IT HAS BEEN noted by many observers of Paris that the city is essentially a collection of villages. The five quartiers featured here—in the third, sixth, twelfth, thirteenth, and seventeenth arrondissements—have still retained their neighborhood feel, and a visit to any one of them will reveal dimensions of Paris well beyond its more famous grands boulevards, rues, and places.

CATHARINE REYNOLDS, introduced previously, was a contributing editor at Gourmet, where this piece originally appeared in 2001.

YOU’VE PROBABLY CLIMBED the Eiffel Tower and checked out the stained glass at the Sainte-Chapelle. But have you really seen Paris? Beyond its set-piece monuments and cultural icons, the Paris of Parisians is a collage of villages. And visitors who venture outside the Eiffel–Concorde–Notre-Dame triangle to explore these enclaves will discover another dimension of the city.

YOU’VE PROBABLY CLIMBED the Eiffel Tower and checked out the stained glass at the Sainte-Chapelle. But have you really seen Paris? Beyond its set-piece monuments and cultural icons, the Paris of Parisians is a collage of villages. And visitors who venture outside the Eiffel–Concorde–Notre-Dame triangle to explore these enclaves will discover another dimension of the city.

It’s something of a miracle that so many distinct neighborhoods survive. And it’s Baron Haussmann, often condemned for the uniformity he imposed on Paris and for the broad boulevards he cut through medieval areas in the mid-nineteenth century, who may, ironically, be indirectly responsible. Today, the boulevards carry the worst of the city’s traffic, leaving the byways to the locals. Nor can you discount the role of what might be called the tyranny of the baguette. This staple goes stale quickly, making daily provisioning essential and thus encouraging the survival of local food shops along with the street life they promote.

The five quartiers featured here, many of them recent additions to Parisians’ “hot” list, have all retained that neighborhood feel. They are as varied as their inhabitants—and seem to us perfect examples of what makes the city one of the world’s liveliest and most livable.

In spite of its location in this central arrondissement, Temple, a tangled skein of streets north of the Picasso Museum and south of the Place de la République, has been largely overlooked in the dramatic gentrification that has renewed the Marais over the past thirty years.

At least until recently. The narrow streets—many of them named after the provinces of France—are still lined with handsome seventeenth- and eighteenth-century hôtels particuliers, not all of which have been restored. The generous spaces and sleepy, very Parisian aura here have attracted artists, young professionals, in-the-know foreigners, and a burgeoning gay community. Most of these new arrivals come armed with more panache than cash, and today they share the sidewalks with the artisans who have long sustained the area.

The quartier remains identified with a building that is no longer there: the Temple, a priory whose name derived from that of the Knights Templars, a military and religious order founded during the First Crusade. The organization once controlled a walled city covering much of both the third and fourth arrondissements. Midway through the Revolution, the Temple became a prison, and en route to the guillotine, Louis XVI and his family were some of its first inmates. In an effort to erase memories of the pitiful child king, Louis XVII, who died there, Napoléon demolished the tower where the family had been held.

Today, this peaceful area is one of the most forward-looking in Paris. The young lovers who wheel their firstborn around the duck pond in the Square du Temple are likely as not dues-paid members of the Net set who flock to the ultracool Web Bar to surf and salsa. This neighborhood invites the pedestrian: the one-way system discourages through traffic, so you can zigzag back and forth, here admiring an ivy-hung courtyard, there sizing up a produce display. Shops and galleries are gradually displacing the ateliers of wholesale jewelers, who have populated the quartier for centuries, but the newcomers are somehow more low-key than those who have taken over the streets adjacent to the Place des Vosges.

Perhaps this is because the Temple remains a vibrant residential neighborhood. Afternoons see youngsters, testing the limits of their trottinettes (scooters)—and of their parents’ patience—just avoiding collision with dealers shuttling fifties furniture into their boutiques and graphic artists piloting portfolios into taxis. And households supply their tables along the rue de Bretagne, where butchers, fishmongers, and greengrocers compete with merchants in the newly restored Marché des Enfants Rouges, the capital’s oldest market.

In the Parisian lexicon, stressé is the all-purpose adjective. And for many young urban professionals, the human scale of neighborhood life in the villagy quartiers on the city’s periphery is the sovereign antidote. Originally hamlets in their own right that were annexed wholesale to Paris on January 1, 1860, these enclaves come by their bucolic manners honestly.

