17 Peveril Road, Peel, after modernizing. Even its number and the name of the road itself have changed. The escape tunnel from the camp was dug from the front room and surfaced in the narrow path shown in the foreground

A Long Way Round

In only one other escape attempt did men succeed in getting off the Isle of Man, and then their stormy journey ended in failure. They too were a trio, but they were of a very different calibre from the three who had put to sea from Castletown. Intelligent men, consisting of two ship’s officers from the Dutch mercantile marine, and a Dutch civilian air pilot, they were pro-Nazi, and they escaped from Mooragh Camp, Ramsey, on the night of Wednesday 15 October 1941. Details of their escape from Ramsey are conflicting, and it is probable that the most accurate account was provided by an acting sergeant in the CID of the Manx police who later accompanied them back to camp and had ample opportunity to get at the facts.

The report of the case lists them as having escaped from camp sometime between six o’clock on the Wednesday evening, when they were present at the rollcall, and nine on the Thursday morning, when they were found to be missing and the alarm was immediately raised. In reality they had escaped at about half-past nine at night.

They admitted to the police sergeant that they had planned to get out for about two months, and they had certainly planned carefully. Then abruptly they learned that on the Thursday they were to be transferred to Peveril Camp. They disliked this idea, and escape during the Wednesday night became imperative, regardless of weather conditions.

They had built themselves a ladder with which they could climb to the top of the barbed wire. They had also lashed together two lengths of wood long enough to make a crude bridge across the top of the two lines of wire, from which they could then jump down to freedom. They had it all worked out; they even studied Ramsey Harbour during their official exercise walks and had spotted the yacht Irene and made a mental note of the position of a rowing-boat they could use to get out to her.

The plan went wrong, but this did not prevent the escape attempt. The ladder, which had been hidden in a lavatory, had disappeared. It had doubtless been found by the military and removed. This meant that they could no longer hope to climb up and over the wire. The men, however, had time to acquire a pair of pliers. They had already kept careful watch on the movements of the guards and knew the time between their appearances at a key point. They also noticed how the guards tended to take shelter in their huts on rainy nights, extending the interval between patrols.

The night of the 15th was a bad one, with a Force 10 gale, and the trio realized that the weather was against them. The prospect of a move to Peveril decided things. They cut the wire at grass level and were through.

Within ten minutes of escaping they were on board the yacht Irene. They later told the police that they distantly remembered hearing the noisy departure of men leaving a pub near the other side of the Swing Bridge. This suggests that it was about closing time, ten o’clock. The trio had armed themselves with a wooden pole from the camp. It enabled them to steer the small rowing-boat across the harbour to the yacht. They then cut the mooring ropes and left the dinghy tied up in place of the yacht.

The Irene had been correctly immobilized, but the tide was ebbing. Just as they had used their pole to steer across the harbour, so they used it to get the yacht clear to the sea, setting the sails as they did so. The rest must have been a nightmare, particularly for the air pilot. But off they steered for Ireland.

The Irish Sea in late September had been much too much for the three detainees who had escaped from Peel. Even though the Dutch trio included two experienced sailors, they were helpless in a powerless yacht when that same sea was running one of its autumnal storms with a south-westerly gale.

There is a strong implication that the British services played a cat-and-mouse game in what subsequently happened. As soon as the alarm was raised, a motor launch with an armed crew and police put to sea, and RAF aircraft combined with three naval patrol vessels from the island in a systematic sea search. The escape alarm system had worked with great thoroughness; boats were searched before leaving the island, just in case the trio had put back to shore and somehow made their way on to a passenger ship or a fishing-boat. The port authorities were alerted at Fleetwood and arrangements made to comb through the Steam Packet’s vessel as soon as it arrived there from Douglas.

A massive search was carried out on the island. The Home Guard, special constables, scouts, sea scouts, cadets and police themselves all combined in one operation, while coastguards and port authorities kept special watch. Airfields and military installations had been advised, and the whole elaborate alert system was in operation.

Visibility was bad; the seas were described as ‘mountainous’. The chance that an incapacitated yacht could cross westwards was virtually nil, especially considering the condition of the crew, without food, without proper shelter and without warmth. Precisely when they were spotted is uncertain; such details as remain are ambiguous. ‘The following day’ could have been the day after the men were last known to be in camp, or the day after they were declared missing. It could have been Thursday or Friday. At any rate, the RAF from a local station sighted the yacht and reported her.

No attempt was made to board her. The mouse was trapped; the cat may have been at play. The position of the yacht was precisely known, as were the conditions of the sea. The fact that she was helpless against the westerlies was obvious. It was only necessary to keep an eye on her. It was approaching midnight on Saturday when the Ramsey yacht, outward bound for Ireland, grounded on a small creek near Eskmeals, south of St Bees Head on the coast of Cumberland. The three men from Mooragh scrambled ashore, exhausted and ravenous, their clothing saturated. They were soon arrested, which, considering the lateness of the hour and the sparseness of the area, suggested that they had been watched for some time. The yacht was undamaged and later returned to the Isle of Man.

