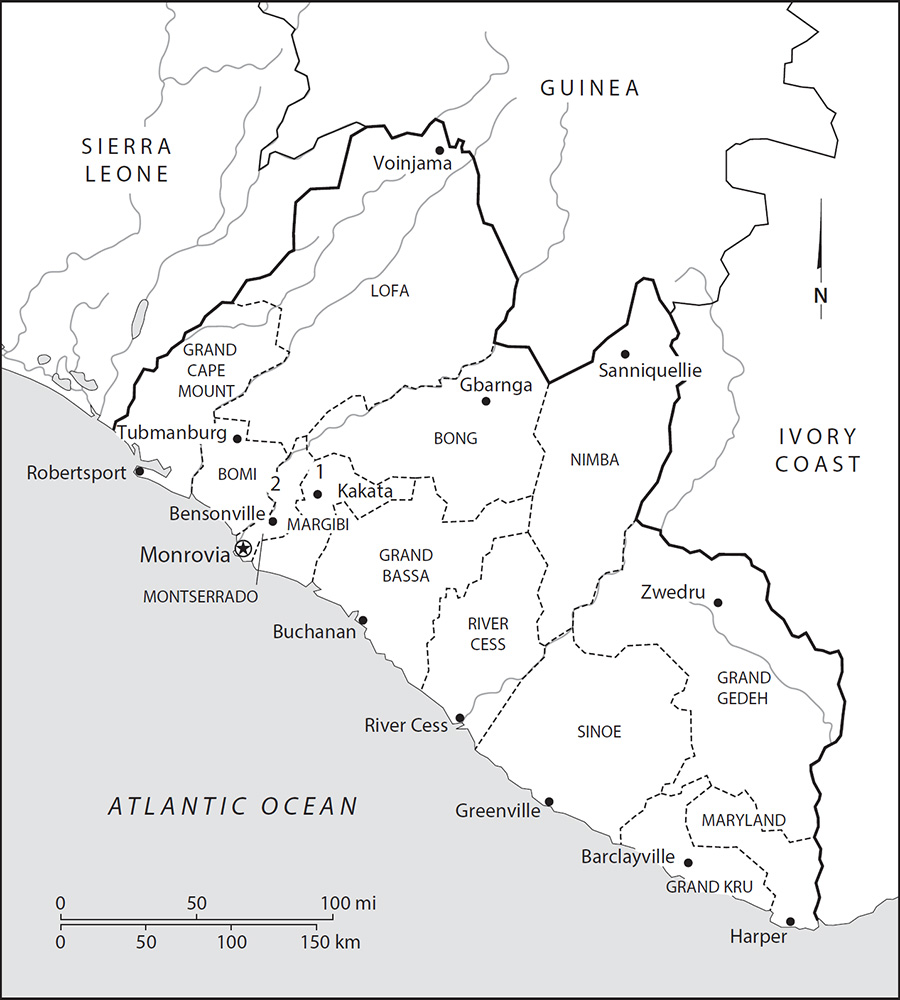

Still, the United States now had its African foothold (Map 6). Indeed, individual states would go on to found colonization societies and their own colonies in West Africa.5 Gradually, the population of these colonies increased and the question of governance had to be addressed. As the US government would not officially take responsibility, it was left to the ACS to appoint agents and in 1838 their status was raised to governor. Their choice in that year was Thomas Buchanan, cousin of a future American president (James Buchanan, 1857–61).

Map 6. Liberia

The patrician Buchanan arrived at Monrovia,6 the capital of the Commonwealth of Liberia (as it had become known), armed with a new constitution drafted by the ACS. Liberia now looked to all intents and purposes like a US colony and set about funding itself through customs duties on imports. These, however, fell on goods exported by other imperial countries (not just the United States).

The countries most affected were Great Britain and France, whose colonies shared (undefined) borders with Liberia. As the principal trading country, the United Kingdom wanted to know what was the legal basis on which Liberia applied taxes on British goods, and the British minister in Washington, DC, wrote in 1843 to Secretary of State Abel P. Upshur for clarification. Upshur confirmed that Liberia was not a formal US colony, but that the US government “would be very unwilling to see [Liberia] despoiled of its territory rightfully acquired, or improperly restrained in the exercise of its necessary rights and powers as an independent settlement.”7

The British government was unconvinced by this argument and encouraged its traders not to pay customs duties. Without such taxes, Liberia was not viable and Joseph Jenkins Roberts, who had replaced Thomas Buchanan as governor in 1841, decided that the only option was to cut the link with the ACS and become an independent republic.

Liberia declared its independence on July 26, 1847. The declaration began with a list of complaints against the United States: “In some parts of that country, we were debarred by law from all rights and privileges of men—in other parts, public sentiment, more powerful than law, frowned us down. We were excluded from all participation in government. We were taxed without our consent. We were compelled to contribute to the resources of a country, which gave us no protection.”8

Despite this, the Libero Americans—a tiny band of less than fifteen thousand—chose a flag modeled on the Stars and Stripes, adopted a constitution drafted by a white jurist from Massachusetts, and included clauses that reproduced the same injustices in Liberia that they objected to in their former home. The most offensive of these were Article 1, Section 11, and Article 5, Sections 12 and 13, effectively excluding the indigenous population from participation in civic life and restricting citizenship and property ownership to the Libero Americans themselves.9

Great Britain was the first to recognize Liberia’s independence and now accepted the right of the government to impose customs duties. However, it was a Pyrrhic victory since Great Britain and France proceeded to challenge the new state’s borders and force territorial concessions. This should have been the moment for the United States to rattle its imperial saber, but the federal government failed to recognize the independence of Liberia until 1862.10

The treaty of recognition gave the United States the right to intervene in Liberia’s internal affairs under certain circumstances.11 The federal government therefore gave support to Liberia in its efforts both to resist territorial encroachments by France and Great Britain and to suppress internal revolts by the indigenous population. These undertakings put a huge strain on Liberia’s public revenue, and in 1871 the government contracted a debt with British creditors for £100,000 (nearly $500,000).

This loan was a textbook example of British imperialism at its most rapacious. After commissions and advance payment of all interest due over the next twenty years, it is estimated that the Liberian government received only £30,000. Fiscal weakness, with the threat of British intervention to ensure debt payments, continued unabated. Finally, in 1908 the Liberian government appealed to the US government for a guarantee of territorial and political integrity.

