Figure 5.1 Bill Bly giving his traversal at the Maryland Institute for Technology in the Humanities, University of Maryland College Park, on February 2014 for the Pathfinders project.

Figure 5.1 Bill Bly giving his traversal at the Maryland Institute for Technology in the Humanities, University of Maryland College Park, on February 2014 for the Pathfinders project.

“If this document is authentic.” This is the five-word phrase that came to Bill Bly, prompting him to write We Descend. The implications of the phrase led Bly to wonder about what a document is and what it means for one to be authentic. It made him curious about the people who determine the authenticity of documents: What are they like? What are their struggles? How do they come by their authority to determine a document’s authenticity (Bly 2015b)? These questions shaped his experiment in We Descend: hypertext as an archive of documents. The result of this exploration into narrative form is a compilation spanning generations. Its 598 nodes of text, or lexias, connected by 864 links, “pertain” to a scribe named Egderus Scriptor.

Egderus’s collection is diverse. There are ruminations, bits of poetry, quotes, testimonies, and stories from his time. There are also earlier, pre- and postapocalyptic writings from a group identified only as the Ancients. Commenting is the Scholar, who discovers Egderus’s texts and is disturbed by the truths both suggested and overturned in their historical account. All of Egderus’s and the Scholar’s material is itself collected by an unnamed Annotator/Compiler/Selector/Redactor (“And a last (fore)word”). Finally Bly intercedes as Curator of the work, rendering the archives into hypertext along with a foreword, afterword, directions for reading (“Title Page”). The archives cover four bands of time: those of the Ancients, Egderus, the Scholar, and the Annotator. Bly’s intervention introduces a fifth period—the present. Because the work reflects many voices relating disparate texts over a long stretch of time, readers of We Descend are challenged to discern who is speaking and what the exact context is in the narrative, but this approach reflects the very issue scholars face when working with ancient texts: truth and authenticity are impacted by time.

Bly’s studies of ancient Greek inform We Descend. Released in 1997, its roots lie in archival research of ancient texts. It follows archival efforts of the mid-1990s, the most notable being the Perseus Project. Begun in 1987, Perseus was first published on CD in the early 1990s and to the Web in 1995. This rich archive of ancient Greek and later Roman texts was groundbreaking in scope and today continues to provide scholars with unparalleled access to ancient Western culture and tools for textual study. A word search of Homer’s Odyssey that, in 1993, had taken this author months of labor by hand, was reduced to fifteen minutes using a computer with access to Perseus, Greek Keys—the software classicists used to produce ancient Greek type with diacritical marks—and the word-search program Pandora (Grigar and Corwin, 1998). Among Bly’s personal possessions donated to the Electronic Literature Lab at Washington State University Vancouver were copies of a Perseus CD and Greek Keys.

Like the Perseus Project, We Descend is an archive of texts augmented by scholarly notation. But We Descend is fiction, and it experiments with the potential of hypertext by structuring multiple, nested narratives that unfold linearly, revealing truths in measured moments of myth, maxim, and testimonial. To read We Descend as a hypertext novel is to assume it will deliver something it is not intended to. For it is not precisely a nonsequential work of fiction, but rather a compilation of interconnected archives relaying bits of information as incompletely as one would expect of an ancient text.1

We Descend has been the subject of reviews and essays since soon after its publication. Susana Pajares Tosca’s 1998 review provides a good introduction to the work and its approach. Jan Van Looy’s 2002 review for Dichtung Digital argues that We Descend is so linear as to constitute a hypertext “novella.” The most recent discussion of the work, in Astrid Ensslin’s Canonizing Hypertext: Explorations and Constructions, focuses on We Descend’s form as a mystery and crime novel, its linear structure, and its narrative strategy (Ensslin 2007, 86–87).

Both Tosca’s and Van Looy’s reviews were produced at a time when computers reading floppy disks and CDs were still readily available. Even in 2007 Ensslin could access the technology she needed for her research. By 2008, however, Apple began to phase out CD drives in its computers (Lowensohn 2013), and by 2009 CDs were falling into disuse (“How vinyl record sales stack up,” 2009). Today it has become very difficult to find a computer that can read them.

To write this chapter, this author used the CD version of We Descend, Volume 1 (produced with Storyspace 2.0 in 2006) in MacOS 10.3.9 on her vintage iMac G4—the model known as “sunflower,” manufactured in 2002–2004. Others wishing to read the work would likewise need a vintage computer. As with Uncle Buddy’s Phantom Funhouse (chapter 3), it is ironic that a project exploring archival work and the authenticity of ancient documents should itself become obsolete in less than twenty years, and so in need of preservation.

In that regard we serve as a sixth round of scholars in an already long line of archivists examining and commenting upon the documents found in We Descend. But, without access, the archive and exploration Bly made into its form are both lost. This chapter, therefore, takes advantage of a specialized preservation laboratory in order to provide this in-depth look at We Descend as a work that experiments with the archive as narrative form while this type of access is still available to us.

Volume 1, 1997, on floppy disk (and CD, after 2000), with Storyspace 1.0, sold and distributed by Eastgate Systems, Inc., $24.95; for Mac OS 9 and earlier.

Volume 1, 1998, on floppy disk, with Storyspace 1.0, sold and distributed by Eastgate Systems, Inc., $24.95; for Windows 95, up to Windows XP.

Volume 1 “WeDescend_30node,” 1998, with Storyspace 1.0; produced for readings and performances.

Volume 1 “Excerpt,” 1998, HTML version, in the Gallery at Word Circuits; based on “WeDescend_30node,” http://www.wordcircuits.com/gallery/descend/Cover.htm.

