Despite geographic proximity, the American empire was slow to reach the Caribbean. This was not for lack of interest. The republic had early on acquired a geopolitical stake in the region as a result first of the Louisiana Purchase (1803) and, second, the acquisition of Florida (1819). The United States now had a Caribbean shoreline and all parties shared a desire both to promote commerce with the new neighbors and to protect America from possible attack by European powers.

Slave-owning Cuba was the largest island in the Caribbean, with by far the most dynamic economy until the 1870s. The interest in annexing Cuba before the US Civil War was therefore immense among the southern states, but—as the jewel in their crown—the Spanish had no desire to sell it. After the Civil War, slave-owning Cuba was no longer a target for US acquisition. It was only after the final emancipation of the slaves in 1886 that control of Cuba once again became a US priority.

If US interest in Cuba initially declined after the Civil War, the opposite was true in the case of the rest of the Caribbean. By 1870 one-third of all US imports came from the Americas, and much of it passed through the Caribbean. This meant there was a pressing need for naval bases and coaling stations to defend the sea lanes. At the same time, US interest in an interoceanic canal was stronger than ever after the Civil War, and this would also require naval bases in the Caribbean whichever route was chosen.

Yet the expansion of the US empire into the rest of the Caribbean faced the same obstacles as with Cuba. Almost all islands were colonies of European powers, so that a transfer of sovereignty was only possible if either a sale could be agreed or a successful military campaign undertaken. However, the United States was not prepared for military action so soon after the Civil War, and an attempt to purchase the Danish West Indies in 1867 failed.

There were, nevertheless, two Caribbean countries that were not ruled by European powers. The first was Haiti, which had thrown off the shackles of France after a successful slave revolt and declared its independence in 1804 (the Haitians had defeated an invading British force as well). The second was Santo Domingo, later renamed the Dominican Republic,1 which had revolted against Haitian rule and become independent in 1844. Both nations had splendid natural harbors that would have provided coaling stations and appropriate bases for the US Navy if terms could be agreed.

The two countries, which share the island of Hispaniola, came under enormous pressure from the US administration to make territorial concessions. Yet the Haitian government, which was only recognized diplomatically by the US government in 1862, refused to budge. For this it would pay a heavy price.

The Dominicans, on the other hand, were very receptive. A treaty of annexation was signed in 1869, and the country would have become a US territory the following year if President Ulysses S. Grant (1869–77) had been able to muster the necessary two-thirds majority in the US Senate. He failed, and his subsequent effort to secure annexation through a joint resolution of both houses of Congress (as happened with Texas) was also unsuccessful.

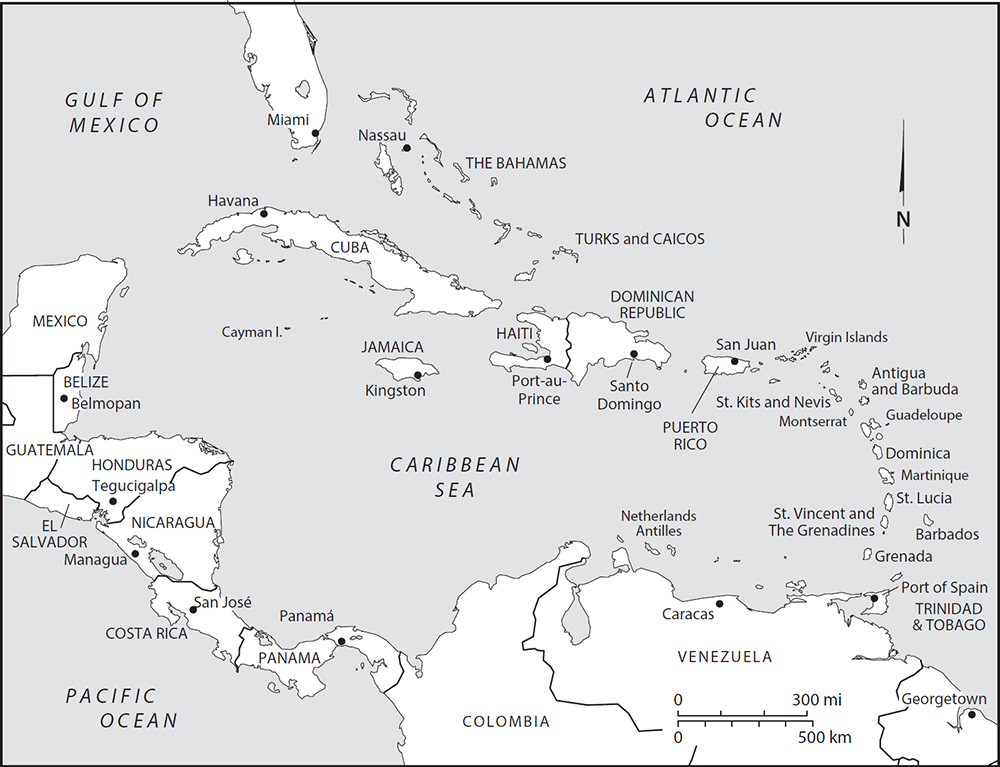

An American empire in the Caribbean could not therefore begin in earnest until after the Spanish-American War (1898) despite the fact that it had been a dream of some of the Founding Fathers more than a century before. Yet in the next five decades, it would eclipse the European powers and turn the Caribbean into an American lake (Map 9). Hundreds of young men and women would work in the region in civilian roles and thousands of troops would be stationed there. There was an enormous attention to detail in social and economic planning.

Two territories (Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands2) became US colonies. Three others—Cuba, the Dominican Republic, and Haiti—were controlled through a series of devices that would have been familiar to European imperialists. These included military occupation, customs receiverships, naval bases, asymmetrical bilateral treaties, and US foreign investment. The widespread use of the US dollar was also an effective form of control (the British, Dutch, and French used the same technique in many of their dependencies beyond the Caribbean where the pound, guilder, and franc circulated freely).

Above all, the US authorities knew that no government in the “independent” countries of the Caribbean could survive for long in the face of nonrecognition. This weapon in the imperial armory was extremely powerful. It meant that aspiring politicians needed to win the support of the United States before taking power (those that failed to do so were very vulnerable). And this tactic was effective not just in the Caribbean but also elsewhere in Latin America.

Map 9. The Caribbean and Central America

Despite such a degree of imperial control, this was not always how it seemed to US officials. Those “on the ground” constantly complained of the difficulties of securing US interests, of disloyalty by favored politicians, of duplicity by governments. This was a constant complaint by imperial officials around the world: the “native” could never be trusted, and no good deed ever went unpunished. The British, Dutch, and French would say much the same.

