Illustrations

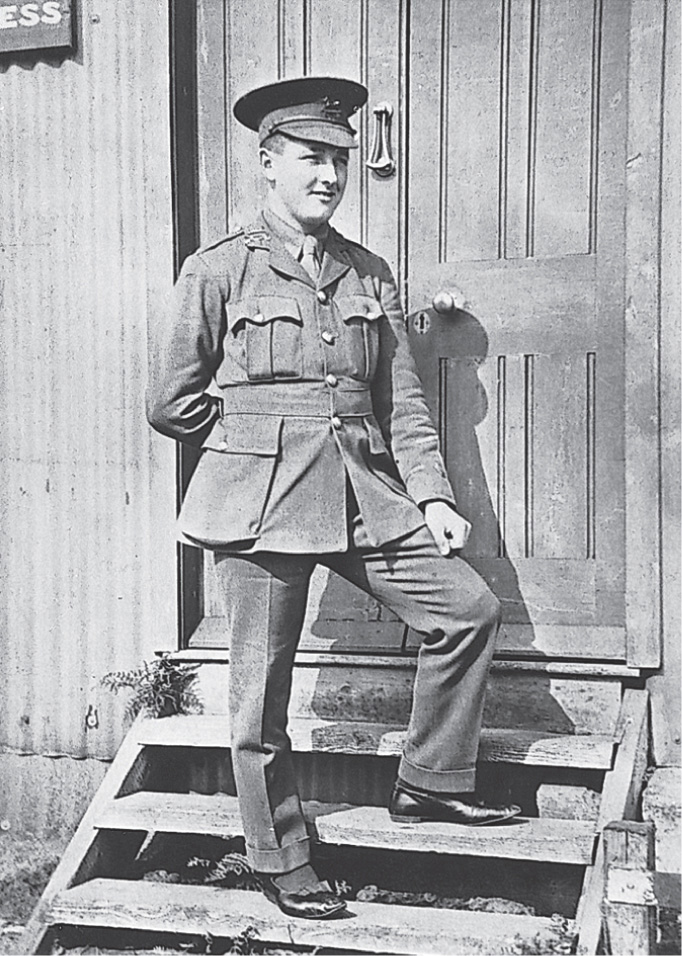

1. Private Alex Jamieson, 11th Royal Scots, (right) photographed with a friend. Within weeks of his arrival in France he was in the forefront of the fighting. ‘That was the first moment that I was frightened, really frightened, because the orders came along, “This position must be held at all costs until the last man.” ’

2. Reinhold Spengler as an infantryman of the 2nd Company, 1st Bavarian Infantry Regiment, in February 1917 (Photo: Richard A. Baumgartner).

3. Reinhold Spengler as a newly commissioned officer in 1918 (Photo: Richard A. Baumgartner).

4. Traces of the Hindenburg Line still scar the ground near Urvillers. From this spot, or very close to it, Leutnant Reinhold Spengler led his platoon to the assault.

5. The remains of the mighty Hindenburg Line along the Oise Canal near Vendeuil and Moÿ.

6. The defensive posts of the Hindenburg Line ran all along the eastern bank of the Oise Canal, and the trenches behind them can still be distinguished on the ground.

7. The formidable concrete shelters were impervious to shell-fire.

8. Looking north from Ly-Fontaine towards Benay. The clump of trees in the middle distance is roughly where the last gun of C83 Battery kept firing to the last and Gunner Charlie Stone won the VC. The Germans were advancing across the open country on the right.

9. ‘Our infantry stormed on towards a railway embankment, driving the English in front … We were lying on one side of the embankment, the English on the other … our ammunition was dwindling down to almost nothing …’ Georg Maier, 1st Bavarian Division. ‘When we saw the enemy retreating, we put our machine-guns on the top of the embankment and fired at them streaming across a large field between Flavy-le-Martel and Faillouel’ Leutnant Reinhold Spengler.

10. The chateau at Rouez village where the 10th Essex were surprised by the pursuing enemy, photographed on another misty morning eighty years later.

11. The 10th Essex at Rouez and the keeper’s cottage in an artist’s impression. ‘There was a gamekeeper’s cottage right on the edge of the wood, and the Huns had a machine-gun at every window …’ Captain R. Chell.

12. A modern view of the same spot.

13. The keeper’s cottage today. On the walls, memorial plaques commemorate the French regiment who arrived to help the 10th Essex hold up the enemy advance on 23 March 1918.

14. The graves of German soldiers killed in the fight at Rouez. They lie in a cemetery just beyond the keeper’s cottage, on the site of the line the Essex took up when they rushed to the attack from the wood in the background.

