Figure 2.1 Judy Malloy giving her Traversal in her office at Princeton University in September 2013 for the Pathfinders project.

Figure 2.1 Judy Malloy giving her Traversal in her office at Princeton University in September 2013 for the Pathfinders project.

Judy Malloy’s Uncle Roger is a pioneering work of early digital literature. Known for its connection to the San Francisco avant-garde community surrounding the Art Com Electronic Network (ACEN) on The WELL and for its innovative approaches to storytelling, Uncle Roger provides insight into the Silicon Valley computer-chip industry during the 1980s and so remains of interest to scholars involved in digital technologies today. Criticism of Malloy’s work has focused on her storytelling prowess (Flores), and scholars have additionally commented on Uncle Roger’s place in the literary canon (Berens 2014; Rettberg 2012), and the work’s computational features (Wilson 2001; Barnet, 2013, 121). Malloy herself has written about Uncle Roger on her electronic journal Content | Code | Process (2014, “Notes on Uncle Roger”), and has documented its history in interviews (McKeever 2014a, 2014b).

While collecting and producing the material about Uncle Roger for our multimedia book Pathfinders, this author was struck by the different ways Malloy told the story. She first published it on The WELL as a digital serial novel, but even as she performed the lexias for her audience,1 Malloy was already programming the story as a work of online interactive fiction and as a database novel for use as standalone software for Apple IIe and IBM-compatible computers. Close to a decade later, when browser software was introduced, Malloy recreated Uncle Roger as a Web-based hypertext fiction. Most recently, she produced the work for DOSBox, an emulation program. Recognizing distinctive features for each iteration of Uncle Roger, we organized these into versions based on her approach, the platform for which it was created, the programming or code used to create it, and variations to the story itself. While Malloy identified four versions of Uncle Roger in her interview with Alice McKeever (2014a), a detailed study of the work reveals that there are actually six digital versions. These include:

Because the focus of Pathfinders was to document and provide commentary about the works rather than to offer in-depth criticism, we did not give a detailed rationale for our strategy while the project was underway. With so many variants of Malloy’s work produced, it is important to know the differences between them because insights gained from this knowledge not only shed light on her artistic practice but also reflect cultural changes that affected her literary expression. Herein lies the focus of this essay.

As a work of experimental digital literature, Uncle Roger has always been articulated in code, and it was always intended to be experienced on computers. An accomplished programmer, Malloy did all of her own coding for Uncle Roger. Having studied systems analysis at the University of Denver, she learned FORTRAN during her years with Ball Brothers Research Corporation in Boulder, Colorado (Malloy, email to Grigar, July 3, 2015). Later she taught herself to write UNIX Shell Scripts, program in Applesoft BASIC and GW-BASIC, and code in HTML. She realized her interests in software development by producing “an artist’s personal authoring system” for Uncle Roger—Narrabase, built in UNIX and BASIC (Malloy, email to Grigar, May 24, 2015). Because of Uncle Roger’s born-digital status and Malloy’s emphasis on it as software for authoring digital literature, variants of Uncle Roger can indeed be seen as versions, where unique names pertain to unique states of the work. In Ex-Foliations: Reading Machines and the Upgrade Path, Terry Harpold talks about the importance of “register[ing] … differences where that can be done, and [attending] to what they might reveal of the historical arc of our reading” (2009, 3). This is the strategy we take in versioning Malloy’s Uncle Roger, and we do so by attending to changes to its form (e.g., serial novel to database narrative); platform (e.g., Applesoft Basic to GW-BASIC); and content (e.g., toning down sexual references for public access on the Web).

Gaining access to works created for computers and computer systems now obsolete poses challenges for scholars. The serial novel, for example, was conceptualized as an online performance not meant to be printed on paper and read (Malloy, email to Grigar, June 20, 2015). Only two copies exist, one held by Malloy and the other by the Judy Malloy Papers at the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Duke University.2 Likewise Version 2, the interactive narrative of Uncle Roger, was not preserved. Only recently has Malloy discovered in her own archives the necessary software to recreate it. Also complicating scholarship of Malloy’s work is the fact that her standalone artists’ software is stored on floppy disks unreadable on contemporary computers. But a handful of copies of Uncle Roger’s floppy disks remain, anyway, and the few held in the Judy Malloy Papers are restricted for digital preservation and cannot be read.3 For our own research we were able to borrow Malloy’s personal copy of Uncle Roger on floppy disk and read it using a vintage computer in this author’s lab.4 Comparing this copy with the Web and emulated versions, as well as examining Malloy’s comments about earlier work made in essays, interviews, and email exchanges, has helped to identify the six variants of Uncle Roger. In consultation, Malloy verified her agreement with this schema.

Our work demonstrates that Malloy approached each recreation of Uncle Roger as a unique work of art, conceptualizing it to take advantage of the affordances of the platform or medium on which it would reside and by which the audience would reach it. For close to thirty years, Malloy has kept Uncle Roger alive and accessible to her reading audience. At a time when Flash-based poetry and fiction created less than a decade ago are becoming unreadable on computing devices, this is no small feat.

As Malloy reports, the first version of Uncle Roger stemmed from an invitation she received in 1986 from her friend Carl Loeffler, founder of the La Mamelle Art Center and gallery. In operation from 1975 until 1995, the gallery specialized in avant-garde art arising out of the San Francisco scene and beyond and later evolved to include a cable TV series. Projects such as the 1976 Xerox art exhibit and 1977’s Send/Receive, a performance simultaneously broadcast in New York and San Francisco, established the gallery as cutting edge and Loeffler as visionary (“Elsewhere on the Net,” 2001).5 When Loeffler was introduced to the online community of The WELL upon its 1985 launch, he was inspired to expand his ideas about art and technology to the new virtual space. With performance artist Fred Truck serving as programmer, Loeffler launched ACEN in September 1986 (Malloy 2013, “Memories of Art Com and La Mamelle”). ACEN offered a host of resources, including an online exhibition space, art publications, retail store, and a conferencing system (referred to as a Bulletin Board System or BBS) that allowed for online interaction among the community members.6

The BBS was especially useful for sustaining online conversations about art. For this purpose, The WELL used PicoSpan, created by Marcus Watts in 1983 for the Unix operating system. As Malloy writes:

Initially, The WELL’s server was a VAX, located beside Sausalito harbor, at the foot of a dock, where colorful houseboats were inhabited by artists and poets. The conference software—the Unix-based PicoSpan computer conferencing system, written by Marcus D. Watts in 1983 and provided by Brilliant’s conferencing software company, Network Technologies International (NETI)—both enabled and organized virtual conversation. Although some users found PicoSpan’s learning curve difficult, once mastered, its flexibility and clarity fostered an environment of online community. (Malloy 2016, 27)

The BBS was structured so that participants stayed focused on a single thread. It also made comments impossible to censor. This last feature encouraged frank discussions about and approaches to art and resulted in open and lively conversations. In a 1997 Wired article, “The Epic Saga of the Well,” Katie Hafner reports:

PicoSpan didn’t simply foster openness but forced it on users. The program was designed so that everyone who signed up would be invited to write a personal bio of any length to reside permanently on the system. Another feature, known—somewhat illogically—as “scribbling,” allowed participants to delete their words after the fact. But the scribbled posting would appear as a new blank posting to everyone else in the conference. In other words, you couldn’t erase your words without others knowing about it. … Also, postings didn’t expire—that is, they didn’t self-destruct automatically after a certain amount of time.

Though slow by today’s standards, discussions did take place in hours rather than days, as they might via the US Postal Service, for example. “Feedback,” Loeffler felt, was “instant.”7 He also learned that the “‘community’ in the online environment was actually diverse” in terms of the audience’s background and training, “a pleasant surprise for an art organization interested in expanding the audience for contemporary art” (“Elsewhere on the Net,” 2001).

Thus, when Loeffler asked Malloy to “go online and write” in a venue hosting discussions on topics such as “Software as Art,” publishing work, and featuring “actual works of art … by John Cage, Jim Rosenberg, and others,” she jumped at the chance. For the nine years leading up to Loeffler’s invitation, Malloy had already been experimenting with art as “molecular … units” (Malloy 1991, 200), a notion that also described her nondigital work, such as her “3 × 5 inch cards or file folders full of information” (Malloy 1988, 371). On December 1, 1986, Malloy presented the first lexia of the seventy-five she created for A Party in Woodside, the first of two files associated with the serial novel. Malloy also posted “links associated with” the lexias. As she recounts, “The idea was that readers could pull the text and keywords into their own database software.” Howard Rheingold lent a hand and created “a parallel topic to discuss Uncle Roger and how to implement it” on Topic 15 (Malloy 1991, 200). “Some actually did,” Malloy reports. Over the course of the next forty days, until January 29, 1987, she posted at least one lexia of the serialized novel daily, taking advantage of PicoSpan’s single thread feature—“co-opting (with permission),” she recalls. The Blue Notebook, “file 2,” followed seven months later in July 1987 (Malloy 2014).