Once started, the American empire in the Caribbean was constructed swiftly. Opposition to it outside the United States was slower to emerge—except in the countries directly affected. However, imperial possessions sat uneasily with US rhetoric about itself and its place in the world. Indeed, the negotiations at Paris conducted by President Woodrow Wilson in 1919, in which he called for a League of Nations and self-determination for national peoples, were greatly complicated by the US occupations at the time of Haiti, the Dominican Republic, and Nicaragua.

This conflict between rhetoric and reality became worse in the 1920s and reached a climax at the Sixth Pan-American Conference in Havana in 1928. An Argentine diplomat, Honorio Pueyrredón, even had the audacity to introduce an open declaration against US military intervention in which he stated, “Diplomatic or armed intervention, whether permanent or temporary, is an attack against the independence of states and is not justified by the duty of protecting nations, as weak nations are, in their turn, unable to exercise such right.”3

US policy emerged from Havana battered and bruised. It was clear therefore that a new approach to hemispheric affairs was required. This would be announced by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) in his inaugural address in March 1933 where he outlined the Good Neighbor policy. Later that year he confirmed that “the definite policy of the United States from now on is one opposed to armed intervention.” 4

In US mythology this was the moment when the imperial project, initiated after the Spanish-American War, came to an end. Troops were withdrawn from Haiti and Nicaragua and the Platt Amendment5 was revoked, leaving Cuba in theory as a sovereign independent nation. By the end of the 1930s even intervention in Panama had been foresworn. Yet, as we will see, imperial retreat was far from being the case. The empire survived, but the methods to sustain it changed.

American empire always secured what it wanted in the Caribbean on matters of national importance even after the adoption of the Good Neighbor policy (at least until the Cuban Revolution), only losing out on relatively trivial issues. As an exercise in imperialism, the US empire in the Caribbean up to the end of the Second World War and even beyond was as complete as any in history. It even brought about the subordination of the colonies of other empires—something that Belgian, British, Dutch, French, or Italian officials could only dream about as they competed with each other in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East.

If Haiti was off-limits to US colonization in the nineteenth century, the Dominican Republic was a different story. A weak and fragile state on independence, it feared being recolonized by Haiti and sought a foreign protector. All the major European powers were approached and the country even became a Spanish colony for a few years (1861–65), a violation of the Monroe Doctrine made possible by the distractions of the US Civil War. However, Spanish rule proved unpopular and was ended by a successful revolt.

President Grant now seized his opportunity. Not only did the Dominican Republic at Samaná Bay have one of the finest natural harbors in the Caribbean, but its political and economic elites were also keen for the country to join the United States. A treaty was drawn up with President Buenaventura Báez of the Dominican Republic and presented to the US Senate in 1869.

The treaty provided for annexation of the whole country with the promise of eventual Dominican statehood and a payment of $1.5 million (an alternative treaty was also drafted that would have given the United States a lease on Samaná Bay only). The US Navy stood offshore to reinforce the message, and Haiti, which still claimed the eastern half of the island, was warned to expect repercussions if she tried to block annexation.6

This would have been the first US territory in the Caribbean, but the treaty of annexation was defeated by the US Senate (the vote was 28–28, a two-thirds majority being required). The opposition was led by Senator Charles Sumner (Box 4.1), without whose intervention the proposal might have passed. The senator continued his attacks on the imperialist plans of the Grant administration even after the vote. A year later, in 1871, he addressed the Senate once again on the matter of annexation: “Over all is that other question whether we will begin a system, which, first fastening upon Dominica [the Dominican Republic], must . . . next take Hayti, and then in succession the whole tropical groupe [sic] of the Caribbean sea, so that we are now to determine if all the Islands of the West Indies shall be a component part of our Republic, helping to govern us, while the African race is dispossessed of its natural home in this hemisphere. No question, equal in magnitude, unless it be that of Slavery, has arisen since the days of Washington.”7

US interest in acquiring the Dominican Republic did not disappear after the failure of the annexation treaty. Indeed, US influence steadily advanced through the operations of the San Domingo Improvement Company controlled by American capitalists. This business acquired the financial interests of European investors in the 1890s, which in turn gave it the right to collect customs duties. As these accounted for the bulk of government revenue, it was a powerful lever—albeit in the hands at first of a private company rather than the US government.8

The Dominican Republic also signed a bilateral trade treaty in 1892, providing for tariff reductions on imports from the United States.9 Since America was the main source of imports, and since customs duties accounted for nearly 100 percent of government revenue, this contributed to the fiscal weakness of the state and its inability to service its foreign debt. In return, the Dominican Republic received a small preference in the US market for its main exports (especially sugar).10

BOX 4.1

CHARLES SUMNER (1811–74)

Charles Sumner was born in Boston, Massachusetts, and became a strong supporter of abolition in the 1830s. A founder member of the Free Soil Party, he was elected to the US Senate in 1851. His speech “The Crime against Kansas” in 1856 so outraged his southern opponents that one of them physically attacked him on the floor of the Senate two days later. Sumner nearly died and it was several years before he could return to his duties. He then became chairman of the powerful Senate Foreign Relations Committee.

Sumner had opposed the annexation of Texas, but he was not an anti-imperialist. He supported the purchase of Alaska in 1867 (but not the Danish West Indies) and sought the cession of Canada as retribution for Great Britain’s assistance to the Confederacy in the Civil War. When President Ulysses S. Grant (1869–77) came to his house unexpectedly on January 2, 1870, to seek his support for the treaty of annexation of the Dominican Republic, he did not register any opposition.

Yet he proved to be Grant’s most formidable opponent, and it is quite possible that annexation might have gone ahead without his intervention. Grant never forgave Sumner for what he saw as an act of betrayal and ensured that he was removed from his post as chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee after the vote on the treaty failed to give the president what he wanted.

Sumner’s opposition to annexation was motivated by many considerations. One was the unsavory nature of those pushing for it in the Dominican Republic itself. These included two American entrepreneurs (General William Cazneau and Joseph Fabens), who had the support of General Orville Babcock in the White House. In his famous speech of March 27, 1871, Sumner referred to Babcock as “[a] young officer, inexperienced in life, ignorant of the world, untaught in the Spanish language [Sumner was fluent], unversed in ‘international law,’ knowing absolutely nothing of the intercourse between nations, and unconscious of the Constitution of his country.”

Despite these concessions to the United States, the harbor at Samaná Bay could still not be used by the US Navy. After the failure of the annexation treaty, a New York company (assumed to be a front for the US government) had leased the facilities, but the contract was canceled in 1874 due to nonpayment. Successive US administrations then watched with some concern the entry of the German Navy into the Caribbean (the Haitian capital had been bombarded by German frigates in 1872), knowing that the US Navy was not yet in a position to respond.

