Christians continued to be barred from central Tibet at the end of the nineteenth century, causing missionary efforts to focus on the perimeter of the Tibetan world. Occasionally, however, courageous believers dared to break through the barrier and travel into central Tibet, heading for their desired destination of Lhasa. Their deeds are legendary, but also filled with sorrow and pain as Satan threw everything at them to stop the light of the gospel being shared in the Tibetan capital.

Kham མས་

In the Kham region, a steady trickle of Evangelical missionaries began to make their presence felt. James Hutson of the CIM later reflected on the changes that had taken place among the Kham during the 1890s. He wrote:

When I first went to those districts the Tibetans used to stand about 30 yards from me and stare at me. If I attempted to approach them they ran away, and it was no use trying to run after them, because they simply ran faster. The only thing to do was to stand and let them stare until they were satisfied that I was a human being, and then to go again the next week, and next year; and so gradually get closer to them.

I well remember the first Tibetan who ever took a printed copy of the Scriptures out of my hands. His first act was to smell it. After he had smelt it he threw it far from him. The smell was too much for him. He thought that there was something uncanny about the smell of the paper and the printing press . . .

As the years have gone by a great change has come over the Tibetan people, and now it is not a matter of our running after them, or their throwing the Gospels away. We can hardly get enough to supply the demands of the people . . .

One evening, I happened to be giving away Gospels when a Tibetan passed by the front of our chapel and I gave him a catechism in Tibetan and a Gospel. He put out his tongue, which is the Tibetan method of saying, “Thank you,” and went on. A few moments afterwards I looked up the street and saw several of these Tibetan people running toward the preaching hall . . . with hands held out to receive the printed Word of God.1

Amdo ་མདོ་

For countless centuries the Amdo region of north-east Tibet had sat undisturbed by the servants of Jesus Christ. That all started to change in the 1890s, however, when several intrepid Evangelical missionaries entered Amdo.

William Christie and William W. Simpson arrived in Gansu in 1892, commencing long and distinguished missionary careers that would result in thousands of Amdo Tibetans hearing God’s plan of salvation for the first time.

Several years later, in 1896, two Swedish brothers, Martin and David Ekvall, arrived in the area and set up base at Minxian in southern Gansu—a strategic location straddling the border of the Chinese and Tibetan worlds.

Simpson served energetically with the Christian and Missionary Alliance (CMA) for the next two decades, but when he attended a conference in 1912 he had a Pentecostal experience and admitted that he had spoken in tongues. This practice was incompatible with CMA beliefs, so Simpson resigned from the denomination and joined the Assemblies of God.

For many years the Christie, Simpson, and Ekvall families served among the Tibetans with great courage and tenacity. Their children were born in this forgotten corner of the earth, and tellingly, when they grew up most of them also chose to serve Christ among the Tibetans.

David Ekvall wrote an excellent account of the work among the Amdo Tibetans in 1907,2 before he unexpectedly received his call to heaven five years later. His son, Robert, grew up to become a key figure in the evangelization of the Amdo, and surpassed his father by writing numerous books on various aspects of Tibetan life; several of these included accounts of Christian work in the region.3

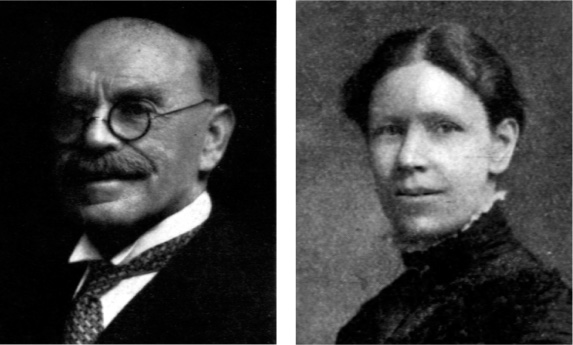

Cecil and Eleanor Polhill

Among the Evangelical missionaries living among Tibetans were the China Inland Mission’s Cecil and Eleanor Polhill.4 Cecil and his younger brother Arthur were two of the famous “Cambridge Seven”—students from Cambridge University who surrendered their lives to missionary service in remote areas of the world after being convicted by the preaching of the famous American evangelist Dwight Moody.