Volume 1 “Excerpt,” 1998, WordPress version, at wedescend.com.

Volume 1, 2006, on CD, with Storyspace 2.0, sold and distributed by Eastgate Systems, Inc., $24.95; for Mac OSX 10.2 and later).

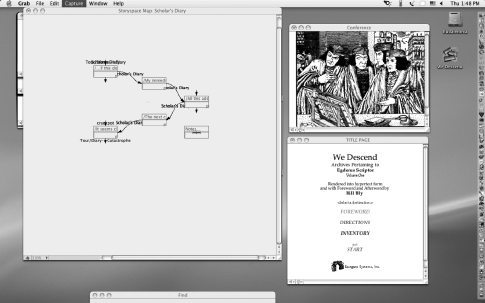

Figure 5.2 The nodes and links of Bill Bly’s We Descend.

We Descend

Archives Pertaining to

Egderus Scriptor

Volume One

Rendered into Hypertext form

And with Foreword and Afterword by

Bill Bly

<Select a Destination>

Foreword

Directions

Inventory

just

Start

Bly’s work begins with a title page, which gives way to an epigraph from Margaret Atwood’s poem, “Two Miles Away”:

Night rises from their bodies

and spreads over the hills;

musty; smelling of thunder;

the air around their heads

thickens with ancestors.

Alluding to the darkness and weightiness of the past, the poem presents readers with an ominous warning. Not unlike the inscription found at the entrance of Dante’s Hell, this note speaks of the dangers ahead and of the atmosphere readers are about to encounter.

The default path gives a tour of the writings in the archive. Readers enter the first section when they click on the box containing the lexia (see figure 5.2). This introduces the Scholar, who is inspecting Egderus’s archive. The nineteen lexias comprising the archive carry the foreboding tone and mood set by Atwood’s poem and hint at a major environmental disaster, where storms “last all night” (“Storms and haze”) and “the air is heavy and foul” (“The days are worse”). The ancient narrator describes a “dwindl[ing]” population. Then, the fourth lexia shifts the authorial voice: “If this document is authentic, then a complete reappraisal will be necessary.” We surmise that here the Scholar has taken over, with his assessment of an older “document” concerning the disaster.

Clicking on the fourth lexia takes us back to the ancient narrator, who laments the dire situation in which he finds himself and wishes to return to “history, music, words that mean something, and say them” (“Nobody knew what hit”). The voice shifts back again to the Scholar, who struggles with what to do with this writing that goes beyond ostensibly accepted facts like “lists, inventories, and fragments … of poetry.” We learn that the ancient text was copied by a scribe who served as “director” of the “Remnant,” a class of “slaves” who “no longer contribute to society, and who would be better off dead, or at least out of the way” (“So, it might be argued”). The Remnants are scraps of humanity, like the fragments of text he holds in his hand. At this point, we learn that the scribe is Egderus, “one of the first scribes of the Goliadic Age,” whose existence has been documented in a list, “dated” and “signed,” and, so, is accepted as truth.

Egderus’s document, however, is fraught with problems, for it contains information not yet accepted by the Scholar’s culture. Additionally, because it is a “copy made very recently” and not an “original,” its veracity is in doubt. Also puzzling is that the document treats the words of the Remnant like wisdom of the Ancients (“At first I thought”). The Scholar asks himself if he should come forward and risk his reputation or labor silently behind the scenes building his case to prove the writing’s authenticity. The narrator’s fragmented thoughts, where arguments are made and rejected with each click of the mouse, reflect inner conflict. A quote from Leviticus 26:36—“And as for those that are left, I will send faintness into their hearts … .”—warning against disobedience to God underscores the Scholar’s dilemma. Clicking on this lexia takes readers back to the ancient document copied by Egderus. In this text, the speaker contemplates the nature of history and ponders what is at stake with the loss of his heritage in the face of his world’s demise:

History used to be a question of finding out, not remembering. You read books, you took courses, you watched shows with actors in period costumes. Occasionally after dousing yourself with names and dates, you entered the realm of the historian’s secret delight: you got a feel for a time and place long ago and far away. That’s all over. Every time is gone now, every place infinitely remote. Without the past, what’s the present? In a shapeless present, where’s the future? (“Who cares what”; emphasis in original)

The use of the word “history” is ironic. Derived from the Greek historia, it refers to research or investigation. Greek philosophers and historians viewed historia as a rigorous examination of information, learning by inquiry, narrative involving the past from which we gain insight of the present and future. Those of us familiar with Herodotus’s Persian Wars or William of Poitiers’s History of William the Conqueror know that today’s historians have more respect for evidence than did their ancient and medieval predecessors,3 whose duty was as much to raise philosophical and religious questions as it was to align information to reality. Exactness does not necessarily equate to truth, as the passage suggests. Truth, or alethe in Greek, literally means “not forgetting” and carries with it the idea that things that are true are really just those things we need to remember. Even with access to evidence for the purpose of remembering, how does one create a cultural narrative not built on lies when one cannot question the veracity of that evidence? Herein lies the problem, and it is the problem that leads to the ancient author’s (and, by association, the Scholar’s) rejection of history—“the mess and redundance of life made understandable.” Better, the speaker muses, is to call oneself a “musician” (“Nobody knew what hit”). Clicking on this lexia ends the ancient text abruptly. The story shifts to the phrase, “Here Beginneth The,” and we are taken to “the Testament of Egderus, 9th Superius Frater of Mountain House, in the 50th season of his tenure,” the second section of the archives.