Since 1823 the United States had relied on the Monroe Doctrine to guide its interests in the Americas. It had served the republic well despite the occasional breach (as when Spain had recolonized Santo Domingo during the Civil War). However, it lacked the force of international law, and there was no guarantee that the European powers would respect it. A US imperial presence in the Caribbean Basin therefore required a more muscular approach.

As the main bondholders for the independent states of the Caribbean, there was always the danger that the European powers might respond to financial turbulence by intervention. This had happened to Venezuela in 1902, when an Anglo-German-Italian fleet blockaded the main port. President Theodore Roosevelt (1901–9) had even been forced to send the US Navy to prevent German troops landing in 1903. The following year in his State of the Union address he therefore enunciated his own interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine:

If a nation shows that it knows how to act with reasonable efficiency and decency in social and political matters, if it keeps order and pays its obligations, it need fear no interference from the United States. Chronic wrongdoing, or an impotence which results in a general loosening of the ties of civilized society, may in America, as elsewhere, ultimately require intervention by some civilized nation, and in the Western Hemisphere the adherence of the United States to the Monroe Doctrine may force the United States, however reluctantly, in flagrant cases of such wrongdoing or impotence, to the exercise of an international police power.11

The Roosevelt Corollary, as it would come to be known, had far-reaching implications for the US empire in the Caribbean. Whereas the Monroe Doctrine had warned European powers against attempts at (re)colonization in the Americas, the Roosevelt Corollary spelled out the likely response to those independent states that threatened US interests in any way. In particular, countries that ran into financial difficulties could expect special attention in order to obviate the need for European intervention.

This, of course, meant dollar diplomacy.12 Debts owed by independent states to European powers would be replaced wherever possible with loans from US sources. To ensure prompt payment of debt service, the collection of customs duties would be handed to US officials. The use of the US dollar in domestic transactions would be encouraged. In extreme cases, countries would be occupied militarily by US troops. Imperial control would be exercised without the need for the formal colonial apparatus of European powers, but the US empire would nonetheless be significantly expanded.

The first country to feel the full force of the Roosevelt Corollary was the Dominican Republic. The country in 1900 had already adopted the US dollar as its medium of exchange, but had still failed to control its finances and service its debts. A US customs receivership was therefore established in 1905 without waiting for congressional approval, giving American officials control over the duties that accounted for 99 percent of government revenue. The first call on the receipts was prompt payment of debt servicing costs, ensuring that no foreign power had any reason to intervene. The balance of income was then handed to the Dominican government.13

This arrangement was formally approved by Congress in 1907 and would be renewed in 1924. It would not end until 1940, by which time the United States had been in control of Dominican customs receipts—the largest source of government revenue—for thirty-five years. The agreement even allowed up to 5 percent of the receipts to be spent to cover the costs of the US receivership itself, including the housing needs of officials.

Such an arrangement was nothing less than a protectorate. The Dominican Republic was never officially a US colony, but it had no independence in foreign affairs. Dominican politicians were left fighting for scraps, and “revolutions” were common. These sordid contests were at first of little concern to the United States. In 1913–14, for example, there were two “revolutions” that inevitably reduced the amount of revenue collected by the receivership, but debt service payments continued to receive priority, and all that changed was the amount (much smaller) handed over to the Dominican authorities.

The First World War brought an even greater involvement by the US administration in the affairs of the Dominican Republic. Although the United States was at first neutral, it could not rule out the possibility of a German invasion of the Dominican Republic. A Dominican revolution in May 1916 was therefore used as the excuse for US military occupation and the Dominican Republic now became de facto a US colony. The Dominican presidency was replaced with a military government led by a US naval officer. All this happened during the presidency of Woodrow Wilson (1913–21), who would present himself at the Versailles Peace Conference in 1919 as an anti-imperialist.

Although the Dominican political elite at first put up little resistance, this was not true of all sections of society, and armed opposition to the occupation was soon under way—especially in the east of the country. The US military therefore became involved in a brutal colonial war—no different from those fought by European powers in Africa and Asia. The guerrilla forces (known as gavilleros) were eventually crushed, but not without considerable loss of life. The counterinsurgency techniques used by US forces included scorched-earth tactics and aerial bombing.14

By 1922 resistance had been crushed, and President Warren Harding (1921–25), who opposed the occupation before becoming president, was ready to look for an exit. In what would become a familiar pattern, a supposedly nonpartisan National Guard was established and Dominicans were sent for training. In 1924 the occupation ended and a Dominican assumed the presidency, but not before the second American-Dominican Convention had been ratified. This renewed the customs receivership for a further eighteen years.15 Thus, the Dominican Republic remained firmly inside the US empire—this time as a protectorate rather than a de facto colony.

The next task for the US authorities was to choose the head of the Dominican National Guard. Their choice—Rafael Leónidas Trujillo—was to have devastating consequences. Trujillo, a fluent English speaker, understood perfectly the unwritten bargain that rulers of American protectorates were expected to make. In return for unwavering support of the foreign and defense policies of the imperial power, he would be allowed a free hand in internal affairs.16

After engineering his way into the presidency in 1930 with US connivance, Trujillo ruled the Dominican Republic as a ruthless dictator while always respecting US strategic interests. His most heinous act was the slaughter of up to thirty thousand Haitians in the west of the country in 1937. In the following year he was persuaded by the US authorities to pay $750,000 to the Haitian government in reparations (a sum reduced a year later to $525,000).17 Yet he was always warmly received in Washington, DC, and was among the first to declare war on Japan after the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

Trujillo survived the end of the Second World War and soon established his anticommunist credentials during the Cold War. For the sake of appearances, he would allow puppets to hold the presidency while maintaining full control himself. This farce satisfied US sensitivities, but eventually he overreached and became a liability. Although he was an outspoken critic of Fidel Castro, he earned the ire of President John F. Kennedy (1961–63) for trying to overthrow the democratic government in Venezuela. Trujillo’s opponents, sensing that he was losing US support, seized their chance and assassinated him in 1961.

That should have been the moment for the Dominican Republic to establish a postimperial relationship with the United States, but it was not yet to be. In 1965 the US Marines invaded in order to prevent Juan Bosch, a left-of-center politician, returning to the presidency. President Lyndon Johnson (1963–69) then helped to engineer the rise to power of Joaquín Balaguer after the marines left in 1966.18 This loyal supporter of Trujillo for more than thirty years had been the puppet president at the time of the dictator’s assassination. Balaguer, despite going blind, would be in and out of office until 1996, when he turned ninety.19

Haiti was the second country in the Americas to win its independence. It was therefore the only country for a number of years where the United States could sell its exports without facing discriminatory tariffs.20 America took full advantage of this and very quickly became the main supplier to Haiti. By 1820, when total US exports were $70 million, Haitian imports from the United States were valued at $2.25 million, so Haiti accounted for roughly 3 percent of US exports at that time.

