Chapter 9

General Gough had already ordered his car and, shortly after General Humbert took his departure, he set off to visit his four Corps Headquarters. It would entail a round trip of more than sixty miles on narrow country roads which had never been meant for fast travel, and he would be away from his telephone for at least three hours, but it was a risk that he felt obliged to take. Before leaving, he took the precaution of telephoning each of his four Corps Commanders in turn to ascertain the present situation.

It was almost 3.30 before he breezed into III Corps Headquarters at Ugny-le-Gay, deliberately showing a cheerful front to General Butler and his staff. It was Butler’s first engagement as a Corps Commander, and his line on the extreme right of the Fifth Army was seriously threatened. The enemy had penetrated across the River Oise on his 58th Division front. The Buffs at Vendeuil had actually seen a contingent of German soldiers marching north on the St Quentin road, passing between their outposts half-hidden in the mist. But, although much of the outpost line had now been lost, the 18th Division was still fighting on in its battle zone. The trouble was on their left, where the flank of the 14th Division had given way.

Gough did not allow himself to show dismay. He merely confirmed the order he had given earlier: that III Corps was to pull back, as previously arranged, to the line of the Crozat canal a little way behind. But he impressed on General Butler that it must be no haphazard retirement, and that the troops should keep in touch with the troops to right and to left. The afternoon was wearing on, and in two hours the light would start to fail and the fighting would surely abate; until then he was confident that III Corps would not give way. The 3rd Cavalry Division had already been ordered to move south to support them, and General Humbert had promised to do everything in his power to persuade General Pétain to keep his promise to send French troops to their assistance. Gough was sure that Pétain would do so. He left his Corps Commander feeling a good deal less anxious and a great deal more cheerful than he felt himself.

It was just fifteen miles from Ugny to XVIII Corps outside Ham, where General Maxse had set up his HQ near the canal. His battle zone was still unbreached, although he had taken heavy casualties in the outpost line and the flanks of the battalions on his right and on his left were ‘in the air’. He was, nevertheless, absolutely certain that his troops could hold on – and they were holding on, even in the outpost zone at Manchester redoubt, at Enghien redoubt, at Holnon Wood and on Holnon plateau, where they had thrown back a flank to protect the battle zone from being entered from the north. But his force was seriously weakened. It was self-evident that Maxse would be forced to pull back his flanks to keep in touch with the troops on either side, but Gough made no bones about the fact that the longer Maxse could keep the Germans occupied on his front while the other corps retired, the better it would be. He was glad to be able to tell him that the 20th Division was on its way to help him.

At XIX Corps Headquarters, at Le Catelet, near Péronne, General Watts’s situation was more serious. In principle his position between the valleys of the River Omignon and the River Cologne should have been more favourable, for it was billowing country of shallow valleys and low ridges well placed for defence. The distance between the two rivers was barely five and a half miles, and General Watts had two divisions to defend it. He also had a cavalry division in reserve. But the undulating ground from which, even in bad visibility, the Tommies might have repulsed a massed frontal attack was perfectly suited to an assault based on the Germans’ new tactic of speedy infiltration, and the mist clinging to the shallow depressions behind the British positions on the ridges had masked the fast-moving parties of enemy soldiers as they filtered through. The news that they had entered Templeux-le-Guérard from the north reached General Watts shortly after noon. It came as an unwelcome surprise, for this village was well inside the battle zone and the British line was a full mile ahead of it, on higher ground on the edge of Hargicourt village.