The Testament relates a mystery unfolding over numerous nested stories. At the center lie the death of Gig, the Phylax of Mountain House, and the examination of the Historian, separate events that seem to be intertwined. The Testament also hints at Egderus’s rise to a position of authority. Already an archivist, he becomes secretary to the Superius Frater, and, along with other young scribes of Mountain House, is harassed by Gig. One day Gig finds Egderus, who is lame, alone and attempts to kill him with his axe. Waking up later in the infirmary, surprised to be alive, Egderus tells the patient in the bed next to him about the incident. The next day Gig disappears; later his decapitated body is found.

A new phylax named Robenc takes Gig’s place and decides to solve the mystery of his death. Because Egderus was the last person to see Gig alive, Robenc questions him. The Primus Frater—a man also known as the Good Doctor, who works under the supervision of the Superius Frater—becomes angry when he learns that Egderus confessed to seeing Gig before he disappeared. He punishes Egderus by forcing the young man to copy “more than two dozen books from the library” before the “Year’s End.” Egderus refers to these books as a “hodgepodge of scribblings”: “chronicles of the Old Kings, several Scriptures, the Songs, and a collection of miscellaneous writing—annals of Mountain House, receipts and accounts, inventories, even recipes from the kitchen” (“It was not my habit”).

More punishments are handed down. Egderus is forced to join the Good Doctor at the older man’s new station away from Mountain House. Before Egderus’s journey, the Superius Frater gives him a piece of advice: “Believe what seems to your heart to be true, but be prepared to abandon that truth the instant it plays you false” (“My son I must”). And then it is time to leave: “the tree closed the Gate out of sight, and the descent began.” The drive to his new home gives Egderus time to contemplate his situation. He realizes that the Superius Frater is not omnipotent and lacks power over the Good Doctor. Egderus concludes that, in fact, the Good Doctor more than likely was sent to Mountain House to keep an eye on the Superius Frater. Egderus also determines that the Superius Frater was sent to Mountain House against his will, owing perhaps to some scandal. The exile wishes to learn “where such power was generated” (“Finally: who was this”).

After another abrupt shift in time, Egderus has arrived at his new home and now serves as the Good Doctor’s secretary. The Good Doctor has been designated the Prior to the Chief Inquirer, a lofty position that allows him much freedom with his examinations. This position resembles that of a Grand Inquisitor, whose job is to eliminate heresy, presumably through torture. In We Descend, heresy is specifically historical heresy: scribes are expected to write the past as it should have been, not as it was (“The Good Doctor had”). The principle heresy is the belief that the Ancients were not gods but human beings (Bly, email to Grigar, August 21, 2015). Egderus’s job is to write down the information the Good Doctor gleans from his “clients”—heretics subjected to examination (“What I was cataloging”). These sessions seldom go well for the client, whose examiners seem to enjoy the process of prying out “realizations.” Egderus “loathe[s]” the examiners, who love the torture by which they extract truth rather truth itself. Over time, Egderus begins to see both the scriptors and examiners as hypocrites (“My contact”).

Years go by, and Egderus develops a romantic attraction to the Historian, a man the Good Doctor plans to examine for heresy. Sent out of the Good Doctor’s office one day, Egderus finds Robenc waiting for him. Robenc pumps Egderus for information about the identity of the Good Doctor’s client. Robenc, we learn, is no longer just a Phylax but has “ascended” to the rank of Praetor, Governor of the Bodyguard, protector of everyone, including Egderus (“Don’t be angry”). The Good Doctor is not happy to see Robenc but takes the man into his office to talk anyway. From a hiding place in a cabinet, Egderus listens in (“Even as I first crawled”). Robenc tells the Good Doctor that the Historian is a “friend of the Golias,” the highest-ranking leader, and wants the Historian freed. The Good Doctor refuses for lack of proof (“It should be”). When the Historian is mentioned, Egderus “jerk[s] upright,” his actions alerting the Good Doctor to his eavesdropping (“At the sound of my”). After the meeting the Good Doctor beats Egderus so severely that he must visit the infirmary for care.

The turning point in Egderus’s life comes when he decides to save the Historian. He realizes that he will need to bring down the Good Doctor (“The choice”). Egderus knows the Good Doctor will finish his examination before Robenc can intercede on the Historian’s behalf, but Egderus also believes the Historian will not be tortured until Egderus returns from the infirmary. He is right. The Good Doctor needs Egderus to return in order to finish his job. While Egderus is in care Robenc visits a comrade, Aric, in the infirmary. This coincidence gives Robenc the opportunity to question Egderus about the Historian. Together, Aric and Egderus plot to save the man by having Egderus turn over to documents about the Historian’s examination.

From this scene, readers enter yet another story, about Gig. Aric tells Egderus that, at one time, he and Gig had found the body of a young soldier “by the spring.” His death was like Gig’s. Other bodies of young soldiers had also been found by the spring. Gig, it seems, was troubled after he found the first (“There had always been”). Blame for these violent deaths was assigned to the strange rocks that form the landscape of the area. Gig and Aric decided to investigate. On one of their journeys to the rocks, Gig and Aric spied the Good Doctor coming down the road, far from where others generally walked. They played a trick on the Good Doctor to scare him, but he disappeared. With some investigating, Aric and Gig discovered his potential place of escape—a room within the rocks. But instead of seeing the Good Doctor, Gig encountered something that changed him into the man who chased Egderus with the axe, and which may be the cause of his own death by dismemberment. We never learn what that something is.

Another shift occurs, and readers are taken to a story consisting of twenty-one lexias about an encounter between the Superius Frater and Robenc (“I had withdrawn”). We can tell from the conversation that the meeting takes place at the same time as Egderus and Aric’s plot to help the Historian; the meeting provides another perspective about the Golias’s motives for finding the Historian. Evidence suggests that the Historian was last seen with the Good Doctor at the Office of Inquiry. Robenc asks the Superius Frater help locate the Historian.