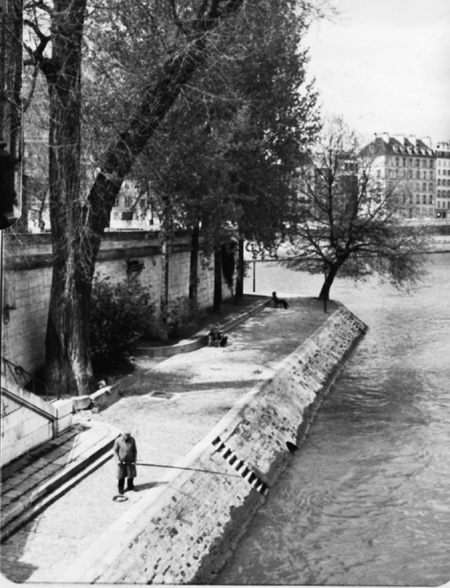

Just a few short years ago, an address aux Cailles, as the Butte-aux-Cailles is lovingly called, would have taken some explaining. These days, however, it excites raw envy, as more and more people discover this pocket of intimacy deep in the western section of the thirteenth, only a short Métro ride from the humming heart of the city. Butte means “knoll,” and in Paris is more commonly applied to the Butte Montmartre. The Butte-aux-Cailles has Montmartre’s charm, but, being less publicized, it is less visited. And its residents are determined to keep it that way, trumpeting that the Cailles has no attractions—perhaps forgetting that this is precisely what explains its appeal. This forgotten part of Paris, with its cobbled streets and old-fashioned streetlamps, exudes a provincial atmosphere of permanence.

The Butte-aux-Cailles earned a place in history in 1783, when the world’s first hot-air balloon landed there after a twenty-five-minute journey from the western side of the city. The area remained sparsely populated until the middle of the nineteenth century, when the poorest of Parisians, dispossessed by Baron Haussmann’s slum clearances, took refuge there. Ragpickers soon joined them, but infrastructure was slow in coming.

Today, the area tempts you to wander aimlessly: to discover a litter of kittens snoozing on a windowsill of one of the gabled houses at 10 rue Daviel, known appropriately as Petite Alsace. Or to trip down the cobbled rue Samson as it nears the rue de la Butte-aux-Cailles, racking your brain to recall which Jean Renoir film must have been set here. The architecture is modest, with none of the furbelows of monumental Paris, but it’s easy to imagine—or is it hear?—Georges Brassens melodies cooing from radios. Some of the Cailles’s streets perpetuate good country names—“Mill in the Meadows,” “Poplars”—seeming to defy the misguided urban planners of the sixties and seventies who permitted high-rises to be built not far away, like grim reality checks.

In your wanderings, you may sight residents loping with laptops to nearby lofts bowered by chestnuts, or backpack-encumbered Madelines sailing home from school unaccompanied in the quiet streets. In fine weather, the pharmacist, who elsewhere in the city would spend his quiet time officiously tidying, here takes the air, leaning against his doorframe, gossiping until a customer appears. And in a city that has at least three restaurants called Chez Paul, the Butte-aux-Cailles’s Paul, with its lace curtains and traditional grand-mère food, may be the most appealing. But then neighborhood standards are high, hoisted there by the inventive cooking of Christophe Beaufront of L’Avant-Goût.

Clear on the other side of town, Les Batignolles also began life beyond the city’s walls, on barely cultivated land. Here, in the 1820s and 1830s, developers constructed modest country retreats with patches of garden for the growing class of prosperous Parisian shopkeepers, who were soon joined by petty bureaucrats and washerwomen.

Everything and nothing changed with the coming of the railroads. The Paris–Le Pecq line, completed in 1837, cut the area off from the west. When Les Batignolles was annexed to Paris, Baron Haussmann’s engineering alter ego added a handsome park, the Square des Batignolles, but did little else to knit the backwater into the wider urban fabric. Low rents and an ample supply of laundresses and seamstresses willing to model attracted painters like Manet and Renoir. From 1865, they made the Café Guerbois and the Cabaret du Père Lathuille, on what is now the avenue de Clichy, the crossroads of artistic café culture, attracting Bazille, Degas, Pissarro, and Monet. But painterly Paris soon moved on, leaving Les Batignolles very much to itself.

