Kham ཁམས་

It was hoped that the 1910s would continue to see a rapid expansion of Evangelical work in Tibetan areas. In Sichuan Province, however, the hoped-for infusion of new missionaries did not occur because of a lack of suitable candidates, while constant violence meant that travel in the Kham region was too dangerous to consider. Frustrated by the lack of progress, in 1912 John Muir highlighted the differences between the Evangelical and Catholic efforts among the Khampa Tibetans at that stage:

In all our territory we have never had more than two Evangelical mission stations. Today the one at Batang is without missionaries, on account of the disturbances, and at Kangding there is only one. When we were first acquainted with this district in 1906, we found that there were four Catholic mission stations in this territory. They took advantage of every opportunity that has been presented since then, and have now added three more, while we stay practically where we were . . . Ought we to be less zealous than they? Or shall we permit them to be the teachers of the Tibetans?1

A Tibetan noblewoman with a ceremonial headdress, 1910s

The few Evangelical missionaries stationed in Kham bravely carried on the work, although they frequently battled discouragement, and saw almost no fruit despite their faithful and consistent sowing of God’s Word.

Every now and then, however, something would happen to lighten the missionaries’ burdens and boost their faith. One such incident occurred in 1917, when the Norwegian missionary couple Theo and Cecile Sorenson received a letter from a living Buddha (a person considered a reincarnation from a lineage of lamas, who is charged with perpetuating a particular school of Tibetan Buddhist teaching). This man had heard the gospel for the first time during a visit to Kangding. In part, the letter said:

I, your humble servant, have seen several copies of your Scriptures, and having read them carefully, they certainly made me believe in Christ. I understand a little of the outstanding principles and the doctrinal teachings of the One Son, but as to the Holy Spirit’s nature and essence, and as to the origin of this religion I am not at all clear, and it is therefore important that the doctrinal principles should be more fully explained, so as to enlighten the unintelligent and people of small mental ability.2

The long-established Catholic work in the Kham region continued to experience harsh persecution. On June 12, 1914, Tibetan bandits ambushed and murdered French missionary Théodore Monbeig and his servant Bang Tunjrou, as they rode toward Litang. When Monbeig’s body was examined, his fellow missionaries noted “13 wounds, almost all mortal: five blows from a rifle, six blows from a sabre, and two stone blows.”3 All the foreigners living in Batang, including the Evangelical missionaries, attended the funeral and offered their respects.

Monbeig had been stationed among the Kham in northern Yunnan Province, where he had:

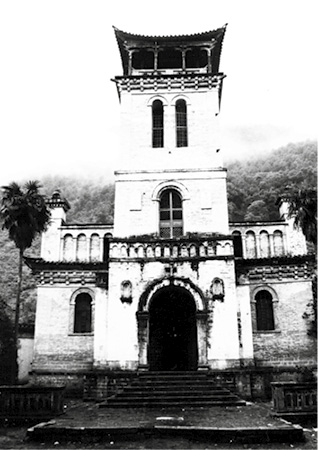

wanted to have a church like one that is found in France. It had to be made out of stone, and contain a bell-tower with a beautiful bell. He knew the enemies of the gospel would find demolishing a stone building more difficult than the flimsy ones they had previously constructed, and so he set about the extraordinary task of obtaining the necessary materials to realize his dream.4

The Cizhong Tibetan Catholic cathedral—a slice of France on the Tibetan Plateau

Julian Hawken

The Tibetan Catholics welcomed Monbeig’s audacious plan when they heard about it, for the Buddhists had often mocked their poor church buildings compared to the ancient citadels of wealth and power that were the Buddhist temples and monasteries. After many years of labor the new French-style cathedral was completed. It still sits today at Cizhong, south-east of Deqen, and serves as a reminder of the decades of selfless service performed by Catholic missionaries in that remote location.

Amdo ཨ་མདོ་

The Buddhist lamas and monks of the famous Labrang Monastery in Amdo territory encountered many difficulties throughout the 1910s, after Gansu Province came under the control of a Muslim general. Disputes over land resulted in the monastery being burned to the ground by the Hui Muslims, and hundreds of monks were put to death in the ensuing carnage.

