The 1940s saw an increase in the number of Tibetan Christians as the large amount of faithful sowing of God’s Word finally began to reap a harvest.

In a culture steeped in black arts and demonism, strong opposition to Christians was to be expected. One new Tibetan Christian, a man named Chepel, excitedly returned home to share his new faith, only to be murdered by his own friends and family members.1

With central Tibet still locked behind spiritual iron gates during the 1940s, the gospel could only whittle away at the great stronghold from the perimeter, and literature distribution represented the main way the message of Jesus Christ reached people’s hearts on the Roof of the World. In 1947, two female missionaries, Mildred Cable and Francesca French, wrote about the impact that Gospel literature was having in Tibet:

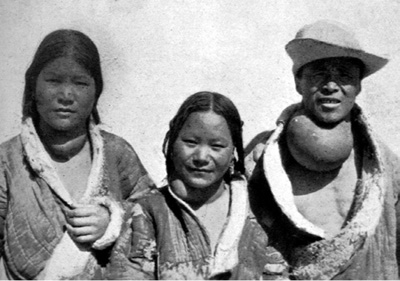

This Tibetan family was successfully treated at a mission hospital for the large goiters around their necks

The Gospels which are carried off into Tibet are never left unread, for even where an illiterate man accepts them, he takes them back to his encampment and hands them over to his kinsmen at the lamasery, where all the lamas will listen while one reads aloud to the assembled disciples and to any herdsmen who may gather round.

Very often the people in one settlement will all have heard the gospel before the living Buddha decides it is a dangerous book, which may cause headaches to anyone who reads it. This is by no means always the case, and some lamas have even made it their business to put Christian literature into circulation. There is one lama who still wears the maroon shawl of his order, who is known to be traveling about Tibet preaching Christ wherever he goes.2

Amdo ཨ་མདོོ་

One unexpected challenge that confronted the missionaries in Amdo occurred when the large population of Muslims in the region decided that they, too, could convert Tibetans to their religion. Aided by Muslim officials, they attempted to attract Tibetans to Islam by building roads and other infrastructure for them. Because the Muslims’ message was without hope or power, however, their efforts soon faded, but for a time the environment was made more difficult for the missionaries.

The 1940s also saw a changing of the guard in Amdo as a number of veteran missionaries who had given their all to reach the Tibetans retired and were replaced by new recruits.

A former American naval officer, Virgil Hook, came to live among the nomads in Qinghai, and a short time later reported that he was having a tough time, and was:

enduring great hardships among the 40,000 Tibetan nomads; intense cold at over 13,000 feet [3,962 meters] above sea-level, life in a tent amid raging snowstorms, the constant discomforts of bugs, fleas and lice, and the doubtful delicacies of buttered tea and ancient cuts of meat.3

A breakthrough occurred in a place known as “robber valley” in Amdo territory, following the death of missionary Betty Ekvall, who perished after contracting anthrax. The Ekvalls’ son, David, was attending school in Vietnam at the time and was not aware of his mother’s sickness until he had a vision in which he saw her standing beside the Lord Jesus Christ, who turned to her and lovingly said, “Well done, thou good and faithful servant.” A supernatural peace engulfed David, and when news finally reached him of his beloved mother’s death, his heart was at rest.

Robert and Betty Ekvall with their son David in 1939

Several years earlier when she had suffered another sickness, Betty had prayed to God, asking that her life might be spared to bring Tibetans to faith in Jesus and that her death might also serve the same purpose.

Robert Ekvall was heartbroken at the passing of his wife, but a short time later he visited Drongwa, where he was welcomed into the home of an old Tibetan man. The Ekvalls had shared the gospel with this man many times, but he always seemed incapable of grasping the message.

When the Tibetan asked Ekvall where his wife was, the missionary replied, “She is in heaven with Jesus.” The question and answer were repeated three times, because:

The old man wanted to be very sure he was hearing correctly. Convinced, he immediately replied, “I must believe,” and then prayed, “God, be merciful to me a sinner and save me for Jesus’ sake.”

He then asked his son and grandson if they wanted to follow in the Jesus way, and they gave their affirmation. This was the beginning of a spiritual breakthrough in “robber valley.” During the following months the missionary’s heart was encouraged as he saw family after family turn to Jesus. Hostility was turned to acceptance and goodwill as non-Christians saw the changed lives of their neighbors.

As the Christian community grew, the missionary had to warn overzealous Christians not to force or coerce those who had not accepted their faith, but to win them by their transformed lives characterized by love, joy, and hope.