Until lately. These days, two-career couples, delighted by its retro rents and sleepy, shabby-chic atmosphere, are snapping up apartments here. The neighborhood’s easy rhythms seem a world removed from the pressures of the Place de l’Opéra, little more than a mile away. Many residents find they can even walk to their law offices and banks. The organic market, held every Saturday just nearby, is yet another draw.

Like any French village worth its salt, Les Batignolles has a fine church standing at its heart. A semicircle of buildings frames the pretty place around neoclassic Sainte-Marie des Batignolles. The corner café boasts the confident name of L’Endroit and, within its varnished concrete walls, is every bit as edgy as the Café Guerbois was in its day. The trees along the southwest side of the church shelter a handful of timeless shops: a florist, a dealer in pretty bibelots, and a children’s outfitter with the sanguine name of Merci Maman. (Truth told, the children playing in the shadow of the boules game in the square beyond do look as though they mind their manners—but then more than a few of the newer Batignolles parents grew up in the strict and starched purlieus of the sixteenth arrondissement.)

The rue des Batignolles is the main drag, lined with pleasant boutiques, the local town hall, and restaurants. Then there’s the tree-lined rue Brochant, where you can admire the gilded curlicues on the Boucherie du Square, sample Christian Rizzotto’s ethereal cinnamon ganaches, and investigate the antique dolls at L’Atelier de Maïté. And at afternoon’s end, when the food shops reopen, you can eye supper along the rue des Moines, stopping at the tiny Fromagerie des Moines to nibble Saint-Marcellins and Pont-l’Évêques. In this neighborhood, even doing chores is a sensory delight.

Trend spotters say the Bastille is over as the mecca of haute hip, but their divinations cut no mustard at the Marché d’Aligre. Tucked away just a bit east of Carlos Ott’s behemoth opera house, the market has been the hub of a skilled artisans’ quarter for centuries. Newcomers may be more of-the-moment, but as far as the stallholders are concerned, last year’s pashmina passion will provide next year’s stock for the secondhand clothes dealers—and everybody will have to go on eating.

In a city of legendary markets, the Marché d’Aligre is unique in that it includes a street market, a covered market, and an open-air flea market (open six days a week). Named for the wife of Étienne d’Aligre, a worthy seventeenth-century chancellor, the market once rivaled the old Les Halles.

Today this is one of the city’s most integrated neighborhoods. And the next new thing—be it in blown glass, strié velvet, or neon tubing—will likely emerge from the workshops in the small passages that honeycomb the area. A handful of the cabinetmaking trades that were the backbone of the area remain, but many of the workshops are now ateliers for a new breed of supercharged creators. By day they hunker down at work; at night they play. The modern street section of the market, strung along the rue d’Aligre, is reputed to offer the city’s best values. Which, to an extent, explains the diversity of the crowd: graceful Malian women haggle with Tunisians over plantains, comme il faut students from the nearby law school stock up on apples and vintage frocks, and gay couples fill their shopping carts. Some of the merchants are specialists, like the fellow who deals only in garlic, shallots, and onions, or the mother and daughter who have for decades pyramided the north corner of the place with lettuce and herbs.

The covered market, the Marché Beauvau, might as well be in la France profonde. Here, a suckling pig turns on a butcher’s spit, and the scent of spices and fragrant oils floats out from the stall known as Sur les Quais. Outside, on the eastern edge of the square, secondhand dealers spread life’s castoffs. The merchandise looks little different from that on offer in a 1911 Atget photo of the area, save for the fact that a brutalist concrete apartment-building-cum-ground-floor-supermarket has replaced the triperie and greengrocer. And there are treasures to be unearthed. Occasionally there is a trove of flirty thirties bias-cut dresses in silk crêpe. Snapped up, they may soon clothe a lithe form sambaing at one of the area’s many hot nightspots. At noon, market habitués often heap their bags in a corner at a nearby wine bar or head for the hypercool Le Square Trousseau. This centenarian bistro hasn’t allowed its head to be turned by its new, big-name clientele. That may be Jean-Paul Gaultier tucking into petit salé (salt pork with lentils) over there, but that’s only reasonable: his Faubourg Saint-Antoine store, installed in a former furniture showroom, is just around the corner.