At this crucial time, Tibetan leaders approached a CMA missionary in the area, J. P. Rommen, and asked him to mediate with the general on their behalf, and to plead with him not to destroy the surrounding Amdo communities. When he spoke to the Muslim general, Rommen “not only represented the Tibetan cause, but also spoke of the freedom he hoped he would now have to travel about where Buddhism had been so devastated and do missionary work.”5

Although the Amdo region is primarily located in today’s Chinese provinces of Qinghai and Gansu, parts of north-west Sichuan also fell under the domain of the Amdo rulers. The remote Amdo area known as Ngapa (Ngawa in Chinese) was later incorporated into Sichuan Province and renamed Aba Prefecture. The Evangelical missionaries who served in Ngapa in the early twentieth century recounted this fascinating story of a brief encounter with an unknown tribe:

A deputation from Ngapa came with a request for pith helmets, guns, and Bibles. Their interest in the gospel, like the order, seemed mixed, but . . . 11 years later, a prince from Ngapa greedily bought up 500 Scripture portions. The prince said: “They are not for sale. My people are interested in this gospel.”6

Buoyed by such incidents, Christians continued to distribute Tibetan Gospel booklets to as many people as would accept them. Interestingly, missionaries in Tibet often found that people were attracted to one gospel story above all others—the Prodigal Son.

Tracts and posters were printed to help tell the story, which invariably left the Tibetans transfixed and seemingly able to relate to the various characters. Men sighed when they thought about how their lives had followed the same pattern as the wayward son, while others saw in their own family members the character of the older son. All were touched by the father’s willingness to forgive and embrace his lost child. This afforded an opportunity to share the gospel more deeply, and many Tibetans heard of the forgiveness of God toward all who are willing to repent of their sins and place their trust in Him.

French Ridley

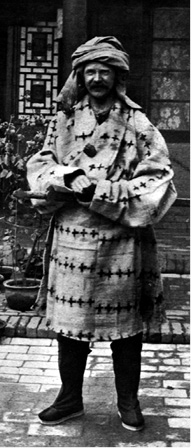

CIM missionary Harry French Ridley served among the Amdo Tibetans for many decades from his base in Xining. Born in the English county of Northumberland in 1862, Ridley came from a strong Methodist family, with relatives renowned throughout the area as mining engineers. Ridley was called to mission work when he was 17, although it took a further 11 years before he finally sailed for China as one of 35 new CIM recruits in 1890.

His first posting was to the Hui Muslim region of Ningxia in north China, where he met and married a single missionary, Sarah Querry. Immediately after their marriage the newlyweds moved to Xining on the edge of the Tibetan world, where they were appointed to lead the work by veteran missionary Cecil Polhill.

French Ridley in his Tibetan clothes

After initially receiving a hostile reception, the Ridleys’ standing in the community greatly improved in late 1895, after 18 Muslim villages rebelled and conflict broke out. A steady stream of refugees came into Xining, and although the Ridleys had no medical training and Sarah had just given birth, they set to work treating up to 200 wounded people each day. One account says:

Ridley himself nearly died of diphtheria. The dead were simply thrown into the streets . . . Hundreds of wounded thronged the Ridleys, brought on stretchers or carried on men’s backs. Mrs. Ridley stayed alone in the house with her child, treating those who came to her, while her husband went out to work on their 2,000 patients.7

The incredible self-sacrificial actions of the Ridleys earned them a newfound respect, and for the remainder of their years in Xining the people treated them well.

Western China at the time was rampant with disease and danger, and three of the Ridleys’ four sons died in childhood, with two perishing from scarlet fever. Through many years of pain and suffering, French and Sarah continued to serve God faithfully, and they were finally encouraged when locals began to repent of their sins and place their trust in Christ. China’s Millions reported “nine baptisms in February 1906, six in March 1907, and another 15 in December 1907.”8

The living Buddha and the Dalai Lama

The Ridleys continued to reach out to Tibetans whenever they could, and in 1911, French shared a story about a living Buddha who dropped by when he visited Xining each year:

We entered into conversation with him, and I gave him a copy of the Gospels of Matthew and Mark. He took the books away, like many others have taken a book away. But the following year he came back again and after a conversation he said, “I read those books that you gave me last year. I saw what was said in them about Jesus Christ and I am very much interested. Would you like to give me some more books?”

