TWO

The Unexpected Consequences of Advancing Technologies

CHAPTER SUMMARY: After touching on our understanding of the broad influences on technology adoption, this chapter discusses how primary (first-order) disruptions usually lead to second-order disruptions, including new business models and new means by which businesses, governments, and nonprofits can interact with customers. The chapter also offers a glimpse into the “Hall of Toast” through a series of case studies and analyses documenting how once high-flying companies have gone astray when faced with disruptive technological shifts.

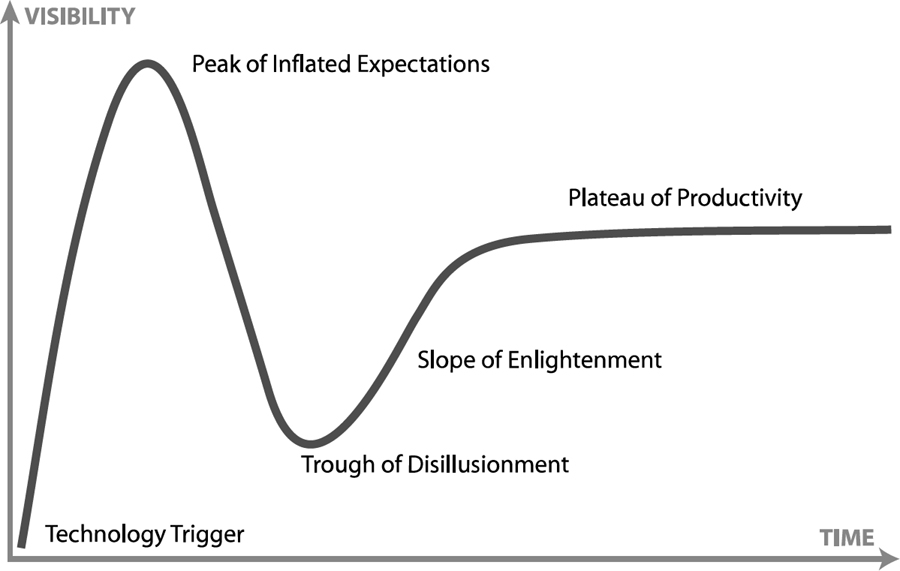

In 1995, the American research, advisory, and I.T. firm Gartner created a concept it called the Hype Cycle (Figure 2.1).1 Broadly adopted and embraced since by the business and analyst community, the Gartner Hype Cycle is a model showing rough timelines and stages in the maturation, adoption, and social application of technologies. Though it has been deprecated as inaccurate and lacking a basis in evidence, the Hype Cycle does provide a useful framework for thinking about technology adoption.

Figure 2.1. The Hype Cycle model for technology adoption created by technology research and analyst company Gartner, Inc.

Source: Gartner, Inc. (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Hype_cycle#/media/File:Gartner_Hype_Cycle.svg)

In the field of V.R., for example, there was enormous hype (the “Peak of Inflated Expectations” in the Hype Cycle) leading to breathless predictions about people living most of their lives in virtual environments, followed by caustic articles (the “Trough of Disillusionment”) about early-generation V.R. goggles making people seasick. Now we appear to be moving up the curve’s “Slope of Enlightenment” as applications of V.R. gear are emerging and people who are not early adopters are using them to do nifty things such as sit “courtside” at professional basketball games in the United States. In the very near future, we will hit the curve’s “Plateau of Productivity”—the point at which V.R. has become part of everyday life and is no longer rare or unusual. Among smartphones, the iPhone brought us to this point; among computers, the Mac and Windows computers did. A useful test of whether a technology has hit this point is whether something “just works” with almost no effort or learning curve—in the way in which an experienced user of earlier mobile phones can pick up an iPhone and immediately understand how to operate it.

