Ü-Tsang དབུས་གཙང་

Tibetan dreams of becoming an independent nation came crashing down in the 1950s, as massive upheavals struck every part of Tibetan society, and hundreds of thousands of people were mercilessly slaughtered by the Communists.

Between 1913 and 1950, the Tibetan government in Lhasa had tried to assert its authority as a separate country, issuing its own flag, passports, and currency. A Tibetan stamp was printed in India, bearing the image of the Dalai Lama, although as one source pointed out:

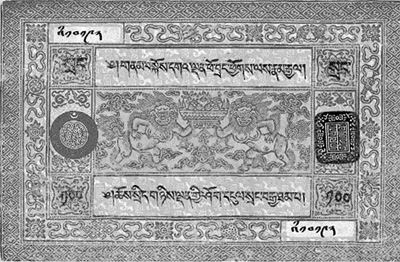

A Tibetan banknote, used in Tibet from 1942 to 1959

These were rejected by the Tibetans . . . The Dalai Lama could not be placed on a stamp as it might get trodden underfoot, which would bring dishonor to him. Besides, who was going to strike his head with a great metal franking hammer?1

Life in Tibet experienced a sudden and dramatic shift after a Chinese general declared in 1951: “Efforts must be made to raise the population of Tibet from two million to more than ten million.” This new policy was to be implemented by waves of Han Chinese migrants moving to the Tibetan Plateau. Unsurprisingly, the Tibetans were alarmed and indignant when they heard about the new initiative.

Christians with a burden to reach Tibet were divided in their views of the Chinese takeover of the land. While some lamented the influence the atheistic regime would have on the Tibetan people, others looked through eyes of faith and saw an opportunity for the gospel to knock down the iron gates that had kept Tibet firmly shut off to Christianity for centuries. Missionary Edward Beatty wrote in December 1950:

Today the armies of Communist workmen are building a motor road across Tibet on which ten-wheel trucks already are moving toward Tibet’s capital, Lhasa. We believe, hope and pray that this road, in the wisdom and power of God, will become a way of advance for those who proclaim the Christian gospel and way of life.

But will Western Christians be permitted to enter in? So long as the Lord has need of them, He will enable His chosen ones to enter the land. In Chinese Tibet we one day listened spellbound to a small group of recently arrived Chinese Christians thanking God that He had reserved Tibet as a special field of service for the Chinese Church.2

George Patterson

One of the most controversial of all missionaries among the Tibetan people was George Patterson, a Brethren believer from Scotland. He lived in the Kham region from 1947 to 1952, siding with the Khampas in their struggle for survival against both the Chinese army and other Tibetan factions. Instead of simply preaching the gospel to the Tibetans, Patterson soon found himself caught up in a complex situation. One historian explained:

George Patterson

He hoped to gain a political and military victory over both the reactionary government in Lhasa, and the approaching armies of the People’s Republic of China. Such a strategy, deplored by most of his missionary colleagues in Kangding, would produce justice for the Tibetans, he claimed. Furthermore, he thought it would enable him as a missionary to develop a new foundation for Tibetan culture, one that would have the gospel as an essential ingredient. The plan did not work.3

Many in the mission world were aghast as Patterson plunged into the murky world of political intrigue. Fully convinced he was on the right path, he even persuaded Khampa warriors to take him along so that he could film an ambush where they massacred a group of Chinese soldiers.4

Further controversy followed when Patterson helped the Dalai Lama to flee Tibet in 1959. This act convinced many missionaries that Patterson had fallen into deception, a view that was only reinforced by his own testimony, in which he claimed to have come to Asia after hearing an audible voice in his home country, telling him to go to Tibet. Patterson admitted:

I knew nothing about Tibet, except that it was a remote country with unusual customs. But I was intrigued enough to begin reading about Tibet, and to begin a personal dialogue with God on the basis that he was the one who had spoken to me.5

George Patterson helped the Dalai Lama to flee to India just before the Chinese forces arrived in Lhasa with plans to either capture or kill the Tibetan leader. The successful escape caused great celebration among Tibetans and has sustained the cause of Tibetan Buddhism to the present day.