An earlier appeal might have fallen on stony ground, but this was soon to be the era of dollar diplomacy. President Theodore Roosevelt accepted that “the relations of the United States to Liberia are such as to make it an imperative duty for us to do all in our power to help the little republic which is struggling under such adverse conditions.”12 A commission was then appointed by the secretary of state and dispatched to Liberia.

By the time the commission reported, President Roosevelt had been replaced by President William Howard Taft (1909–13). Taft fully supported the commission’s recommendations, however, of which the most important was for the establishment of a US customs receivership. The Liberian government accepted this, a loan was provided by a US syndicate to pay off the European creditors, and it was agreed that the US customs receiver would also be financial adviser to the Liberian government.

Liberia was now formally a US protectorate, and the financial adviser, in one of his first acts, recommended reimposition of the unpopular hut tax (see note 9). This increased the opposition Libero Americans faced from the indigenous population and led to a series of revolts. Coupled with the loss of customs duties following the outbreak of the First World War, the Liberian government could not service its debt and the US customs receiver accepted the need for default.

Liberia remained a protectorate because of its financial difficulties, but—as had happened in parts of Central America—it would now also come under the sway of a single US company (Firestone). The circumstances under which this happened are worth repeating for the light it sheds on imperialism more generally.

The British government, although victorious, came out of the First World War severely weakened in financial terms. It therefore looked to means by which it could raise money to service its debts to its creditors (principally the United States). Since American imports of rubber were rising rapidly in response to the growth of the motor vehicle industry and UK colonies in Asia controlled a large part of the world’s exports, the British government adopted the Stevenson Plan. This restricted export supply and helped to push up rubber prices.

BOX 3.1

HENRY SHELTON SANFORD (1823–91)

The US government did not initiate the Berlin Conference (1884–85) and did not participate in the subsequent “scramble for Africa.” Yet it did send a high-powered delegation to Berlin that not only endorsed King Leopold II’s scheme for a Congo Free State but also established the ground rules for future colonization of Africa.

The key member of the US delegation was Henry Sanford. Best known for his Florida ventures (the town of Sanford in Seminole County is named after him), he served as a US diplomat in Belgium in the 1860s, where he first met King Leopold II. This friendship led him to support Leopold’s sinister plan in 1876 to establish an International African Association that appeared at first to have philanthropic purposes.

Sanford was drawn to this scheme partly by naïveté (he was dazzled by aristocratic Europe), partly by commercial interest (his business ventures kept failing and he was always looking to rebuild his fortune), and partly by his southern connections (he hoped that the Congo would rival Liberia as “the ground to draw the gathering electricity from the black cloud spreading over the Southern states which . . . [is] growing big with destructive elements”).

Sanford’s greatest success was persuading the US government to recognize the association before the Berlin Conference began. In this he was helped by Senator John Morgan of Alabama, chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee, and a firm believer in African colonization schemes for African Americans. Without this recognition, it is by no means certain that the powers at Berlin would have accepted Leopold’s plans to turn the association into the Congo Free State.

Sanford persuaded the king to allow him to establish the Sanford Exploring Expedition as the first trading company on the Upper Congo. Leopold II’s officials, however, did not give the company the promised support and, like Sanford’s other business ventures, it soon failed. Sanford lived just long enough to realize that he had been duped by Leopold II, whose real interest in the Congo was venal in the extreme.

The big loser from this price increase was the United States, which accounted for about 70 percent of world rubber imports. Three American capitalists—Thomas Edison, Henry Ford, and Harvey Firestone—now swung into action. Edison concentrated on increasing rubber production in the United States, but died before his plans could come into full effect. Ford developed rubber plantations in Brazil (Box 6.1), but these were crippled by disease and labor shortages. That left only Firestone, whose focus was Liberia.

Following intense discussion with US officials, Firestone reached an agreement with the Liberian government in 1926 to lease up to one million acres for ninety-nine years at six cents an acre.13 It also acquired rights “to construct, maintain, and operate roads and highways, waterways, railroads, telephone and power lines, hydroelectric plants, and a radio station powerful enough for direct communications with the United States.” A subsidiary of the Firestone Company then lent the Liberian government $5 million, the servicing of which was guaranteed by various government revenues. For its part, the Liberian government agreed to several actions:

[It] would appoint and pay the salary of: (a) a Financial Adviser, designated by the President of the United States and approved by the President of Liberia; (b) five other officials to organise the customs and the internal revenue administration of Liberia, approved by the United States Department of State; and (c) four American army officers to lead the Liberian Frontier Force, to be recommended by the President of the United States. The Liberian [government] would install the pre-audit system, which gave the auditor the right to monitor Government expenditures [and] would prepare the Government budget in consultation with the American Financial Adviser.14

Liberia was now an extreme version of a US protectorate in which a single company (Firestone) exercised enormous influence alongside the Customs Receiver. Yet Liberia had all the trappings of an independent country, including membership of the new League of Nations. The US Senate, however, refused to ratify the founding treaty, leaving the United States outside the organization. When the League of Nations therefore chose in 1930 to investigate well-founded accusations of forced labor and slavery against the Liberian government, the US government struggled to prevent Liberia becoming a protectorate of the League as well.

US interests were too strongly entrenched in Liberia and the League failed to impose its authority. When the customs receivership and the American protectorate ended, Liberia did not cease to be a part of the US empire. Instead, it allowed the United States to establish military bases in the country at the start of the Second World War and adopted the US dollar as its currency in 1943. With the election to the presidency the following year of William Tubman, Liberia would complete its transition from US protectorate to client state.15

Before the War of Independence, there was no direct British trade with Japan and only a limited one with China. Since Great Britain also prevented its colonies from trading directly with China, no ships from the thirteen colonies had ever gone there. Instead, imports from China (mainly tea) reached the thirteen colonies via Great Britain itself.

Independence therefore brought the prospect of direct trade ties with China, and there was much anticipation of huge profits. China’s population of nearly four hundred million was one hundred times larger than the United States, and it was easy to be carried away by the potential for exports. The first ship, Empress of China, sailed from New York in 1784. As was customary in those days, it sailed eastward around the Cape of Good Hope and returned the following year by the same route.