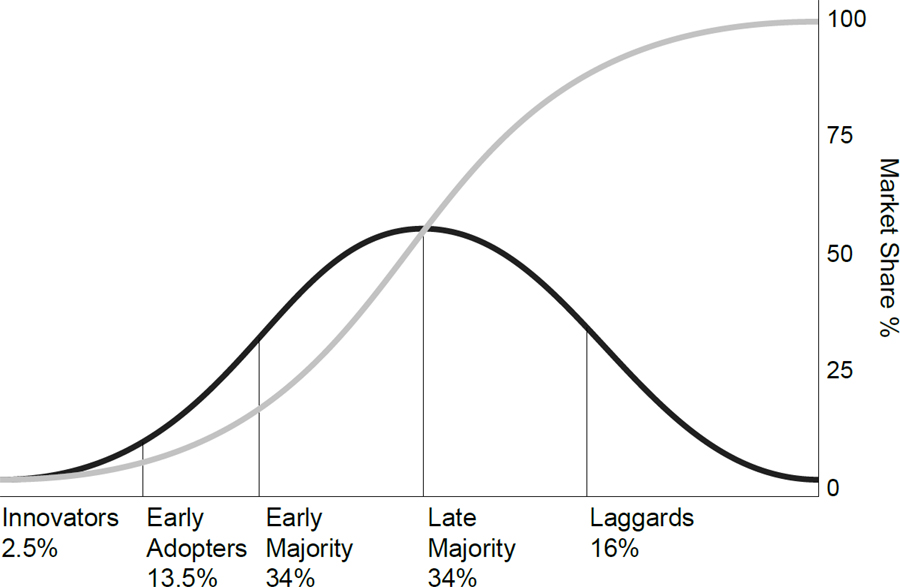

Figure 2.2. Rogers’s Diffusion of Innovation Model. In his 1962 book Diffusion of Innovations, Everett Rogers popularized the theory that explains how, why, and at what rate new ideas and technology spread.

Adapted from Everett Rogers, Diffusion of Innovations, London and New York: Free Press, 1962 (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Diffusion_of_ideas.svg)

A more robust (albeit drier) model of technology adoption is Everett Rogers’s Innovation Diffusion Model (Figure 2.2).2 The model attempts to explain why, how, and at what pace new technology and innovation spread. Rogers, a communications professor, first published this idea in a book in 1962. He takes a social contagion approach to innovation diffusion and technology spread, asserting that diffusion consists of four primary elements: the innovation itself; communication channels; time; and a social system. He posits that, in order to become self-sustaining, innovation must be widely adopted. He divides the adopters into five categories: innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggards—the same categories that Geoffrey Moore uses in his iconic business book, Crossing the Chasm.

From First-Order to Second-Order Disruption

Ever since the publication of Rogers’s work, innovation researchers, technologists, and businesses have studied innovation adoption as a trajectory along an S-curve. With more recent innovations, technology-adoption curves have looked more like straight lines with a small bend in the middle. You may have to squint to see the S-curves on it, but the graph in Figure 2.3 shows the adoption curves of major technologies over the past century. To the left side of the graph are earlier technologies, such as the telephone; to the right appear more recent ones, such as the smartphone and the tablet. Moving from left to right, the curves clearly rise more steeply and more consistently, indicating the increasingly rapid pace of technology adoption. Plots of the adoption of smart speakers and V.R. would have looked steeper still.

The acceleration in adoption of newer technologies is evidence of what we may call second-order disruption arising from breakthrough innovations. When multiple fast-moving (or exponentially advancing) technologies merge into one product class, the result is even faster development and improvement. Naturally, faster development and improvement mean faster maturation, which in turn generates swifter adoption.

Figure 2.3. Accelerating Pace of Technology. Adoption rate of new technologies over time with adoption curves steepening (adoption growing more rapidly) from left to right.

Source: Our World in Data, https://ourworldindata.org/technology-adoption.

Let’s consider a few technologies in this light. The telephone, which proved to be a revolutionary device, used a single innovative technology—the conversion of electrical signals into sound and vice versa. The smartphone was a far more powerful technology. It incorporated a number of key legacy technologies—camera, telephone, typewriter, maps—and included overlapping exponentially advancing technologies, such as semiconductors, software, geolocation, and cheap sensors. Whereas the telephone is useful for communication, the smartphone, incorporating many exponentially advancing technologies, quickly became a tool without which many of us would be incapable of managing our lives—as well as one that consumes an ever-growing portion of our time.

The smartphone is today the dominant technology platform and continues to replace discrete devices and services at a voracious pace. Smartphones now carry the software and sensor equivalents of dozens of discrete consumer electronic devices, each representing a formerly lucrative and substantial market: the camera, the tape recorder, the telephone, the turn-by-turn GPS unit, the blood-oxygen sensor and heart-rate monitor, the fitness tracker, the stopwatch, the electronic (and physical) tape measure, and the DVD player. The list continues to grow as our phones gain utility via faster, more powerful computers and a wider array of cheap yet accurate sensors.