Many Christians, understandably, have questioned the wisdom of a professing missionary helping the survival of a man considered by millions of Tibetans to be a living god, but Patterson, as always, remained unapologetic, saying he was doing God’s will and would have no hesitation in doing so again.

Patterson also fled to India and then later returned home to Scotland. Until his death in 2012 at the age of 92, he:

continued to press for Tibetan rights before international bodies, with full assurance that it was God’s will. Tibetan leaders outside of China, including the Dalai Lama, have indicated that Patterson has been a better friend to them than the United States, Great Britain, or India.6

Geoffrey Bull

George Patterson had traveled to China with a Brethren missionary named Geoffrey Bull. The duo intended to spread the gospel among Tibetans, but whereas Patterson went on to become a famous and divisive figure in the mission world, Bull was arrested in the Kham region and spent three years in prison for his faith, before the Communists declared that he had confessed his “crimes against the people” and expelled him from the country. Bull recalled the emotions he felt as his train made its way toward the Hong Kong border and freedom:

Year after year, I had lived for this day. God knows all that it had meant. With blow after blow, I had been spiritually and psychologically bludgeoned, until I was dazed and broken in mind and spirit, but none had been able to pluck me from my Shepherd and His Father’s hand.

In the crisis, I had found my faith and love at times too weak to hold Him fast, but the final triumph was not to be in my hold of Him, but in His hold of me. His love would never let me go. He would keep that which I had committed to Him. In His own time and way, He was determined and able to make me all the man that He had planned that I should be. I was broken, but I had proved His Word unbreakable.7

Geoffrey Bull

Upon returning to Britain, Bull gradually recovered from his ordeal and told his story in a bestselling book, When Iron Gates Yield. He married in 1955 and subsequently served as a missionary in Borneo (now part of Malaysia). Geoffrey Bull continued to be a leading Brethren teacher for decades until his death in 1999 at the age of 78.

Kham ཁམས་

The 1950s saw Khampa society decimated by Mao’s forces as they invaded the region, leaving a trail of destruction in their path. Life in Kham was never to be the same again. In 1950, the Chinese captured the town of Qamdo without firing a shot. The Khampa fled in terror when the People’s Liberation Army set off a huge fireworks display on the outskirts of the town. The Tibetans had never seen fireworks before and presumed they were being bombarded with a new weapon.

In late 1955, the Communist authorities ordered the lamas of the large Litang Monastery to make an inventory of the monastery’s possessions for tax assessment. When the lamas refused to oblige, soldiers laid siege to the monastery, which was defended by several thousand monks and farmers, many of whom were armed with farm implements.

Chinese aircraft were called in to bomb Litang, destroying the monastery and killing hundreds of people. The Tibetans, outraged by the attack, spread the conflict to the surrounding towns of Dege, Batang, and Qamdo.8 They fought for their very existence, not caring whether they lived or died, but their efforts were no match for the Chinese tanks and well-drilled army.

The People’s Liberation Army marching across Tibet in the early 1950s

Rocked by the savagery of the attacks on his people, the Dalai Lama set up a commission which documented some of the atrocities that had been committed by the Chinese against the Tibetan people:

Tens of thousands of our people have been killed, not only in military actions, but individually and deliberately. They have been killed, without trial, on suspicion of opposing Communism, or of hoarding money, or simply because of their position, or for no reason at all. But mainly and fundamentally they have been killed because they would not renounce their religion.

They have not only been shot, but beaten to death, crucified, burned alive, drowned, vivisected, starved, strangled, hanged, scalded, buried alive, disemboweled, and beheaded. These killings have been done in public. The victims’ fellow villagers and friends and neighbors have been made to watch them, and eyewitnesses described them to the Commission.

Men and women have been slowly killed while their own families were forced to watch, and small children have even been forced to shoot their parents.