To access the seventy-five lexias comprising Version 1 today is not easy. For most it means travel to Duke University’s library. However, Malloy recounts the story in various places, and we know from interviews with her8 that Uncle Roger involves numerous plots and subplots relayed through the perspective of Jenny, a twenty-one-year old who works in the Bay Area as the babysitter for the wealthy Broadthrow family and becomes entangled in the intrigue involving Tom Broadthrow and his company, BroadthrowMicro. Tom, we learn in A Party in Woodside, has stolen a custom chip from Jeff Gallagher, a young man in whom Jenny claims a romantic interest. This plot rises to a climax in The Blue Notebook. Jenny, we learn, is the niece of the titular Uncle Roger, who is heavily implicated in the shenanigans surrounding the stolen chip. Jenny’s other stories, both fanciful and real, focus on relationships with other characters and the tensions resulting from conflicts arising from her personal experiences: her former lover David; her family back on the East Coast; the growing romantic involvement with Jeff; extramarital affairs between people with whom she comes in contact or knows well; the imagined destruction of Somerville, Massachusetts, by bombs dropped from blimps; caring for the child she is hired to babysit; and many more. However, Jenny is not a completely reliable narrator. In A Party in Woodside, she reveals that she drank too much wine and slept “fitfully,” her thoughts “interspersed with dreams.” In The Blue Notebook, she admits that what she is writing down—and so telling us about the story—is not “exactly” how the events happened. Malloy purposely takes this strategy. In the first file, Jenny, she says, is

telling the story as experienced in a night after where dreams mingle with reality, and the difference is blurred—and, in the second file, deliberately introducing elements of magic realism. It would be expected that elements in the work of artists like Carolee Schneemann, Chris Burden, and Kathy Acker would seep into my work or were parallel with my work. For years, by the way, I had a copy of [Richard Brautigan’s] Trout Fishing in America (“The waterfall was just a flight of wooden stairs”) on a shelf in my work area. It never occurred to me that it was an influence, but it was in the environment of my writing. In my work of that era, … I generally used unexpected settings, a Silicon Valley bedroom community for instance, a Falstaffian Semiconductor Systems Analyst. We could go back to Plautus. … The magic realism and explicit, dream-laced lexias of Uncle Roger worked well in the environment of ACEN. The immersive party in Silicon Valley environment also worked well for the wider WELL audience … (at least those who followed ACEN). (Malloy, email to Grigar, July 4, 2015)

The main conflict underlying Uncle Roger involves Jenny’s struggle to gain footing in the world and agency as an adult in an atmosphere where theft of intellectual property and destruction of people’s livelihoods, and lives, are the norm.

The dominant action takes place over several months and includes a party held at the Broadthrow home in September (A Party in Woodside) and a birthday party in honor of Tom Broadthrow at a restaurant in South Bay two weeks later (The Blue Notebook). Indulgence in large quantities of food and drink makes for rowdy festivities, but in this story about the heady world of the chip industry, where so much money is at stake, parties are also prime locations for intrigue and conflict. That the Broadthrow home frames the story for A Party in Woodside (and, in later versions, Terminals) places the Broadthrow family front and center of the action. Common themes emerge: journey, struggle for agency and independence, promise and betrayal of the American Dream, love, lust, revenge, and loss. Along with recurring characters, the party settings, and themes, we find motifs and symbols—sailboats, dreams, chips (silicon and potato), bodies of water (lakes and ocean), food, and colors—that contribute to the cohesiveness of a story told in increments over a course of eight weeks and continued seven months later.

The story struck a chord with Malloy’s Bay Area audience on The WELL. Many of those reading Uncle Roger themselves worked in some aspect of computing—some even in the semiconductor industry—and so were aware of the piracy taking place in the cutthroat business. More than likely, they were also familiar with Malloy’s allusion to a green background on a computer monitor reflected in Jenny’s comment: “What I type on the keyboard appears in green on the screen which is called a monitor” (Malloy, Terminals, Record No. 107). As Rheingold recalls in The Virtual Community, a “few hundred people” were members of The WELL when it began in 1985 (1993, 2), but it grew to into the thousands by 1994.9 Malloy’s audience, though exceedingly small in comparison to the number of people online today, included a considerable number of highly digitally literate people—or “digerati,” they were called (Hafner 1997). In 1983, the first year that Americans were polled about computer usage, for example, only 10 percent of households reported owning a computer; 1.4 percent reported using the Internet. By 1990, 42 percent of the population used computers. Studies suggest that the cost of computers lay outside of the budget of most Americans at the time (Fox and Rainie 2014). A brand new Apple IIe that members of Malloy’s audience may have used to access The WELL and read Uncle Roger sold for $1,395 in 1983, equivalent to $3,400 today. Malloy had begun using a personal computer in 1985 (Malloy, 1991, 196), and her own Apple II was purchased used from “the legendary Used Computer Store in Berkeley” (Malloy, email to Grigar, July 3, 2015). Feedback to the story, therefore, was possible because the audience was digitally literate and affluent and so quite capable of accessing it.

While the audience could not intervene in the story directly, audience members were able to respond to the topics Malloy and Rheingold prepared for them. Rheingold’s “parallel topic” (Malloy 2014), entitled “Feedback re: Uncle Roger,” was available alongside Malloy’s lexias and provoked responses to which she reacted like “any oral storyteller or performer.” In fact, Malloy claims to have “played to” her audience (McKeever 2014a). Printouts of responses in her personal files show an engaged and playful audience, much like those of Twitter or Facebook today. And like tweets and Facebook posts, WELL users’ responses ranged from advice to praise to flirtation. One user suggested, “If you don’t want to bother with computer databases, the way to use the story would be to print it on 4″ × 6″ cards.” Another writing a little later that day said, “Whatever it is, it sure promises to be sexy, and I’m all for sexiness.” To the futurist and fellow WELL user Tom Mandel, Loeffler wrote:

Post 12 on Topic 15: Feedback re: Uncle Roger

12: Artcom (artcomtv)

OK … Tom

What (?) jacket are you wearing???????????10

In fact, scholars consider this version of Uncle Roger, delivered as a serial novel, one of the first examples of online participatory literature (Berens, 2014, 343; Grigar and Moulthrop 2015).

The comment about the work’s “sexiness” highlights the fact that Malloy leveraged the openness of the system’s technology and the community’s adventurous nature to tell a story that contained a frank depiction of sexuality. If the serial novel resembles the story relayed in Version 3, as Malloy suggests, then the first lexia of A Party in Woodside, for example, may have read:

I dreamed that Jeff and I were in bed.

He was running his hands up and down my

body.

He put his tongue in my mouth.

His hands were on my nipples.

He ran his fingers down the inside of my

thighs. (APIW, Record No. 1)

Another lexia describes Jenny “put[ting her] hand on [Jeff’s] cock” in response to him “biting [her] nipples.” Still another has Jeff rubbing suntan oil down Jenny’s “ass.” Such graphic depiction of sex is rare today on public sites such as Facebook and Twitter. As recently as March 2015, Facebook censored benign information on sexual health (“Take a Stand against Censorship,” 2015), and Twitter blocked searches of the word “porn” (O’Hara 2015). Many of the lexias hinting at unacceptable conduct would not pass the censorship of either social media site. Incest and pedophilia, especially, figure largely in early versions of the story. In A Party in Woodside, Jenny recounts a story her cousin Anne shared with her involving Uncle Roger, who tied her “to a bed. … It was one of those beds with pineapples on the bedknobs.” Jenny learns that Uncle Roger then told Anne to “take off all [her] clothes,” which seems to be impossible in light of Anne being tied up. In another lexia Jenny reports that when she was a child, Uncle Roger asked her questions such as, “Have you ever seen a grown man’s penis?” In The Blue Notebook, Jenny overhears him pointing out “cute boys” to BroadthrowMicro’s lawyer, Bob Draper. Later, when Uncle Roger was distributed on the Web for a wider audience, references to this kind of behavior were dropped, and Uncle Roger emerges, instead, as a Falstaffian character full of mischief and mildly ribald humor (Malloy, email to Grigar, July 4, 2015). Such a change in tone reinforces the differences among the versions and demonstrates one of the ways the work changed as it moved on to larger audiences.

It is also important to note that even as a serial novel performed for an audience, Uncle Roger was created so that Malloy’s audience members could use “their own database software” and the “keyword field” that she produced for each lexia to read the work. This effort resulted in a story told nonsequentially and with a measure of interactivity (McKeever 2014a). Though this feature of Uncle Roger was not as visually appealing as Malloy had wanted (McKeever 2014b), she realized it in a more satisfactory way in Version 2, when she was able to control the look and feel of the online database readers used to access the work.