15. Gauche Wood, where the South Africans made their gallant stand in the outpost line south of Gouzeaucourt. Captain Garnet Green’s redoubt was roughly on the site of the field which is white-sheeted to protect early crops.

16. Men of the Royal Naval Division still lie just behind the old front line at Villers-Plouich, just north of Gouzeaucourt in the Flesquières salient. On modern French ordnance maps the ground is still marked ‘Champs de Bataille’.

17. When Second Lieutenant Peter Wilson, MC, was transferred from the West Yorkshire Regiment he had the impression that the wild parties of the Royal Flying Corps were almost as dangerous as war in the trenches or in the air.

18. Second Lieutenant Gerard Robin, RFC, snapped on his arrival at 41 Squadron. Within days he narrowly escaped death when his burning aircraft went into a spin. ‘Of course I had terrible wind up … I was at 13,000 feet when I began this stunt and at 5,000 feet when I pulled her out.’

19. The temporary bridge at Masnières erected by the Germans above the wreck of the original bridge, collapsed under the weight of a tank. Frank Caulton scrambled with difficulty across the shattered girders in November 1917 and was subsequently captured.

20. The sunken road south of the village of Beaumetz where Second Lieutenant Dick Gammell’s Brigade signals HQ was burrowed into the high bank beyond the tall tree. The HQ of Major Ronald Ward’s 293 Artillery Brigade was close by, and when modern hedging machines have peeled back the undergrowth the traces of the entrances to these and many other dugouts are still discernible.

21. Major Ronald Ward of C293 Battery, who rescued his guns from beneath the noses of the Germans advancing at Doignies.

22. Major Ronald Ward, C293 Battery, caricatured by an artist comrade.

23. Looking towards Doignies from the sunken road at Beaumetz across the fields where the guns of C293 Battery were disposed – and later rescued by Major Ward.

24. The forward gun of C293 Battery was situated in this field on the edge of Doignies. Cows now graze in the rough pasture, still pock-marked with traces of the fighting.

25. The redoubts that formed the front line of the British battle zone round Hargicourt village are still evident on the chalky soil.

26. The entrenchments in the old quarries at Templeux-le-Guérard, where two companies of the 7th Lancashire Fusiliers and two of the Border Regiment held out until they were surrounded.

27. The temptation of abandoned British supply dumps to the badly fed German soldiers significantly slowed the progress of their advance. ‘Unimaginable treasures were found inside, but we could only pick up a few things to carry along – bacon, ham, corned beef, chocolate, cigarettes and real tobacco. (Our own smokes were terrible!)’ Leutnant Reinhold Spengler. (Photo: Imperial War Museum).

28. Brigade-Major Harold Howitt, MC, leaving Buckingham Palace with his wife, Dorothy, after receiving his Military Cross from the King.

29. The village of Lechelle, where Battalion Headquarters, 23rd Londons, was overrun.

30. Battalion HQ at Lechelle was in the farm at the top of the road. ‘I was belting up that road as hard as I could. I hadn’t gone more than thirty, forty yards before four Germans stepped out in front of me, all with their rifles trained on my stomach, and that was the end of my fighting!’ Captain George Brett, MC.

31. Lieutenant L. Chamberlen, MC, 2nd Rifle Brigade, who was wounded at Pargny on the River Somme. ‘… we could see the Hun coming down the hill on their side while we ran down the hill on ours. We went like hell!’

32. Leutnant Fritz Nagel, whose anti-aircraft gun-crew K Flak 82 was roped in to help the German infantry attacking from Albert on 27 March 1918 (Photo: Richard A. Baumgartner).

33. To prevent injury from flying glass during air raids and bombardments, windows throughout Paris were reinforced by a network of gummed-paper strips in designs which were often elaborate in smart premises like these.

34. The operation of the long-range ‘Paris Gun’, which bombarded the French capital from a distance of seventy-five miles.

35. Private Horace Haynes, 2/6th Royal Warwicks, (left) with another of the young soldiers who were rushed to the front. ‘When we went on parade, instead of saying “13 Platoon, Attention!”, our platoon officer said “56 Draft, Attention!” ’

36. Capitaine Désiré Wavrin, 62nd [French] Division. ‘I honestly believed that my last hour had come when the enemy brought up their awful Flammenwerfers and hosed us with liquid fire. The flames were less than a metre from my face. I wondered if I was going to be grilled like a piece of pork!’

37. The fast-firing French gun the ‘Soixante-quinze’, the most famous artillery-piece of the French Army, was prized for its performance.

