Piper’s Secret

Most people will think Piper’s secret is rather small, but the white guy who dated her and took her to his prom wasn’t the only one. And Piper’s mom doesn’t know about any of the others, even though mother and daughter have always talked about everything. Piper’s secret with white boys involves not dating but being accosted by invasive, entitled, and leering white boys who were emboldened by whatever fantasies of blackness they imbibed in the 1980s.

This story almost didn’t make it into Piper’s chapter on A Mercy. In the first drafts, Piper kept her distance from this painful past, instead taking a scholarly approach to exploring Morrison’s novel, especially the mother-daughter relationship at the heart of the story. Florens’s mother sacrifices everything to protect her child from a predatory slave owner, and Piper wrote beautifully about the scene of motherly sacrifice without saying one word about herself. She described Morrison’s depiction of a lascivious white man who tries to buy Florens, a mere child, but she had not really mined her own experience to make this violation relevant.

While we were discussing that scene of the mother’s sacrifice the way any book club might discuss a scene, Cassandra—who knew Piper for years—suddenly asked about her teenage years in Connecticut.

Piper looked confused.

“What about that white boy in high school?” Cassandra asked. “You should write about that.” (Cassandra used the word “that” and not “him,” revealing her curiosity about what had happened.)

Piper looked to the rest of us for help. We were workshopping each other’s drafts, and Piper—not receiving any help—smiled in a noncommittal way, shook her head at the ceiling as if she really wanted to say, “Damn it, Cassandra, shut up!”

We shifted our eyes from Cassandra to Piper and back again. The two friends were slipping into something private, something we were outside of. After all, Piper and Cassandra had a shared history: four years together at Spelman College, where they were both students; much later they would both become professors (through the luck of the draw) at the same institution; and more recently they had bonded as new mothers, holding each other’s babies, and then later giving each other advice as their children grew rapidly before their eyes. And yet these two professional women could not possibly have been more different in background and temperament.

When Cassandra first read Piper’s draft about her childhood (absent of any mention of white boys), she could not even make sense of Piper’s earliest memory of being called the N-word.

“How can you possibly pinpoint a first time?” Cassandra asked.

Silence. Furrowed eyebrows.

“I mean how can you possibly remember a first time?” Cassandra persisted. It made no sense to her because in the Alabama of her childhood that hateful word was so commonplace she couldn’t have separated any single moment from the many others.

“Well, come on, come on,” Cassandra said. “Tell us what happened in high school. That’s more interesting than some white kid on the playground trying to feel big by calling you names.”

We had, in fact, already workshopped Piper’s story of her early childhood, but this second draft still had not yet included anything about the way she had been treated.

“You can’t write a whole explanation of what it’s like to grow up the only black kid in your school and then stop before the problems really started. You’ve got to talk about that white boy!” Cassandra insisted. “You know it’s true.”

Piper looked away and hummed.

“I can’t put that in my chapter because . . .” She stopped. “Because my mom’s going to read this book.”

Piper’s mother, in fact, had already read an early draft, a draft without the leering and invasive white boys.

Not pulling back, Cassandra started again. “Piper, really? You are a fortysomething, grown-up woman with a husband, three kids, and the best mother in the world. You’ve got to write about those boys.”

“Slow down,” Winnie said. “Boys? As in plural?”

“Uh-huh.” Cassandra nodded. “There it is.”

Then Piper let it all out, telling us about the one guy Cassandra had already heard about, a second who leered at her like he was entitled to her, and a third who never got named, and they seemed to pop up like zombie placards in a cheap haunted house. But instead of zombies, they were real boys and men, still walking the earth.

With complete innocence, Juda threw up his hands and said there were “just too many white guys.” What he meant was that he could not keep them all straight in his head, but the idea of there being too many white guys seemed ambiguous and so that phrase dogged Piper for the rest of our project.

“Yes, too many white guys indeed.” Cassandra cackled. “That’s got to be the title of your chapter.” But having a title didn’t make it any easier to write.

And it was one of the hardest-written chapters in the collection, with each of us sending Piper on different journeys into early and painful memories of being the only black kid in a sea of white Richards and pale Susans, navigating friendships and the aggressions of teenage boys.

As our manuscript was nearing completion, Piper announced to the group that her mother was coming to visit. She paused for effect. “Well, I still have not yet told her about that white guy (or guys) in high school.” She seemed seriously concerned about it, but Piper has the kind of smile that endears everyone to her, and the smile, in that instant, modulated into one of the most inscrutable expressions. Each of us wondered, “Was she really worried?” But then she sent out a quick burst of laughter that said no, she would talk to her mother and it would be healing.

“Well, I guess I better tell her,” she said, “before the book comes out.”

“Yes,” we shouted. And then she echoed our “yes” with a childlike voice, maybe a little nervously, knowing we weren’t the ones who would have to face our mothers—close or not—with a secret that had grown over the years.

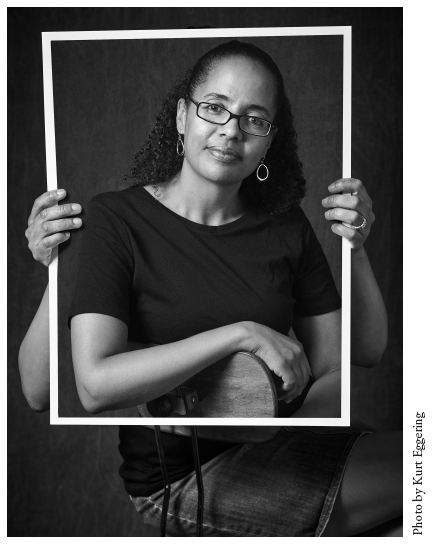

If you are wondering how the conversation went, we do too. We are writing this final addition to the book on the eve of Piper’s mother’s visit. If we were to imagine that meeting, we would first place Piper in a seated position close to her mother, her hands clasped as in prayer, not because this needed praying over but because this is how she would carry small secrets to her best friend. Piper’s mother sits across from her, her youthful sparkle making her look more like a sister than a mother. She too would have her hands clasped in prayer, not because a mother’s prayers were needed but because she would be anticipating everything—the secrets, the hurt, and the shame—and she would wish to lift some of that hurt from her daughter’s hands.