It would have been natural, therefore, for the United States to have been among the first to give diplomatic recognition to Haiti. Yet this did not take into account the visceral opposition of the southern states, who viewed recognition as tantamount to treason in view of the success of the slave revolt in Haiti. As Senator Robert Hayne of South Carolina explained in 1825, “Our policy with regard to Hayti is plain. We never can acknowledge her independence . . . which the peace and safety of a large portion of our Union forbids us even to discuss.”21

The opposition of the southern states to recognition was also the reason why the United States failed to take part in the Congress of Panama in 1826, when Simón Bolívar invited all the independent countries of the Americas to debate issues of hemispheric importance.22 By this time, France and Great Britain had recognized the independence of Haiti, which then showed its displeasure at the United States by imposing an additional tariff on imports from America for a number of years.23 The southern states, however, would not be moved.

Relations between the United States and Haiti were therefore strained for many years. Agitation in the northern states for recognition was matched by southern contempt for the idea that commercial considerations should be given precedence over all others. Senator McPherson Berrien of Georgia stated, “These merely commercial considerations sink into insignificance—they are swallowed up in the magnitude of the danger with which we are menaced. . . . Do our brethren [northern mercantile interests] differ from us as to the danger of this intercourse? . . . Ours is the post of danger. They are in comparative safety. Who, then, should decide the question?”24 The US government then made the situation even worse by allowing a private company to seize Navassa Island off the coast of Haiti in 1857, using as pretext the Guano Islands Act of the previous year.

A change in the relationship had to wait for the outbreak of the Civil War. No longer constrained by the opposition of the southern states, President Abraham Lincoln—encouraged by Senator Sumner—was able to grant diplomatic recognition to Haiti in 1862. A commercial treaty soon followed. However, the end of the Civil War marked the beginning of a new, more aggressive, phase in US policy toward Haiti.

Haiti guarded its national sovereignty fiercely, although it failed to recover Navassa Island (it remains a US territory today).25 Having defeated the French and British in their war of independence, Haitian leaders had no intention of submitting to any foreign power. Haiti therefore resisted American efforts in the late 1880s to secure a naval base at Môle St. Nicholas, a process described by one US historian as “one of the more unsavory episodes in the history of American diplomacy.”26

Haiti incurred further US displeasure when she rejected the offer of a bilateral trade treaty in 1892. This would have given the US duty-free access to the Haitian market in return for tariff preferences on Haitian exports. However, 99 percent of Haitian government revenue came from customs duties, the United States was the main supplier, and Haitian exports (dominated by coffee) went overwhelmingly to Europe. The treaty therefore had little attraction for Haiti, but its rejection brought a harsh response when the United States imposed retaliatory duties on the main exports.

Haiti, scrupulously servicing its foreign obligations if not its domestic ones, at first escaped the full rigor of the Roosevelt Corollary when it was announced in 1904. However, the external debt was owed to French banks. In addition, some of the domestic loans were provided by German merchants living in Haiti. This raised the possibility in US eyes of foreign intervention by France and/or Germany—in defense of the creditors, but in defiance of the Monroe Doctrine. This was not a risk that US presidents would now be willing to take.

When the Banque Nationale d’Haiti27 was restructured in 1910 as the Banque Nationale de la Republique d’Haiti, the US administration therefore insisted it was done with the participation of the National City Bank of New York. This gave the United States a stake in Haitian public finance, since under the restructuring the bank collected customs duties as they were paid and passed them to the Haitian government at the end of the fiscal year (September 30).

BOX 4.2

FREDERICK DOUGLASS (1818–95)

Frederick Douglass was born in Maryland in 1818 to a slave mother and an unidentified white father. He escaped from slavery in 1838 and lived the risky life of a fugitive in the northern states until the Civil War, when he came to the attention of President Abraham Lincoln (1861–65).

After the war Douglass was in favor of the annexation of the Dominican Republic on paternalistic grounds. He wrote in his autobiography, “To Mr. Sumner, annexation was a measure to extinguish a coloured nation, and to do so by dishonourable means and for selfish motives. To me it meant the alliance of a weak and defenseless people, having few or none of the attributes of a nation, torn and rent by internal feuds and unable to maintain order at home or command respect abroad, to a government which would give it peace, stability, prosperity and civilization.”

It was no great surprise, therefore, that President Benjamin Harrison (1889–93) appointed him as minister [today ambassador] to Haiti. Unfortunately for Douglass, his arrival in October 1889 coincided with the start of the bullying campaign by the United States to acquire Môle St. Nicholas as a naval base. This put him in an unenviable position, which was made worse when Admiral Bancroft Gherardi arrived in January 1890 with instructions from Secretary of State James Blaine to secure a lease.

Douglass did his best to mediate, and warned Blaine that Gherardi’s aggressive tactics would backfire: “[Seven US men-of-war in the port] made a most unfortunate impression on the entire country. . . . Haiti could not enter negotiations without appearing to yield to foreign pressure and to compromise, de facto, [her] existence as an independent people.” When the Haitian government in April 1891 refused to give the United States what it wanted, Douglass was made to take the blame. He then resigned in July.

On October 1, 1914, the first day of the new fiscal year, the bank abruptly announced it was withdrawing from this arrangement and would not provide short-term loans to tide the government over until September 30 (as had been traditional since 1910). To ensure that the Haitian government did not seize the bank’s funds, US Marines were landed to escort $500,000 on board the USS Machias for transfer to the National City Bank of New York. The Haitian state was therefore insolvent, and political turmoil soon resulted. US troops, which had been preparing for this eventuality for some time, occupied the country on July 28, 1915.

Haiti was occupied militarily before the Dominican Republic, but the troops stayed much longer. Indeed, they would not be withdrawn until August 1934. This was in large part because of the opposition of the Haitians themselves. Although only one soldier had resisted the landing of the US Marines, there was a fierce nationalist tradition in Haiti and it was not long before resentment at the occupation was stirred up. Guerrilla forces (known as cacos) were soon in operation and their defeat was a long and bloody affair. In the first five years alone, 2,250 Haitians were killed.