Between the two villages, the long, low valley where the River Cologne ran its leisurely course was pitted and scarred by a number of shallow quarries, many of them long and straggling where veins of chalk had been gouged haphazardly from the soil. The British Army, and in particular the Royal Engineers, had every reason to bless the local quarrymen who had unknowingly constructed such a splendid line of defence in the years before the war, for the use of an army which was not then in existence, in a war which had not yet begun. It had been a simple matter to link up the indentations and to convert this rough ground with its ready-made parapets and dugouts into a powerful redoubt, and indeed the main line of the battle zone had been sited round Hargicourt for this very reason. No one had conceived that the enemy would simply walk round it.1

When General Gough arrived at XIX Corps Headquarters the Corps Commander was obliged to inform him that his outpost line had gone, that his battle zone had been penetrated on his left flank, and also that, with the loss of Maissemy, his right flank too had been turned. So far as he could ascertain, his troops were fighting back, and they were fighting hard, but it was as clear to General Gough as it was to Watts himself that two weak divisions and some dismounted cavalry could not hold the Germans back indefinitely. Both men fully understood the seriousness of the position, and Gough did not feel obliged to adopt the same breezily cheerful attitude with which he had encouraged General Butler. He laid his cards on the table. He had earmarked the 50th Division to assist XIX Corps in case of need, but it was still at Guillaucourt, roughly twenty-five miles distant on the road to Amiens, and with the best will in the world it could not possibly reach the battlefront until morning. Neither man expressed the thought that, after a sleepless night culminating in a ten-mile march from the railhead, the men would hardly be at the peak of their performance when they did arrive. Still, the essence of the confused reports that reached Watts’s headquarters from the battlefield was that the centre of his front was holding, and Gough was able to cheer him with the reassuring news that XVIII Corps had formed a line south of Maissemy to cover his open right flank. He urged him to hold on to his existing front as long as possible, and to bend back his shaky left to join hands with VII Corps to the north.

General Gough did not have to impress on his Corps Commander the importance of ‘keeping in touch’. Even if the whole Fifth Army was obliged to fall back (and already he privately feared that it must), all would not be lost so long as the line remained intact as it retired. Now that the mist had dissipated, the advantage of well-sited positions had reverted to the defenders and, from the information he had – sparse though it was – General Watts was persuaded that his troops could keep the enemy at bay, at least until the arrival of the 50th Division.

As the crow flies, only four and a half miles separated Le Catelet from General Congreve’s VII Corps Headquarters at Templeux-la-Fosse, but the roads that meandered across country were little more than lanes, and Gough’s car was forced to travel almost twice as far, along the main road through Péronne. When he eventually hurried into Congreve’s office he was rewarded with better news. It would not be true to say that the General was in high spirits, but he was reasonably satisfied with his position. He was also vastly relieved, because, as he confessed to the Army Commander, only a few hours ago he had feared that his line had given way on the 16th (Irish) Division front. But the Irishmen had fought so doggedly and counter-attacked so brilliantly that assault after assault had been thrown back. It was true that his extreme right had been broken near the Cologne valley, where the flank of his neighbour General Watts had given way, but he had three divisions in the line and the 39th Division had been close by in reserve. Already, on his own initiative, he had ordered it up to fill the gap and to link up with the remnants of Watts’s XIX Corps on its right. Congreve was quietly confident that he could hold on, and Gough knew his old friend well enough to believe it. ‘Well done, Walter,’ he said. There was no need to say more. Time was pressing. It was now more than two hours since he had left General Butler’s headquarters at the southern limit of his army, and matters might have altered radically since then. A fresh batch of reports would be waiting at Army Headquarters. He half dreaded the news they might contain, but he took comfort in the fact that here, on the extreme left flank of the Fifth Army, VII Corps was standing fast.