The rue du Cherche-Midi, on the western edge of the sixth arrondissement, is not laid-back. Here, rail-thin blondes swing leather-clad hips out of tiny Mercedes Smart cars and bolt into Eres to scoop up bikinis. More conservative types saunter from boutique to boutique, weighing the merits of saddle-stitched handbags from Il Bisonte against the frivolity of fur-trimmed microfiber sacs from Ginkgo. Down the street, every passerby lusts after the Andrée Putman armchairs at Hugues Chevalier, and there are nouveau-rustic wrought-iron lamps and door furniture at La Maison de Brune, not to mention every manner of stylish footgear at the ultrahip Lundi Bleu.

Following the route of a Roman road that once led from Lutèce to Vaugirard, the rue du Cherche-Midi today serves as a new kind of link. It bridges two styles, serving both the fashionistas who flock to Saint-Germain and the BCBGs, a hardy breed of French preppies, many of whom nest in the seventh arrondissement. Whatever their fashion icons, this shopping sorority can’t resist the siren allure of the Cherche-Midi vitrines.

The street’s retail charms are so conspicuous that they almost obscure what is one of the city’s most sought-after neighborhoods. Some of the capital’s most gracious apartments sit above the boutiques, carved from eighteenth- and nineteenth-century private houses. The “happy few” occupy aristocratic family mansions—some have been in the same hands for two hundred years. Other inhabitants, whom we might call limousine liberals but whom the French refer to as gauche caviar, choose the quartier for the grandeur of its fine houses and its access to the Collège de France and the other cultured haunts of the Left Bank.

The handsome balconies at no. 11 merely hint at the gilded splendor of the Louis XV paneling in its second-story reception rooms, and the nearby rue du Regard typifies the best of the sedate eighteenth-century limestone façades of the neighborhood, with elegant pediments and portes cochères that spark fantasy.

But the real magic of the neighborhood, what brings us back, is the people—the Little Blue Riding Hood employing Cartesian arguments to persuade Maman that the bear beanbag in the window really requires immediate adoption; the tailored gentleman looking the part of a retired diplomat, emerging from his bookbinder with a leather volume under his arm.

And amid all the fashion temptations, there are food shops (this is Paris, after all). The neighborhood baker is the internationally known Poilâne, the city’s largest organic market is held on the boulevard Raspail each Sunday, and the Grande Épicerie de Paris is only streets away. There are restaurants and cafés, too, though visitors are well advised to reserve if they hope to claim a table at L’Épi Dupin. Alternatively, they can join the ladies who don’t really lunch for a sandwich at Cuisine de Bar, where there’s even a diet choice. In this quartier, it’s important to be able to slither into a bodysuit from Feelgood.

Recently remodeled, the Musée des Arts et Métiers showcases French inventions, among them Pascal’s adding machine, Foucault’s pendulum, Ader’s airplane, and the Lumière brothers’ movie camera. (60 rue Réaumur / +33 01 53 01 82 00.)

Chez Omar is something of a hybrid: a nicotine-soaked brasserie specializing in couscous. Its clientele is equally eclectic, with models waiting for tables alongside locals, and cutting-edge moviemakers as pleased with the merguez as the wanna-bes. (47 rue de Bretagne / +33 01 42 72 36 26.)

The fare at Au Bascou is as good as Basque food gets: chestnut soup, stuffed piquillo peppers, and roasted squab, enjoyed with whatever little-known bottles Jean-Guy Loustou, the restaurant’s owner and host, may suggest. (38 rue Réaumur / +33 01 42 72 69 25.)

Le Pamphlet’s prix-fixe menu includes happy innovations such as squid risotto, crab ravioli sauced with pea emulsion, and licorice ice cream. (38 rue Debelleyme / +33 01 42 72 39 24.)

A huge, flat-screen monitor greets arrivals at Web Bar. With its concrete tables, velvet banquettes, and wired workstations, this is a grown-up cybercafé. (32 rue de Picardie / +33 01 42 72 66 55.)

Behind a shabby façade, DOT (Diffusion d’Objets de Table) sells reproductions of bistro tablewares. (47 rue de Saintonge / +33 01 40 29 90 34.)

There’s nothing shy about Philippe Ferrandis’s fantastical bijoux. Once an accessorist for Oscar de la Renta, today he makes and sells his bold and bright objets from this showroom-atelier. (2 rue Froissart / +33 01 48 87 87 24.)

In Franck Delmarcelle’s Et Caetera, you’ll find huge garden urns alongside eighteenth-century tables, and lanterns and mantelpieces alongside sideboards and chandeliers. Everything in this long, narrow boutique is gutsy and slightly overscale. (40 rue de Poitou / +33 01 42 71 37 11.)