The responsibility for crushing the rebels lay both with the US Marines and the Gendarmerie d’Haiti, established in 1915 by the occupying force. Rumors of human rights abuse by both soon circulated widely, so much so that the US brigade commander issued a confidential order in October 1919: “The brigade commander has had brought to his attention an alleged charge against marines and gendarmes in Haiti to the effect that in the past prisoners and wounded bandits have been summarily shot without trial. Furthermore, the troops in the field have declared and carried on what is commonly known as ‘open season,’ where care is not taken to determine whether or not the natives encountered are bandits or ‘good citizens’ and where houses have been ruthlessly burned merely because they were unoccupied and native property otherwise destroyed.”28

During the twenty years of occupation, the US authorities were responsible for most internal as well as all external affairs. It was therefore as complete an example of colonial rule as could be found anywhere in Africa or Asia, although a puppet presidency was allowed to operate alongside it.29 It even included for the first few years a system of forced labor, known as the corvée, in which peasants were obliged to work on local roads in lieu of paying a road tax.30

The Haitian-American Convention of 1915 was the key to this arrangement, as it gave the US control of public finances, security, and foreign affairs. It provided for the appointment by the United States of a general receiver and all the customs service personnel, who “should collect the revenues and apply them, first, to the expense of the receivership; second, to the service of the debt; third, to the maintenance of a constabulary; and, finally, to the ordinary expenses of the Haitian government.”31 Haiti was also forbidden to increase the debt or reduce the customs revenue without US consent.

Yet even this degree of imperial oversight was considered insufficient. The Haitian Constitution, despite various revisions, still prevented foreigners from owning land. A new constitution was therefore introduced in 1918 (Franklin Roosevelt would claim that as a young naval officer he had drafted it32) that abolished this restriction. The path was then cleared for the entry of US capital into agro-industries such as sugar, bananas, and sisal.

The Convention of 1915 was renewed for a further ten years in 1925. A series of violent strikes in 1929 then led the administration of President Herbert Hoover (1929–33) to dispatch a commission to Haiti to explore ways in which the US presence could be ended earlier than planned. These plans were well advanced when President Roosevelt took office and announced the Good Neighbor policy. The marines then left in 1934.

As in the Dominican Republic, the local constabulary took over security duties from the US Marines. However, the customs receivership continued, thereby maintaining a US protectorate in Haiti, since customs duties accounted for the bulk of government revenue. It was not until 1947, after all inherited debt obligations had been met, that the customs receivership was ended.

This long period of de facto colonial rule had a very damaging impact on Haiti, and it was exacerbated by the decision of the authorities to send southern officers to command the US forces during the occupation. The inability of these officers to make a distinction between “black” and “mulatto” among the Haitian elite—a distinction that for better or worse had played a key role in Haitian history since independence—was one of the factors behind the négritude movement in Haiti.33

Championed by Haitian intellectuals, négritude was also espoused by Dr. François “Papa Doc” Duvalier. It was one of the reasons why he was able to win the presidential elections in 1957 and provided the ideological basis for his long period of dictatorial government (he died in office in 1971). Although his brutal methods of rule were anathema to President Kennedy, he survived a half-hearted US attempt to dislodge him through skillful use of the anticommunist card.34

Haiti under Papa Doc was not a US protectorate, but it was a client state. His brutal domestic rule was tolerated on condition that he recognized and respected US hemispheric priorities. Generally he played the game. Much the same could be said about his son, Jean Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier, who succeeded to the presidency in 1971. Lacking his father’s domestic political skills, however, he was forced into exile by the military in 1986.

The United States now found itself on the back foot. A coup was no longer considered acceptable in Latin America and pressure was put on the military government to allow free elections. These were eventually held in 1990 and brought to power a radical Catholic priest, Jean-Bertrand Aristide. Not surprisingly, relations between Aristide and the military soon broke down and he was driven from office. A United Nations embargo was imposed in 1993 and President Bill Clinton (1993–2001) ordered the US Navy to Haitian waters to enforce it.35

These efforts were successful, the military fled into exile, and US troops reentered Haiti in September 1994 after an absence of sixty years. Haiti had once again become a US protectorate. This time, however, the occupation only lasted a few years while the ground was prepared for the restoration of democracy. Aristide was allowed to serve out the remainder of his term, which ended in 1996. When elections were held in 2000, Aristide then returned to power.

Any hopes that Haiti would once again become a sovereign, independent state—free from US interference—were soon dashed. Aristide’s agenda—both domestic and foreign—was considered dangerously radical by both his political opponents and the administration of President George W. Bush (2001–9). In 2004 he was forced under pressure from the United States to “resign” and fled into exile.36 This time, it was a UN Mission (MINUSTAH) rather than the US Marines that occupied the country, but it was still the United States that was in effective control.

More than a century after the 1915 invasion by the US Marines, Haiti still cannot be described as a sovereign independent state. Its problems are legion and cannot all be laid at the door of the United States. They include a degenerate political class, corruption, and widespread poverty. There have also been terrible natural disasters (especially the earthquake in January 2010). However, the United States cannot escape its own responsibility for failing to establish some semblance of normality in Haiti after such a long period of American tutelage.

Cuba early on attracted especial attention from the United States as a result of its geographic closeness, its expanding foreign trade, and—for the southern states at least—its large slave population. As early as 1823 Secretary of State John Quincy Adams had written, “There are laws of political as well as physical gravitation; and if an apple severed by the tempest from its native tree cannot choose but fall to the ground, Cuba, forcibly disjoined from its own unnatural connection with Spain, and incapable of self-support, can gravitate only towards the North American Union which by the same law of nature, cannot cast her off its bosom.”37 More prosaically, and probably more accurately, Thomas Jefferson in the same year had written to President James Monroe, saying, “I candidly confess, that I have ever looked on Cuba as the most interesting addition which could ever be made to our system of States. The control which, with Florida Point, this island would give us over the Gulf of Mexico, and the countries and isthmus bordering on it, as well as all those whose waters flow into it, would fill up the measure of our political well-being.”38

Acquiring Cuba, however, was not a simple matter. Spain, having lost all its mainland colonies by the 1820s, not surprisingly rebuffed US attempts to buy the “ever-faithful” island.39 Yet a military invasion was not realistic before the Civil War given the small size of the US Navy. Furthermore, other European powers were not willing to let Cuba fall into US hands despite their traditional rivalry with Spain. Thus, the use of force by the United States risked a war not just with Spain but with other European powers as well.

Spanish rule was increasingly unpopular on the island. Cuba’s economic expansion was used by a stagnant Spain to extract large surpluses for employment elsewhere. A resistance movement was therefore established with the aim of driving out the Spanish authorities. However, this was not at first a movement for independence—as had happened on the mainland. This was a campaign for American annexation. One of its leaders, Narciso López, even adopted a national flag that bore a striking resemblance to the Stars and Stripes.40 Ironically, it is still in use today.

US opinion was sharply divided on the wisdom of acquiring a territory with a large number of slaves. The southern states were strongly in favor, hoping that the acquisition of Cuba would eventually lead to a new slave state in the Union. The northern states, of course, were implacably opposed. The stalemate continued until the Civil War, after which the abolition of slavery in the United States made acquiring slave-owning Cuba impossible. It was not until slavery ended in Cuba in 1886 that the issue became live again.41 By then the US private sector had acquired strong interests in sugar, railroads, and mining and was pushing for a more proactive US policy.