The story involving the mystery of Gig and the Historian ends abruptly (“Well, the investigation”). We never learn who killed the former Phylax or why the Golias was searching for and trying to save the Historian. We may not recognize it at first, but, based on the gloss—that is, the hyperlinked information that serves as the Annotator’s commentary of the text—we come to understand that the Abbot is another name for the Superius Frater, under whom Egderus served when he first lived at Mountain House. This passage hints at why Egderus himself eventually ascends to the position of Superius Frater: he has the temerity to tell Robenc that the Good Doctor held the Historian in custody and was examining the man (“The very same. he”). He is willing to question authority and risk punishment to speak the truth—brave enough to be authentic to himself when others rely on him to be otherwise.

After yet another abrupt shift, readers arrive at the “articles of faith—to lose, to suffer, to learn”:

The more you appear the winner—the more humiliating will be your defeat. From this you learn. The more you have been broken by suffering—that much more suffering will be heaped upon you. From this you learn.

The more experience you have, the greater your mastery, the subtler your thinking the more abundant your knowledge—that much the more naïve, clumsy, stupid, and ignorant you will be shown to be. From this you learn.

For the hope of winning means everything until it has been achieved: the prize bestowed is no longer prized. Having won means nothing: A new challenge, a new test, must forever be proposed. This is vanity.

History … myth … the remnant, preserved for a later generation, not as an exemplar, but as an albatross. (“To lose, to suffer”)

Readers cannot be sure who is talking at this point; however, since we are still within the Testament of Egderus, we can assume he is speaking. We learn later that the first three paragraphs are indeed Egderus, but the last is the Scholar. Over the next eleven lexias, we learn that the world had been destroyed and that the documents Egderus has been copying reflect a worldview that the Golias envisioned after the dust settled and rebuilding began. In essence, the Golias controls the present and the future through the historical accounts of the scribes. Section two ends with Job 5:23: “For you shall be in league with the stones of the field, and the beasts of the field shall be at peace with you.” The context of this passage—Eliphaz’s reminder to Job that the truly good are never forgotten by God—further emphasizes Egderus’s strength of character as the source of his eventual rise to authority.

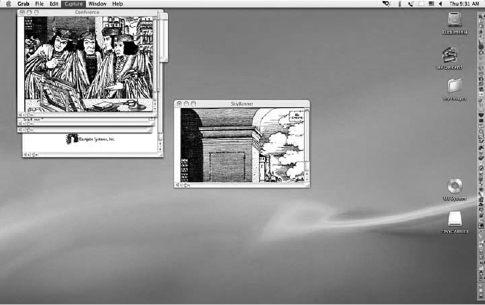

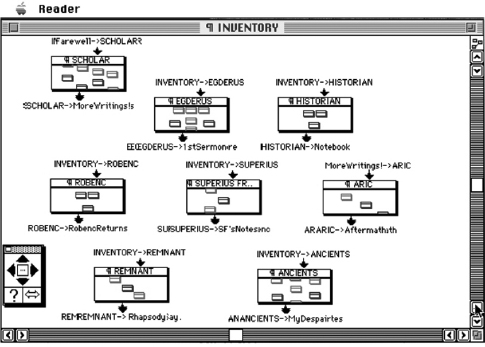

Via the default path, readers arrive at the third section of We Descend, “Sermon at the First Gathering.” There is some question about the context for this talk. As mentioned previously, we are not sure exactly what this information entails or why it is dangerous; we have to take the speaker at his word. Though it was supposedly given at a specific event, the content itself is highly provocative (“Sermon at the first”). It is, in fact, a pointed criticism of those who are “jealous and spiteful,” “boastful and self-serving,” and “wrong” (“They are jealous and”). When we click on the final lexia of the sequence, we evoke an image of four men examining a book. The title of this image, “Conference,” takes us back to the beginning of the archives, where the Scholar struggles with how to present to the conference the controversial information he has discovered. Clicking on this image takes us back to the title page. This time there is no “start” link. We can only access the foreword, directions, and inventory. In the inventory, Bly as Curator has collected all of the commentary the Annotator provides about the eight major authors of the writings: Scholar, Egderus, Superius Frater, Historian, Robenc, Aric, Remnant, and Ancients. This material challenges the authenticity of the archives we have just read. Writings ascribed to the Remnants, for example, may have been written by Egderus or the Good Doctor; the story of Robenc as a young man may have been a “hoax” (“Young Robenc”). Readers can sustain belief in the archives because the Annotator endows it with some level of authenticity by arbitrating which information is correct. However, because curation (Cairns 2013) and translation (Raffel 1989, 50) are authorial acts, Bly ascends to a status higher than Egderus, the Scholar, and the Annotator who precede him.

It is important to reiterate at this juncture that the version of We Descend used for this chapter is the 2006 version produced with Storyspace 2.0, accessed via a Macintosh computer dating from 2002 to 2004. This author also read the work using the default path as she did when she first bought her copy in the late 1990s. Anyone studying this work on this computer using this method would encounter functionality specific to it, functionality that affects the reading experience.

For example, the archives present a wide array of textual data organized into three main sections and seven sub-groupings. The default path reveals pieces of the archive bit by bit in linear fashion. Each node remains fixed on the computer desktop as another node appears on top of it, until there is no visible way to return to the beginning. Selecting the title in the bookplate opens an annotation on that particular writing, and clicking the navigation tool take readers to the beginning of the writing itself, but locating any single lexia of the story amid the dense stack is more difficult. In this way the work reflects the messy detritus of existence and recalls the need of archeologists to dig deep—descending, so to speak—to find truth and meaning amid layers of remains (figure 5.3).