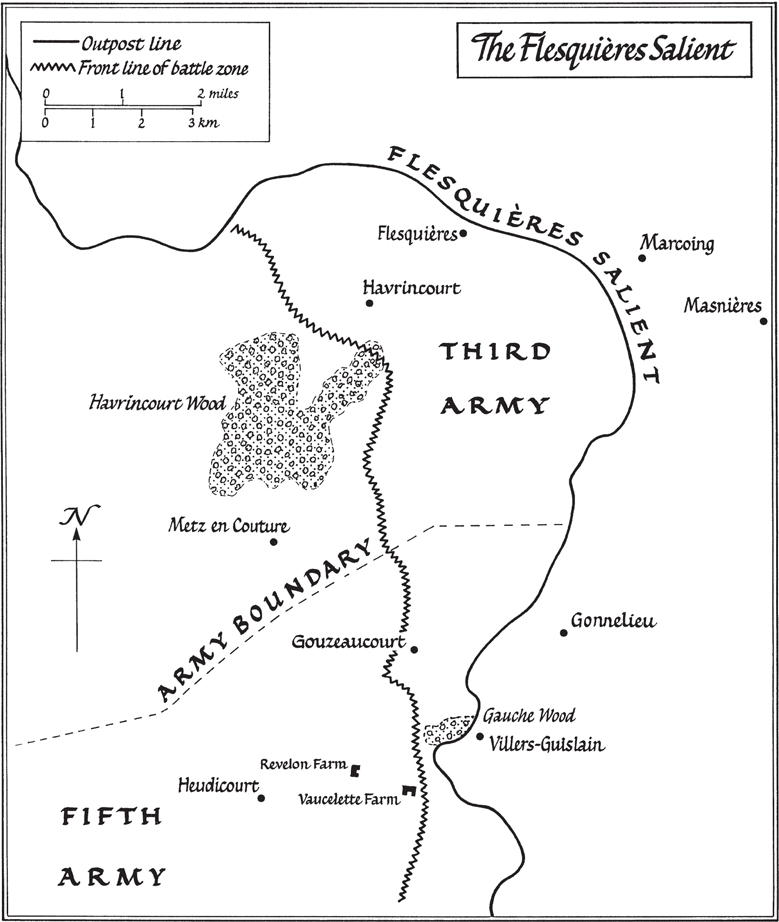

The 9th (Scottish) Division stood at the important juncture of the front where the left of the Fifth Army met the right of the Third, which continued the line to the north, and it was a position that was both vulnerable and dangerous. The boundary between the armies lay just north of Gouzeaucourt, and the outpost line east of that village dipped across the fields in front of the German-occupied villages of Gonnelieu and Villers-Guislain. The Scots had been in and out of this sector since February, and one sergeant whose task it was to allocate sentries to posts in the forward line never tired of a well-worn jibe addressed to the man on the extreme left. ‘There you are. Now if General Gough gives the order “The Fifth Army will right wheel”, you’ll be marking time for the rest of your life.’ The unfortunate Jock, realizing that he was the last man on the Fifth Army front, did not always appreciate this pleasantry.

It was an axiom of military doctrine that the junction of two armies was the weakest point of a defensive line, and a wily enemy would attack it if he could. This particular junction was more vulnerable than most, because it adjoined the Flesquières salient, which had been thrust deep into enemy territory in the Battle of Cambrai. Three divisions of the Third Army straggled round its rim, and, since it was the only ground which the Germans had not later won back, it was almost a point of honour to retain it.

It was not the enemy’s intention to mount a full-scale assault on the Flesquières salient, although the men who were holding it might have been forgiven for supposing otherwise. The bombardment had fallen on them just as heavily as it had on their right and their left, they had been soaked with mustard gas, and throughout the day their thinning ranks had thrown back a succession of violent attacks which had given every appearance of being the real thing. But they were not. They were a feint. It was the Germans’ intention to exhaust the British troops, to incapacitate them by means of gas and high explosive, and to pin the Tommies down until their own troops south and north of the salient had pushed westward. Then, converging on Havrincourt, they would pinch the salient out. But south of Gouzeaucourt, where the 9th (Scottish) Division stood at the hinge of the salient, the attack was intended to succeed, to punch a hole in the British defences, to swarm through it – and to keep on going.

At Gouzeaucourt on the extreme left of the 9th (Scottish) Division a company of the Highland Brigade was standing-to under the noses of the enemy in a line of scattered posts in front of Gonnelieu barely 500 yards distant on the slope ahead. A nervous sentry, acutely conscious that only a few hundred yards, a single sandbagged parapet and a narrow strip of barbed wire lay between him and the Kaiser’s Army, did not much relish being at the razor’s edge if the Kaiser were to launch an assault. But the Germans did not assault at Gouzeaucourt itself, and it was doubtful if they had ever intended to. More than once during the course of the morning, parties of enemy soldiers were seen approaching across the fields from Gonnelieu, but their progress was half-hearted, and the British guns had responded so speedily and fired so accurately that the Germans had soon turned tail. The posts remained intact.