Version 2 of Uncle Roger, produced as an interactive work for Art Com Electronic Network’s Datanet and published 1987–1988, has been unavailable since the late 1980s. As mentioned previously, Malloy recently found the programs among her personal archives (Malloy, email to Grigar, August 25, 2015). Until she is able to recreate the work, all that is left of it are descriptions found in Malloy’s essays, interviews she has given, and email exchanges. For example, Malloy’s 1991 essay, “Uncle Roger, an Online Narrabase,” published in Leonardo, and her more recent “Notes on Uncle Roger,” published in Authoring Software, provide information about the story’s origins and Malloy’s production methods. The Leonardo article is also notable for providing images of each file’s main menu as well as sample records for file 3. Malloy’s 2014 interview with Alice McKeever for The Literary Platform, entitled “Judy Malloy on Narrabases,” sheds light on the programming behind the work. Personal email exchanges with Malloy have filled in gaps about how she handled editing (Malloy, emails to Grigar, July 2 and July 4, 2015). Along with this evidence, textual critics can tease out elements of the story based on other extant versions. The print-out of Version 1, which includes the first two files of Uncle Roger each consisting of seventy-five lexias, serves as the starting point for knowing what Version 2 would entail if we had access to it. Even more useful is Version 3. This boxed collection of standalone artists’ software, like Version 2, was built from the ground up as a searchable database and includes all three files, with files 1 and 2 consisting of the same number of lexias accessed through many of the same keywords as Version 2. While we expect works of fiction created thousands of years ago to be lost to us, it is worrisome to confront the disappearance of a literary work produced a mere thirty years ago and distributed over the net to hundreds of readers. That Version 2 was not preserved, its screens of lexias never captured for posterity, makes discussing the work challenging. So, what do we know about this version of Uncle Roger?

First, we know that Fred Truck had access to The WELL’s server and was able to perform feats of magic by making works published on ACEN Datanet interactive. We know Malloy took advantage of this new featureby recreating Uncle Roger from ground up as an interactive narrative (McKeever 2014b). We further know that labor on Version 2 began as early as 1986 while Malloy was creating and performing Version 1 (Malloy, email to Grigar, July 3, 2015). And we know that Malloy’s interest in databases did not emerge suddenly in 1986 while working on Uncle Roger but rather stemmed from a 1969 Ball Brothers project, which resulted in a citation-based database of engineering literature. We know the database she created as Uncle Roger sixteen years later was a full-text database with searchable lexias, or “records” (Malloy 1991, 196–197). As Malloy tells it, she was also in the midst of developing an Applesoft BASIC version of Uncle Roger for standalone artists’ software, a project that eventually became Version 3 of Uncle Roger, when both Loeffler and Truck asked her to create an interactive version for ACEN Datanet. To accommodate their request, she had to produce Uncle Roger as UNIX Shell Scripts, the format Truck was using to produce the menus for ACEN Datanet (McKeever 2014b). Truck also designed the system so that text was constrained to one to eighteen lines of text per screen and to a column length of fifty characters, a protocol that Malloy thought she had to follow though in fact there was no such constraint (Malloy 1991, 197; Malloy, email to Grigar, July 3, 2015).

Malloy has talked openly about the challenges she faced when reconceptualizing Version 1, the serial novel, as a system of records that could stand alone as individual units and function collectively as a whole, likening this experience to “a composer … composing four different streams of music that will eventually be heard together by the listener.” We can understand the not-so-subtle difference she makes between the two: unlike a musical composition, the database narrative made it possible for “each reader … [to] combine [the records] differently”; “all possible combinations had to be anticipated” (Malloy 1991, 197). To address this challenge, Malloy developed a short list of keywords derived from characters, places, and things found in Version 1’s A Party in Woodside and The Blue Notebook. Readers could type in one of the keywords and receive all of the records associated with that keyword. This approach to storytelling allowed Malloy’s audience to read the story in different ways depending on the keywords searched. Plots, characterization, conflicts and other aspects of the story unfolded nonsequentially, and audience interaction was derived from decisions readers made about which keyword to search. Though she sometimes referred to Version 2 as an interactive narrative (Malloy, email to Grigar, July 3, 2015), she was clear about the distinctions between Uncle Roger and adventure stories (interactive fiction), or hypertext works created with HyperCard and other digital technologies. Malloy thought her endeavors were better described as narrative databases, and to that end she coined the phrase “narrabase” (Malloy 1991, 198). She was out to make a work of art completely different than what was being produced at the time.

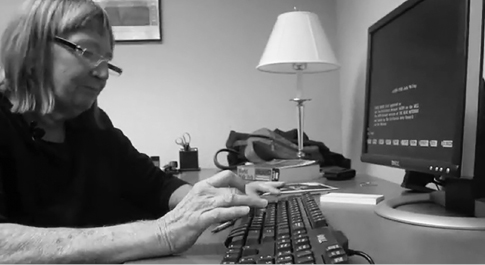

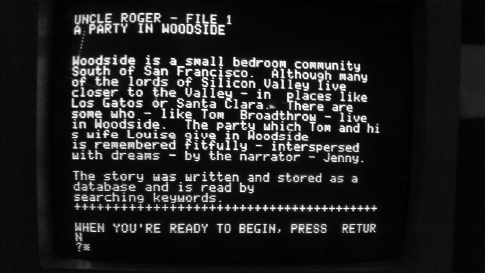

We know from the few screen captures available from the Leonardo essay that when Malloy’s audience entered the ACEN Datanet site for Uncle Roger, they were greeted with an interactive menu (figure 2.2) providing a brief description of the work and identifying it as a “three part interactive novel” meant to be read by “follow[ing] an individual path … [and] searching key elements called ‘keywords.’” Readers would also have seen a list containing the three files—with Terminals joining A Party in Woodside and The Blue Notebook as the third part of the story—and simple directions for accessing them. For example, typing “1” would result in the opening screen for “file 1,”11 A Party in Woodside. Within each file, readers would choose from the keywords and be off on an adventure about a world and lifestyle Malloy knew would suit their tastes and interests. If we can imagine 1987, a time before browsers and the Web, before robust graphics and sound, before memory and bandwidth could handle animation and video, before CDs, long before Facebook was even a twinkle in Mark Zuckerberg’s eye (he was three years old at the time), then we may be able to get an inkling of the innovations behind this version of Uncle Roger.

Figure 2.2 Main menu for Uncle Roger, Version 2.

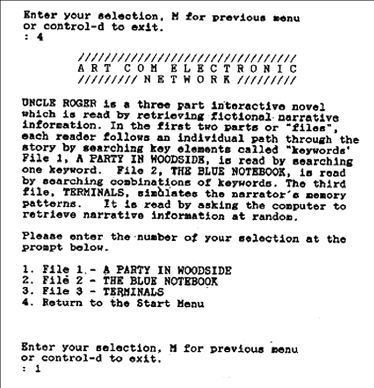

Malloy provided twenty-one keywords for A Party in Woodside (figure 2.3), over two-thirds of them referring to people with whom Jenny interacts or whom she remembers in her thoughts and dreams. Four abstract and concrete objects—“dreams,” “the house,” “chips,” and “refreshments”—also result in records that reveal parts of the story. “Puffy,” the Broadthrow’s cat, is the list’s only animal. Based on Version 3, Puffy injects humor into the story, meting out sly punishment to those deserving it.

Figure 2.3 Opening screen for A Party in Woodside of Uncle Roger, Version 2.

The Blue Notebook, listed as number 2 in the main menu, offered twenty-five keywords, listed by letters:

| a. Jenny | j. Dorrie | s. blue notebook |

| b. Jeff | k. Liz | t. bathroom |

| c. David | l. Dennis | u. restaurant |

| d. Uncle Roger | m. Jack | v. chips |

| e. Tom | n. Rose | w. beach |

| f. Louise | o. Mark | x. San Jose |

| g. cats | p. Caroline | y. Woodside |

| h. Linda | q. family | z. café |

| i. men in tan |

We see many names from the first file repeated, but several new characters are introduced—Linda, whom we know from Version 3 is David’s ex-girlfriend, with whom he may still be involved; Dennis, the consultant from Albuquerque that Tom brings in to solve a crisis at BroadthrowMicro; and Liz, a woman at Jeff’s office who may or may not be his lover. Places such as the “bathroom” figure as the site where Uncle Roger stages his clandestine meeting with Jenny and reveals his secret about the stolen chip; the “café,” the meeting place where Jenny casually runs into Jeff and sparks their romance; and the “restaurant,” where Tom’s birthday party is held. The focal point of the conflict is the stolen chip, and records relating to it can be evoked directly through the keyword, “chips.”