The owners made a profit, but it was not enormous. Instead, they discovered what the British already knew: China had little need for imports and was not much interested in foreign trade. Thus, an intensive search began for products that might be of value to China. These included the skins of seals and sea otters that could keep the Chinese elite warm in winter, ginseng that was alleged to cure sexual impotency, sandalwood for burning in temples, and even sea cucumbers that were a gourmet’s delight.

As a result of these endeavors, US traders learned a great deal about the Pacific—both its eastern and western coastlines as well as its network of small islands. Soon American merchant ships could be found in the Dutch East Indies, the Philippines (despite Spanish restrictions on trade), Malaya, and Siam (modern Thailand). Indeed, Edmund Roberts (a New England merchant) signed trade treaties with Siam and Muscat in 1835 on behalf of the US government. Three years later Lieutenant Charles Wilkes was dispatched on an epic four-year journey that produced charts of most of the Pacific for the US government and traders.

However, even Yankee ingenuity could not disguise the fact that the value of commodity exports was never enough to cover the cost of imports of tea, silk, and cotton textiles from China. This meant that the balance had to be paid through the shipment of scarce silver coins, and this drained specie from the US economy, creating the risk of deflation.16

US traders therefore adopted the practice that the British East India Company had been engaged in for some time: selling opium to the Chinese. The East India Company had a monopoly on Indian supplies of opium (until 1831), so the US traders had to buy it elsewhere (their favorite source was Smyrna, on the Black Sea). Regardless of the source, however, the Chinese were determined to suppress the trade in opium because of the social problems it caused. The trade was therefore largely illegal even through Canton (the only port permitted by the Chinese emperor to engage in foreign trade).

When China in 1839 cracked down even harder on the illegal opium trade in an effort finally to stamp it out, the British and American traders involved were furious. The US Navy, small and chiefly confined to the Atlantic, was in no position to respond. The British Navy, however, was only too happy to do so and launched what became known as the First Opium War (1839–42). Thus began what the Chinese today call the century of humiliation.

It is fair to say that many ordinary Americans were appalled by this display of British imperialism. That was not, however, the majority view among elites for whom opening China to trade had become an article of faith. Congressman John Quincy Adams, for example, was delighted: “The justice of the cause between the two parties—which has the righteous cause? I answer, Britain has the righteous cause. The opium question is not the cause of war, but the arrogant and insupportable pretensions of China, that she will hold commercial intercourse with the rest of mankind, not upon terms of equal reciprocity, but upon the insulting and degrading forms of the relation between lord and vassal.”17

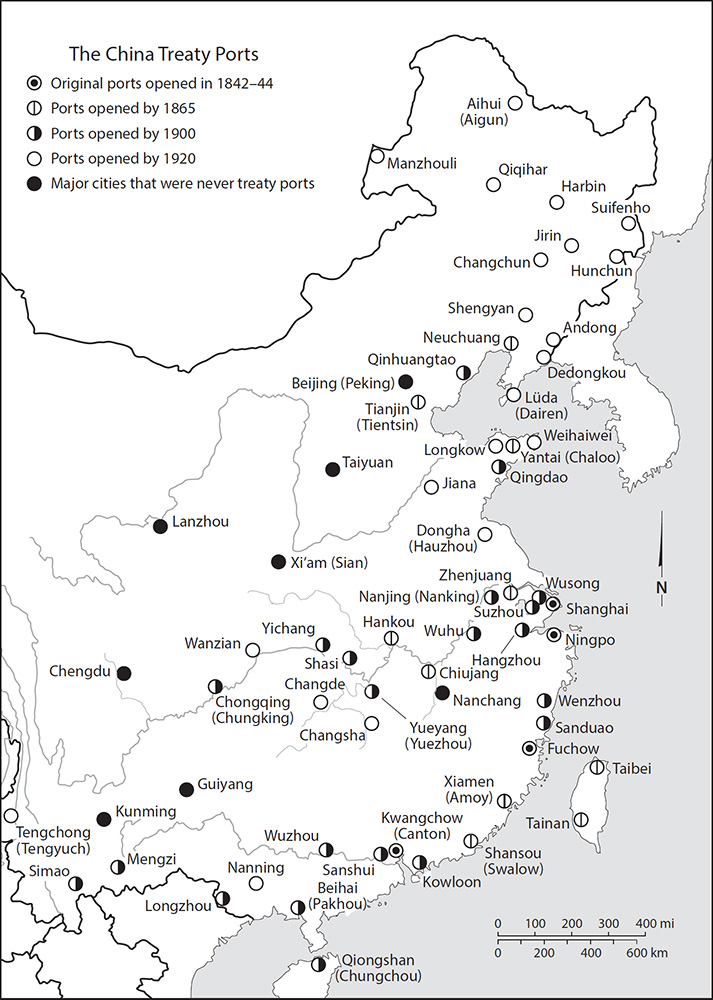

The British emerged victorious, and the Treaty of Nanjing in 1842 gave them what they wanted: a resumption of opium sales, the island of Hong Kong, and greater freedoms for British merchants in Canton. However, the treaty also opened five other ports to British traders and this sent alarm bells ringing in Washington, DC (Map 7). To counter the threat of Great Britain acquiring trading advantages over the United States, President John Tyler quickly sent Caleb Cushing to negotiate a treaty on similar terms to those now enjoyed by the British.

The result was the 1844 Treaty of Wanghia. It was a triumph of US diplomacy, but also the moment that America became an imperialist power in Asia instead of just another trading nation. The treaty not only gave the United States the same rights of privileged access as the United Kingdom to the five ports (Kwangchow, Amoy, Fuchow, Ningpo, and Shanghai) but also for the first time enshrined the concept of extraterritoriality. From now on, US citizens found guilty of crimes against Chinese citizens would not be charged under Chinese law and instead would only have to answer to the US consul in the port concerned. The Chinese government also gave Americans the right to build hospitals, churches, and cemeteries in the open ports.

China included a most favored nation clause in the treaty, meaning that the United States could claim any future concessions granted subsequently to other treaty powers. And, to demonstrate the unequal nature of the treaty, China in Article 2 agreed not to change customs duties without the consent of the United States: “Citizens of the United States resorting to China for the purposes of commerce will pay the duties of import and export prescribed in the Tariff, which is fixed by and made a part of this Treaty. . . . If the Chinese Government desire to modify, in any respect, the said Tariff, such modifications shall be made only in consultation with consuls or other functionaries thereto duly authorized in behalf of the United States, and with consent thereof.”18

The Treaty of Wanghia meant that the Chinese government had partially relinquished its sovereignty, and the implications were soon apparent. In Shanghai, the most important of the five new ports, the United Kingdom and the United States established a system of municipal government, which eventually became known as the Shanghai International Settlement. Its mayor, on one occasion a US citizen, wielded enormous power over a city with more than one million inhabitants. It would survive for almost a century until the middle of the Second World War.