So it was that in a most unlikely place, “robber valley,” a new prayer was heard: “Our Father who art in heaven.”4

The Borden Memorial Hospital

Lanzhou, the capital of Gansu Province, was the site of a wonderful Christian hospital that served the people from 1934 until it was taken over by the Communists in 1949. The hospital was named after a young American missionary, William Borden, whose family had made millions of dollars mining silver in Colorado. He offered his life for missionary service in north-west China, and was studying Arabic in Egypt en route to China when he was struck down with congenital meningitis and died at the age of 25.

Although the young man never made it to his desired destin-ation, his will had set aside a large sum of money, which was used to construct the Borden Memorial Hospital at Gaolan, just north of Lanzhou.

Although the hospital mainly catered to Han Chinese and Hui patients, a steady flow of Amdo Tibetans also came for treatment, and over the years hundreds who arrived in Lanzhou for physical care were also presented with the gospel. Soon the Christians had gained an excellent reputation among the Tibetan people, and many hearts that had formerly been hesitant were now open to the claims of Christ.

Part of the Borden Hospital, where hundreds of Amdo Tibetans heard the gospel

The most lowly and despised members of society at the time—people suffering from leprosy—also heard about the hospital and came in their desperation to seek help from the missionaries. When they heard that Jesus Christ loved lepers and wanted to grant them eternal life, many Tibetans stricken with this disease repented of their sins and placed their trust in the Savior. It was reported in 1935:

Lepers are coming in such numbers now from Tibet that we have had to seriously consider not receiving them because of shortness of funds. After discussion in our business meeting, it was decided that we could not do this, and so they are still coming. Some of the most sincere Christians among them have died within the last few months, but we praise God that their place is being taken by others, for 12 have just confessed the Lord.5

Christian outreach among the Tibetan lepers enjoyed sustained success, with a visitor to one of their church services reporting in 1950:

The fervor and reverence the leprosy patients produced and the accuracy with which they recited Scripture portions from memory showed unmistakably that to many of them these things were real, more real than their deformities and aching leprous bones. Some have found refuge in Jesus, and will be granted free and glorious entrance to the streets of the New Jerusalem. Others of them still resist their only hope of salvation, proudly going their own way, in danger of becoming outcasts from heaven itself.6

Many Tibetan nomads arrived at the hospital seeking treatment for goiters, some of which grew to an enormous size around their necks. This affliction affected many nomads because of their smoky, unventilated tents, and the lack of iodine or fruit and vegetables in their diets.

The People’s Liberation Army took control of Lanzhou in August 1949, and the Borden Hospital was taken over. Much frustration was felt by the missionaries as they believed they were on the cusp of a great breakthrough among the Tibetans when the Communists brought a sudden end to their work. Although it only functioned for 15 years, the facility had made an impact on the lives of thousands of people, healing their physical ailments and meeting their spiritual needs.

Most of the missionaries associated with the hospital evacu-ated to the coast, but one member of the medical staff, Dr. Rupert Clarke, was placed under house arrest by the Communists and accused of manslaughter for failing to save the life of a dying man.

The end of the missionary era

At Hualong, on the Amdo frontier, a new 12-bedroom mission hospital had been constructed exclusively to treat Tibetans. News of the facility spread far and wide after a living Buddha, “with his entire encampment, arrived with 50 men requiring treatment and 40 needing operations.”7

Visitors to the Hualong Hospital included a sorcerer of the Bon religion. This man sought help for his wife La Mou, who was suffering from two large internal cysts, one ovarian and the other in her liver. One of the missionary-doctors recalled what happened during the woman’s recovery after the surgeries:

We gave the sorcerer gospel literature in his own language, and he seemed really interested. I often saw him sitting by his wife’s bedside poring over these tracts and Gospels, or reading them aloud to her and to the other Tibetan women in the ward . . .

Every morning, before the doctor began his round, there was a short Chinese service in the ward. Sometimes more than half of the patients in this ward were Tibetan and they may have understood very little of the service, but La Mou used to sit up most reverently and try to join in the hymns . . .

Before La Mou and her husband returned to their home far away on the grasslands of Qinghai, she said she was going to be a Christian. Alas, one knows that back in their own country, Tibetan converts are almost certain to meet a persecution of such fierce intensity that few have come through it alive.8

The Hualong Hospital was also shut down by the atheist Communists, who despised all religion and saw no value in keeping the Christian facility open.

The Evangelical missionary era in Amdo, which had started with George Parker more than 70 years earlier, was rapidly coming to a close. In 1950, in a sign of things to come as the baton was transferred from foreigners to the Chinese Church, a group of Chinese Christians shared the gospel in Labrang with great power, “resulting in 20 professions of faith. The event was so newsworthy that it was reported by Tibetans in India.”9

The era concluded with great joy, however, when two sets of married CIM workers—George and Dorothy Bell of Canada, and Norman and Amy McIntosh of New Zealand—baptized two Tibetan women who possessed a true faith in Jesus Christ.