In terms of the story underlying Uncle Roger, we know that Malloy retained the seventy-five lexias of Version 1 for Version 2 and included new material in the form of the third file, Terminals (Malloy 1991, 200). We can surmise from her descriptions of the work in various essays and interviews dating back to 1991 (Malloy 1991, 198–199; Malloy 2014) that the story changed little in the shift from the serial novel to the interactive narrative. Moreover, if Malloy did edit Uncle Roger, she did so because lexias were “subservient to the work as a whole and … not a constraint that [she] felt it necessary to adhere to” (Malloy, email to Grigar, June 25, 2015). The addition of Terminals, which consisted of a hundred records, functions in the overall story as the name implies: an ending, finale, and termination of Jenny’s narrative. It also plays with the notion of a computer terminal, a metaphor for the world that Jenny now finds herself in.

Unlike Version 2 of A Party in Woodside and The Blue Notebook, which were created as databases, Terminals was built with the computer’s “pseudo-random number generator” so that readers could evoke records randomly by simply pressing the return key (Malloy 2014). Landing at its opening screen, readers found a brief narrative that contextualized the story from, once again, Jenny’s perspective:

In the room where I work, there are

about twenty desks called “stations”.

A computer takes up most of the space at

each station. Each computer has a

black screen which rests on a gray case,

and a keyboard which is attached to the

computer by a cord, like those cords which

hold the two pieces of telephones together.

They call the computers “terminals”. (Malloy 1991, 201)

They would also learned that Terminals offered a hundred “records” and that

the information is stored in computer memory and retrieved at random just as it might surface in the mind of the narrator. Sometimes one record will be repeated several times. Or, one part of the story will be submerged for long time—reoccurring unexpectedly. (Malloy 1991, 201)

To read the story, Malloy’s audience would simply have pressed the return key on the keyboard, over and over, accessing lexias comprising the story in a random manner. Malloy based her generator on the Unix date generator suggested by writer Gil MinaMora, which provided a “series of changing numbers” that “print[ed] out various records with some repetition.” She also programmed “some structure” into Terminals by building in a fixed opening and closing record. Once readers accessed the fixed opening, they would have been confronted with a work that proceeded randomly until they reached the closing screen (Malloy 1991, 201), an ending that may have been similar to that of Versions 5 or 6 where Uncle Roger shouts, “Merry Christmas,” and the lexia finishes with “The End.”

Malloy employed this mode of storytelling in order to produce a “less tightly controlled structure” and admits in essays about the work that “in the telling of Uncle Roger, technology—a computer database—is used to simulate the way technology both complicates and enhances our lives” (1991, 198–199). She also reports that she found the way the date generator expressed randomness “pleasing and desirable because it mimicked the way memories come and go, sometimes repeating, in one’s mind” (1991, 201). Therefore, in A Party in Woodside we may have chalked up Jenny’s unreliability to drinking too much wine and getting many nights of poor sleep, and in The Blue Notebook, to Jenny purposely fudging the facts. In Terminals we learn that she is plagued by dreams and memories to the point that we cannot always discern if what she is telling us is real. For readers who may have just experienced the previous two parts of the story, where control over the narrative was possible, the random display of records caused by Terminals’ keyword search would have simulated Jenny’s own confusion. Thus, Malloy’s approach to storytelling is aligned with the story itself, smoothly incorporating technique with content (Malloy 1991, 201).

Malloy recalls that when she launched the interactive version of Uncle Roger, it enjoyed much “buzz” and “interest” (McKeever 2014b). Because readers could have accessed the work directly online and interacted with it there rather than putting Uncle Roger into their own database software and querying it from their location, Version 2 “facilitate[d] immediate publication, was compatible with any computer with a modem, and integrate[d] the artist with the audience” (Malloy 1991, 195).

This differs from Version 1, which, as previously discussed, would have been downloaded by readers and accessed locally. The way the work was displayed would have been affected by the kind of software the reader used. Version 2, in contrast, controlled the user experience in that the database functionality was built into the work itself as part of the aesthetic. Thus, it took less time to access and enjoy and maintained the look and feel Malloy envisioned (McKeever 2014b).

Malloy had begun programming Version 3 even before she was called away to build Version 2 for ACEN Datanet (McKeever 2014a). Version 3 marks a major shift from the first two in that it involved creating Uncle Roger as standalone artists’ software programmed in Applesoft BASIC for Apple II computers. Called Narrabase, the platform was intended for the creation of database narratives. As in the previous versions, the story unfolds in seventy-five lexias. The copy of Version 3 we used for our research is missing Record No. 14 of A Party in Woodside. We can make a reasonable guess about this lexia’s content based on Versions 5 and 6, where it does exist. Malloy herself does not know why it is omitted from this file (Malloy, email to Grigar, June 25, 2015). That it is missing speaks to the labor it took to copy files in days before copy-and-paste, drag-and-drop, and right-clicking made it so easy to manipulate a large amount of data simultaneously.

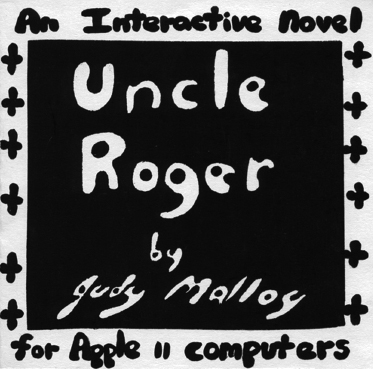

Beginning with Version 3, the works were published on 5.25-inch floppy disks and packaged in standard plastic boxes—except these boxes were designed with highly stylized labels and inserts created by Malloy.12 In fact, Version 3 reflects Malloy’s fine art practice, particularly her earlier work creating artists’ books. A copy of Version 3.1, the hand-made package of A Party in Woodside, is held by the Museum of Modern Art/Franklin Furnace/Artist Book Collection.13 Before information sharing was easily undertaken via the Web and cloud computing, a boxed collection of Uncle Roger that could be shipped to a gallery for exhibition was both innovative and pragmatic. Version 3 made it possible for Malloy to show Uncle Roger at festivals and gallery exhibitions in North America and Europe.

Figure 2.4 Malloy’s hand-designed insert for Uncle Roger.

As in Version 2, in Version 3 A Party in Woodside and The Blue Notebook are organized as records evoked when readers query a database using a set of keywords, and Terminals remains programmed as randomly generated text. However, Version 3 builds more functionality into the database by making it possible for readers to combine two keywords in a search.

A Party in Woodside was created first and constitutes Version 3.1 of Uncle Roger. Malloy updated this version to eradicate a few bugs and rereleased it in 1988. We see this updated file as Version 3.2. After she completed the programming for The Blue Notebook and Terminals, she packaged the floppy disks of all three files together and sold them as a boxed set for $15 through the Art Com Catalog.14 This collection constitutes Version 3.3. Versions 3.1–3.3 were produced specifically for Apple II computers and state as much on their packaging (figure 2.4).

The David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Duke University holds copies of A Party in Woodside, The Blue Notebook, and the complete Version 3.3. Stanford University also holds one copy of Version 3.3 in its Special Collections,15 and Malloy herself retains a copy of this version. The copy of Version 3.3 Malloy lent us is missing file 3. Thus only Duke, Stanford, and Malloy herself have copies of Terminals for Version 3.3. Because library collections restrict access to floppy disks due to digital preservation issues, there is no way today for anyone to read file 3 of Version 3.3 to know precisely what the story entails or how it may differ from other versions of it. The copy of Uncle Roger used for this essay represents, Malloy believes, a “second” not sent to Art Com Catalog in the late 1980s. A close examination of it for Pathfinders also reveals differences from the inserts distributed by Art Com Catalog (Malloy, email to Grigar, May 24, 2015). The copy does, however, contain all other items associated with Uncle Roger, including files 1 and 2. For this reason, discussions about Version 3.3 in this essay are limited to those two files.

Figure 2.5 Beginning of the message, “Bad Information,” displayed on the Apple IIe.

To read Uncle Roger, readers would have opened the plastic box, selected the floppy disk for A Party in Woodside, and loaded it into the computer’s drive. Once the drive was closed, readers would have needed to reach behind the computer to turn it on. As the Apple II or IIe booted up, it made a distinctive sound—a hum followed by a series of clicks. Bright green words, “Bad Information”16 produced in ASCII, briefly appeared on the dark green screen, giving way to a second screen that read, “Bad Information Presents” (figure 2.5), and a third containing a title page that announced, “A Party in Woodside by Judy Malloy.” This title page disappeared, and the opening screen introducing the story appeared. Readers using an Apple IIe would have seen these words laid out exactly as printed below:

UNCLE ROGER—FILE 1

A PARTY IN WOODSIDE

Woodside is a small bedroom community

South of San Francisco. Although many

of the lords of Silicon Valley Live

closer to the valley—in places like

Los Gatos or Santa Clara. There are

Some who—like tom Broadthrow—live

In Woodside. The party which Tom and hi

s wife Louise give in Woodside

Is remembered fitfully—interspersed

with dreams—by the narrator—Jenny.