They were allowed to change into dry battledress and were taken to Whitehaven under military guard and handed over to the police. A Manx police escort arrived on the first boat and took them back to Douglas. The established procedure then followed. The trio were taken back to Ramsey and returned to camp. They were then arrested after the paperwork was completed, and charged with stealing the yacht Irene valued at £300. In their statements it turned out that their intention was to contact the German Consul in Dublin in the hope that he could arrange their return to Holland. They seemed proud of their escapade, claimed to have laid their plans well and were convinced that they were foiled only by the fierce storms. They seem not to have realized that their westward journey had covered roughly thirty-five miles eastwards at half a knot.

At their trial they pleaded Not Guilty to stealing the boat, saying that they had merely borrowed it to travel to a neutral country. They intended to arrange through the German Consulate in Dublin that the Irish authorities would return the boat to the owner or advise him where it was to be found.

The Manx police revealed that when arrested one of the men, not the air pilot, was found to possess a sketch map, in ink, of the Isle of Man and the east coast of Ireland, with some appropriate nautical details.

Despite their plea of innocence, the men each received six months’ prison sentences. They were graded as Second Class Offenders in the Manx gaol, which meant that they had never previously been convicted and were subject to the prison’s ordinary rules but had a more varied and liberal diet than citizens in the third class.

After serving their sentences they were released and were returned not to Mooragh Camp but to Peveril in Peel, to avoid which transfer they had timed their escape all those months ago. It had taken them quite a time to get there.

17 Peveril Road, Peel, after modernizing. Even its number and the name of the road itself have changed. The escape tunnel from the camp was dug from the front room and surfaced in the narrow path shown in the foreground

The right-hand post and iron hinge of the gate at 17 Peveril Road, Peel, are the same today (above) as they were then, when barbed wire spread out in front of the house (middle). The guardhouse can be seen (below right); the picture was taken following the discovery of the tunnel which came out in the narrow path, still there today. The guardhouse has been moved a mile along the road