By the mid-1890s the US administration still had little to show for all its imperial efforts in the Caribbean. A few unoccupied islands had been acquired under the Guano Islands Act;42 the McKinley Tariff Act of 1890 had been used to sign bilateral trade treaties with Spain and the United Kingdom (on behalf of their Caribbean colonies) and with the Dominican Republic that gave privileges to US exporters.43 US capital was invested in the larger islands, but only in the Dominican Republic could it be said to be dominant.

All this would change soon after the outbreak of Cuba’s Second War of Independence (1895–98).44 Spain, the colonial power, was struggling to crush a revolt which rapidly spread to Puerto Rico (its other Caribbean colony) and which this time was aimed at independence (not annexation). The temptation in Washington, DC, to intervene was strong, and the “mood music” in the country had changed. Imperial ambitions were now openly on display and much of the press was clamoring for war. All that was lacking was the casus belli.

That came with the sinking of the battleship USS Maine in February 1898.45 The United States declared war on Spain and victory swiftly followed. Cuba and Puerto Rico were occupied militarily. At the peace negotiations in Paris, the nationalists were excluded despite their heroic sacrifices. The United States secured the cession of Puerto Rico, which then became a US colony (its first in the Caribbean) with a governor and all the other apparatus of imperial rule (its name was even changed to Porto Rico to ease pronunciation by the new colonial masters).46

Many predicted that Cuba would follow the same path. This, after all, is what Jefferson and Adams had called for almost a century earlier, and the imperial logic had not changed. Indeed, it was what many inside and outside Congress demanded. However, there was an insuperable obstacle in the form of the Teller Amendment. This had been passed by the US Congress in April 1898 at the time war was declared on Spain, and it ensured that Cuba would become nominally independent rather than a formal US colony.

Henry Teller, a Republican senator from Colorado, was no anti-imperialist. However, among other motives, he recognized the danger that a Cuba inside the US tariff wall would represent to the domestic sugar industry (by this time present in almost half the continental states). Coping with competition from Puerto Rico or Hawaii was one thing, but Cuban sugar was a whole different story. One of the lowest cost producers in the world, Cuba could have wiped out not just cane sugar in Florida, Louisiana, and Texas, but also beet sugar in other states (beet sugar is a perfect substitute for cane sugar, and Teller was from a beet-producing state).

Thus, Cuba would become “independent” after four years of military occupation that brought huge advances in health, sanitation, public works, and education. Indeed, it was in many respects a colonial interlude of which any European imperial country would have been proud. Havana Harbor was cleaned up, mortality rates dramatically reduced, and public finances put on a more sustainable keel. Yet it was an independence that was subject to such onerous conditions that Cuba in reality became a US protectorate, the model for many others in the future.

These conditions were laid out in the Platt Amendment, introduced to Congress by Senator Orville Platt (Box 4.3) in 1901 and passed by a vote of 43–20 (it had in fact been drafted by Secretary of War Elihu Root). It established eight conditions that Cuba had to accept before the US military would be withdrawn and independence declared. Article 3, for example, stated: “The Government of Cuba consents that the United States may exercise the right to intervene for the preservation of Cuban independence, the maintenance of a government adequate for the protection of life, property, and individual liberty, and for discharging the obligations with respect to Cuba imposed by the Treaty of Paris on the United States, now to be assumed and undertaken by the Government of Cuba.”

BOX 4.3

ORVILLE PLATT (1827–1905)

Orville Hitchcock Platt was born to a farming family in Connecticut in 1827. His parents were abolitionists, and the son inherited their views. He cast his first vote for the Free Soilers before joining the Know Nothing Party in the 1850s. Later he joined the Republican Party and played an important part in Connecticut state politics during and after the Civil War.

He first entered the US Senate in 1879 and was a strong supporter of tariff protection for domestic manufacturing. More significantly, he was a member of the Senate Committee on Territories from 1883 to 1895 and chaired it for six years, from 1887 to 1893.

These were the years when the expansion of the US empire into the Caribbean was very much on the agenda. Platt was a strong supporter of the Spanish- American War in 1898 and favored the annexation of Hawaii, the Philippines, and Puerto Rico. He also welcomed the idea of absorbing Cuba, but the Teller Amendment required an alternative to formal annexation.

Platt’s solution, although he did not draft it, was the amendment that bears his name. Its eight articles systematically robbed Cuba of any possibility of becoming a sovereign independent country. When the Cuban Congress was forced to absorb the amendment into its 1902 constitution, it made it very difficult to change.

Article 7 allowed the United States to choose Guantánamo Bay for one of its naval bases in Cuba. Although some of the articles of the Platt Amendment were repealed in 1934, the United States negotiated a new treaty with Cuba allowing it to keep Guantánamo Bay provided that it was used only for its original purpose.

If Article 3 gave the United States a blank check to intervene at will, Article 7 paved the way for the all-important naval bases that had eluded the United States for so long. It stated that “to enable the United States to maintain the independence of Cuba, and to protect the people thereof, as well as for its own defense, the Government of Cuba will sell or lease to the United States lands necessary for coaling or naval stations, at certain specified points, to be agreed upon with the President of the United States.” 47

The Cuban Assembly, despite being a largely supine body during the military occupation, was so offended by the Platt Amendment that it initially voted against the conditions. When it became clear that US forces would not withdraw, the assembly changed its mind and the amendment was incorporated into the new Cuban Constitution without a word being altered. Within a year, the United States had selected its preferred sites for coaling and naval stations. They would include Guantánamo Bay.48

US forces left in 1902, independence was declared the same year, and Cuba became the first Caribbean country since the Dominican Republic in 1844 to escape formal colonial control. However, its sovereignty was heavily restricted. This was demonstrated not only by the Platt Amendment but also by the Cuban-American Treaty of 1903, which gave the United States a wide range of tariff preferences in the Cuban market in exchange for duty reductions for raw sugar and tobacco imports. This paved the way for the massive entry of US capital, and a new sugar boom was soon under way on the island.

As a protectorate, Cuba was now firmly in the US orbit. However, as many European powers had found in their own informal empires, protectorates could still be very troublesome. US troops were back in Cuba in 1906 when election results were disputed, and they did not leave until 1909. Three years later they were back again to help put down an insurrection sparked by the suppression of the Partido Independiente de Color, a movement started by black veterans of the Second War of Independence in protest against discrimination. The tradition in which the US authorities would become the arbiter of domestic political disputes in Cuba was now well established.

After FDR outlined the Good Neighbor policy, optimists could argue that Cuba was no longer a US protectorate. However, this was not true, as the United States retained Guantánamo Bay and a revised Cuban-American Treaty in 1934 still gave America special privileges.49 In addition, US sugar policy toward Cuba had changed, and this crucial export was now subject to quotas that could be raised or lowered according to US whim.50 In any case, the dominant position of the United States in domestic politics was very quickly demonstrated.