L’Habilleur stocks last season’s merchandise, but the men’s and women’s duds all reflect the most wearable trends and are displayed in handsome, civilized surroundings. (44 rue de Poitou / +33 01 48 87 77 12.)

Agence Opale, a photo agency that specializes in portraits of authors, stocks prints of period photos of literary heroes. (8 rue Charlot / +33 01 40 29 93 33.)

Picquier et Protière sells its Marimekko-style fabrics by the yard but also makes them into cushions and stunning shopping bags with stout leather handles. (10 rue Charlot / +33 01 42 72 39 14.)

Galerie Yvon Lambert has been ahead of the curve since the late sixties, spotting Cy Twombly and Richard Long early on. It represents, among others, Nan Goldin. (108 rue Vieille-du-Temple / +33 01 42 71 09 33.)

The Place de la Commune de Paris commemorates the Butte-aux-Cailles’s role as headquarters for the insurgents in May 1871. Its bloody history is curiously at odds with the graceful, green cast-iron Fontaine Wallace that today stands in the middle of the tiny place.

A brick façade with late Art Nouveau sinuosities disguises the Piscine de la Butte-aux-Cailles, a municipal swimming pool fed by a bubbling artesian well. Roofed in then-innovative reinforced concrete, the pool, surprisingly, was built at the same time as the façade—in 1924. (5 place Paul-Verlaine / +33 01 45 89 60 05.)

At L’Avant-Goût, Christophe Beaufront’s luncheon menu, often featuring a luscious pig’s-cheek stew, has raised the bar for Paris’s néo-bistros. (26 rue Bobillot / +33 01 53 80 24 00.)

Chez Paul’s traditional French cuisine attracts people from all over the city. (22 rue de la Butte-aux-Cailles / +33 01 45 89 22 11.)

Les Abeilles sells dozens of honeys, along with supplies for beekeepers. (21 rue de la Butte-aux-Cailles / +33 01 45 81 43 48.)

Aux Délices de la Butte is the quintessential neighborhood bakery, with cannelés de Bordeaux and baguettes worth seeking out. (48 rue Bobillot / +33 01 45 89 45 55.)

La Cave du Moulin Vieux specializes in wines from small producers. (4 rue de la Butte-aux-Cailles / +33 01 45 80 42 38.)

You don’t have to be Italian to appreciate the salamis and aged Parmigiano-Reggiano at the Bologna-comes-to-Paris grocery Cipolli. (81 rue Bobillot / +33 01 45 88 26 06.)

Foursquare yet understated behind its four Doric columns, Sainte-Marie des Batignolles has stood since 1830 at the heart of the village of Batignolles. (77 place du Dr.-Félix-Lobligeois / +33 01 46 27 57 67.)

At L’Endroit, the of-the-moment hangout across from the church, the food tends to be as high design as much of the crowd, and the music crescendoes well into the night. (67 place du Dr.-Félix-Lobligeois / +33 01 42 29 50 00.)

It’s wise to reserve one of the twenty-odd seats at La P’tite Lili, where locals go to chill out. The menu is limited, but the sausages are flavorful, the salads sassy, and the meat and fish excellent. (8 rue des Batignolles / +33 01 45 22 54 22.)

Families sate their pasta passions at Arcimboldo, where they go en masse to share gnocchi and ravioli and wash it all down with Chianti. (7 rue Brochant / +33 01 42 29 37 62.)

The market-fresh food at the Cinnamon Café—tomatoes stuffed with whiting mousseline, apple crumble—is the stuff of memories. (5 rue des Batignolles / +33 01 43 87 64 51.)

Merci Maman carries the sort of handsome, sturdy clothes you see on Paris schoolchildren. (73 place du Dr.-Félix-Lobligeois / +33 01 42 29 11 62.)

The tiny candleholder that will make a table sparkle, the little present worth stashing for next December—such bibelots are the stock-in-trade of La Vie en Rose. (73 place du Dr.-Félix-Lobligeois / +33 01 42 63 70 71.)

The jury’s out on which is better: Christian Rizzotto’s cinnamon ganaches or his rocailles. (14 rue Brochant / +33 01 42 63 18 70.)

The Fromagerie des Moines is particularly strong on Norman cheeses like Camembert and Pont-l’Évêque. (47 rue des Moines / +33 01 46 27 69 24.)