Lamas have been specially persecuted. The Chinese said they were unproductive and lived on the money of the people. The Chinese tried to humiliate them, especially the elderly and most respected, before they tortured them, by harnessing them to plows, riding them like horses, whipping and beating them, and other methods too evil to mention. And while they were slowly putting them to death, they taunted them with their religion, calling on them to perform miracles to save themselves from pain and death.9

The Chinese had a markedly different view of the conflicts, however, with one account declaring:

The imperialists and a small number of reactionary elements in Tibet’s upper ruling clique could not reconcile themselves to the peaceful liberation of Tibet and its return to the embrace of the Motherland . . . Contrary to their desires, this rebellion accelerated the destruction of Tibet’s reactionary forces and brought Tibet onto the bright, democratic, socialist road sooner than expected.10

In 1950, just prior to the curtain being permanently drawn on foreign Christian work, missionary Edward Beatty provided a final glimpse into the state of Christianity throughout the Kham region:

In the town of Kangding there are four full-blooded Tibetans who are Christians; one is a gifted artist who was formerly engaged in the lucrative work of idol painting. There are also four or five Christian women of Chinese-Tibetan parentage, more Tibetan than Chinese. Finally, there were three other Tibetans called of the Lord, for a time, to the preaching of the gospel, who are now in His presence in glory.

A 1955 Chinese propaganda poster of smiling Tibetans after being “liberated” by the Red Army

Workers of another mission living in the small town of Garze were privileged to see four or five Tibetans baptized on confession of their faith in the Lord Jesus. Also in several villages of Chinese Tibet there are other Christian Tibetans.11

Due to the godly influence of missionaries like Albert Shelton, the remote town of Batang had become a hub of Christian activity in the Kham region prior to the chaos of the 1950s. Years later, a Tibetan Christian using the pseudonym “Andrew” detailed the impact the gospel had made there:

I was born into a Christian Tibetan family. By God’s favor I was led into His presence in my early childhood and became part of the Christian flock. Through the teaching of church members I grew up to become a servant of Jesus Christ. God blesses and preserves me all the time. Thank you Lord! I will glorify and serve Him all my life . . .

Many Tibetans became believers in those days. People repented after hearing the Word of God, and began living by the truths of the gospel. They accepted the Lord’s redemption, proclaiming Jesus as the only God, who came to earth in bodily form as a human being. Tibetans followed and served the Lord with faithful hearts. Many of them were baptized as well. When Christianity was prevalent in Batang, there were more than 100 believers. God blessed us abundantly.12

The long Catholic missionary era in Tibetan areas also came to an end in the early 1950s. The Kham region, with thousands of converts, had seen the strongest results for Catholic work among Tibetans, with even a rival Evangelical scholar admiring their commitment and strategic approach:

Catholic missionaries lived simple lives among nomads and learned well the life and culture of the people. They were prepared to dialogue philosophically with the lamas or to deal directly with village people on their fears of the spirit world. Seeking wherever possible to promote people movements, they were able to establish Christian communities to which they then ministered through hospitals, schools, seminaries, and institutions of compassion. Their work on both sides of the China–Tibet border has proved to have more lasting quality than any of the many ministries engaged in by Protestant missionaries in the same areas.13

John Ding

It was not only Tibetans who felt the full force of Communist fury. Han Chinese evangelists who had given their lives to reach the Khampa Tibetans also faced years of savage persecution because of their love for Jesus Christ. Two little-known heroes of the faith were John Ding and his wife Ju Yiming, who were serving in Kangding when the People’s Liberation Army swept through the area.

Ding, a native of Shanghai, thought God might be calling him to Tibet when he met a beautiful young Christian lady named Ju Yiming. His cautious nature resulted in him taking his time before asking Ju to be his wife, and when he finally mustered enough courage he said, “Perhaps I’m not what you would want in a husband. You’re like a Mary while I’m more like a Martha. I’m Mr. Fix-it, while you are a scholar.”

“Those differences could complement one another,” Ju replied.