Figure 5.3 Layers of lexias.

But, as Bly reports, he did not intend for the lexias to pile up as they do, reinforcing the essential point that the medium of interaction alters the functionality of a work. It was Bly’s understanding that readers using Storyspace would be able to opt out of keeping windows open by setting a preference in the software. But this option is not available on the copy of We Descend used for this chapter (Bly, email to Grigar, August 20, 2015).4 Whether the effect of 108 lexias stacked atop one another on a computer screen is intentional or a byproduct of the system’s programming, we are provoked to ask how we can make sense of our past when the information comprising our present is nearly impossible to sift. The same challenge faces us now, with so much information piled up in our inboxes and available on the World Wide Web.

The archives are introduced by the Epigraph, which sets the tone and mood for the entire compilation. Section one is made up of alternating prose and verse, resembling a prosimetrum.5 It includes five groupings of nineteen lexias introducing the Scholar. Section two consists of eighty-three lexias from Egderus’s Testament presenting the mystery of Gig’s death, the Historian’s examination, and the story of Egderus’s rise to a position of authority at Mountain House. Section three’s five lexias offer a sermon by an older and wiser Egderus.

| Section 1: Scholar’s commentary on Ancients’ texts, as copied and archived by Egderus | ||

| Narrator | Lexias | Approach |

| Ancients, preserved by Egderus | Storms and hazeThe days are worseI cannot bear this | Poetry, lament |

| The Scholar | If this document is authenticMy immediate problemAll this adds upThe next conferenceIt seems clear | Scholarly commentary |

| Ancients, preserved by Egderus | CatastropheI must get away from | Poetry, lament |

| The Scholar | The document purportsSo it might be arguedAnd in a senseAt first I thoughtIf so, who were they | Scholarly commentary |

| Ancients, preserved by Egderus | LeviticusWho care whatNobody knew what hitKids never know | Biblical quotation, lament |

| Section 2: Egderus’s Testament: the story of Egderus’s rise to power at Mountain House | ||

| Narrator | Lexias | Approach |

| Egderus | “Here beginneth the” | Testimony involving nested stories by Egderus and others about Gig’s murder and the Historian’s examination by the Office of Inquiry |

| + 82 lexias | ||

| Section 3: Egderus’s Sermon | ||

| Narrator | Lexias | Approach |

| Egderus | Sermon at the first gatheringOne of these strategiesBut then one dayBut we are differentThey are jealous and | Sermon |

At any juncture readers can reveal additional information provided by the Annotator by holding down the option and command keys (OPT-CMD), or the so-called Tinker and Bell keys.2 Readers familiar with electronic literature produced with Storyspace in the 1990s would have known that they could “see words that yield” (Joyce 1995) by using this keyboard command. As we have seen in previous chapters, electronic narratives fundamentally resist textual wholeness. They may be reduced to a single narrative relayed through nonsequential writing, as in our recorded Traversals, but only if one is prepared to omit or pass over parts of the text. We Descend takes this tendency even further than Malloy’s Uncle Roger, McDaid’s Funhouse, and Jackson’s Patchwork Girl. As its structure shows, its function as a narrative is almost incidental. The work is rather a compilation of archival writings held together by hypertextual links of which narrative reflects but one type of writing.

Considering that the work represents generations of historical documents about Egderus, there are understandably large gaps in time. Within the groupings of documents and in the stories reflected in those documents, time does not necessarily unfold chronologically. As contemporary readers accessing the archive, we encounter first a poet of our own time, Margaret Atwood, in the epigraph. In the next lexia, “Storm and haze,” readers are taken to a very ancient period representing the first grouping of texts in the section. As mentioned, it is difficult to discern who is talking or what the context is. Readers get an inkling of identity and situation only when they reach the second grouping: someone from a more recent past is reading those texts and commenting on them.

Using the option and command keys at this juncture of the story, readers discover yet another time period, that of the Annotator, who comes from a fourth past but is closer to us temporally than are the other two voices. The mix of pasts suggests the muddle scholars experience when trying to reconstruct textual fragments. Think of how one might tease out ninth-century Islamic commentaries from Aristotle’s treatises. This is the gist of what Bly demonstrates with his archives.

Section two, the Testament, offers four main stories, three of which occur within the physical space Egderus inhabits—Egderus’s youth at Mountain House and eventual exile, Egderus’s work and espionage at the Office of Inquiry, the plot at the infirmary. Whereas Section one is recounted in first person, Section two is told in third person. This distances readers from the text and calls into question who has written or copied this section and who acts as its narrator. If truth is indeed those things we remember, then truth is personal and specific and so contingent upon our willingness to share it with others. From this perspective, third-person narrative—a story remembered by another and relayed to us—can never be proven true. We did not experience the situation firsthand, so we cannot know if it really happened. Lack of embodied knowledge makes others’ claims suspicious. We can only trust the ethics of the storyteller. Thus Bly sets his readers up for a state of disbelief at the outset of Egderus’s Testament. This is why the Annotator’s commentary becomes so important for imbuing the archives with some veracity and why Bly, as Curator and Translator, ultimately emerges as the major “scriptor” of the work.