Cecil and Eleanor Polhill

After Cecil reached China in 1885, he moved to Qinghai Province and focused on the needs of the Amdo Tibetans. He married Eleanor Marsden in 1888, and they later moved to the walled town of Songpan in north-west Sichuan. For the first few months all seemed to be going well, and they made many Tibetan friends as they traveled around the region.

The Polhills’ progress suddenly stalled in July 1892, however, when the people of Songpan rioted and nearly killed the couple. A severe drought had afflicted the region, and the spirit-priests blamed the change of weather on the presence of the missionaries. As each day passed without rain, the rancor grew stronger. Then unexpectedly on July 29:

A mob seized and beat Cecil with boards taken from a paling. They bound him hand and foot, and threw him down in the blazing sun while they stood round and cursed. Eleanor suffered almost like treatment, but the children were rescued by friendly neighbors. Their two Chinese servants were also bound and beaten, and then all of them were led through the streets and out of the city gate to be tied up till the rain came.

They were finally rescued by the magistrate, but the crowd would not be satisfied till the two Chinese servants offered themselves to be beaten till their flesh was raw, after which large wooden collars were put on them. The crowd then dispersed, and two days afterwards the little party left the city under an escort.5

The believers, including Eleanor, had been stripped to the waist during the beatings they endured, and their two Chinese Christian servants, Wang and Zhang, were flogged, beaten with sticks, and placed in cages to boil in the hot sun. Zhang considered the persecution a great blessing from God, and later remarked: “I couldn’t help smiling . . . When we were being marched through the town with wrists tied, we were in a very small way like our Master, Jesus Christ.”6

Years later, an elderly Christian man told a missionary that he had witnessed the persecution at Songpan and was so impressed by the Christians’ attitude that he decided he must look into the faith, and he too became a believer.

Although the Polhills were forced to leave Songpan, the town was such an ideal location for outreach to Tibetans that it was not long before new missionaries arrived to take their place. The Polhills had a total of six children (three sons and three daughters), and continued to serve on the northern edge of the Tibetan world at Xining until the outbreak of the 1900 Boxer Rebellion, when the British Consulate ordered them to leave.

Eleanor died in 1904 after an illness. In the last few weeks of her life, when it became apparent the end was near, her devoted husband asked if she regretted marrying him because of all the troubles, hardships, and deprivations they had experienced together. Eleanor immediately replied: “No, we have had a lovely time together!”7

Cecil was a highly regarded Anglican missionary, but after returning to England he received a large inheritance and embraced Pentecostal theology. In 1908, he traveled to America and participated in the Azusa Street revival, and he wrote a large check which paid off the mortgage on the Azusa Street building. Pentecostalism was considered a heresy by many conservative Christians at the time, and Polhill was forced to resign from the Anglican Church. He subsequently became the first president of the Pentecostal Missionary Union.

Notes

1 J. Hutson, “Among Chinese Tibetans, Aborigines, and Muslims,” China’s Millions (July 1918), p. 64.

2 See David P. Ekvall, Outposts, or Tibetan Border Sketches (New York: Alliance Press, 1907).

3 See Robert B. Ekvall, God’s Miracle in the Heart of a Tibetan (Harrisburg, PA: Christian Publications, 1936); Robert B. Ekvall, Gateway to Tibet (Harrisburg, PA: Christian Publications, 1938); and Robert B. Ekvall, Tibetan Sky Lines (New York: Farrar, Straus & Young, 1952).

4 For much of the early years of his missionary career he was known as Cecil Polhill-Turner, but he dropped Turner from his name and was thereafter referred to as Cecil Polhill.

5 Ebe Murray, “Missionary Effort for Tibet,” China’s Millions (August 1897), p. 103.

6 A. J. Broomhall, Hudson Taylor and China’s Open Century, Book Seven: It Is Not Death to Die! (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1989), p. 165.

7 China’s Millions (February 1905), p. 21.