When Ding told her that he thought God might be calling him to a life of missionary service among the Tibetan people, Ju replied, “Well, if you are my husband, I’ll certainly go where you go. And if that means Tibet, so be it.”14

When the newlyweds arrived in Kangding in 1949, they were amazed to see the variety of believers in the town’s thriving church. Ding recalled:

We had an assembly of great variety: Han Chinese, Westerners, and some Tibetans; Christian workers, a few old believers, many new converts, and some inquirers. Never before had this church had such a harvest as this, and never before so many workers in the harvest.15

The years passed, and all foreign missionaries were expelled from China. After several years of relative calm, November 29, 1958, proved to be a horrible day for Ding and Ju, when several soldiers burst into their home with their guns drawn. They dragged the couple away, as Ding looked at his beloved wife and said, “The time has come. Hallelujah!”

She responded: “Yes, the time has come; praise the Lord!”16

Many years later, John Ding recalled the events of that fateful evening:

One of the men demanded: “Where are your guns? We know you have them!”

I picked up my Bible. “This is my weapon,” I said quietly.

They ignored this but roughly told us: “We’re taking you to prison. Get a quilt and any other necessities and be quick about it!” Yiming whispered to me, “Take a Tibetan gown. It will keep you warm.”

Following her advice, I chose my grey wool robe; little realizing that it would stay with me for the next 22 years, though by that time somewhat threadbare.17

Ding discovered that he was one of the few Han Chinese inmates in the prison, and that almost all the other men were Khampa warriors who had been labeled separatists and counter-revolutionaries by the Communist authorities. After a few weeks, the Tibetans saw that Ding was different from other Chinese. He was humble and seemed to genuinely care for them. They treated Ding like one of their own, which brought great comfort to Ding once his hardships began in earnest. He recalled:

I was beaten; I was strung up by ropes and pummelled. What I particularly remember was that when I was thrown back into my cell, still filled with Tibetans, the lamas clustered around me, examined my bruises, got out some of their precious yak butter, and gave me a gentle rubdown . . .

In turn, I did my best to help the other prisoners when they came limping back after torture. Sometimes we had to witness brutal treatment right in our cell, like the time when one trader had wet yak hide tied around his head and left to dry. When that process seemed to be going too slow, a guard took a chopstick and began to twist the thongs tighter and tighter. The man shrieked in pain. It was appalling and shook us to the core. Of course, that is why we were forced to witness it.18

Months after his arrest, Ding learned that his wife was working as a cook for the wives of the prison staff. He also heard that she was getting into trouble by boldly sharing the gospel with everyone she met.

The time slowly passed, until it had been three years since Ding and Ju had seen each other. John often imagined what his beloved wife now looked like, but one day while he was working outside on a mountain slope, he was shocked and delighted to see her coming up the trail with a basket on her back. He quickly seized the moment, asking how she was. Ding later recalled their precious conversation:

[Ju had replied:] “There have been some bad days. I got reported for witnessing, and the guards beat me for that. Some of the staff women are Christians, and I urged them to be faithful. That got me into trouble. But God has been so good all along.”

Then hearing footsteps on the path, she said, “Someone’s coming.”

“I love you, Yiming,” I whispered. “I pray for you so much!”

“And I pray for you, John, that your faith will fail not.” And with that she moved slowly up the hill.19

John Ding was overjoyed with the brief interaction he had that day, not realizing it was the last time he would see his wife again in this world.

The years rolled on, with John Ding remaining in prison because of his faith in Christ Jesus. Seasons of harsh persecution came and went as China lurched into chaos under Mao’s cruel policies. On one occasion, Ding was called into the prison torture room, where his hands were tightly tied behind his back and a bucket of human excrement was emptied over his head. The guards cruelly left him in that position for days:

never giving him a chance to clean himself. He was given food, but with his hands tied behind his back, he had to lie on the floor and lick it up like an animal. The food had to pass through soiled lips. He still did not deny his faith, and refused to admit to crimes he had not committed . . . The inmates were told they would all be kept like this indefinitely unless they forced him to comply with the demands of his interrogators. To survive, these criminals now competed in torturing him day and night.20

In 1960, Ding was suddenly transferred to a prison in the city of Chengdu, where he spent the next seven years. He was surprised to find that the new facility was also filled with Tibetans, and noted: “All along I had marvelled at the mysterious ways of God in continuing my ministry to Tibetans. I probably talked to more Tibetans in prison than I did while I was outside.”21