The story was written and stored as a

database and is read by

searching keywords.

+ + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + +

WHEN YOU’RE READY TO BEGIN, PRESS RETUR

N

?

Pressing “return,” readers would have been taken to the list of keywords. There are exactly twenty in Version 3, including:

CHOOSE ONE KEYWORD AND TYPE IT

IN UPPER CASE

IN UPPER CASE, EXACTLY AS IT APPEARS ON

THE LIST

OR, TO QUIT, TYPE QUIT

? [BLINKING CURSOR]

This list differs from the one provided in Version 2 in that it omits “jenny’s family” and changes “refreshments” to “FOOD.” The word “suits” is also eliminated from the keyword, “MEN IN TAN.”

We may, at first, consider the move from twenty-one to twenty keywords from the standpoint of visual aesthetics: a way to create a symmetrical list with four neatly laid out columns of five keywords each, where no one line is longer than thirty-one characters. However, the list for The Blue Notebook, with its two rows of nine keywords and one row of eight, proves this theory wrong. What we can say is that all of the twenty keywords are derived from characters causing or involved in the story’s conflict. “Jenny’s family,” in comparison, provides her with comfort; its elimination from the list may be due to this reason. Or it may be due to the need to shorten the length of the keywords. Seventeen items in the list are one word of seven or fewer characters. Even the two two-word and one three-word keywords consist of eleven characters or fewer. The perceived need to save characters may also explain why Malloy omitted “suits” from “MEN IN TAN” and changed “refreshments” to “FOOD.” Malloy may have made this latter edit because there is just a lot of food in Uncle Roger, a story that unfolds at parties and restaurants. One can easily count over twenty-five references to cheese, cheese balls, salmon rolls, and sandwiches, to name a few foods referenced in the story. Finally, Malloy may have made these and other edits because she felt that as an artist, it is her right to do so (Malloy, email to Grigar, June 25, 2015).

Continuing with the work, readers would have typed in a keyword. Choosing “JENNY,” they would have received a message reading:

JENNY IS THE NARRATOR AND SHOULD BE SEAR

CHED IN COMBINATION WITH ANOTHER KEYWORD

WHAT KEYWORD DO YOU WANT TO COMBINE WITH

JENNY?

As mentioned previously, Version 3 introduced the two-query search by which readers could combine keywords and thereby follow a more specific reading path. While other keywords could be searched individually or in combination with one additional, the keyword “JENNY” required a second keyword because she serves as the story’s narrator. Choosing “JEFF” in conjunction with “JENNY” results in 16 records in which both JENNY and JEFF appear or have some sort of association with the portion of the story contained in that record.

A Party in Woodside introduces its characters and the central conflict through the conceit of a party thrown by Tom and Louise Broadthrow at their home in Woodside, two weeks after Jenny starts working for the family (Record No. 2). Tom, whom Jenny refers to as one of the “lords of Silicon Valley” (Opening), is a very dangerous man according to Dorrie, Tom’s “right hand,” whom Jenny meets at the party (Record No. 56). Tom owns BroadthrowMicro and two other businesses, one each in Massachusetts and New Hampshire, where the family also owns residences (Record No. 19). Yet, despite the Broadthrows’ wealth, Jenny is provided only a room in the garage alongside the two Mercedes the Broadthrows drive (Record No. 69). The Broadthrows have two children, eleven-year-old Caroline, whom Jenny oversees, and her teenage brother Mark, whose libido is raging (Records No. 24, 26). Rounding out the household is Puffy the cat, who injects much mischief into the plot when she licks cheese balls (Records No. 68, 37) or brushes her tail in food that partygoers carelessly eat with eerie bad karma.

During the party we hear snippets of conversations taking place among the guests: Laura, the art historian from Stanford, flirts with Jeff, the man whom Jenny met when she first arrived in the Bay Area (Record No. 21) and now desires (Records No. 67, 22, 59, 60); an unidentified man complains about the color of a rug (Record No. 23); and three men in tan suits gossip about business and lust over Louise (Records No. 27, 28). Uncle Roger’s entrance and ongoing presence at the party introduce intrigue and dark humor to a gathering of the emerging computer industry’s tasteless and bloodthirsty nouveaux riche (Record No.19). The way Jenny describes Uncle Roger, he is part buffoon (Records No. 44, 35), part trickster (Record No. 36), and very much a lecher (Records No. 11, 34, 4, 5). We also learn that he is a thief, running off with a bottle of the Broadthrows’ vodka and “bulging” pockets as he leaves the party (Record No. 44). Jenny tells us that Uncle Roger slipped upstairs and out of sight in the Broadthrow home looking presumably for the bathroom (Record No. 39). We surmise he is up to no good because he instructs Jenny not to acknowledge that they know one another (Record No. 36) and continues this ruse even when introduced to her by Tom (Record No. 37). His sleazy behavior makes his secret trip to Haiti highly suspicious (Record No. 38). During the party readers also come to understand why Jenny, a graduate of prestigious Smith College, is whiling away her time as a babysitter (Record No. 61), and we learn of the intrigue between the Tom and Jeff. Jeff’s company has just designed a “pretty hot” custom chip and needs Tom’s venture capital to take it to market (Record No. 62). If Jenny is attracted to Jeff when they meet at the airport, she is smitten by him by the end of the party (Record No. 63).

Another story Jenny recounts has to do with her relationship with David, a young man she left behind on the East Coast. Though it is not clear what happened to their relationship except that they decided not to “see each other for a while” (Record No. 61), we do know that Jenny fantasizes about him, remembering vividly their sexual encounters (Record No. 51). Jenny also talks about her family—her mother and brother living back home (Record No. 10); the death of her father when she was only seven (Record No. 11); Uncle Roger’s depraved treatment of her cousin Anne (Record No. 11); and her grandfather “Grandy,” owner of Clark and Clark, where Uncle Roger serves as vice president (Record No. 34). Another story reveals how Jenny landed the job with the Broadthrows: Jane—now married to Jack Cardin, just recruited from Massachusetts to manage BroadthrowMicro (Record No. 42)—is the sister of Jenny’s college roommate and recommended Jenny to the Broadthrow family (Record No. 49) after the previous babysitter ran off to Mexico with a lifeguard (Record No. 20). Along with Puffy the cat, who sleeps with Jenny (Record No. 45), Jane is Jenny’s only companion. She has struggles of her own: her marriage may not be working out due to Jack’s interest in other women, particularly Rose (Records No. 12, 42, 50, 52, 53). At one point, Jenny is having dinner with Jane and Jack when Jack hints at his dim view of his wife and his own enjoyment of living on the West Coast (Record No. 48).

Interspersed with these stories are Jenny’s many dreams and fantasies: Louise and Jenny piloting a boat (Records No. 30, 7); Jeff “hover[ing] over her bed” (Record No. 9); sex with Jeff on a “pullman train,” which shifts into a story of a gangster trying to get back money the imagined lovers had stolen from him (Records No. 17, 18); Jenny’s brother with a rowboat at the harbor she visits in the dream about Louise (Record No. 31); at a party with Jeff on a cruise ship, where the gangster reappears and Jenny morphs into a cigarette girl the gangster menaces (Record No. 51); a sexual interlude with Jeff in the sand at the reoccurring harbor (Record No. 70); a mysterious blue duffel bag in a house that she visits with Louise; a visit to Venice with Tom, though the man she is with “didn’t look anything like” him (Record No. 74). Jenny repeats her admission that she drank too much at the party—hinting that her memory may be impaired—when she complains of wishing for “some alka seltzer” (Record No. 72).

Though some keywords provide a series of lexias that, when combined, relay an episode of the story, the overall effect of Malloy’s composition is that the narrator’s fancies, fantasies, and dreams are realized through nonsequential storytelling that disturbs readers’ assumptions about Jenny’s experiences. It is a good example of form effectively serving the content of a literary work.

When we are ready to stop reading, we type QUIT and receive the message, “The party is over.”

Like A Party at Woodside (file 1), The Blue Notebook (file 2) is a database narrative organized around the two-keyword query. Also like file 1, this file was constructed to offer seventy-five lexias but is missing one, Record No. 62. In conversation, Malloy has indicated that this was not intended (Malloy, email to Grigar, June 25, 2015).

To read The Blue Notebook, we go through a similar process of loading the floppy disk and booting up the computer as we did for A Party in Woodside. If we want to read both files in succession, we would have to turn off the computer after reading the first file, remove the floppy disk from the drive, place the new disk representing file 2 in the drive, and turn the computer on again. The materiality of the work and the computing environment apparent in this series of activities is erased in the later, Web version of Uncle Roger. It speaks to a specific cultural moment when our relationship with media was more physically embodied and visceral.