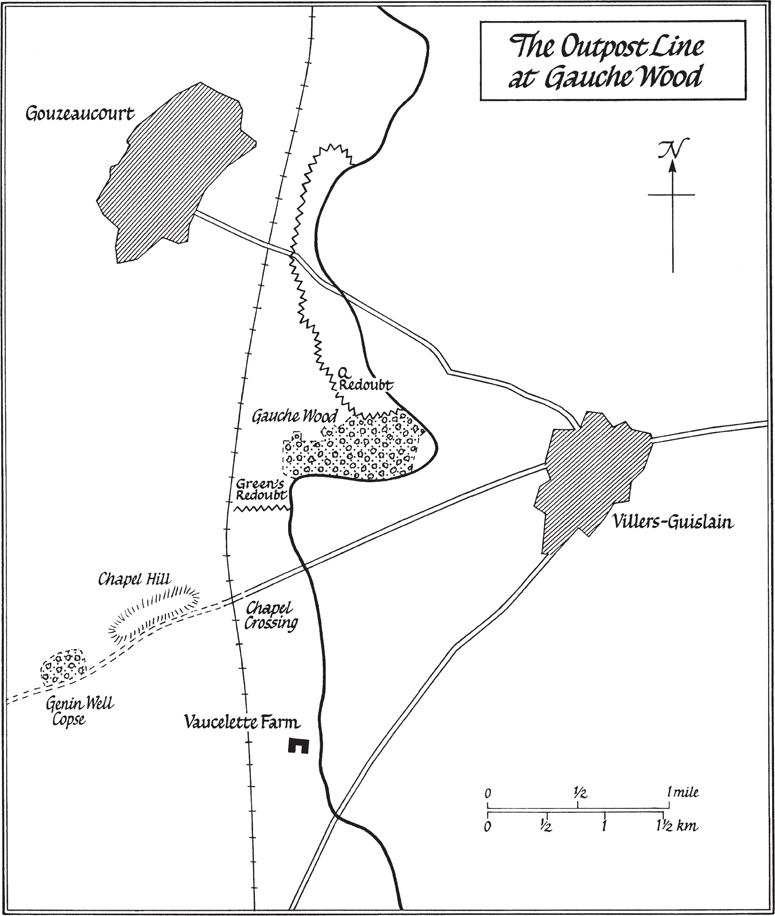

The full ferocity of the attack fell on their neighbours, a stone’s throw away on their right, where the outpost line ran down the hill along the forward edge of Gauche Wood. It was manned by B Company of the 1st South African Infantry, and Captain Garnet Green was in command.1

In May 1916 the South Africans had been sent to replace the 28th Brigade in the 9th (Scottish) Division. Most of them were not displeased, and some of them were positively delighted, for, although it was officially the 4th South African Infantry, one of the regiments which made up the Brigade was known more familiarly as ‘the South African Scottish’. They wore kilts of Atholl tartan, had a full-blown pipe band, and were referred to affectionately by the other battalions of the Brigade as ‘Our Jocks’. Their presence had mollified their new comrades, and somewhat reconciled them to the loss of the battalions of native Scots. Any lingering resentment had long ago been dispelled, for the South Africans had proved themselves to be ‘bonnie fechters’, and the homely vernacular compliment, never lightly bestowed, was no mean tribute to their prowess in the arts of war. In the eyes of the Division, no matter what their individual territorial allegiances might be (and they ranged from Natal via the Transvaal to the Cape), all the South Africans were accepted as honorary Scots, and some of the Lowlanders even assumed that the few Afrikaans-speaking soldiers in the South African Brigade were speaking Gaelic.