38. The elaborate sculptured façade of Mailly-Maillet church was protected from shell-fire by wattle screens. It was used by the New Zealanders as a dressing station. ‘I’m lying there … looking at a wall of bricks forty or fifty feet high … Of all the bloody places to put a wounded man! One smack from a shell and tons of them would be down on us’ Private George McKay, NZ Rifle Brigade.

39. A modern view of Mailly-Maillet church. Although the village was in ruins by the end of 1918, the fine façade of the church escaped destruction.

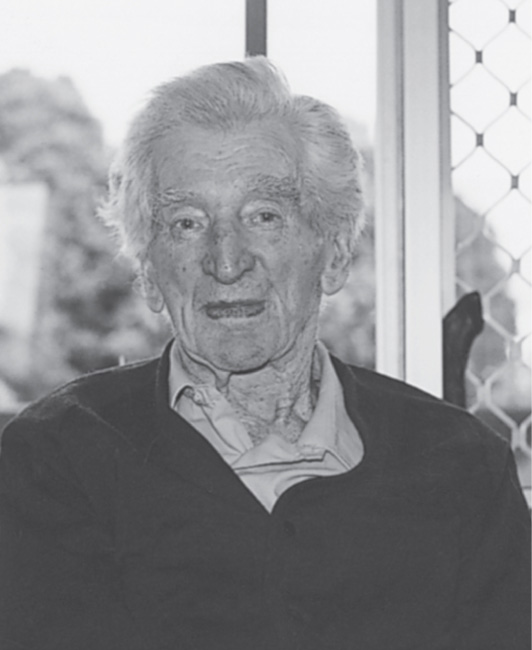

40. Private George McKay safe in hospital after being wounded in March 1918

41. At home in New Zealand more than seventy-five years later.

42. New Zealand soldiers posing for an official photograph in a respite from the battle.

43. Probably the humour of the postcards soldiers sent home was not always appreciated by their anxious families.

44. French women, evacuated far from their homes, supported themselves by manufacturing silk postcards and creating the kind of patriotic dolls reproduced on this postcard.

45 and 46. Such postcards were sent to wounded soldiers’ relatives, who could be given free or cheap railway passes to visit the injured. There were also free travel facilities if a badly wounded soldier was in hospital in France.

47. Lieutenant Jim Aldous, MC, (right), with Captain West, MC, at rest after the touch-and-go fight at Adinfer Wood.

48. The chateau of Grivesnes, sketched on 13 April, two weeks after the epic fight to defend it.

49. The chateau of Grivesnes, restored after the war, but now derelict and abandoned.

50. In the aftermath of the fight on 31 March, dead German soldiers lie in the chateau park at Grivesnes, beneath a notice which ironically reads, ‘It is expressly forbidden for troops to enter this property.’

51. A poilu of the 350th Régiment d’Infanterie sketched two weeks after the first German assault, on guard at a barricaded window in the chateau of Grivesnes.

52. Lieutenant-Colonel Lagarde with survivors of the 350th Régiment d’Infanterie who defended Grivesnes.

53. Plaques on the wall outside the chateau commemorate both French and German regiments which fought here between March and August 1918, when Grivesnes was in the forefront of the line.

54. British veterans welcomed by Monsieur Claude Dubois, mayor of Grivesnes, in July 1996.

55. Lance-Bombardier Robert Ford. ‘I wanted to be a signaller in the Royal Engineers, but they wouldn’t have me because I wore glasses. So I joined the Royal Artillery. They didn’t care. You said you were nineteen and that was good enough for them.’

56. Major Harrison Johnston, in command of the 15th Cheshires. ‘The general met me and told me to line the road from the junction to the river – a frontage of about 1,000 yards. Ye gods, I had about 150 men then!’

57. Although many guns were lost in the early stages of the retreat the gunners continued to give sterling service very close behind the allied lines. Again and again guns like these 18-pounders thwarted the enemy’s attempts to storm forward.

58. Private Stanley Sutcliffe, 51st Battalion, AIF, who helped to thwart Ludendorff’s final bid for Amiens. ‘It seemed a strange thing that we should be fighting on the very same hill on which a year before we used to practise attacks in making ready for Bullecourt.’

59. Seventy-five years after he was taken prisoner, Private Walter Hare was welcomed by the owners of the farm close to where he was captured. ‘… the Germans got a machine-gun into a farmhouse on the left and they were shooting down the road at us. It was murder!’

60. The letter written by Brigade-Major Harold Howitt to his wife during a respite from the Battle of Amiens.