Following the annexation of California and the growing possibility of an interoceanic canal, the federal government became convinced that the Pacific could become a zone of special US influence. However, many obstacles still had to be overcome. Other imperialist powers—notably Great Britain, France, and Russia—had similar ambitions, and they would be joined by Germany toward the end of the century and Japan soon after. Furthermore, the Monroe Doctrine, designed for the Americas, could not be extended to the Pacific with any credibility. Thus, acquiring large swaths of territory in the Pacific was always going to be difficult for the United States.

A small step was taken in the decade after the Treaty of Wanghia when Congress passed the Guano Islands Act in 1856. This controversial piece of legislation gave private citizens the right to claim as US territory any island with guano that was unoccupied and not claimed by other states.19 Within a few years, the United States—helped by the magnificent charts compiled by Lieutenant Wilkes—had accumulated claims to more than sixty islands in the Pacific.20

The status of these islands was at first unclear under federal law, but gradually the idea developed of making some of them “unincorporated territories” (a phrase that would only be formally adopted later). This meant that they had no right to join the Union, but it did mean that no other imperial power could occupy them. Most of the guano islands lost utility once the bird droppings had been removed, but some became permanent US territories. The best known is Midway Island, first claimed in 1859.21

Map 7. China treaty ports

US trade in the Pacific region expanded steadily, if not spectacularly, and most of it was accounted for by China. As sail gave way to steam, it became increasingly important to establish coaling stations where the ships could refuel. Rumors began to circulate of vast coal deposits in Japan, where trade was restricted to the Dutch and Chinese at one port.

Early efforts by the British and the Americans to open Japan to foreign commerce had been unsuccessful, but the rumors of large coal deposits persuaded the United States to try again. Commodore Matthew Perry was the chosen instrument. Although urged not to use force against Japan except in self-defense, Perry was under no illusions about what he was attempting to do. He had considered the opening of the Chinese ports by war as “one of the most humane and useful acts”22 which Great Britain had ever undertaken and he had every intention of doing the same to Japan.

Perry departed for Japan in 1853. On the way he staked a claim to Okinawa in the Ryukyu Islands and purchased one of the Bonin Islands for the United States.23 After a show of force in Edo (Tokyo) Harbor, he left a letter for the Japanese emperor and returned the following year to learn that the Japanese government was willing to grant limited access to US traders at two minor ports. The British—whose foreign secretary had said of Perry’s mission, “better to leave it to the Government of the United States to make that experiment; and if the experiment is successful, Her Majesty’s Government can take advantage of its success”—were quick to follow suit.

Perry is usually credited with opening Japan to foreign trade. However, the real breakthrough came three years later when Townshend Harris negotiated the Shimoda Convention. Japan agreed to open additional ports and conceded extraterritoriality to the United States. This paved the way for a series of treaties, each more unequal than the last, which deprived Japan of the power to set customs duties, opened more ports, and granted religious freedom to foreigners.

These unequal treaties led inevitably to friction, and a series of incidents in 1863 resulted in war between Japan and the imperial powers. The United States was in the middle of its Civil War, so the British navy took the lead. However, it was keen to participate and—despite having only one sailing ship in the area of conflict—was able to join in “when the Americans rented a small, unarmed steamer and transferred a gun and crew from the sailing ship to carry the United States flag into battle.”24

Japan would draw the inevitable conclusions from this and other humiliations at the hands of the imperialist powers: the need to modernize and establish a strong navy. With the restoration of the executive powers of the emperor in 1868, change came rapidly. Japan would now be transformed, and the first real test of its military prowess came in 1894–95 when it defeated China in a dispute over Korea.

So absolute was Japan’s victory (due mainly to sea power) that the treaty powers had to intercede to prevent Japan from carving out too many concessions from China for itself. In return, Japan was able to renegotiate the unequal treaties signed with the treaty powers. It entered the twentieth century with its sovereignty fully restored and was now on course to becoming an imperialist country itself.25

In China, meanwhile, the humiliations at the hands of foreigners continued, with the United States prominent among the treaty powers responsible. The long-running Taiping Rebellion (1850–64) could only be suppressed with the help of foreign forces, which led to further concessions to the United States and other imperial countries through treaties. The Chinese government, for example, lost the right to set its own tariffs, and the United States won the right to establish a court in its Shanghai consulate to try any of its citizens accused of a crime.

Although the United States did not take part in the Second Opium War (1856–60) and the destruction of the Summer Palace, it took a leading role in bombarding Formosa (Taiwan) a few years later in response to acts of piracy. It also passed the China Exclusion Act in 1882, restricting Chinese immigration to the United States. And in 1888 it passed a further piece of legislation, which caused even deeper offense in China, making it impossible for any Chinese in the United States to return after visiting China.

Most serious of all was the response of the treaty powers to the Boxer Rebellion (1898–1900).26 The China Relief Expedition, comprising eight nations including the United States, invaded China in 1900 and penetrated as far as Beijing to protect their nationals and put down the uprising.27 Looting and other outrages by all foreign troops were commonplace, while the Chinese government was forced by the Boxer Protocol in 1901 to pay an enormous indemnity to their governments. Cartoons captured the mood.28

Such was China’s weakness that it now risked being dismembered by the imperialist countries. Yet this was a danger for the imperialists as well. Not only would it increase the chance of an interimperial war, but it would also lead to the disintegration of the fabled Chinese market. Although it had often disappointed, Chinese imports could still be enormous provided that its territory was preserved.

It was at this point that US Secretary of State John Hay published his two “Open Door” notes and none of the other treaty powers objected.29 China would not be carved up, there would be equal access (at least for the treaty powers), and there would be no war. However, China was still subject to unequal treaties, and even more restrictions were placed on the Chinese in America (Chinese merchants responded with a half-hearted boycott of US goods). President Taft also deployed dollar diplomacy to put together an international consortium to keep China open for investment and stabilize its currency.