Like the Australians, every man in the South African contingent was a volunteer, and their sharpness of eye and their skill with a rifle – perfected in pursuit of small game on the farms and veldts of their native land – were legendary. Nor had they arrived as raw recruits, for the South African Brigade had come to the 9th Division straight from Egypt, and there, fighting in difficult desert terrain as part of a mixed force, they had put the Turks to flight at Agagia and occupied Barrani and Sollum. Some, like Captain Garnet Green, had fought in South-West Africa in the first year of the war.

Green had served as a hard-riding, sharp-shooting trooper of the 1st Royal Natal Carbineers, and he could out-ride and out-shoot any man in a brigade in which these skills were ten a penny. He liked to be where the action was, and when the South-West African campaign ended with the surrender of the Germans in July 1915 he had transferred to the South African force then preparing to leave for the war in Europe. One year later, and almost to the day, as a newly commissioned second lieutenant, Green led his men into Delville Wood in the Battle of the Somme. He was one of only two officers and 140 men who came out again.1 If any in the 9th Division had regarded the South Africans as cuckoos in the nest, they had changed their minds after Delville Wood.2

The line ran round its southern perimeter, facing the German line in front of Villers-Guislain. It was not much of a line, for there were only two posts just inside the wood, with another redoubt on the open ground near the south-western corner. The Springboks had two trench mortars and two machine-guns positioned to cover both arms of a part-sunken Y-shaped track that ran up the hill from Villers-Guislain, just a five-minute walk away for the woodcutters and occasional courting couples who had once used it. Paul Maze had sketched the position the day before from a vantage point south of the wood near Vaucelette Farm.

Although he was a Frenchman born and bred, Paul Maze had been part of the British Army since the first contingent of the Expeditionary Force had landed in his home town of Le Havre in August 1914. The French military authorities had declared him unfit for military service, but, armed with nothing more than a letter of introduction from the British consul at Le Havre, a gift for languages and a determination somehow to get into the war, he had sought out the colonel of the Royal Scots Greys and, in impeccable English, offered his services to the Regiment. It was all quite irregular, but the times were chaotic and the colonel, newly arrived, was struggling to arrange a thousand essential matters through official interpreters whose command of English was far inferior to that of Maze. So, with the encouragement of the colonel’s second-in-command, on whose plate most of the problems had landed, and the help of a friendly sergeant-major, who managed to produce various items of khaki kit which gave him some semblance of military appearance, Maze was co-opted into the regiment and set off for the war.

He had stuck with the Scots Greys through the retreat from Mons to the Marne, covering possibly twice the distance of any other man in the Regiment, sometimes on horseback, frequently by bicycle, carrying messages, liaising with scattered bodies of French troops, occasionally becoming hopelessly lost, and on one occasion narrowly escaping being shot as a spy. His services during the retreat had been invaluable. They soon became indispensable. Shortly after the Battle of the Marne, now respectably attired as a soldier of the French Army, he was officially attached to the staff of General Gough. Gough was then Commander of the First Corps, and when he was later appointed to the command of the Fifth Army Maze had remained on his staff.

In a sense, Maze was Gough’s window on the war, for Maze was an artist, and his meticulous drawings of the terrain, sketched in detail on the ground, were often of infinitely more use to the General than the flattened images photographed from aircraft a thousand feet above it. Furthermore, Maze could travel where the Army Commander could not, and he spent more time in the forefront of the line than at Fifth Army Headquarters. The officers of the official French liaison staff barely concealed their irritation at the presence of this upstart who so clearly enjoyed the confidence of the Army Commander, but Gough did not give a hoot. In his view Maze was worth a dozen mere interpreters, and he valued him not just for his artistic skill but for his artist’s eye. Maze was an acute observer, and the reports he brought back of what he had seen and heard, the information he gleaned on his travels, were of considerable importance. Maze had a roving commission, and Gough personally saw to it that he had the entrée to every corps and divisional headquarters on his front and in his army.