The US ambassador to Cuba (Sumner Welles) found himself in 1933 in conflict with President Gerardo Machado, whose term of office was due to expire in May 1935. Machado had been favored by US officials in the 1920s, and this had helped him to retain the presidency under dubious circumstances. However, he had now outlived his usefulness and had become increasingly discredited.

Welles negotiated with the Cuban army for intervention against Machado, and he was duly ousted from office in August 1933. His successor (Carlos Manuel de Céspedes), however, was too weak to deal with the numerous social conflicts that arose in the wake of the Great Depression. This had hit Cuba very hard, and the result was a series of strikes and protests that became increasingly radical.

The protests included sections of the armed forces themselves. A barracks revolt, led by Sergeant Fulgencio Batista, unleashed a series of events that resulted in the fall of the government. A provisional government was then formed, led by Ramón Grau San Martín, an intellectual and a respected figure in Cuban political life. He promised to establish a modern democracy and launched a number of social reforms.

This was too radical for Sumner Welles, and US recognition of the government was withheld. This guaranteed that Grau San Martín’s presidency would be short-lived. Welles then encouraged the Cuban Army—now led by Batista—to intervene. Batista instantly became the “strong man” of Cuban politics, ruling either through a series of puppets, albeit elected, or as president himself until his flight from Cuba on January 1, 1959.51

His reward for overthrowing the Cuban government in 1934 and installing a new president was US recognition of his regime. Cuba was still a protectorate and Batista, like the other dictators in the Caribbean, understood that in order to retain power he had to protect US interests. The US protectorate over Cuba only ended with the Cuban Revolution, which helps to explain the ferocity with which Fidel Castro’s government was greeted by the administration of President Dwight D. Eisenhower and subsequent administrations.

Puerto Rico was annexed in 1898, but it was a few years before its constitutional status would be clarified. The American military authorities on the island, unsure of the final status, began by lowering (but not eliminating) the tariff on imports from Puerto Rico into the United States. The Organic Act of 1900, sponsored by Senator Joseph Foraker, was then passed; it was similar to that for the Philippines. This left Puerto Rico as “unincorporated,” meaning it had no right to statehood. The Foraker Act provided for a locally elected House of Delegates, but a US-appointed upper chamber and governor.52

Puerto Rico came fully inside the US tariff wall in 1902 (this was a decade before the Philippines). No duties or quotas would now be applied to goods exported from the island to the United States. This gave export industries an advantage over competitors in the Caribbean. An export boom then commenced and within a few years virtually all trade was with the United States.

Puerto Rico was now a US colony. Federal taxes were not applied to the island, but customs duties raised very little (almost all trade was with the mainland) and budget subsidies from the mainland were nonexistent. The island therefore suffered from the problems common to many colonies. However, under the 1917 Jones Act Puerto Ricans became US citizens (this never happened in the Philippines). This did not give them the right to vote in US elections, but it did give them unrestricted entry to the United States.53 The Jones Act also provided for a locally elected upper chamber.

The colonial government, anxious to avoid the emergence of a strong US lobby in favor of statehood, at first restricted the size of landholdings to five hundred hectares.54 However, this was quietly ignored when it became clear that it was an obstacle to the expansion of sugar exports. Duty-free access to the US market for sugar had a spectacular impact and US capital poured into the island.

Unfortunately for Puerto Rico, it was too successful. When the crisis of the world’s sugar industry reached a climax in the Great Depression, the island was obliged to make a major sacrifice. Under the 1934 US Sugar Act, the island kept its duty-free access but lost its quota-free position. The sugar industry therefore lost its dynamism, unemployment soared, and migration to the United States—especially New York City—accelerated.

This was the moment when Puerto Rico’s colonial status nearly ended. Senator Millard Tydings, who had sponsored the bill in 1934 that provided for the eventual independence of the Philippines, tried to do the same for Puerto Rico in 1936. Many Puerto Ricans supported the bill, although none had a vote, but the political class on the island was divided. Senator Tydings then withdrew his bill. The main opponent of independence was Luis Muñoz Marín, who would go on to form the Partido Popular Democrático (PPD) and become the first elected governor in 1948.55

The decision of the US government in the Second World War to return to Puerto Rico the federal excise duties collected on rum exports gave a big boost to the island, as it coincided with the wartime switch on the mainland from whisky to rum consumption.56 It also provided the resources for a colonial experiment in state-owned enterprises (the Puerto Rican Development Company and Development Bank). Although implemented by the local Puerto Rican government, the experiment was the brainchild of the colonial governor.

Encouraged by the results, Puerto Rico adopted Operation Bootstrap after the Second World War with spectacular results. Boosted by local fiscal incentives and the absence of federal taxes, manufacturing on the island soared and Puerto Rico became for many a model of development. Sir Arthur Lewis, whose work on development economics earned him a Nobel Prize, was particularly enthusiastic.

As had happened with sugar, the experiment was too successful. The impact of fiscal concessions on the US federal budget became too large, and they started to be withdrawn in the 1990s (Box 4.4). The result was a decline in manufacturing on the island and a big increase in unemployment and net outward migration. Those who previously looked to Puerto Rico as an inspiration for the Caribbean started to look elsewhere.

Puerto Rico is now in limbo and bankrupt. A majority says it wants a change in the island’s constitutional status. Yet only a small minority favor independence, as it would mean losing both federal welfare benefits and unrestricted access to the United States. There is for the first time a majority in favor of statehood, but no certainty that it can be achieved, as the decision can only be taken by Congress.57

Puerto Rico became a US colony as a result of war. The US Virgin Islands, on the other hand, became a dependency by a very different route. Secretary of State William Seward had returned from a tour of the Caribbean after the Civil War enthused by the idea of acquiring the magnificent harbor at St. Thomas in the Danish West Indies.58 An attempt was made by the US government to purchase the three islands from Denmark in 1867. It looked as if it would meet with success (the Danish Parliament had voted in favor), but the treaty was rejected by the US Senate in 1870.59

Embarrassing though it was, this would not be a major blow to the US government. By the end of the century Cuba had been turned into a protectorate and Puerto Rico had become a colony. The occupation of Haiti (1915) and the Dominican Republic (1916) then left the United States in a dominant position in the Caribbean.

BOX 4.4

CARIBBEAN COLONIES AND US FISCAL POLICY

By the beginning of the twentieth century, the US economy had become so large in relation to all Caribbean colonies that any change in US fiscal policy was bound to have a major impact. This was true not just for the US colonies/protectorates but also for the European colonies.

When the United States eliminated its sugar tariff for Puerto Rico in 1901 and lowered it for Cuba in 1903, it led to a sugar boom on the two islands. It also led to trade diversion away from the British colonies that had previously supplied the United States with much of its needs. These colonies then shifted exports to Canada, taking advantage of the recent introduction of imperial preference there.