To reiterate this section for the purpose of highlighting the structure of We Descend: The first story we encounter in this section involves Egderus as a youth living at Mountain House and serving as secretary to the Superius Frater. He is severely injured by Gig and learns, later, that Gig has been murdered. He is subsequently interviewed by Robenc who has taken Gig’s place and, then, punished by a man called the Good Doctor, who is angry with Egderus for revealing information to Robenc. The second story picks up after Egderus is forced to leave Mountain House and become the Good Doctor’s scriptor at the Office of Inquiry. Egderus witnesses examinations that involve torture and is moved to action when he falls in love with one of the men, a Historian, that the Good Doctor calls to his office. When Egderus is caught spying on the Good Doctor’s conversation with Robenc, the Good Doctor beats him so severely that Egderus needs medical attention. The third story begins in the infirmary where Egderus is taken. He meets Robenc, who has moved up in rank, again. Robenc pumps Egderus for information about the Historian before leaving the young man with Robenc’s friend, Aric, who is lying in the next bed. Together they plot against the Good Doctor. Within this story is nested Aric’s about Gig’s transformation from a respected watchman to the crazed monster he becomes. This story also involves the Good Doctor. The final story shifts from Egderus’s space to that of the Abbot’s office. It also takes place within the same time frame as the third story. In this story, after leaving Egderus at the Infirmary, Robenc visits the Superius Frater, who is also the Abbot, and recounts the Golias’s search for the Historian. Egderus’s presence is evoked when the men recognize his contribution to identifying the Historian as the client in the Good Doctor’s office.

| Stories | Location | Characters in the Story |

| #1: Gig’s attempt to injure Egderus and Gig’s death | Mountain House | Egderus, Superius Frater, Gig, Brother Anders, Primus Frater (the Good Doctor), Robenc |

| #2: Historian’s examination | Office of Inquiry | Egderus, the Good Doctor, Historian, Robenc |

| #3A: Robenc’s surprise appearance | infirmary | Egderus, Robenc |

| #3B: Aric’s story about Gig | Mountain House | Aric, Gig, the Good Doctor |

| #3C: The plot to ruin the Good Doctor and save the Historian | infirmary | Egderus, Aric |

| #4: The Golias’s interest in the Historian and Egderus’s identification of the Historian to Robenc | Abbot’s office (possibly while Egderus lies in the infirmary) | The Abbot and Robenc (Egderus is mentioned) |

Section two ends abruptly without resolving the mystery. Following the default path, readers never learn who killed Gig, why the Historian ended up at the Good Doctor’s office, why the Golias was so intent on finding the Historian, or even what happened to the Historian. This information is as lost to us as any number of stories we don’t know from the past. What is clear is that all relate directly to Egderus, tracing his life from boyhood to young manhood and hinting at why the archives “pertain” to him. Each story is recounted in linear form, but because they move in time (as with Egderus in the Infirmary) and space (as with the Abbot and Robenc in the Abbot’s office), the overall effect is confusion—the confusion one would feel reading a compilation of archives. Egderus, whose presence is strong throughout, holds the archives together.

Section three moves on to sermons by Egderus. His rank is higher than it had been in the previous section, when he served as Secretary and then Scribe, but lower than the one he seems to hold in the first section, when he comes across as a learned scholar analyzing the provenance of an ancient text.

We Descend unfolds largely as a linear text with hypertext links to commentary. Navigation via the default path occurs by clicking on the lexia in the structure map or on the arrow-shaped tool on the navigation palette. Some lexias allow readers to move nonlinearly to other lexias. For example, “Ah, but my productive,” a lexia that introduces the encounter between Robenc and the Abbot in the fourth story of Section two, includes the phrase “Yours had barely started,” which links back to the lexia, “When Robenc was a young.” When readers arrive at this lexia, there is no hyperlink to another. Bly and others working with Storyspace used these so-called allusion links “to echo some other story but not totally interrupt [the] reader’s progress” (Bly, August 21, 2015). Readers reach a dead end and must go back to the previous lexia to continue.

Not surprisingly, criticism of We Descend has focused on it as a “static hypertext” (Van Looy 2002). Why then did Bly produce the work as a hypertext, and why as a Storyspace hypertext? To be certain, Bly anticipated some level of debate about his approach when he wrote in the foreword that:

Someday, when the gulf allegedly fixed between “linear” writing and hypertext has either been bridged or is at last shown never to have existed at all, essays like this one will be regarded as awkward and unnecessary, however quaint and/or evocative they may be. … That day is not yet. Everyone who proffers a hypertext to the work must still provide an explication of the apparatus. This foreword is no exception.6

Anyone reading this passage is warned that the mix of linear and nonsequential storytelling is intentional.

One of Van Looy’s criticisms focuses precisely on We Descend’s approach to hypertextuality. He recognizes the work’s “multilinear structure with a three-dimensional time frame and the possibility of inline thematic or associative linking” but complains that “there is only one … way of reading We Descend and that is the default way, following the path links.” In other words, We Descend is a “static hypertext” (Van Looy, 2002).

True, if one expects a fragmented, decentered novel possessing multiple paths, We Descend may disappoint. But that’s not what We Descend is, nor what Bly intended it to be. It is, rather, an experiment in archival writing, in which documents reflecting different historical times are held together with a technological mechanism native to late-twentieth-century scribal culture. Understood in these terms, the work’s approach to hypertext makes sense. This potential for apparently linear unfolding also was present in hypertext from the very beginning. In the preface to afternoon, Joyce similarly anticipates a reader who will “rid[e] a wave of returns”—that is, move through a predetermined path—by hitting the return key (1990), meaning that he envisioned readers who would attempt to read a hypertext narrative in a linear fashion, not realizing the potential for the text’s nonsequential feature. Victory Garden contains “something like 37 distinct pathways … that require the reader to do nothing more than press the Return key after reading one of its lexias” (Moulthrop 2011). Furthermore, while We Descend happens to contain, along with a lot of other types of writing, a murder mystery, one cannot categorize the complete work as a “crime novel,” as Susana Pajares Tosca does (1998, 87).