Travelling fast on a powerful motorcycle, Maze could negotiate congested roads and reach the front even at the height of battle. No one questioned his right to go where he liked, and his laissez-passer bore not only the official stamp of every corps and divisional headquarters in the Fifth Army, but the signatures of its highest-ranking officers. Although officially he held the honorary rank of sergeant, not the least of this paragon’s attributes were his charm and ease of manner, which made him just as welcome in a mess presided over by a brigadier as it did in a front-line post in the charge of a corporal. The General was equally interested in Maze’s impression of both, particularly on the matter of morale.

Sometimes, as he sketched the tortured landscape of his native France, Paul Maze’s impressions were more personal and more painful. Looking across the ruins of St Quentin, remembering the pastels of Maurice de Latour which had hung in the museum, he was saddened to think that they too might be lying among the wreckage and the debris of the town. He had felt much the same sadness on the slopes of Chapel Hill on the eve of the German push. In the battle zone across the ravaged farmland, he could see the skeletal roofs of ruined Gouzeaucourt and the trench that straggled down to protect the flank of the 9th Division. Off to his right all was quiet at Gauche Wood. It was late in the afternoon and, being careful not to expose himself to the eyes of the enemy, Maze made his way down to the post they still called Vaucelette Farm. Any resemblance to a farm had vanished long ago, but he found the battalion headquarters of the Northumberland Fusiliers in a deep dugout nearby and stopped there to beg a cup of tea. He found almost a party-like atmosphere, for there was a wind-up gramophone and a selection of popular records, the officers were youthful, and their unspoken attitude seemed to be that, since there was nothing to do but wait, they might as well be cheerful while they could. It might have been a sixth-form beanfeast. No one mentioned the coming attack.

Maze produced his sketchpad and, by the light of a hurricane lamp, made lightning sketches of the young officers round the table. The Colonel was an older man, and Maze could sense the anxiety beneath his carefree manner. A little later, when dusk fell and it was safe for Maze to retrace his steps to the place where he had left his motorcycle, the Colonel went up the long stairway to the dugout entrance, shining his torch to light the way. Outside it was eerily quiet, with a hint of the mist that would shortly begin to gather. Across the valley to the north Gauche Wood was a barely discernible smudge on the hillside, but, although the land was sinking into the dark, Maze could see it clearly in his mind’s eye, for he had sketched every cleft and gully. Now that they were alone, Colonel Howlett spoke of the attack. It might be tonight, he thought, or might be tomorrow, but whenever it came they would be ready. He seemed to have something else on his mind and, as Maze shook hands and wished him luck, he said hesitantly, as if by an afterthought, ‘You know that sketch you did of me just now in the dugout? I wonder if you would send it to my sister?’ Turning his back on the line to mask his flashlight, he scribbled the address on a piece of paper. As he tucked it carefully into his top pocket, Maze wondered if Howlett had had some kind of premonition.1

When the assault was launched on the 9th Division front, the full force of the attack fell on Gauche Wood. The storm troops swarmed towards the hill, and a heavy smokescreen mingling with the mist as they approached hid them from even the most vigilant of lookouts. They came with rifles slung and stick bombs at the ready; they came for once in silence; and they seemed to come from everywhere, flinging themselves en masse at the eastern fringe of Gauche Wood, plunging along its southern edge towards Garnet Green’s redoubt.

Machine-guns firing blindly into the mist traversed the front by instinct and by guesswork, but the enemy soldiers were upon them, and even behind them, almost before they knew it. Filtering along the very dips and gullies Paul Maze had so assiduously plotted in his sketches, they had slipped between the outposts to take them from the rear. Two of the posts were overwhelmed straight away. Leaving the moppers-up to deal with the remnants, flinging bombs, and fighting hand to hand, the German soldiers began to carve a path through the wood. Second Lieutenant Meller Beviss had barely half his platoon left, but they fought like furies, and yard by yard they battled their way through the wood to the open ground behind. And when the Germans halted among the battered trees to gather their scattered force, they began to dig, and they dug like men possessed. It was only a brief respite, but it was long enough to establish a feeble line only fifty yards from the edge of the wood. Glancing to his right, Beviss could see that Green’s redoubt had gone and that Green and the survivors of his command were fighting their way back to join them.