The opening screen of The Blue Notebook offers this introduction:

The story is continued by the narrator—

Jenny.

The narrative is framed by a formal

birthday party for Tom Broadthrow

at a hotel restaurant. Within this

frame are fragmented memories—

a car trip with David

Jeff’s company in San Jose

An encounter with Uncle Roger in the

restaurant bathroom.

The story was written and stored as a

database and is read by searching

keywords. A good way to start searching

is to combine one of the main characters

at the beginning of the keyword list—

JENNY JEFF DAVID or Oncle Roger

—with one of the places or things in the list—

BLUE NOTEBOOK BATHROOM BEACH or CHI

PS. (Opening)

At this juncture readers are asked to press the return key to begin. After doing so, a series of twenty-six keywords appears in two rows of nine words and one row of eight, all in caps. To read the story, readers select and type one or two keywords. Once again, “JENNY” is the only keyword that requires a second; the rest can be searched alone:

| JENNY | DORRIE | BLUE NOTEBOOK |

| JEFF | LIZ | BATHROOM |

| DAVID | DENNIS | RESTAURANT |

| UNCLE ROGER | JACK | CHIPS |

| TOM | ROSE | BEACH |

| LOUISE | MARK | SAN JOSE |

| LINDA | PUFFY | CAFÉ |

| MEN IN TAN | FAMILY | WOODSIDE |

| SALLY | CAROLINE |

The main difference between the list of keywords for Version 3 and Version 2 is a slight change in the order of the three columns, which seems to be arbitrary since it changes the character length of the lines little and does not signify the importance of any person, place, or object in the story. More interesting, however, is the substitution of “PUFFY” and “SALLY” for the common noun “cats.” As we have seen, Puffy’s antics—licking cheese balls and putting her tail in the dip just before a partygoer eats—lighten the tension in the story and, at the same time, mete out punishment to characters we may see as deserving. In file 2 Puffy’s role is small—she appears when Caroline tells Jenny she is saving the shrimp from her lunch for the cat (Record No. 72) and when Jenny asks Dennis for his shrimp (Record No. 74)—but she is still given prominence by her appearance in the list. Sally plays the role in file 2 that Puffy had previously played in file 1. Sally appears in Jenny’s memories of David, complicating their trip to the lake when she escapes from the car. Sally is also the name of Jenny’s aunt, referenced in later versions of Terminals, leading us to wonder if this is the origin of the cat’s name. If so, then Sally the cat also serves as a link between Jenny and her family, who frequently appear in her memories.

The story picks up a few months after the party at the Broadthrow home (Record No. 23). Again, the setting is a party, this one a luncheon at a South Bay hotel restaurant in celebration of Tom Broadthrow’s birthday (Record No. 1). Jenny is seated almost alone at the far end of four tables. Most of the celebrating is taking place elsewhere, especially at the first table, where Tom sits at the head. Beyond the main action, Jenny observes and reports what she sees, but, as before, readers can’t completely trust her judgment because she admits, “The things I wrote in the blue notebook didn’t happen in exactly the way I wrote them” (Record No. 11). The use of the past tense—“wrote” and “didn’t”—suggests the stories she relates have already happened. Her thoughts and perspectives speak to what may have been and what never was.

It is Christmas season, and the restaurant is festooned with lights (Record No. 2). Uncle Roger is present, as are other characters from A Party in Woodside and a few we have not previously met. Tom, Louise, and the two Broadthrow children are all seated with a new character—Tom’s lawyer, Bob Draper. At the second table, Jack and Rose, who were kindling an affair in A Party in Woodside, are now in full flame. Rose’s perfume, which reminds Jenny of her “grandmother’s back yard on an unseasonably hot day in late spring” (Record No. 3), hint at the fecundity and sexuality the couple exudes. Jane, Jack’s wife, is noticeably absent. With Jack and Rose at the second table are Uncle Roger, ridiculously decked out for the holidays in tweed and a “tie with little pink hula girls on it,” and Dorrie (Records No. 3, 4). A third table includes three men in tan suits and another new character, Dennis, a man with a “long ponytail” who Tom has recruited from Albuquerque to solve some sort of crisis at the company (Record No. 4). Relegated to the fourth table with Jenny is Mr. Fukita, a business associate of Tom’s. In this atmosphere of merriment, abounding with balloons and presents (Record No. 5), Uncle Roger takes the role of a raunchy jester, provoking the lawyer with lewd comments about “young boys” and exclaiming about “getting laid” during his trip to Hawaii (Records No. 6, 7).

From her distant place, Jenny catches snippets of conversations: Dennis mentions a bomb to the men in tan suits (Record No. 9); Jack tells Dorrie that Rose picked out the employees’ gift for Tom (Record No. 25); Rose whispers to Jack about the hotel room they booked for the day (Record No. 31). Uncle Roger mysteriously leaves the table, and when Jenny heads to the bathroom, she finds him “lying on the couch … drinking a Bloody Mary” and waiting for her (Records No. 31, 32). They debate the circumstances of her father’s death. Uncle Roger informs Jenny that he “promised” her father he would “watch over” her and that he, not her mother, paid for her college education (Records No. 32, 33). But the real reason for this clandestine meeting is to talk about Jeff and Tom (Record No. 35) and the conflict centering on the chip Tom stole from Jeff (Record No. 55), which Uncle Roger had “knocked off in Haiti” (Record No. 57). We learn that Uncle Roger pilfered it from Tom’s study on the night of the Broadthrows’ party (Record No. 60). The fact that Jeff lost it to Tom in the first place convinces Uncle Roger that Jeff is “not a good businessman” (Record No. 60) and, so, undeserving of Jenny, who has just confessed to her uncle that she may be in love with Jeff (Record No. 59). Uncle Roger gives Jenny the chip and takes her into a bathroom stall to fill her in on the details of his piracy (Records No. 55, 56, 57, 58, 59). Jenny is eventually left splashing water from the sink onto her face and trying to figure out her life.

This lexia is pivotal. Here Jenny confronts her feelings about herself and her future, issues introduced in A Party in Woodside and fully realized as three distinct conflicts in The Blue Notebook. She states her dilemma clearly: “David wanted me to go back East with him. I was having dinner with Jeff next Monday. Uncle Roger wanted me to be a file clerk” (Record No. 70). Jenny’s memories fill in the gaps, showing us why these three issues are causing her anguish. Uncle Roger, though an admitted thief, may have been kind enough to fund her college tuition; David shows up at her doorstep after driving nonstop across the country to rekindle their relationship but still has not been truthful about the relationship with his ex-girlfriend Linda (Records No. 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69); and Jeff reciprocated Jenny’s interest with an invitation to visit his office—and with a kiss (Records No. 10, 37, 54). Alone in the bathroom contemplating her life, Jenny’s isolation is evident. When she returns to the party, she is further alienated: Tom invites her to join the family at the first table, but Louise instead chooses to include Mr. Fukita. As Jenny heads back to her end of the table, she leans over and accidentally drops the chip in front of Dennis (Record No. 73), who hands it back to her after inspecting it closely (Record No. 74).

Nested within this action are other plots and storylines, the real and surreal mixed together in an element of “magical realism” (Malloy, 4 July 2015) that keeps us guessing. Perhaps Jenny is not so unlike her uncle. We see her waking at David’s messy apartment, the “floor … covered with dirty clothes and empty food wrappers … photos of people’s picnics, weddings, and babies … tacked all over the walls (Record No. 12); discovering a photo of David’s ex-girlfriend Linda in his wallet, tearing it up, and placing it back into the wallet unnoticed (Record No. 16); losing Sally the cat in an episode that also features three women and a bucket of fish (Records No. 17, 18); remembering the shared birthday parties for her grandfather and Uncle Roger where “pointed silver hats” and party favors of “fake dog throw up” were the norm (Record No. 27); having torrid sex with David at his parents’ lake house (Records No. 47, 48, 49, 51). All these episodes ring somewhat strange, hyperbolic. Reports of Somerville being bombed by seven blimps (Record No. 50) are nothing shy of outrageous.