Until recently, however, the smartphone did not have a way to recognize complex patterns in the myriad data now appearing in our digital lives. This explains in part why Alexa and Amazon’s voice services have taken off so quickly: they combine not only a useful range of exponential technologies but also well-designed predictive and pattern-matching software in the form of A.I. As machine learning becomes increasingly embedded into the technology we use, it will evolve faster and improve more quickly. A case in point is Tesla: the fact that it is both a car company and an A.I. company improving its systems and software using data gathered as its vehicles use the road is what underlies the company’s ability to make the Tesla experience so magical.

The accelerating pace of innovation leads, unsurprisingly, to more opportunities for industry disruptions. A case in point is package delivery.

A Case Study in Exponential Disruption: Package Delivery

Delivery fleets have traditionally required planes, large trucks, boats, trains, and final-hop vehicles such as delivery vans, cars, and bicycle couriers. Buying or leasing the infrastructure for such a network was very expensive and capital intensive; and creating software to manage these networks required constantly updated map data, traffic information, and logistics and planning capabilities. Clearly those barriers have begun to fall: Uber, Lyft, Postmates, Deliveroo, and Grubhub have all either taken advantage of extant geolocation and mapping capabilities, logistics and dispatching software, and pricing algorithms or built their own—and have reached a nearly global scale in their first five years.

With the Federal Aviation Authority’s approval of drones for delivery, the entire package-delivery model is about to receive an upgrade. Drones have tremendous advantages over cars and trucks: they have zero emissions; they never get stuck in traffic; they have a smaller form factor; and they don’t require an accompanying human. Also, their cost is plummeting, and consumer-grade technology almost meets the requirements of commercial drones. (Drones are like smartphones with rotors. They use the same chips, sensors, and connectivity mechanisms.) And, whereas a Sprinter-style delivery van costs $50,000 or more, the cost of the latest iteration of self-flying autonomous drones has fallen below $1,000.

The use of drones fundamentally alters the pattern of goods transportation, ripening the market for innovation and exploration both by startups and by the faster-moving of the legacy companies. Drone development represents second-order innovation, having benefited from a confluence of smaller and cheaper computers, smaller and much cheaper sensors, essentially free geolocation data, and ubiquitous broadband connectivity. Drones may also alter the way factories work, by providing flying visual quality control and process analysis without the need to install and wire cameras at every corner of a production line: a flying version of Industry 4.0.

Faster technology development is a blessing and a curse for legacy companies: they have the resources to invest sooner than others in a technology, but their greater inertia tends to delay early adoption. An organization’s ability to forgo overly rigid structures and hierarchies and to embrace change in how people work and think, remaking itself as needed, makes it more agile and less fragile than otherwise. The leaders of such organizations trust their smart employees to lead the way. And their CEOs ensure that their companies spend organizational, financial, and intellectual capital wisely: either on creating new business lines or on reinventing the future of existing business by rapidly adopting better technologies—even if those technologies may be unprofitable at first. In some scenarios, allowing spin-offs to chase innovation is a wise strategy. RCA, for instance, was spun off from General Electric in order to comply with U.S. antitrust laws.

For those organizations unable to adapt or change to embrace innovation, the Hall of Toast awaits.

The Hall of Toast and Modern Disruptors

Technology is obviously disrupting the status quo in business. Unsurprisingly, this is showing up in company balance sheets. Since 1935, the average duration of membership in the Standard & Poor’s 500 has fallen from 90 years to less than 20 years, and it continues to fall. At the current rate of turnover, a full 75 percent of the current S&P 500 will be replaced in less than a decade. The majority of those that are pushed out of the S&P 500 will ultimately be consigned to oblivion or be snapped up by rivals or up-and-coming brands.

Companies that have fallen include iconic brands such RadioShack, Sears, Compaq, Yahoo, and Dell EMC. Others that may be on the way out include Hewlett-Packard, Gap, and Kraft Heinz. Still other giant brands have been subsumed, including Jaguar, Land Rover, Chrysler, Whole Foods, and America Online. Few remember any longer that RCA (Radio Corporation of America) was a dominant player in the market for early consumer electronics in radios and televisions through the 1970s and, in its day, boasted the most innovative productive invention labs in the world.