By the time they got there the enemy was preparing to assault, and there were fewer than fifty men with rifles plus a single Lewis-gun to meet them when they came charging from the wood. The Germans charged in full-throated cry and they flung themselves forward in long lines, three deep. And they charged with infinite courage, without the support of artillery or machine-guns. The distance was so small, the outcome seemed so sure. But they were at point-blank range, and now that the smoke had dispersed and the fog was lifting, now that, at long last, there was a visible target, the dazzling marksmanship of the South Africans came into its own. It stopped the Germans in their tracks. The assault ground to a halt, and, when the lines wavered and the enemy soldiers tried to dig in on the edge of the wood, the bullets spitting from the Springbok rifles caused such mayhem that they soon retired into the wood for shelter. It was eleven o’clock in the morning, and the fight for Gauche Wood had gone on for more than two hours. For half an hour longer the Springboks kept the Germans at bay and then, to their exquisite relief, the guns, which had been firing on the SOS line in No Man’s Land on the far side of Gauche Wood, shortened range and began to pound the wood itself. Some desperate runner had got through with the message that Gauche Wood had been lost – and he had made it not a moment too soon.

At 9th Division Headquarters disturbing messages had been coming in all morning, and General Tudor was in a quandary. No attack had yet developed on the front held by the Highland Brigade at Gouzeaucourt and, thanks to the stand of the South Africans in the outpost line, the front line of his battle zone was safe. The flank, however, was not. News of the 21st Division on his right was confused and contradictory, but by midday it seemed certain that the strongpoint at Vaucelette Farm had gone. The trenches behind it were still holding out, but a visual report from a divisional observer suggested that the 21st Division had withdrawn its troops from Chapel Hill. That was a serious matter. It was also a matter of some annoyance to the Divisional Commander. This area had previously been within the sector of the 9th Division, but ten days ago, when his troops had returned to the line after a much-needed rest, General Tudor found to his consternation that these vital positions had passed out of his control and been reallocated to the neighbouring division. His Brigade Commanders were equally dismayed, for Chapel Hill, lying immediately south of their battle zone, was the bastion on which they had depended to protect the Division’s right flank.

It was not much of a bastion, and not much of a hill – it was a long, low knoll, a mere streak on the landscape south of Revelon Farm. But now that it had been lost General Tudor hardly needed to inform his Brigadiers that steps must immediately be taken to recapture it. The 1st South African Regiment holding the battle zone was to swing round to face south and to stand fast along the divisional boundary. The Jocks of the South African Scottish would advance to retake Chapel Hill, while the ‘details’ who had been left behind near Heudicourt, and the Jocks of the Lowland Brigade in reserve, were ordered forward to the third line of the battle zone to support them.

The Lowland Brigade, clustered round the village of Heudicourt, had been on the point of moving forward to relieve the South Africans in the front line, and all that could be found for A Company of the 11th Royal Scots by way of billets were some tattered camouflaged tents among the ruins. Until the bombardment started, and despite the cold, the damp and the discomfort, Alex Jamieson had considered that he was in luck. Their tents were near the gun-line, and in a dugout in the ruins close by he had had the good fortune to find an artillery canteen whose existence was known only to the gunners. What was more, Alex had money in his pocket, the canteen had just received a small supply of chocolate, and although, strictly speaking, the canteen had been set up for the benefit of the gun-crews, the corporal in charge magnanimously allowed him to buy some, if only a single bar. To a sweet-toothed boy of eighteen it was manna from heaven, and Alex set off to find a quiet corner where he could enjoy his booty. As he was about to pocket his change, it struck him that he had been given too much.