Ding was befriended by many of the Khampa inmates. One day the prison warden commanded the Tibetans to cut off their long braids of hair. The order was so loathsome to the Khampa warriors that they were on the verge of rioting in protest. Ding, “who was also a barber, persuaded them to let him cut off their hair by arranging to have each braid labelled and placed in storage with the prisoner’s possessions.”22

John Ding had received no further news about his wife until one day, during questioning, his interrogators casually remarked: “Your wife was just like you. She wouldn’t stop praying, and we had to put her in a struggle session. She wouldn’t give in, even when she was beaten. After that she died.”23

John was crushed by this news and was angry when he discovered that his beloved wife had been dead for three years before he was notified. A short time later Ding wrote a confession of his “crimes,” much to the glee of his captors. He went back and scratched out large portions of it, however, which led to him being sent back to the Kangding prison for another ten years.

Ding was finally released from prison in 1981, after more than 22 years in captivity. He had remained faithful to the Lord, and after moving back to his home city of Shanghai he became a friend of Wang Mingdao, the great Chinese house church patriarch, who had spent 25 years in prison for his faith. The two disciples had much in common.

One day John Ding received a letter from the government, which stated: “We have been re-examining your case, and have come to the conclusion that there is no substance to the charges against you.”24 Ding sighed, fell to his knees as he had done countless times before, and recommitted his life to His Savior, Jesus Christ.

After such prolonged hardship, the last part of Ding’s life could scarcely be imagined. He married a Christian widow, and when his criminal record was erased he procured a passport and was able to visit the United States in the late 1980s at the invitation of some of his former missionary friends. He finally went to his eternal reward in the 1990s.

John Ding in America in the late 1980s

David Woodward

Amdo ཨ་མདོོ་

Massive loss of life was also experienced in the Amdo region, as the Communist “liberation” machine marched through the grasslands and valleys, slaughtering entire communities as they pleased. The Dalai Lama listed 49,049 deaths from battles within Amdo territory, in addition to 121,982 deaths from starvation.25

After all foreign missionaries had been systematically expelled from China, some Han Chinese believers courage-ously volunteered to take their place. In 1950, a seminary graduate moved to Xining, hoping to carry on the decades of sterling service given by stalwarts of the gospel like French Ridley, Frank Learner, and Victor Plymire. He made long journeys into the newly “liberated” Amdo areas, searching for any believers he could find. His report brought great encouragement to the expelled missionaries:

Mao Zedong flanked by the Dalai Lama (right) and the Panchen Lama (left) in 1954

In the country, village Christians are maintaining a testimony and strengthening one another’s hands in the Lord. At one remote place I found four Christian farmers who had had no contact with other Christians for four or five years but, in spite of persecution, they still confessed the name of Christ. Thirty miles farther on, I found one isolated Christian continuing faithful in prayer and Bible reading.

Elsewhere I found the Christians meeting twice daily—in the morning for Bible study and in the evening for prayer, and tithing their money for the Lord’s work. Not far away I was warmly received by a family of Tibetan Christians! At one Tibetan center, the little group of Christians had been revived and backsliders had been restored.26

The “Back to Jerusalem” Tibet mission

In the 1940s, a small number of Han Chinese missionaries received a call from God to labor in Tibet. Among them were some of the first workers with the “Back to Jerusalem” movement.

Li Jinquan was born into a Muslim home. Her parents died while she was young, and she went to live with her grandmother. When just 12 years old, she ran away from home and fell into a life of sin, but when she heard the gospel for the first time at the age of 20, she believed and was saved.