The Hall of Toast is replete with once-amazing legacy companies that failed to adapt quickly enough to exponential technologies on the horizon—even when they themselves had introduced the disruptive technologies. The classic Hall of Toast example is the camera and film company Kodak, which, founded in 1888, employed, at its peak, more than 120,000 people and was one of the most valuable companies in the world.

To its credit, Kodak had aggressively pursued smart research and development. In 1987, Kodak entered the “filmless” (or digital) camera market and later created a number of products for digital photography. Wall Street thought that the company could do no wrong, tripling Kodak’s share price even as the company announced cost-cutting plans with increasing frequency. The cash-cow film business afforded Kodak tremendous latitude. That, along with a lack of real commitment by Kodak’s managers to the digital future, led to poor performance in digital products. Internally, Kodak’s nascent digital unit had the status of an ugly stepchild. Yet the handwriting was clearly on the wall: electronic photography would replace film photography.

What spelled Kodak’s death knell was the rise of the smartphone and cheap, good digital cameras. Film photography dominated the market right up until 2000. A few years later, film photography commenced a rapid decline. By the time Kodak filed for bankruptcy in 2012, digital photography was used more than 90 times as often as film; in that year, when roughly 380 billion digital photographs were shot, only 4 billion frames of still film were exposed.

This is the reality, too, of exponential growth curves. As Ray Kurzweil likes to point out, on an exponential curve, reaching a mere 1 percent adoption from 0.01 percent puts you halfway to 100 percent. With digital photography, as if someone had flipped on a light switch, suddenly the technology was better, cheaper, and more convenient. The demise of film—and of Kodak—was swift. Had Kodak understood that it was facing an exponentially growing product category, it might have met the challenge.

From Xerox, the original creator of the graphical user interface, to networking pioneer 3Com, to fast-fashion pioneer Forever 21, which declared bankruptcy in late 2019, the Hall of Toast is haunted by the ghosts of companies that once were hailed and later failed or shrank to a shadow of their former selves. As we were writing this book, the 170-year-old travel agency and travel-services company Thomas Cook, struggling to compete with Internet agencies, abruptly went bust, leaving thousands of travelers stranded and unable to return home.

Survival: An Endless Task

Staying out of the Hall of Toast is a never-ending task. Technology giant IBM started making office equipment, then smartly pivoted to computers, and then pivoted again to technology services and software, all under the guidance of legendary CEO Louis Gerstner. Gerstner initiated a formal process for creating innovative business at IBM, one that worked quite well, and IBM Life Sciences emerged from that rigorous process. But later managers dismantled Gerstner’s business-innovation programs, and IBM has struggled to switch from technology services and the servers and boxed-software licenses in declining demand to cloud computing and other areas experiencing faster growth.

Facing multiple quarters of declining revenues, IBM responded by slashing its workforce. Even so, IBM is investing far less in necessary capital expenditures than its rivals are, and risks heading for the Hall of Toast—unless it makes another urgent course correction, which we hope it will.

Certainly, IBM’s managers are aware of the risk. Under the guidance of new CEO Arvind Krishna and with the approval of outgoing CEO. Virginia Rometty, IBM made a “bet-the-company” acquisition in 2018, purchasing cloud computing and Linux giant Red Hat for $33 billion. This came after IBM had failed to internally jumpstart a viable cloud business, and after IBM’s initial foray into A.I. with Watson resulted in lower revenues than anticipated and less in stalled technology progress in key sectors such as health care. Krishna is a very smart engineer, and the logic of the acquisition makes sense; but for IBM to truly avoid the Hall of Toast, the company will need to change its culture yet again to imbue the more nimble ethos of Red Hat and the faster metabolism of cloud computing into all it does.

Exponential trends can overwhelm even well-intentioned efforts to innovate. Gannett, the giant U.S. publisher of newspapers and operator of television stations, made strong efforts to innovate, but it has thus far failed to overcome the downdraft that has plagued both print- and, to a lesser degree, broadcast-advertising markets. Its share price having fallen 89 percent from its all-time peak in 2004, Gannett is in the process of merging with a cut-rate operator of media companies.3 With the company that controls Gannett largely focusing on cost-cutting rather than on innovating to squeeze out more revenue, the one-time dominant force in the U.S. newspaper market, too, appears to be heading for the Hall of Toast.

Critical to understanding the forces consigning so many legacy leaders to oblivion is appreciating the effect of some recent disruptions in a range of key industries and even in government. In those disruptions lie the key insights for returning legacy companies to innovator status using the same techniques as the upstarts.