The United States was by no means the worst offender among the imperial powers in China. However, that misses the point. It was one of the powers that heaped humiliation on China and restricted its sovereignty. Thus, for the Chinese there was no reason to distinguish between the United States and other countries unless they saw some opportunity to play one off against the other. And America was content to work with the other imperial powers where necessary in order to secure its interests.

By virtue of its location in the middle of the Pacific (see Map 8), Hawaii was always going to excite the interest of imperialists. Great Britain was the first, based on the voyage of Captain James Cook in 1778 and the “cession” of the islands to Captain George Vancouver in 1794, but the claim was never seriously pursued. France and Russia would also claim Hawaii based on even more tenuous justifications.

The country that established the most powerful presence in Hawaii was in fact the United States. First to come were the traders loaded with skins and furs from the Pacific Northwest, using Hawaii as a base on their way to Canton in China and purchasing sandalwood. Then the whaling ships arrived, using Hawaii not only as a place to obtain provisions but also to rest between seasons.

Even more significant was the arrival of American missionaries in 1820. In an effort to resolve doctrinal disputes in New England, an American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) had been set up in 1810. US missionaries had then fanned out across the Pacific, reaching Burma, British India, and China. The reception was not welcoming, and the missionaries sent to Hawaii probably expected something similar.

Fortunately for the missionaries, King Kamehameha I had died the year before they arrived. His successor, Liholiho (Kamehameha II), was a modernizer who was prepared to break many of the old traditions. He allowed the missionaries to settle among his 100,000 subjects, and soon they had established schools, a printing press, and a written language.

When Liholiho died in 1824 during a state visit to Great Britain, he was succeeded by Kauikeaouli, his son of twelve years. Although King Kamehameha III (as he was now called) had regents, the missionaries soon acquired a position of importance as advisers and mentors. Indeed, the first treaty between the United States and Hawaii was signed in 1826, although it was never ratified by Congress.

Kauikeaouli attended a Christian school and learned to read and write. However, what he desired above all was recognition of Hawaii by the imperial powers in order to put its independence on a more secure footing. He therefore sent a two-person delegation to Washington, DC, in 1842. One was Timoteo Haalilio, a Hawaiian noble, while the other was William Richards, a former American missionary.30

The negotiators met Secretary of State Daniel Webster and President Tyler. Both procrastinated over recognition until the Hawaiian delegation hinted at the possibility of becoming a protectorate of another power. This did the trick, and Tyler gave the following endorsement:

Considering, therefore, that the United States possesses so very large a share of the intercourse with those islands, it is deemed not unfit to make the declaration that their Government seeks nevertheless no peculiar advantages, no exclusive control over the Hawaiian Government, but is content with its independent existence, and anxiously wishes for its security and prosperity. . . . Its forbearance in this respect, under the circumstances of the very large intercourse of their citizens with the islands, would justify the Government, should events hereafter arise, to require it, in making a decided remonstrance against the adoption of an opposite policy by any other power.31

The Tyler Doctrine, as it would become known, was therefore much more than recognition of Hawaiian independence. It effectively turned Hawaii into a US protectorate, since its government was no longer free to conduct relations with other foreign powers without taking into consideration US interests and could not now contemplate becoming a dependency of any European country.

Map 8. American possessions in the Pacific

Hawaii was now inside the US sphere of influence, but commercial developments would take it even further. Sugar had first been exported in 1839, and the industry grew modestly until two things happened. First, the United States acquired Oregon and California at the end of the 1840s, giving Hawaii a new market for sugar. Second, the whaling industry went into decline at the end of the 1850s, leading to a search for alternative exports.

Sugar development brought US capital to Hawaii in vast quantities. It forced an end to feudalism and allowed for foreign ownership of land. It also created a demand for labor that could not be met locally, leading to mass immigration of Chinese and Japanese workers. However, Hawaiian sugar had to compete in the US market with other foreign sugars as well as domestic cane and (later) beet sugar. This led to calls either for annexation or for “reciprocity,” under which Hawaii would have duty-free access to the US market in return for zero tariffs on US imports.

Negotiations nearly reached a successful conclusion in the 1850s, but were then interrupted by the Civil War. When talks on reciprocity restarted, they were complicated by the death of King Kamehameha V in 1872. His successor died in February 1874 and US troops landed to put down a rebellion against the new king (David Kalakaua). From then onward negotiations proceeded rapidly, and the Reciprocity Treaty was concluded in 1875.

Such treaties were and are commonplace and need not be imperialist in character. This was no ordinary treaty, however, as Article 4 made clear: “It is agreed on the part of His Hawaiian Majesty, that, so long as this treaty shall remain in force, he will not lease or otherwise dispose of or create any lien upon any port, harbor, or other territory in his dominion, or grant any special privilege or rights of use therein, to any other power, state, or government, nor make any treaty by which any other nation shall obtain the same privileges, relative to the admission of any articles free of duty, hereby secured to the United States.”32 Article 4 not only further restricted the sovereignty of the Hawaiian government but was also included as a result of the refusal of the Hawaiian negotiators to lease Pearl Harbor to the United States under the treaty. By 1887, however, Hawaiian resistance had ended and Pearl Harbor came into US possession as part of the renegotiation of the 1875 Treaty of Reciprocity.

Reciprocity and Pearl Harbor were more than sufficient to secure US interests, but Hawaii was still nominally sovereign. This did not matter as long as the monarch was pliant, but in 1891 Queen Liliuokalani (Box 3.2) ascended the throne. She had been born in 1838 and she had seen the sovereignty and independence of the kingdom steadily compromised. The native population was in decline and was now in a minority, while US settlers and their descendants dominated commerce and politics. To make matters worse, the McKinley Tariff in 1890 had wiped out the advantages of the Reciprocity Treaty.33 It was time, she decided, to take a stand.

The queen miscalculated, and those in favor of annexation gained the upper hand. Domestic considerations in the United States delayed passage of an annexation treaty until 1898 and Hawaii then became a US territory in 1900. Its transition to statehood was held up first by southern resistance to a nonwhite population and then by the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941. It would eventually join the Union as the fiftieth state in 1959.