In 1941, Li attended a Bible school, and three years later she joined a short-term outreach to Gansu, where she met Tibetans for the first time. Li testified that:

The Lord touched my heart to see the pitiful need of the Tibetan people . . . The appeal constantly presented itself before me, and I could not but accept this challenge from God . . . The Lord put the load of Tibet on my heart.27

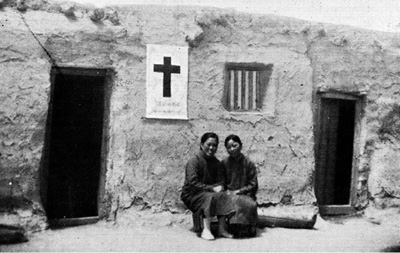

In March 1947, she joined other Back to Jerusalem missionaries and headed west, becoming part of the movement’s Tibet mission. For years she lived in a small mud home in Tulan (now Ulan in Qinghai Province), where she preached the gospel and loved the Tibetan people, until she and the other Chinese missionaries were expelled from the area by the authorities.

Li Jinquan (right) and her co-worker Grace He Enzheng outside their mud home at Tulan

Foreign missionary work among the Tibetans was brought to a close. The magazine China’s Millions summarized the history of Evangelical work in the Amdo region with this somber analysis:

There are perhaps 200 in the fellowship of the Church of Christ scattered throughout the eastern part of Qinghai, and though there have been a handful of conversions from Islam and Lamaistic Buddhism, there is no Muslim or Tibetan in the church today.28

Notes

1 Michael Buckley and Robert Strauss (eds), Tibet: A Travel Survival Kit (Hawthorn, Australia: Lonely Planet, 1986), p. 25.

2 E. E. Beatty, “Tibet: A Notable Observation,” China’s Millions (December 1950), p. 126.

3 Ralph R. Covell, The Liberating Gospel in China: The Christian Faith among China’s Minority Peoples (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 1995), pp. 79–80.

4 See George N. Patterson, Patterson of Tibet: Death Throes of a Nation (San Diego, CA: ProMotion Publishing, 1998), p. 383.

5 “How God Helped Save the Dalai Lama of Tibet,” Assist News Service (January 1, 2001).

6 Covell, The Liberating Gospel in China, p. 80.

7 Geoffrey T. Bull, When Iron Gates Yield (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1955), pp. 250–1.

8 See Michael Peissel, Cavaliers of Kham: The Secret War in Tibet (London: Heinemann, 1972).

9 The Dalai Lama, My Land and My People: Memoirs of the Dalai Lama of Tibet (New York: Potala Corporation, 1962), pp. 221–2.

10 Beijing Review (June 27, 1983).

11 Beatty, “Tibet: A Notable Observation,” p. 125.

12 Andrew, “The Lord’s Grace: The Establishment of Batang Church,” self-published report, no date.

13 Ralph R. Covell, “Buddhism and the Gospel among the Peoples of China,” International Journal of Frontier Missions (July 1993), p. 134.

14 John Ting with David Woodward, “Welcome the Wind (Witness of a House Church Pastor): The Secret of Survival in a Rough World,” unpublished manuscript, 1990, p. 70.

15 Ting with Woodward, “Welcome the Wind,” p. 74.

16 Ting with Woodward, “Welcome the Wind,” p. 113.

17 Ting with Woodward, “Welcome the Wind,” pp. 113–14.

18 Ting with Woodward, “Welcome the Wind,” p. 120.

19 Ting with Woodward, “Welcome the Wind,” p. 122.

20 DC Talk and The Voice of the Martyrs, Jesus Freaks: Stories of Those Who Stood for Jesus, Vol. 2 (Minneapolis, MN: Bethany House, 2002), p. 271.

21 Ting with Woodward, “Welcome the Wind,” p. 130.

22 David Woodward, “Examining a Significant Minority: Tibetan Christians,” The Tibet Journal (Winter 1991), p. 65.

23 Ting with Woodward, “Welcome the Wind,” p. 130.

24 Ting with Woodward, “Welcome the Wind,” p. 155.

25 Vanya Kewley, Tibet: Behind the Ice Curtain (London: Grafton, 1990), p. 392.

26 Leslie T. Lyall, Come Wind, Come Weather: The Present Experience of the Church in China (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1961), p. 70.

27 Paul Hattaway, Back to Jerusalem: God’s Call to the Chinese Church to Complete the Great Commission (Carlisle: Piquant, 2003), p. 10.

28 Leonard Street, “Chinghai Province,” China’s Millions (September–October 1948), p. 55.