42821 Private Alex Jamieson, MM, 11th Bn., The Royal Scots (Lothian Regt.), 9th (Scottish) Division

I went back into the canteen and said to the fellow at the counter, ‘You’ve given me too much change.’ He looked at me as if I should have been in the Salvation Army instead of the British Army! He said, ‘My God, Jock, you’re an honest man!’ And he gave me another bar of chocolate and wouldn’t take the money for it, so I was well pleased, because he was only allowing one bar per man, so it had paid me to be honest. If I’d kept the extra money (it was only a few centimes) I wouldn’t have been so well off, because I got two bars for the price of one. But it didn’t enter my head to keep it. It’s not that I was a goody-goody or anything like that: I just knew that it wasn’t the right way of doing things.

It took more than a few months in the Army and four weeks at the front to bend the principles of a Glasgow Boy Scout.

The canteen had long ago shut up shop, and its stock had almost certainly been blown out of existence by the bombardment that had reduced the ruins of Heudicourt to rubble. When the shells began to fall, Jamieson’s company was led into a small valley to shelter in the lee of an embankment. As the day wore on and the situation worsened, they moved forward into the Heudicourt valley.

Private Alex Jamieson, MM

We were right out on the open, and we were told to lie down on some slightly raised ground and to make some sort of protection by digging in with our entrenching tools. Well, an entrenching tool is a completely useless piece of equipment unless it was meant to protect the base of your spine when it was hanging from your belt, but it only added to the weight we had to carry when we were on the move. The small pile of earth I managed to throw up was absolutely laughable!

While we were there some men of the Lincolns of the 21st Division started coming back through us – not in great numbers, just in ones or twos, because the 21st had had a very bad time in the front line and they were getting out of it as quickly as they could, but they were stopped by our officers and told to join us. They weren’t reluctant, they were quite happy to stay, but it was just that they hadn’t known what to do. So we lay there for a bit, and after a while we had to move forward across a sunken road and some distance ahead there was another ridge, and we hadn’t been there long when we saw the Germans coming over it. They were absolutely pouring over it, just like a crowd coming out of a football match. They were packed together coming over this ridge, and we were ordered to open fire. They must have been near enough half a mile away. I know I had my sights at the highest they would go, they were so far away. But these bullets must have been landing in amongst them even at that distance, and they just melted away! It was the first time I’d fired a rifle in anger, so to speak.

We started advancing towards that ridge and we had to cross a sunken road, and as we ran forward to occupy a rise a German machine-gun opened up and Bill Relph, who was just on my right, was hit and he fell down. Naturally I stopped to help him, but the corporal bawled at me to leave him alone and carry on. Well, it’s instinct to help a pal, isn’t it? But I just had to carry on. Poor old Relph wasn’t more than two or three feet away from me, but I had to leave him there. When we got up on to the ridge the corporal dropped down beside me and he told me that Relph had gone west.

They were clinging to the fringe of Chapel Hill, but even with the help of part of the 2nd South African Infantry, which had swivelled round to stand along the flank between them and Gauche Wood, they could get no further. It was the South African Scottish who managed it. They were only a company strong, but there was no stopping them. They swept through the line and on to the knoll, chased the Germans from the crest, and dashed on to clear them from the captured trenches on the further slope. And there they stayed, stretching hands to join up with the ragged line on their right. By seven o’clock, to the vast relief of General Tudor, and despite the perilous gap in the line beyond it, the flank of the 9th Division had been made safe.

Later, when darkness fell, and the last of the reserves moved forward, the weary boys of Jamieson’s battalion were moved back for the night to rest in whatever shelter they could find in the redoubt at Revelon Farm. Towards midnight, when enemy patrols crept cautiously out of Gauche Wood there was no one to oppose them. The Springboks had fought to the last, and the bodies of the dead lay slowly stiffening where they had fallen. Garnet Green was there. Second Lieutenant Meller Beviss and a mere handful of survivors had managed to crawl back.1

But the battle zone had not been breached, the Germans had been kept at bay, and at the end of the long day’s struggle only the outpost line at Gauche Wood had passed into the hands of the enemy. The 9th Division had fought hard to hold their ground, and the weary remnants knew that they had done well.