As in file 1, the way in which the story is evoked through keywords reflects the narrator’s fancies, fantasies, and experiences. This time, however, these are told under the conceit of retrospection and are realized through random storytelling. Files 1 and 2 share a measure of the same sketchy truthfulness, the former focused on the fuzzy nature of dreams and the latter on the nature of storytelling. In file 1 the keyword “dreams” evokes twelve records and recalls eight of Jenny’s dreams that. Four of the eight involve sexual fantasies with Jeff and the other four uncomfortable situations with Louise and Tom Broadthrow. In file 2, we find no mention of dreams. Instead Jenny uses the power of the pen and blue notebook pages to tell her tales. Shifting from dreams over which she has no control to imagination over which she has much is significant and speaks to Jenny’s evolution from girl to woman. She reveals her agency when she makes perhaps her most honest statement: “Things I wrote in the blue notebook didn’t really happen in exactly the way I wrote them” [Record No. 11]. “Blue notebook” is a keyword for twenty-one records, eighteen of which evoke conflicts involving David, Sally the cat, and chips. Only three focus on Jeff. These three, however, are the only ones in which the blue notebook appears as both keyword and object in the story. Essentially, Jenny uses the blue notebook to channel her feelings about what bothers her. It makes sense, then, that she puts away the blue notebook once and for all when Jeff discovers her writing in it at his office (Record No. 52). Thus, the writing process provides Jenny the outlet she needs to make sense of her life, especially her relationship with David, the theft of Jeff’s chip, and her feelings about Jeff. Thinking broadly about the many versions of Uncle Roger, we may wonder if Malloy herself tells an essentially inconsistent story—a story whose instability is well suited for the digital format.

The sexual content of Version 3 is graphic, in line with the previous two versions. There was no need for Malloy to tone it down, because the audience buying Uncle Roger through Art Com Catalog would have been an intellectually curious one, interested in experimental art, accustomed to uncensored work, and inclusive of some of the same people who followed her work online.17

The fifty-character line length that Malloy followed when programming Version 2 leads to unusual display in Version 3 on the Apple IIe, a popular computer that many of Malloy’s readers would have used. The Apple IIe was one of the most robust computers Apple ever produced, lasting eleven years on the market. It ran the ProDOS operating system and also offered Applesoft BASIC. By the time Malloy began work on Uncle Roger, the IIe had been available for over three years. Malloy herself owned an Apple computer but does not remember if it was an Apple II or IIe (Malloy, July 3, 2015). The standard Apple IIe made it possible to use both upper and lower case letters, which we see reflected in Version 3.3 of Uncle Roger. This version had forty-character line lengths that could be expanded to eighty.18

When looking at the lexias on the two Apple IIe computers used for this research, we see that the lines break in ways that make the story difficult to read. For example, Record No. 30 of The Blue Notebook displays as follows, with character counts added in parentheses:

| Line 1 | I ate some shrimp. It had been barbequ | (40) |

| Line 2 | ed in a | (7) |

| Line 3 | dark red sauce which tasted like those | (39) |

| Line 4 | spiced meat sticks called “slim jims” w | (40) |

| Line 5 | hich my | (7) |

| Line 6 | brother and I used take with us when we | (40) |

| Line 7 | went out | (9) |

| Line 8 | in Marblehead harbor in the old rowboat | (40) |

| Line 9 | . | (1) |

| Line 10 | “Hi, I’m Jake” | (15) |

| Line 11 | said a man in a tan suit. | (26) |

If we render the same passage with lines of up to fifty characters, as Malloy may have done for Version 2, it reads like this:

| Line 1 | I ate some shrimp. It had been barbequed in a | (46) |

| Line 2 | dark red sauce which tasted like those | (39) |

| Line 3 | spiced meat sticks called “slim jims” which my | (46) |

| Line 4 | brother and I used take with us when we went out | (49) |

| Line 5 | in Marblehead harbor in the old rowboat. | (40) |

| Line 6 | “Hi, I’m Jake” | (14) |

| Line 7 | said a man in a tan suit. | (25) |

It is important to note that the word “to” is missing from the line reading, “brother and I used [to] take with us when we went out.” Had it been included, the line would have wrapped even with the fifty-character limit.

In her Pathfinders interview Malloy explained that writing with the fifty-character restriction forced her to become a narrative poet and see her work as poetry (Malloy 2015b). Observing the varying line lengths of Uncle Roger, it is evident that Malloy thought carefully about where lines broke and how the story flowed given the line-length constraint.

While this discussion has focused, thus far, on the literary and artistic contributions of Uncle Roger as one of the first examples of a database novel and a boxed collection of hand-made art, we should also emphasize its contribution as software. Malloy began work on the Narrabase program in 1986. She envisioned the narrabase as “a fictional environment” that allows for “continually searching and retrieving narrative information” (McKeever 2014b). Uncle Roger Version 3.1, the result of these efforts, was released in 1987.

This was a watershed year for authoring software. In 1987 Bill Atkinson released HyperCard, a tool built on the concept of a stack of cards connected through a system of links. HyperCard was bundled free on Macintosh computers and was used for the production of early educational software. Digital literature, such as McDaid’s Uncle Buddy’s Phantom Funhouse (chapter 3), was made with HyperCard. At the Hypertext ’87 conference of the Association for Computing Machinery, Joyce and Bolter presented their paper “Hypertext and Creative Writing,” introducing Storyspace, a hypertext authoring system they created with John B. Smith. Joyce and Bolter also showed an early version of afternoon: a story, Joyce’s hypertext novel created with Storyspace. Like HyperCard, Storyspace made it possible for artists to produce interactive and hypertextual fiction where stories unfolded through a system of nodes and links, ostensibly modeling “how we really think” (Bolter and Joyce 1987, 43–44). Over forty works of digital literature were created with this system, two of which are highlighted in this book. Also in 1987, a team at Brown University led by Landow produced Intermedia, an authoring system built with object oriented programming that allowed for text and graphics to be linked as a “web of information” (Keep et al.). Landow wrote The Dickens Web (1990) and The In Memoriam Web (1992) using Intermedia. When Intermedia lost funding, both works were migrated to the Storyspace environment, a process undertaken by Robert Arellano (Landow), and republished by Eastgate Systems, Inc.

Even though Narrabase was in production alongside other authoring systems, and Version 3 of Uncle Roger was published commercially in the U.S. before any of the other works stemming from experiments with authoring systems (Berens 2014, 340; Grigar and Moulthrop 2015), Malloy has until recently received less attention for these accomplishments than have Landow, Bolter, Joyce, and others. However, she is well-established as an experimental artist for her artists’ books, one-off works involving such output as a hand-drawn map (Map, 1976), a quilt comprising xeroxed drawings (March at Last, 1976), a card catalog (The TV Blew Up, 1980), and a battery-operated address book (I Don’t Care if I Never Get Back, 1985). Her investigations befit the communities nurtured by the Art Com Electronic Network, a West Coast crowd decidedly different from more academic colleagues back east. Even her connection to Leonardo placed her in an orbit different from those of digital writing more widely. Uncle Roger has been exhibited since 1987 and, as we have seen, collected by the Museum of Modern Art/Franklin Furnace Artist Book Collection.

It was when Malloy shifted her mode of production and distribution, creating the third version of its name was Penelope in Storyspace and selling it via Eastgate Systems, Inc., in 1993, that she put herself squarely into the scholarly universe of early digital literature and the conversations surrounding hypertext theory and practice (see Bolter 1991; Landow 1992). Certainly, Malloy deserves to be acknowledged now for her pioneering contributions to electronic literature and computing.

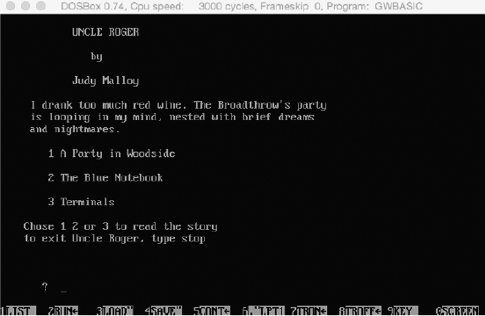

In 1988 Malloy translated the code for Applesoft BASIC into GW-BASIC in order to make a version of the Uncle Roger boxed collection for IBM-compatible computers, which some gallery managers and festival curators were using. Malloy herself had made the leap to the IBM 286 (Malloy, email to Grigar, July 3, 2015).19 This version of Uncle Roger, 4.1, was not meant to be sold but rather given away (Malloy, email to Grigar, May 25, 2015). One copy is held at Duke; another, possibly originally belonging to Loeffler (Malloy, email to Grigar, May 27, 2015), resides at the Media Archaeology Lab (MAL) at the University of Colorado Boulder. No other extant copy is on record, and Malloy has not discussed this work in the same detail as other versions.

Malloy remembers Version 4.1 having much the same content as Version 3.3, possibly with some small edits (McKeever 2014a). Unlike Version 3.3, where each file was saved on its own disk, this version featured all three files on the one floppy disk, sharing an “overarching menu” (Malloy, email to Grigar, May 25, 2015). Screenshots provided by Lori Emerson, director of MAL, only include records from A Party in Woodside and show the similarity in content between the two versions (figure 2.6). However, unlike Version 3 published as three files, Version 4 was structured like Versions 1 and 2 with all three files organized into one interface.

Figure 2.6 Introduction to Version 4.0 of Uncle Roger.