While Hawaii gave the United States a foothold in the northern Pacific, eastern Samoa would do the same in the southern part of the ocean. The Samoan Islands occupy a strategic position between the Americas and Oceania and are directly on the trading routes from Hawaii to Australia. The neighboring islands—Fiji, Tahiti, Tonga, and the Cooks—had excited the interest of European imperial powers since the late eighteenth century, and it was therefore to be expected that the United States would seek to establish a presence in the region.

BOX 3.2

QUEEN LILIUOKALANI (1838–1917)

Liliuokalani was the daughter of a close adviser of King Kamehameha III. She attended a missionary school and married John Owen Dominis, the son of a US sea captain. She was groomed for many years to ascend to the throne and traveled to London in 1887 for the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria. It was the same year that King Kalakaua was forced by US interests on the island to accept the so-called Bayonet Constitution that weakened the powers of the monarchy.

On ascending to the throne in 1891, Queen Liliuokalani was determined to adopt a new constitution that would have restored the monarch’s powers. Unable to do so through parliament, she attempted to do so by decree. She was then overthrown in January 1893 by annexationists led by Sanford Dole, who was backed up by US troops on board the USS Boston. A treaty of annexation was then hastily prepared by President Benjamin Harrison (1889–93), but he left office before it could be adopted by Congress.

His successor, President Grover Cleveland (1893–97), dispatched James Blount to investigate the circumstances surrounding the coup, and Blount’s report condemned US interference. Before the queen could be restored to power, however, the Senate commissioned its own report chaired by John T. Morgan. This document, dismissed by the Philadelphia Record as “a mere incoherent yawp of jingoism,” was enough to preserve the status quo.

Cleveland, despite his reputation as an anti-imperialist, then recognized Sanford Dole as president of the Republic of Hawaii. Dole imprisoned Liliuokalani in 1895 and she was not released until November 1896. She immediately traveled to Washington, DC, but her cause was now hopeless. She returned to Hawaii, where she lived until her death in 1917. She continued to write songs, her best known one being “Aloha Oe,” and remained an accomplished musician (she played the piano, ukulele, guitar, zither, and organ).

US troops landed in Samoa as early as 1841 to burn villages in retaliation for the murder of a US sailor by natives. However, the British already had a strong position on the islands and it was not until 1873 that a coherent US imperial plan took shape. In that year Albert Steinberger was dispatched by President Ulysses S. Grant to Samoa as a special envoy to explore the possibility of securing a US protectorate.

At the time Samoa was recovering from a civil war between the two leading families (Malietoa and Tupua). Steinberger was therefore invited to draft a constitution which was adopted with himself as premier. This gave him supreme executive power and should have marked the moment all Samoa became a US colony. However, Steinberger’s actions earned the enmity not only of Great Britain and Germany but also the US consul.

Steinberger was deposed in 1875 before American control could be consolidated, but three years later the Samoan government agreed to a treaty in Washington, DC, that gave the US government what it really wanted: a coaling and naval station at Pago Pago Harbor on Tutuila Island in eastern Samoa. However, the treaty also committed the United States to mediate between Samoa and other powers.

Disputes escalated rapidly and centered on many issues, including land ownership. Samoan tradition required that land be held communally and—unlike in Hawaii—the law had not been changed. This meant that bribery and corruption by foreigners were common in an effort to gain de facto control of land, and one of the principal offenders was the US Central Polynesian Land and Commercial Company (CPLCC).34

An effort was made in 1887 by the three principal powers—Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States—to resolve their differences, but to no avail. Two years later it would have come to war in Samoan waters if it were not for the eruption of a powerful storm. Chancellor Bismarck then summoned the powers to Berlin, where a joint protectorate was established over the islands by Germany (in the west), Great Britain (undefined), and the United States (in the east). This left America in control of the harbor at Pago Pago, its most important strategic objective.

The Samoan government was still nominally sovereign and so the opportunities for misunderstanding and meddling by the foreign powers were legion. In 1899, therefore, the three powers agreed to a formal division of labor. Western Samoa became a German colony (it would be given to New Zealand by the League of Nations after the First World War) and the rest became the US colony of American Samoa. Great Britain dropped its territorial claims.

The act of annexation was signed by President William McKinley (1897–1901), who—in recognition of the importance of the harbor at Pago Pago—promptly passed American Samoa to the US Navy. Congress played no role in this imperial episode until 1929, when the cession to the United States was formally approved.35 American Samoa would remain a responsibility of the US Navy until 1951, when civilian rule under the Department of the Interior was established. American Samoa remains a US colony today.

Alaska, the Russian colony in the Pacific Northwest, had been administered by the Russian American Company (RAC) since its foundation in 1799, with the state as a minority shareholder. The company at first was highly profitable, but the decline in the number of skins and furs as a result of overfishing by American, British, and Russian sailors soon changed this. The Russian government did not wish to subsidize the RAC and, following a gloomy report on the company’s prospects in 1862, resolved to sell the territory.

Russia could conceivably have offered Alaska to Great Britain, but relations were much better with the United States. Since the borders of Alaska (including the Aleutian Islands and other islands) had been largely defined in the Anglo-Russian Convention of 1825, negotiations were straightforward. A price of $7.2 million was agreed to in 1867, and the sale was approved by the US Senate after a mammoth three-hour speech in support by Senator Charles Sumner.

Neither Senator Sumner nor the United States and Russian governments paid the slightest attention to the indigenous population, whose numbers were estimated at 26,000 (or 27,500 if the mixed population is included). Since the white population was only 483, of which 150 were Americans, the US government decided that Alaska could not become a territory. The new colony was therefore placed under military rule.

Military rule was not uncommon in building the US empire, but it lasted for longer in Alaska than anywhere else. The absence of any representative institutions meant that the more unscrupulous elements of US society were able to operate without much accountability. In particular, Alaska came to the attention of the Guggenheim company, which established an Alaskan syndicate to create a series of monopolies in natural resource extraction, transport, and power.

The population grew slowly until the discovery of gold in the Klondike River in 1896. This produced the inevitable gold rush and a jump in the number of white settlers from around six thousand in 1890 to thirty-four thousand in 1900. This was more than enough for Alaska to proceed to the first stage of territorial government, but there were still further delays. Indeed, it was not until 1912 that Alaska became a US territory.