The 1919 Prohibition Act in the United States effectively imposed an infinite tariff on rum imports. Suddenly, St. Pierre and Miquelon—two tiny French islands at the mouth of the St. Lawrence River—became major destinations for exports from numerous Caribbean islands. From there alcoholic drinks entered Canada legally before being imported as contraband into the United States. The Virgin Islands, on the other hand, turned the alcohol into bay rum in order to stay within the law.

The decision by the United States to return the excise duty on rum consumption to the US colonies (1954 for the Virgin Islands, earlier for Puerto Rico) not only boosted the industry but also damaged exports from other Caribbean countries. When the Virgin Islands started to use the funds in 2010 to subsidize the operations of multinational enterprises manufacturing spirits, the other Caribbean countries launched a claim against the United States at the World Trade Organization.

When federal tax exemption became available for the operations of US companies in Puerto Rico after the Second World War, manufacturing boomed and reached 50 percent of GDP (twice the US ratio). However, when the tax breaks were phased out during the administration of President Bill Clinton (1993–2001) it had a crippling effect. Only the pharmaceutical companies, still allowed to write off their research and development expenditure on the mainland against their profits on the island, were able to survive.

France and Great Britain controlled most of the other islands, and the United States had little to fear from them. When the First World War broke out in August 1914, America remained neutral. The security of the Panama Canal, opened to international traffic in the same month as the war started, therefore appeared assured to the strategists in Washington, DC.

There was still, however, one weak link: the colonies of the neutral European powers. Neither Denmark nor Holland had gone to war in 1914, and both controlled islands that were either close to the US mainland or to the Panama Canal.60 If Germany should invade Denmark or Holland, these islands could fall into the hands of a potential enemy. In particular, the United States was conscious of the risk that the Danish harbor of St. Thomas—perhaps the finest in the Caribbean for naval purposes—might become a base for German submarines.

Thus, President Wilson was persuaded to return again to the vexed question of the transfer of sovereignty of the Danish West Indies. This time, however, the matter was urgent and negotiations were concluded quickly. The price ($25 million) was much higher than suggested before, but that was now immaterial. By the end of March 1917, just before US entry into the First World War, the Stars and Stripes had replaced the Danish flag on the territory that would be known as the US Virgin Islands.

The United States now had two Caribbean colonies, but their administration was very different.61 The navy was put in charge of the Virgin Islands until 1931 in recognition of its maritime importance. This led, however, to some strange decisions such as the navy chaplain in 1924 being put in charge of the newly established Department of Agriculture. And colonial governance was not helped by Prohibition (1919–33), since it crippled one of the main industries on the island.62

Duty-free access to the US market for the islands’ sugar from 1917 onward did not have the anticipated effect, so the authorities conducted an unusual colonial experiment.63 This was the creation in 1934 of the state-owned Virgin Islands Corporation with the power to control all aspects of the sugar, rum, and molasses industries and later branching out into banking, tourism, and public utilities. It was an experiment that the British would later copy in some of their African colonies, although state control was never taken as far.

By the end of the 1930s the United States had consolidated its empire through its two colonies and its three protectorates over the “independent” states of the Caribbean. However, that still left the European colonies. Great Britain, France, and Holland between them controlled all the smaller islands (except the US Virgin Islands) as well as the littoral territories of Belize (British Honduras) and the three Guianas.

All three European powers adopted commercial policies that favored the exports of their own companies to their colonies.64 This was standard among imperial powers. Indeed, the United States did the same with its Caribbean colonies, with Cuba (through the reciprocity treaty), and with Haiti and the Dominican Republic through the customs receiverships (tariff revisions invariably favored US exporters). However, the State Department under Cordell Hull became increasingly irritated with the imperial preference of the European powers, as it ran counter to US efforts to liberalize trade in the 1930s.65

This irritation led to a bilateral treaty with the United Kingdom in 1937 to ensure that US firms had the same access to Caribbean colonies as British companies. It also meant that US firms could export from these colonies to the United Kingdom without fear of discrimination. At the same time, the Dutch colonies were becoming increasingly important for US strategic needs as a result of the oil refineries on Aruba and Curaçao and the bauxite deposits in Suriname. US investments therefore started pouring into the British and Dutch colonies (the French ones would remain impenetrable).

The new modus vivendi between the European and American empires in the Caribbean was disrupted by the outbreak of the Second World War in September 1939. No longer could the United States assume that the European powers would take care of security in their colonies. In particular, the Panama Canal could be under threat if hostile forces acquired any of the territories in the region.

The invasion of France and Holland by Germany in June 1940 dramatically raised the stakes. The Dutch Caribbean territories remained loyal to the government in exile, but had no means of defending themselves in the case of attack. The French Caribbean colonies declared their allegiance to the Vichy government and were therefore vulnerable to German pressure. The United Kingdom survived the Battle of Britain, but was increasingly desperate for materiel with which to conduct the war.

The result was an enormous expansion of the US imperial presence in the region even before American entry into the Second World War. Troops were dispatched to the Dutch colonies to protect the oil refineries and bauxite mines, while no trade was permitted with German-occupied Holland. Naval vessels patrolled the seas off the French colonies to ensure there was no trade with Vichy France or Germany. For the first time ever, the United States became the main trade partner for these territories.

Military bases were leased for ninety-nine years from Great Britain on several of its Caribbean colonies in return for US destroyers. The local population was not consulted, and the arrival of US armed forces was to prove controversial. In Trinidad & Tobago, the base inspired a famous calypso song (“Rum and Coca Cola”) whose second and third verses left little to the imagination.

When the United States entered the war in December 1941, it therefore had all it needed in the Caribbean to protect its interests. An Anglo-American Caribbean Commission was established in 1942 to deal with wartime issues. France and Holland joined in 1946 to participate in postwar planning. This was a conscious effort by the empires to establish the framework for continuing imperial control of the Caribbean. Not much attention was paid to local aspirations, much to the disgust of Eric Williams (the first prime minister of Trinidad & Tobago) who worked for the commission during the war.66

Until the end of the 1950s, the United States had every reason therefore to assume its empire in the Caribbean was secure. However, the Cuban Revolution was a major challenge to US authority. Cuba was by far the most important country in the region and its “loss” harmed the prestige of the United States in many ways. Just as damaging, however, were the policies adopted by America against Cuba even after the threat to national security had passed.67

The US territorial empire in the Caribbean has not ended (there are, after all, two colonies) and the United States has continued to intervene occasionally by force.68 However, American imperialism takes a different form—not just in the Caribbean but in other parts of the world as well—and the territorial empire is no longer so important. How this transformation in the American empire took place is the subject of Part II.