For thirty-three years, L’Atelier de Maïté has specialized in buying, selling, and repairing dolls made between 1860 and 1930. (8 rue Brochant / +33 01 42 63 23 93.)

Opera fans thrill to visits backstage at Carlos Ott’s Opéra Bastille. The workrooms and full-scale rehearsal studios kindle lyric fascination. (120 rue de Lyon / +33 01 40 01 19 70.)

The Marché d’Aligre is the only Paris market open six days a week. It includes a street market, a covered market, and a flea market. Open Tuesday to Sunday, 8 a.m. to 1 p.m. (Place d’Aligre.)

Le Square Trousseau is headquarters for many of the Bastille area’s trendies. The food runs from comfort (terrines and tarts) to winds-of-change world food (risotto, chicken b’stilla). (1 rue Antoine-Vollon / +33 01 43 43 06 00.)

Sunday mornings are the choicest time at the wine bar Le Baron Rouge. Where else can you eat Arcachon oysters off the hood of a parked car while tasting Cairanne from Richaud? (1 rue Théophile-Roussel / +33 01 43 43 14 32.)

After a hard morning’s trade, shoppers and merchants collapse at La Table d’Aligre to savor sophisticated country cooking. (Place d’Aligre / +33 01 43 07 84 88.)

Whether you need a plum-colored sou’wester or a sequined pink beret, La Sartan is the Mad Hatter’s Parisian outpost. (24 rue de Charenton / +33 01 53 33 09 09.)

Michel Moisan has made his name as an organic baker; his walnut-hazelnut bread brings many across town. (5 place d’Aligre / +33 01 43 45 46 60.)

Spices and oils scent the entire Marché Beauvau thanks to Sur les Quais, which stocks at least a dozen vintages of olive oil—from Marché Beauvau, Sicily, Andalusia, and the Peloponnese. (place d’Aligre / +33 01 43 43 21 09.)

À la Providence is the place to buy French-style furniture hardware. (151 rue du Faubourg St.-Antoine / +33 01 43 43 06 41.)

Unlike some cutting-edge designers, Nathalie Dumeix creates for the less-than-anorexic. Zip into a vampy, bias-cut crêpe dress. (10 rue Théophile-Roussel / +33 01 43 46 00 22.)

Lionized by Second Empire hostesses for his flattering portraits, Ernest Hébert would largely be forgotten today but for the handsome eighteenth-century Petit Hôtel de Montmorency-Bours, which houses the Musée Hébert, dedicated to his works. (85 rue du Cherche-Midi / +33 01 42 22 23 82.)

The lunchtime crush at L’Épi Dupin is real, but so is the lunch, rich with chef François Pasteau’s inventions. Try the lamb enveloped in thin slices of eggplant. (11 rue Dupin / +33 01 42 22 64 56.)

Cuisine de Bar makes open-faced sandwiches of foie gras and shrimp on Poilâne’s famed sourdough, to be washed down with a fruit-juice cocktail. (8 rue du Cherche-Midi / +33 01 45 48 45 69.)

Finely finished leather handles top the bright microfiber handbags at Ginkgo. Some even sport fur collars. (4 ter rue du Cherche-Midi / +33 01 45 44 90 87.)

Feelgood lives up to its name, selling flirty dresses and good-value bodysuits, made of low-shine microfiber, that sculpt the shape. All emerge from suitcases looking as well rested as the wearers would like to be. (9 rue du Cherche-Midi / +33 01 45 44 88 66.)

At Elena Cantacuzène, ethnic styling meets catwalk chic. A handful of her beady “jools” are available in special American stores, but here you select from the full range. (47 rue du Cherche-Midi / +33 01 45 44 95 94.)

Under the gaze of passersby, Pierre Marsaleix binds books. He’s pleased to fill special orders based on sketches, and stamps volumes in elaborate designs. (113–115 rue du Cherche-Midi / +33 01 42 22 12 13.)

Célimène Pompon deals in what the French quaintly call travaux de dames, or needlework. Among the handsome original cross-stitch canvases, you’ll also find beguiling stuffed animals. (41 rue du Cherche-Midi / +33 01 45 44 53 95.)

Taken with sleek Normandie-inspired furnishings? Hugues Chevalier displays a tempting array. (17 rue du Cherche-Midi / +33 01 45 48 69 55.)