Territorial government in Alaska was even more “colonial” than in other US territories. The act establishing a territory limited the powers of the legislature: “It may not pass any law interfering with the primary disposal of the soil; it may not levy taxes that are not uniform upon the same class of subjects; it may not grant any exclusive or special privileges without the affirmative approval of Congress . . . it may not authorize . . . any debt by the Territory . . . it may not appropriate any public money for the benefit of any sectarian or denominational school . . . it may not alter, amend, modify or repeal the game and fish laws passed by Congress and in force in Alaska.”36 The last point was particularly resented by the population—settler and indigenous—as it suggested that Alaska had become an early experiment in conservation by Congress.37 The native population, however, had no way of protesting until 1915 when they were granted citizenship—albeit under highly restrictive conditions.

By the end of the Second World War, the population was large enough for statehood to be considered. A referendum was therefore held in 1946, with a majority in favor. However, more than 40 percent voted against, so it was some years before the territory could join the Union.38 This finally happened in January 1959, bringing to an end nearly a century of US colonial rule in Alaska.

The Philippines were added to the Spanish empire in 1565. For the next three centuries Spanish authority went largely uncontested not only in the archipelago but also in the surrounding islands of Micronesia. These included the Mariana, Carolina, and Marshall Islands, which Spain claimed but—with the exception of Guam—had not occupied or fortified in any meaningful way. Nor had Spain resisted the arrival in the second half of the nineteenth century of Protestant missionaries and foreign traders as permanent residents.

Inevitably, these small island groups began to attract the attention of the other imperial powers. Of these, Germany was the most assertive and in 1885 she occupied a number of islands in both the Carolinas and the Marshalls. Spain protested and war was only avoided when both sides agreed to a German proposal to seek arbitration by Pope Leo XIII.

The Protocol of Rome, drawn up by the pope at the end of 1885, acknowledged Spanish sovereignty over the Carolinas. However, it was a Pyrrhic victory. Germany was left in control of the Marshall Islands with the right to establish coaling and naval stations in the Carolinas. Furthermore, Spain’s subsequent attempts to conquer the Carolina Islands provoked considerable resistance from the indigenous population and demonstrated to other powers how militarily frail she was.39

These events did not go unnoticed in the United States, whose missionaries had long been established in many of the islands. Spanish weakness also drew US attention to the Philippines, where resistance to imperial rule had been building up since the 1860s. The archipelago, so close to the Chinese mainland, occupied a strategic position and made its control a tempting proposition for any power interested in increasing trade with Asia.

The Filipinos, as the indigenous people were called by foreigners, had no desire to replace Spanish rule with that of another imperial power. By the 1890s they had formed a powerful nationalist movement led by Emilio Aguinaldo with the goal of independence or, at least, autonomy. By April 1898 the rebels were largely in control, and the Spanish forces were pinned down in Manila. Spain was unable to provide adequate reinforcements due to the Second War of Independence in Cuba (1895–98), and the Filipino insurgents looked forward to victory.

It was at this point that the United States declared war on Spain. Although the principal motivation was to end Spanish rule in Cuba and Puerto Rico, President McKinley had, even before the declaration, taken the precaution of moving the US Asiatic Fleet under Commodore Dewey to Hong Kong in preparation for an assault on the Spanish fleet in Manila Bay.40 As soon as war was declared, the Spanish fleet in the harbor was utterly destroyed.41

Dewey, soon to be made an admiral, lacked the land forces to take Manila. The Filipino rebels could have taken it, but this would have left them in control of the Philippines. American reinforcements were therefore quickly dispatched from the mainland, stopping briefly at Guam in the Marianas to annex the island.42 The rebels were told firmly to stay away, and Manila was surrendered by Spain with scarcely a shot being fired.43

Whatever doubts President McKinley may have had about advancing US imperial ambitions had been resolved by the time of the Paris peace conference in December 1898.44 Both Guam and the Philippines were ceded by Spain to the United States, and the indigenous peoples were not consulted. The United States did not, however, take the Northern Marianas or Carolina Islands although she could undoubtedly have done so if she wished.45 As Spain was now in no position to hold them, she sold them in 1899 to Germany.

Guam was put under the control of the US Navy, which proceeded to govern the island with very little oversight from Congress or any other institution.46 The 7,100 islands making up the Philippine archipelago could not be controlled so easily since the forces under Aguinaldo’s command had no intention of laying down their arms. The United States therefore engaged in a ferocious colonial war in which torture was common and the civilian population was herded into concentration camps.47

Aguinaldo was captured in 1901 and the worst of the fighting was over by the following year. The number of Filipino deaths will never be known for certain, but it has been estimated as high as 250,000 when disease and starvation are taken into account.48 US imperialists, however, never doubted the virtue of their cause. In October 1900 the secretary of war, Elihu Root, stated, “Nothing can be more preposterous than the proposition that these men [the Filipino forces under Aguinaldo] were entitled to receive from us sovereignty over the entire country which we were invading. As well the friendly Indians, who have helped us in our Indian wars, might have claimed the sovereignty of the West. They knew that we were incurring no such obligation and they expected no such reward.” 49

BOX 3.3

“THE WHITE MAN’S BURDEN”

Rudyard Kipling (1865–1936) was an Anglo-Indian writer famous for his poems and children’s stories. He was also a staunch defender of British imperialism. Yet his most famous imperialist poem is addressed to the people of the United States and concerns the Philippines.

Kipling’s wife was American, and they honeymooned in the United States. They then set up home in Connecticut, where he wrote many of the works for which he is most famous. Although not living in the United States at the time of the Spanish-American War, he sent a copy of his paean to imperialism, “The White Man’s Burden: The United States and the Philippine Islands,” to Theodore Roosevelt in November 1898 urging him to support colonization.

Roosevelt sent the poem to Senator Henry Cabot Lodge with a note extolling its imperialist message but deploring its literary merit. Lodge, who received it shortly before the Senate voted on annexation of the Philippines, replied that he liked both the message and the poetry. The poem was published in McClure’s magazine in the same month as the Senate vote (February 1899).

The poem has been much admired by imperialists through the ages, and some of its words were used by Max Boot in 2002 in the title of his book (The Savage Wars of Peace) in defense of US empire. It also provoked a series of hostile responses from anti-imperialists and satirists. In April 1899, for example, H. T. Johnson—an African American clergyman—published a poem that included the following lines: “Pile on the Black Man’s Burden / His wail with laughter drown / You’ve sealed the Red Man’s problem, / and will take up the Brown.”