The Bells had been on the mission field since 1927, and the McIntosh family since 1936, but after much sweat and prayers these faithful servants of Christ had finally seen their first Tibetans become children of God. A few years later, Amy McIntosh wrote a booklet entitled Daughter of Tibet: The Story of Drolma,10 which was a gripping tale of how the Tibetan woman had accepted Christ.

Kham ཁམས་

Life in the Kham region was deeply affected by the chaotic conditions that prevailed throughout the 1940s.

The decade saw the Catholic missionaries in Kham continue their long legacy of dying as martyrs.11 French missionary Michel Nussbaum, who had served at Yanjing for 32 years without a furlough, was murdered by bandits in September 1940; while Maurice Tornay from Switzerland and a Tibetan convert named Dossy were shot dead by four Buddhist lamas in August 1949, just weeks before Mao Zedong formally established the People’s Republic of China.12

Evangelical missions went through a painful transition as the foreign missionary enterprise wound down.

Robert and Euphemia Cunningham retired to the United Kingdom in 1942 after investing 35 years of their lives in the Kham region. Robert, who died soon after returning home, had been a leading gymnast prior to becoming a missionary, and “his magnificent physique enabled him to remain for practically the whole of his missionary career at Kangding, over 8,000 feet [2,438 meters] above sea-level.”13

Euphemia, meanwhile, was a gifted linguist, and while other missionaries struggled for years to acquire a useable level of Tibetan, she spoke Kham so fluently that she often had crowds of Tibetan women and children gathered around her as she shared Bible stories with them. At the start, local Khampa women sometimes touched her lips as she spoke, so amazed were they that a white woman could speak their language.

Occasional stories emerged from Kham to encourage believers in the 1940s. One report from Kangding told how:

Slides on the life of Christ provided a great attraction, and sometimes as many as 100 people at a time stood to listen and watch: men with long swords, picturesque garb, and typical Tibetan swagger listened intently . . . A census showed that almost every province of Tibet was represented; some having traveled for months to reach Kangding.

Access to people from all parts of Tibet was in this way gained. Even Lhasa-trained monks, conscious of their special prestige, talked earnestly about the Lord Jesus Christ . . . In 1948 an old Chinese lady and a Tibetan girl boldly confessed Christ in baptism.14

Notes

1 David V. Plymire, High Adventure in Tibet: The Life and Labors of Pioneer Missionary Victor Plymire (Ellendale, ND: Trinity Print’n Press, 1983), p. 219.

2 Mildred Cable and Francesca French, The Bible in Mission Lands (New York: Fleming H. Revell, 1947), p. 94.

3 Leslie T. Lyall, A Passion for the Impossible: The China Inland Mission 1865–1965 (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1965), p. 142.

4 William D. Carlsen, Tibet: In Search of a Miracle (Nyack, NY: Nyack College, 1985), pp. 53–4.

5 D. Vaughan Rees, “Visits from High and Lowly,” China’s Millions (March 1935), p. 53.

6 Keith Cameron, “Lanchow: Medical Outpost of Central Asia,” China’s Millions (March 1950), p. 28.

7 Lyall, A Passion for the Impossible, p. 144.

8 H. D. Laycock, “The Sorcerer’s Wife,” China’s Millions (September–October 1948), p. 53.

9 Lyall, A Passion for the Impossible, p. 144.

10 Amy McIntosh, Daughter of Tibet: The Story of Drolma (London: China Inland Mission, 1951). McIntosh also wrote a 50-page booklet entitled A Tale of Tibet: The Man in the Sheepskin (London: China Inland Mission, 1950). Although these stories were based on fictional Tibetan characters, they were nevertheless an accurate portrayal of the missionaries’ struggles and victories as they endeavored to reach out to Tibetans in Qinghai. These two booklets are extremely difficult to find today.

11 Accounts of these and hundreds of other inspirational Christian martyrs in China can be found in Paul Hattaway, China’s Book of Martyrs: Fire and Blood, Vol. 1 (Carlisle: Piquant, 2007); and Paul Hattaway, China’s Christian Martyrs (Oxford: Monarch, 2007).

12 See Robert Loup, Martyr in Tibet: The Heroic Life and Death of Father Maurice Tornay, St. Bernard Missionary to Tibet (New York: David McKay, 1956).

13 “In Memoriam: Mr. Robert Cunningham,” China’s Millions (January–February 1943), p. 8.

14 Lyall, A Passion for the Impossible, p. 143.