To see how invidious the comparison to a novel really is, consider We Descend’s predecessor, the Perseus Project, now called the Perseus Digital Library. There, readers can, for instance, find two stories about the mythological Medea: Euripides’s, dating 431 BCE, and Seneca’s written, roughly, 400 years later. The two texts differ—Euripides’s Medea acts immoderately because she is wronged, while Seneca’s enjoys being cruel—but both tell the story of a fictional character and are linked in an archive about her. Yet one would hardly think of the Medea archives as a hypertext play.

A more interesting question than why Bly created We Descend as a hypertext is why he chose Storyspace, since this particular authoring system is associated with the kind of nonsequential writing experiments to which Van Looy and others were more accustomed. Some claims about Storyspace fictions—that they change each time you read them (Joyce 1995, 96); facilitate explorations of visual possibilities of spatial relationships, reflecting “how we really think” (Bolter et al. 1994, 23)—that is, associatively; and challenge meaning making (Bolter 1991, 151)—can be made about hypertext in general. However, what sets Storyspace apart is the way in which it structures and displays information. Text is organized into nodes resembling little boxes that can then be linked by a word or phrase inside the node as well as by the node itself, resulting in multiple paths that challenge a single progression through a work. As seen in the image below, nodes can be nested inside nodes, which allows for deeper structures. Nodes can be moved around, rearranged, and dragged into other nodes, making it possible to visualize structure. The chart and outline views augment visualization.

Bly found it easier to work with Storyspace than with other commercial systems, such as HyperCard. With Storyspace he could “double-click the workspace to create a text window that scrolled by default when it filled up with text.” HyperCard, by comparison, presented writers with “hard boundaries.” As Bly says, “When you’re writing, you want to think about what needs to be said, not whether it’ll fit in a predefined space.” He also found it easy to link text in Storyspace: “select an object or string of text, click a button on the tool palette to set the source anchor, then click again on the destination document, and you were done.” HyperCard, as he remembers it, involved more labor than “click-here-then-click-there.” Storyspace was also “forgiving” and liberating—it didn’t force writers to commit to an outcome before the work was don—“so much of early writing is groping & dithering, as we all know well,” Bly says. HyperCard would have forced him to “build the territory before [he] could explore it.” Storyspace allowed him much more freedom to explore (Bly, email to Grigar, August 5, 2015).

Bly also did not want the slick look of a HyperCard text. “One factor that decided me against Hypercard is one of its greatest strengths,” he says, “its awesome (albeit one-bit) graphics. When you made a Hypercard thing, it really looked like something. And I didn’t want that, somehow” (Bly, email to Grigar, August 21, 2015; emphasis in original). Notably different is McDaid’s approach in the Funhouse. To some extent McDaid shares Bly’s archival principles, but McDaid’s concept of the “modally appropriate” is inflected through the personality of a multimedia artist. Van Looy’s critique of We Descend homes in on the work’s aesthetic, remarking that it is not “exactly visually stunning” (2002). However, his complaints confuse Eastgate Systems Inc.’s graphics—its logo and the included photograph of Bly—with Bly’s words. They, not images, are Bly’s focus. In the entire hypertext Bly only provides two images, both black-and-white and built from ASCII characters: the opening image of the SkyBanner and the image of the conference. Even if Bly had wanted to provide more robust media for We Descend, he could not have done so. The work was limited by the 3.5-inch floppy disk’s storage capacity of 1.44 MB. In 2002, when Van Looy reviewed We Descend using Storyspace Reader version 1.3.0 b 1, CD-ROMs with a storage capacity of 650 megabytes—equivalent to over 450 floppy disks—had replaced the earlier media. No matter which version of We Descend Van Looy was reading, the digital world he was experiencing in 2002 was vastly different than the world of black-and-white, text-based fictions from which We Descend originated. By the late 1990s, works of electronic literature published on CD-ROMS, such as Myst and TOC, were taking advantage of color images, animations, and sound in ways not previously possible. As Bly tells us:

The structure of We Descend is built of words not pictures, in part because I don’t think in images but in phrases—that is, aurally not visually—but I also didn’t want to interfere with the reader’s ability to imagine for herself what Egderus’s world looks like. I’ve long felt that the saying “a picture’s worth a thousand words” is a canard; rather, a thousand words create a thousand pictures. (Bly, email to Grigar, August 5, 2015)

Thus, when Bly conceptualized Egderus’s archives, he saw them as “writings, not images.” Writings, we must remember, “encodes a voice,” while “pictures are silent.” For Bly “a painting or photograph has rhythm and harmony” but “a voice speaking IS music.” In the end, Bly saw HyperCard as “too noisy for what We Descend wanted to be.” It would have forced him to “build the territory before [he] could explore it.” HyperCard’s look and feel would have “drowned out” the words—“or so I thought. Or just decided” (Bly, email to Grigar, August 5, 2015). Bly chose Storyspace because it was the medium best suited to his vision of an archive.

Bly’s intervention as Curator and Translator serves both as another story nested within the others and as a meta-narrative for the work. Of note, the page at the end of the default path is titled “Da Capo,” Italian musical notation for “go back to the beginning.” Indeed, we see what appears to be the same menu of items with which we started We Descend. But the foreword is replaced by an afterword, and the directions by credits. Clicking on the inventory, readers find the list of authors: Scholar, Egderus, Superius Frater, Historian, Robenc, Aric, Remnant, and Ancients. Missing is the Good Doctor.