I gave him the Gospels of Luke and John. He read the books, understood what he read, and he came back the following year again and said, “I enjoyed those books very much indeed . . . I should like to have a copy of Acts and of Revelation.”9

Ridley wasn’t sure how the living Buddha knew about the other parts of the New Testament, but he wrote to the British and Foreign Bible Society and purchased an entire Tibetan New Testament to give to his inquisitive friend. The man was overcome with emotion when he received the gift. Ridley recalled:

He sat down on the pavement, with his back against a pillar, and I saw him peering over this book, his whole face beaming with smiles . . . He said, “Is this really for me?” “Yes,” I said, “it is for you. Take it away . . . I want you to take it down to the monastery and read it through carefully” . . .

He took it to the monastery, some four days’ journey distant, and I believe that day after day, and every day, that man is looking carefully through the book. Let us pray that this living Buddha may soon find the living Christ.10

The Ridleys also came into contact with an even more famous Tibetan, after the British military seized control of Lhasa in 1904, causing the Thirteenth Dalai Lama, Thubten Gyatso, to take refuge in the Kumbum (now Ta’er) Monastery in Amdo for one year. The Dalai Lama and Ridley got along well. Reporting on one of their conversations, Ridley said the Dalai Lama told him that “Christianity is a progressive force and Buddhism would decay before it.”11 The Englishman also “had the joy of giving him the four Gospels in Tibetan, well bound.”12

French and Sarah Ridley settled in for what they expected would be many more years of service among the Amdo Tibetans, but plans were derailed when Sarah suddenly contracted typhus and died in August 1913. French deeply grieved the loss of his wife, but he continued in the work, loved by the people of Xining. It was said that “the Xining people took a special pride in him because he spoke their strange dialect, and its weird expressions and tones could be recognized wherever he went.”13

Ridley increasingly invested his time among the Tibetans, and was thrilled when the first Tibetan believer was baptized in 1923, a full 33 years after he had first arrived in China.

In 1932, French Ridley finally retired to the peaceful countryside of Northumberland, having spent 38 years of his life in China. He died in 1944 at the age of 82.

Notes

1 John R. Muir, “Tibet’s Condition and Need of Workers,” China’s Millions (August 1912), p. 98.

2 China’s Millions (November 1917), p. 120.

3 My translation of the Théodore Monbeig Obituary in the Archives des Missions Etrangères de Paris, China Biographies and Obituaries, 1900–1999.

4 Théodore Monbeig Obituary in the Archives des Missions Etrangères de Paris.

5 J. P. Rommen, “Another Foothold for the Gospel in Tibet,” The Alliance Weekly: A Journal of Christian Life and Missions (June 7, 1919), pp. 168–9.

6 Milton D. Stauffer, The Christian Occupation of China (Shanghai: China Continuation Committee, 1922), p. 277.

7 A. J. Broomhall, Hudson Taylor and China’s Open Century, Book Seven: It Is Not Death to Die! (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1989), p. 236.

8 “My Great Great-Uncle: Missionary to China,” China Insight (March–April 2002). Although the ethnicity of these believers is not mentioned, it is likely that most or all were Han Chinese.

9 H. French Ridley, “Then and Now in Siningfu, Kansu,” China’s Millions (July 1911), pp. 102–3.

10 Ridley, “Then and Now in Siningfu, Kansu,” p. 103.

11 Mrs. Howard Taylor, The Call of China’s Great North-West, or Kansu and Beyond (London: China Inland Mission, 1923), p. 136.

12 Ridley, “Then and Now in Siningfu, Kansu,” p. 102.

13 China’s Millions (May–June 1944), p. 23.