In the same year, Henry Labouchère published in Truth magazine perhaps the best-known riposte to Kipling, with the immortal lines, “Pile on the brown man’s burden, / compel him to be free; / Let all your manifestoes / Reek with philanthropy.”

Guam and the Philippines were now US territories, but their legal status was still ambiguous. Hawaii had been annexed in 1898 and was on the long path to statehood. Eastern Samoa, on the other hand, had become a US colony the following year with no prospect of joining the Union. The same was true of all those possessions, such as Midway Island, acquired by the United States under the Guano Islands Act. What should happen to Guam and the Philippines?

There was little support in the United States for statehood to be given to the new territories. Guam was too small, and the nonwhite population of the Philippines too large (about 10 percent of the US population). The Supreme Court was therefore asked to rule on the status of the new possessions in a series of decisions that became known as the Insular Cases.50

The Supreme Court proved to be a very malleable tool in the service of US imperialism. The judges, albeit by a narrow majority, established that Guam and the Philippines were “unincorporated” territories and therefore not entitled to statehood.51 Indeed, in a ruling that left most people puzzled, the court ruled that the inhabitants of unincorporated territories were only entitled to “fundamental” rights under the US Constitution, but not “formal” or “procedural” rights.52

The path was now cleared for the US administration and Congress to do whatever it wanted. Guam was left under the control of the US Navy and would remain there until 1951, when civilian rule was finally established. An Organic Act for the Philippines was passed in 1902 that gave some concessions to exporters, but still left the country outside the US tariff wall (it would only come inside after 1909).53 And to ensure that a lobby was not formed pushing for statehood, Congress imposed various restrictions on US inward investment into the Philippines.54

Once inside the tariff wall, Philippine exports of sugar, hemp, tobacco, and coconut oil expanded rapidly and began to challenge domestic producers in the United States. Filipino workers, taking advantage of one of their “fundamental” rights under the US Constitution, also started moving to the mainland in significant numbers.55 Opposition to the Philippines’ unincorporated status became more and more vocal both from those demanding restrictions on Philippine exports and from those calling for an end to immigration.

Congress was powerless to act unless the Philippines ceased to be a US colony. The Great Depression, however, finally tipped the balance. Domestic producers were now more determined than ever to block Philippine exports, while mainland unemployment rendered unrestricted Filipino migration even more controversial. With the passage of the Tydings-McDuffie Act in 1934, a schedule was set for eventual independence. Filipino immigration and unrestricted trade ended immediately.56

Plans for independence were interrupted by the outbreak of the Second World War and the Japanese invasion of the Philippines in 1941. When independence finally came in 1946, it was hedged around with so many restrictions that it would be more accurate to describe the Philippines as becoming a US protectorate. Thus, the end of colonialism in the Philippines did not mean the end of US imperial control.

The United States retained its gigantic naval and air bases and would not relinquish them until 1992.57 Under the Bell Trade Act, which the Philippine government signed two days before independence, the United States set out the tariff schedule and export quotas to be applied for the next three decades, pegged the currency to the US dollar, and awarded parity to American individuals and corporations in the exploitation of the country’s natural resources.58 Since this last provision conflicted with the Philippine Constitution, the US legislators took the precaution of adding, “The Government of the Philippines will promptly take such steps as are necessary to secure the amendment of the Constitution of the Philippines so as to permit the taking effect as laws of the Philippines of such part of the provisions of Paragraph 1 of this Article as is in conflict with such Constitution before such an amendment.”59

By the beginning of the twentieth century, the US empire in the Pacific was well established and in geopolitical competition with the empires of France, Great Britain, and Germany. Japan had also become an imperial power, especially after its military victories against China in 1895 and Russia in 1905, but it did not yet control any islands close to US possessions.60

All this would change with the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914. Japan immediately occupied the German islands in the Marianas, Carolinas, and Marshalls with little resistance from either Germany itself or the local population. The methods, however, were frequently brutal. The United States, neutral until April 1917, could do nothing and looked on with some concern.61

When the war ended, Japan looked for diplomatic support to keep the islands it had occupied. It found a willing ally in Great Britain, with whom it had been in alliance since 1902 and who had also seized a number of German territories in the Pacific.62 The United States, however, resisted and President Woodrow Wilson (1913–21) argued at the peace conference in Paris that all the German territories should be governed as League of Nations’ mandates without the administering nation exercising full sovereignty.

The US proposal carried the day, but not before the British had emasculated it by proposing a threefold categorization of mandates. The Japanese-held islands were put in Class C, meaning that Japan could now do what she wanted, and she proceeded to turn them into traditional colonies.63 When Congress rejected the 1920 Treaty of Paris, Wilson tried again in his last months to “internationalize” the Japanese islands. His successor, President Warren G. Harding (1921–25), won a few minor concessions, but not enough to change the fact that Japan had gained colonies close to the American ones.64

The United States now faced a formidable competitor, and the more astute American strategists began to anticipate trouble.65 The bombing of Pearl Harbor in December 1941 proved them right. The war against Japan lasted nearly four years but, when it ended, the United States was left in control of all the Japanese islands in the Pacific and the question immediately arose of what to do with them.

The solution was very much the same as that found for Japan after the First World War.66 The new imperial acquisitions, covering a sea area of three million square miles, were renamed the United Nations Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands (TTPI).67 They included the Carolinas, the Marshalls, and the Northern Marianas.68 All the islands were now US colonies, but their colonial status had become something of an embarrassment by the 1970s. The United States, in consultation with the local peoples, was therefore obliged to come up with new constitutional arrangements.

The answer was found in most cases through “independence” in “free association with the United States.” Three new states were born—Palau, the Federated State of Micronesia,69 and the Marshall Islands—and joined the United Nations, although the United States controls their defense and foreign affairs (the three states invariably vote with the United States).70 The Northern Marianas, however, chose to remain a colony under the name Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands.71

The US territorial empire in the Pacific has therefore not ended, although it is much smaller than when it included the Philippines. Alaska and Hawaii have become states, but Guam, Samoa, Palau, the Marshall Islands, the Federated State of Micronesia, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, Midway Island, Wake Island, Johnson Atoll, Kingman Reef, Palmyra Atoll, Jarvis Island, Baker Island, and Howland Island are all imperial responsibilities. It is quite an impressive list for a country that officially does not have an empire!