This structure means that once readers finish reading the archives, they may not be aware at first how to return to them readily. However, clicking any of the names on the inventory’s list takes readers to that author’s “book plate,” where his writing or writings are listed. As the book plate shows, Bly color-coded the paths so that green titles designate the default path and anything titled in blue is off the path (Bly, email to Grigar, August 21, 2015). Clicking any title moves readers to the bookplate of that title. For example Aric is attributed with two Writings, “Aric: Gig’s Death,” that is part of the default path, and “Aric: Aftermath,” that is not part of the default path. Clicking on the first of these takes readers to that Writings’ bookplate. Clicking on the words, “Aric Gig’s Death,” takes readers to the Annotator’s prologue for that title, but when readers click the lexia anywhere else, they are taken to directly the Writing.

Less intrepid travelers who avoid the inventory may be left at the end of their exploration of the archives with only the Annotator’s voice. In any case, the Good Doctor’s absence from the list can be interpreted as history’s revenge on the man who caused Egderus’s beloved, his former master, and Egderus himself so much pain. It is not some arbitrary gap in information that causes the Good Doctor’s omission but rather a decision made by an arbitrator of truth—the Annotator. Like the Golias, who is suspected of preserving only truths he deems acceptable, and like the Scholar and Egderus, whom the Annotator suspects of inventing some elements in the stories, the Annotator and Bly may be guilty of peddling falsehoods. Evidence of this shiftiness is found in Bly’s afterword, where he reminds us, “Every literate civilization believes itself to be the Remnant, descending from righteous, not to say divine forebears, from whom also it has descended … in glory, majesty, power, discernment, virtue.”

The use of the word “descending” is telling. In his Traversal interview, Bly points out that We Descend is concerned with “evolutionary descent” (Bly, 2015, “Interview, Part 3: The Excavation Explained”). We refer to ourselves, as Bly reminds us, as “descendants” of those who preceded us, rather than as their “ascendants.” Metaphorically, the word hints at Plato’s fallen souls of men, a downward spiral, and the journey downward into Dante’s hell full of sinners. Looking at the way we move through the archives, its three sections and hundreds of lexias, we see that all texts leading up to this narrative serve as layers of historical information that readers literally access one lexia at a time.

There is no way to get to the inventory than by the default path, using an appropriate vintage system. To arrive at this point of the story, this author had to click on precisely 108 lexias in succession. Each click creates a new layer atop the last. We are not digging down when reading We Descend, but, rather, dredging up the story. There is no change of location. We are where we are for the duration. In our evolutionary journey, we are who we are. All of the evidence in the world cannot budge us from ignorance much less protect us from darkness and storms. The irony of this situation is captured in the title.

Bly ends his afterword by cautioning that “the act of recording a story may be just one way of telling it, true, but in the teller’s mind it’s a way of telling it once and for all.” This notion of multiple ways of “recording a story” is reflected in our Traversal methodology. Capturing first the author and then readers moving through a work provides a method of data collection resembling what Clifford Geertz describes as “thick description”—that is, “a multiplicity of complex conceptual structures, many of them superimposed upon or knotted into one another, which are at once strange, irregular, and inexplicit, and which he must contrive somehow first to grasp and then to render” (Geertz 1973, 10). As we learn from Bly in his interview, the complexity of We Descend occurred organically, using Storyspace as a “word processor” (Bly 2015c) rather than the hypertext authoring system that it was. Thus, he did not see himself programming a hypertext but instead authoring an archive of stories that used hypertext as its structuring system.

If indeed this is the case, then even the Annotator’s efforts to question the text and bring discrepancies to light can be read as futile. Readers of the default path may be fooled into thinking We Descend closes on a very depressing note, for, as pointed out previously, they never learn what happens in the various other plots.7 However, if they consider Bly’s focus on authenticity, they may realize that We Descend is at its core an existential work pondering what it means to be genuine to one’s self. Bly answers his original question—what does it mean for a document to be authentic?—with the claim that a document should adhere to the basic values of a culture, even as values are constantly shifting. Authenticity is not exactitude. It does not require evidence to support its veracity. It is essentially mythos, which in the classical sense simply means the story of a people, or the set of stories that best represent a culture’s beliefs, what lies deep in the hearts and minds of a people. To find authenticity, therefore, we must descend inside ourselves, dig past ambition, past desire for revenge, and past ego. According to We Descend, we may encounter as many authentic documents as we “believe … [in our] heart to be true,” with the caveat that we must “be prepared to abandon that truth the instant it plays [us] false.”

It’s interesting to think about Bly’s notion of truth as it plays out in the Traversal. Our videos documenting author and reader performances provide a level of textual authenticity that future scholars can believe—or not. If they believe, then our project keeps the works performed alive and available to be studied, thus preserving an element of late-twentieth-century digital culture. If they don’t believe—and, given the susceptibility of video to doctoring, this is a possibility—then our work is folly: just as careful carbon-dating of dinosaur bones is discounted by those who believe humans existed alongside the beasts, so may be the idea that men and women made literature on little gray boxes called computers in some dark and forgotten past. We are like Egderus, scriptors preserving the past with no idea of what the future brings. Perhaps we will succeed in convincing readers of the future that We Descend and the rest of the works in this volume are true and worthy of remembrance. Perhaps Bly is right when he claims, “Every literate civilization believes itself to be the Remnant, descending from righteous, not to say divine forebears, from whom also it has descended … in glory, majesty, power, discernment, virtue.” Returning to Bly’s statement, as redundant as it may seem, is part and parcel of hypertext, for in these texts ideas may be revisited and so emphasized––and perhaps be remembered.