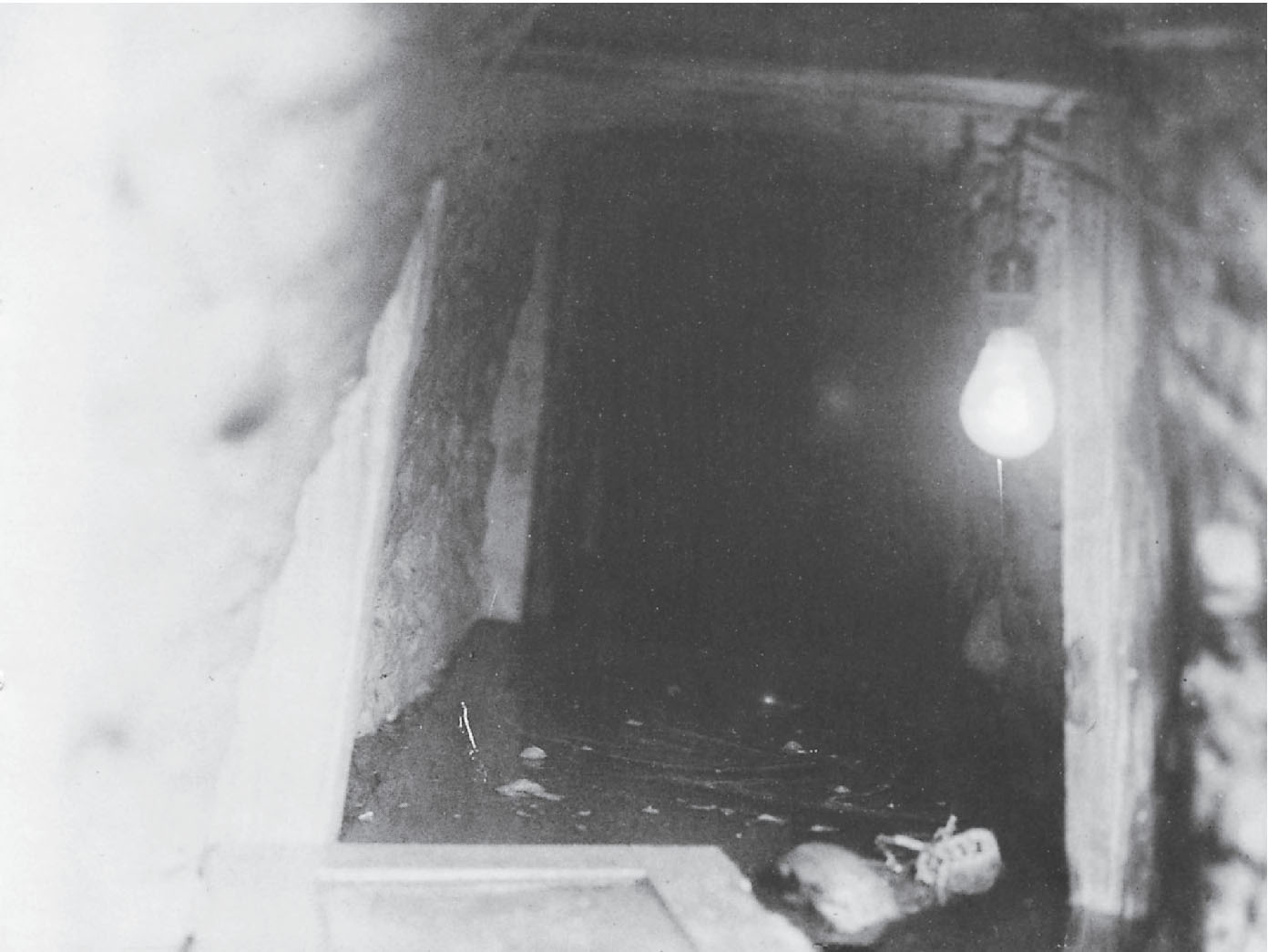

Original photographs taken from inside the front room of 17 Peveril Road on the discovery of the escape tunnel from the Peveril Camp on 29 September 1941. The shoring-up of the walls and the running of an electric light cable are clearly shown (above). The cutting of the joists under the ground floor and the ten-foot descent into the tunnel are seen in the lower picture

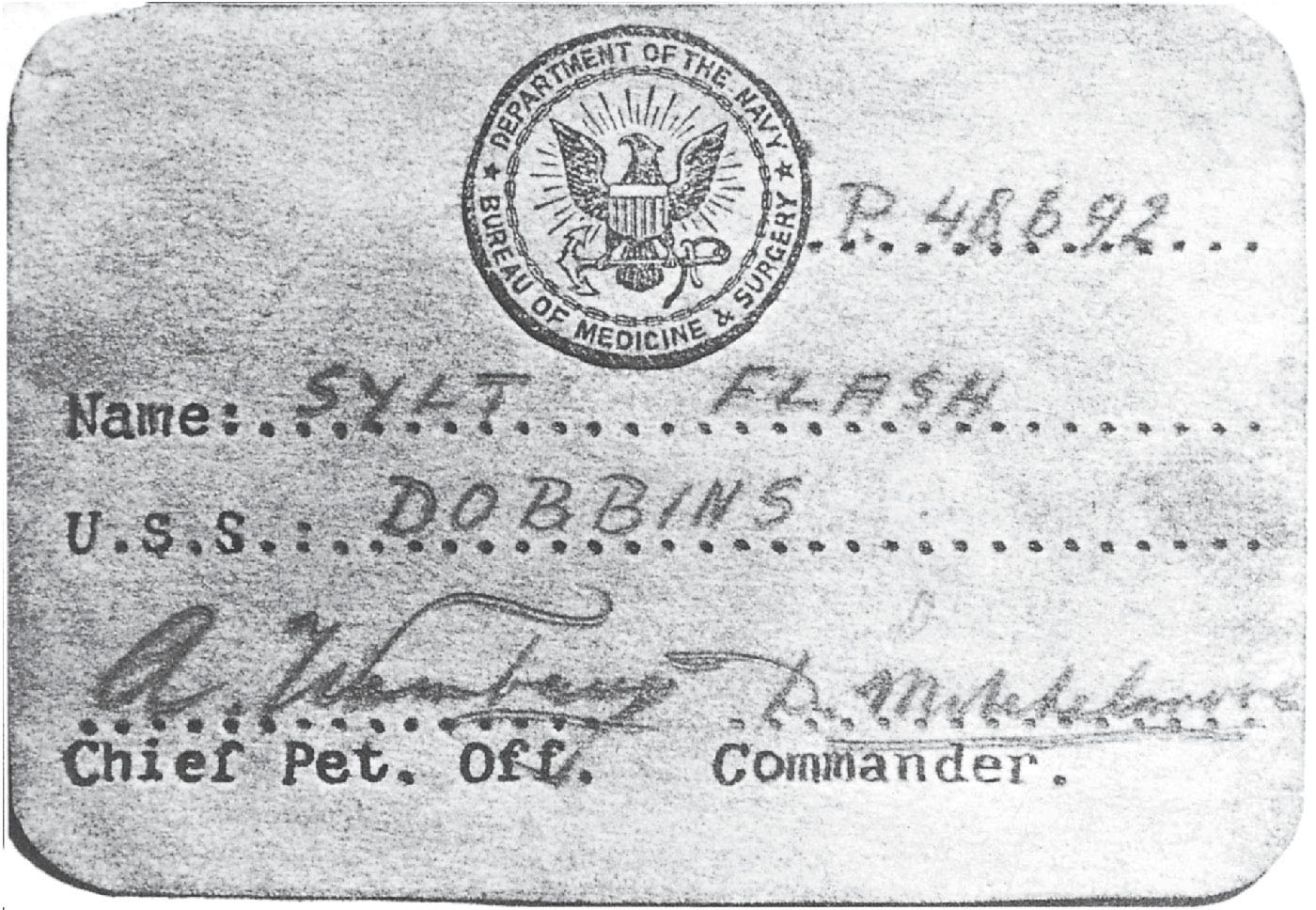

Forged US naval passes found on two internees who were caught in an escape attempt from Peveril Camp, Peel. ‘Haggit’ tried to tear up his ‘pass’ when arrested