Malloy’s code for the directory clearly shows that all three files were programmed on the disk, located at lines 540, 550, and 560 of the code:

100 REM Uncle Roger PC Version

110 REM Copyright Judy Malloy 1988

350 FOR x = 1 to 10

400 SOUND 100, .01

410 SOUND 40, .01

415 SOUND 32767,1

420 NEXT x

500 FILE$ = “TITLE”

510 GOSUB 700

512 FOR x = 1 TO 10000: NEXT x

520 CLS: FILE$ = “MENU”

530 GOSUB 700

535 PRINT: INPUT ” ? “, C$

540 IF C$ = “1” THEN CHDIR “party”: CHAIN “PARTY.BAS”

550 IF C$ = “2” THEN CHDIR “blue”: CHAIN “BLUE.BAS”

560 IF C$ = “3” THEN CHDIR “terms”: CHAIN “FILE3.BAS”

565 IF C$ = “stop” THEN GOTO 900

570 IF C$ = “STOP” THEN GOTO 900

580 PRINT “You typed “; C$:PRINT “Please try again.”

585 FOR X=1 TO 10000: NEXT X: GOTO 520

690 END

700 REM FILE PRINTING SUB

710 OPEN FILE$ FOR INPUT AS #1

720 WHILE NOT EOF (1)

730 LINE INPUT #1, LINES$

740 PRINT LINES$

760 SOUND 100,.01

770 SOUND 40, .01

780 SOUND 32767,1

790 FOR A=1 to 500: NEXT A

800 WEND

810 CLOSE #1

820 PRINT

830 PRINT

840 RETURN

850 END

900 REM end

904 FOR x = 1 to 5

905 SOUND 100, .01

910 SOUND 40, .01

915 SOUND 32767,1

920 NEXT x

930 FILE$ = “title”

940 GOSUB 700

950 LOCATE 10,10: PRINT “THE END”

960 FOR x = 1 to 10000: NEXT x

970 CLS: PRINT: Locate 14,30: PRINT “c1986-1988 Judy Malloy”

975 PRINT:PRINT

980 PRINT TAB(10): PRINT “UNCLE ROGER first appeared on”

990 PRINT TAB(10): PRINT “Art Com Electronic Network (ACEN) on the WELL”

995 PRINT TAB(10): PRINT “The ACEN Datanet version of THE BLUE NOTEBOOK”

997 PRINT TAB(10): PRINT “was funded by The California Arts Council”

998 PRINT TAB(10): PRINT “and Art Matters”

1000 ENDAs mentioned, the structure of Version 4.1 recalls that of Versions 1 and 2, where multiple files shared a common menu (Malloy 2015d). We know that Malloy later used the programming from this version of Uncle Roger for Version 6, the DOSBox emulation, so we can ascertain that A Party in Woodside and The Blue Notebook functioned as databases involving two keywords, and Terminals remained a generative text with a fixed beginning and ending.

The introductory screen for A Party in Woodside 4.1 is identical to that of Version 3.3. In fact, the screenshots of the ten records provided us from Version 4.1 (Records No. 4–5, 12, 32–38) show a work exactly the same as Version 3.3, including the broken lines caused by the fifty-character restriction. If indeed Malloy made edits to this version, we cannot know exactly what they are without a copy of the floppy disk.

In 1993 Apple discontinued production of the IIe, and by the mid-1990s 5.25-inch floppy disks disappeared altogether from the market. This period also saw the introduction of browser software, a technology that made it possible to “surf” the World Wide Web to sites displaying color images, static and animated. By 1995, 16 million users worldwide were going online (“Internet Growth Statistics”). In comparison, The WELL’s usership amounted to 5,000–16,000, according to various sources.20 Recognizing what the Web had to offer to artists, Malloy created a fifth version of Uncle Roger in HTML and published it via The WELL in 1995, the first year the community opened its doors to websites (Pernick 1995). Updated in 2012 and again in 2015, this version is, according to Malloy, “the authorized text of the work” (Malloy, email to Grigar, June 25, 2015) and constitutes the version used by scholars for criticism and analysis of the work for the last twenty-two years.

The status conferred on this version, over the four previous, makes sense in light of the robustness of Web technology.21 Versions 3 and 4 were only accessible for about eight years. Approximately twenty copies of Version 3.3 were sold (Malloy, email to Grigar, June 13, 2015). We have no way of knowing how many copies of Version 4.1 Malloy produced, though we can estimate based on the number of exhibitions in which Uncle Roger was shown. Version 5, by comparison, has been readily available for over twenty years. With the exception of a new title page and introduction in 2012 (Version 5.2) and a revision to its metadata in 2015 (Version 5.3), the work remains as it was produced in 1995, unaffected by current browsers optimized for the fifth formal revision of Hypertext Markup Language, HTML5. The ubiquity and pervasiveness of the Web make Version 5 far easier to access than previous editions. Its potential audience is staggering: in 1995 less than 1 percent of the world’s population used the Internet daily; as of this writing, the number has risen to about 40 percent, or roughly 3.5 billion people (“Internet Live Stats”). There is no need to travel to Duke to read the print-out of the serial novel or to track down a vintage computer, much less find a copy of the database novel on floppy disks. Version 5 also took advantage color and images, made possible by the graphic user interface of the Web browser.22

This version also has much more space for displaying text than did its predecessors. Obviously, book pages have a fixed physical boundary, but even digital technologies such as PicoSpan constrained Malloy to a fifty-character column length with between one and eighteen lines per screen. The Apple IIe forced text to break at forty or eighty characters, with a maximum of twenty-six lines per screen. The Web browser, however, is different. One can produce a webpage with words that go on and on, allowing readers to scroll seemingly forever. The only limitations center on design considerations, server capacity, and readers’ patience. The Web’s linking feature also condenses the actions required to access lexias into a simple click on a word in the navigational menu. Versions 3 and 4 of Uncle Roger required readers to query the system with a keyword, then wait for the next screen, possibly add a second keyword, then wait for the screen containing the first lexia associated with the relevant keywords. Cutting the number of steps between reader and text down to one click makes for a more immediate reading experience.

Version 5, like all versions besides 3.3, unites the three files into a single interface with a shared menu (figure 2.7). Different, however, from all other versions is the use of color and graphical elements for navigation. The layout, divided into two parts, offers a menu on the left of the screen containing an artist’s statement, background on the story, and access to a BASIC version created for the DOSBox emulator. Arranged vertically in the middle of the screen, in order from file 1 to file 3, we find A Party in Woodside, The Blue Notebook, and Terminals represented by both a graphic image and text. Visitors to the website simply click on one or the other to access the story.

Figure 2.7 Interface for Uncle Roger, Version 5.

Clicking on file 1 of A Party in Woodside takes readers to its opening page, where they encounter a list of fifteen hyperlinked words and an image of a wine glass filled with red wine. This image represents Jenny’s words, “I drank too much red wine,” encountered in the previous versions of the story. Each word in the list, if selected, takes readers to a screen that features a lexia with an accompanying image. Selecting “Louise” from the list of words on the opening page, for example, takes readers to this lexia:

When the party began, the plastic cover

was removed from the white couch.

Mrs Broadthrow was wearing a lime green silk suit

that I had just picked up for her at the cleaners.

Her blouse was white silk with a plunging neckline. Gold earrings

framed her finely chiseled face.

Her name is Louise.

To the left of the lexia is again the image of a wine glass. At the bottom of that lexia we find the navigational menu of twenty-one words, with four of these, including “Louise,” hyperlinked. Choosing “Louise” from that list or clicking on the image of the wineglass takes readers to a new lexia pertaining to Louise. The two choices for navigating through the story—the hyperlinked words at the bottom of the screen and the image—recall the two-keyword search combination of the database narrative that constitutes both Versions 3 and 4.

In Version 5 Malloy brings back all twenty-one keywords from Version 3.3 as well as one omitted—“family.” Five keywords listed in Version 3.3’s opening screen are excluded from Version 5’s—“Miss Gorgel,” “Mark,” “Caroline,” “David,” and “Rose”—but, thanks to the limitless space Malloy has to work with, are listed in the navigational menu at the bottom of the screen.

The structure of The Blue Notebook differs from that of A Party in Woodside. Malloy uses only images for navigation—gone are the textual links. Though Malloy had used graphic icons previously for The Woodpile, the artwork she produced as a card catalog in 1981 (McKeever 2014b), the addition of images to Uncle Roger in the Web version suggests a major change. Until this time the work had been expressed almost exclusively in words, with just one ASCII graphic found in its introductory screens. The inclusion of graphic images and use of graphical elements as hyperlinks were both innovative because early Web pages tended to comprise primarily text. The first Web pages, published in 1991, were “exclusively textual” because of speed constraints imposed by dial-up modems. By the mid-1990s, graphical elements had made their way into Web design (Kelly 2013), but Malloy’s application of them was unusual for 1995.

Another change in the Web version involves the way readers can search the work. Whereas before they could search one to two keywords for records, now readers had three graphical choices for navigating the story. As Malloy writes: