3 ‘The Cap of Liberty’

… the impression this mountain makes is invariably glorious, and he is the unquestioned monarch of the West.

How did Frenchmans Cap come to be named? No greater mystery surrounds any Tasmanian mountain. Theories and suggestions abound, yet no evidence has been found to accurately support its provenance. An early suggestion put forward in 1829 comes from Henry Widowson’s book Present State of Van Diemen’s Land, written as a guide to prospective emigrants.

To the west, at the farthest extremity of the western tier, is an enormous, high rugged point, towering much above the rest of the other mountains; this is named the Frenchman’s Cap, from its generally being covered in snow, and bearing some resemblance to the shape of that article of dress which invariably adorns the head of a French cook.12

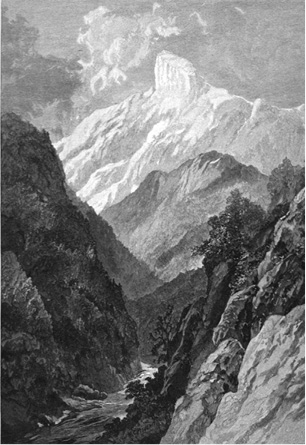

Frenchman's Cap by W. C. Piguenit, 1887 (Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office)

Frenchmans Cap was foreshortened to the inevitable ‘The Frenchman’ as early as 1840 by James Calder. Another early traveller whose curiosity was aroused was Sir Paul de Strzelecki, the Polish explorer, who spent two years exploring Van Diemen’s Land. Strzelecki wrote to Sir John Franklin specifically on the matter, and received this reply from the Governor on 25 June 1841: ‘Flinders speaks of Ben Lomond and says it was so named by Col. Patterson. I have not yet found anything satisfactory respecting the French Mans Cap [sic] —but will continue my search.’ However, nothing further was reported, and if Franklin did solve the mystery of the naming of Frenchmans Cap, he kept the secret to himself.

The following year, David Burn, a member of Sir John Franklin’s party which journeyed overland to Macquarie Harbour, may have come close to the true origin of the name when he described the sight of Frenchmans Cap from the Loddon Plains:

The cap of liberty! galling memento! erroneously [sic] said to be within view of the Macquarie Harbour bondsmen; sad source of reflection, could it have been seen and pondered by the unfortunates of that dreaded spot — surely not less unfortunate because that bondage were the merited fruit of their own delinquencies.13

Sir John Franklin’s guide, James Calder, offered his own thoughts on the matter:

From its supposed resemblance this cone bears to a helmet, the mountain, it is said, derived its name. But if so, this likeness is more fancied than real, and I have heard it compared, with greater propriety, to a common Glengarry cap.14

Any speculation on the mountain’s name depends upon the direction from which ‘the cap’ is seen. Viewed from the west, any likeness to the ‘cap’ shape is lost, as the mountain from this direction assumes a more rounded profile. Early observers would need to have seen the sheer precipice in conjunction with the curve of the western dome to arrive at the ‘cap’ shape. Author Charles Whitham, writing in the early years of the 20th Century, was unable to suggest the origin of its name, although he did offer this accurate description of the mountain from all directions:

The Frenchman is the most striking and impressive figure among Tasmanian mountains ... when you see the Frenchman from the north-east, on the Linda Track, he has the appearance of a broken column, the top shorn off at an angle resembling that of a French gendarme’s kepi, or the caps worn by soldiers of the USA Army. From the west, he looks like the dome of a locomotive, set on a mighty base. But from the south, his appearance is that of a quarter of a circle, the straight portion being the tremendous precipice on the eastern side ... From Mr Donath’s house at Crotty, the Frenchman has the aspect of a lion couchant ... but seen from all sides, and at all times of the day, the impression this mountain makes is invariably glorious, and he is the unquestioned monarch of the West.

Today it is generally accepted that Frenchmans Cap takes its name from the Phrygian headgear — the liberty cap, le bonnet rouge — worn at the time of the French Revolution (1789–1799). But the more difficult question that arises is who actually named the peak? At the close of the 18th Century, the liberty cap came to symbolise equality, brotherhood and liberty, not only in France but throughout the world. These were ideals held close to the hearts of many of the convicts and soldiers of Macquarie Harbour. They would have gazed across at Frenchmans Cap from Sarah Island and seen its sharp profile cutting the eastern skyline as they rowed their boats to and from the mainland each day.

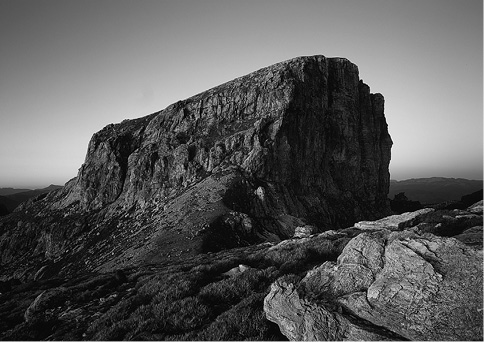

Frenchmans Cap from above South Col. (Grant Dixon)

It appears almost certain that it was from Macquarie Harbour penal settlement in 1822 that the name originated. With its similarity to the liberty cap, the peak was no doubt seen as a potent symbol representing the freedom they all so desperately craved.

For the men and women of Macquarie Harbour, Frenchmans Cap would have stood as a huge natural monument to freedom, a cherished symbol in an otherwise tortured and damnable existence. Today, no record survives to suggest who first used the name. However, it was very likely adopted through common usage among the soldiers, convicts and seamen of Macquarie Harbour, for whom it may have held more than a hint of the subversive and anti-authoritarian.

The first explorer: William Sharland journeys to Frenchmans Cap

William Sharland was the first white man to attempt to climb Frenchmans Cap. In 1823, at the age of 24, Sharland arrived in Van Diemen’s Land from England with his father and brother. The family settled on land near Hamilton. An ambitious and hard working young man, Sharland soon obtained a job with the survey department. His enthusiasm and dedication did not go unnoticed and within three years Sharland was appointed assistant surveyor.

His new boss, Surveyor General George Frankland, was keen to promote exploration in the new colony and led several important journeys himself. This frequently put him at odds with Lieutenant-Governor Arthur, who felt Frankland’s first duty lay in the more mundane task of settling the boundaries of settlers’ land grants.

Despite Arthur’s objections, and the fact that Frankland had eleven other surveyors to choose from, it was Sharland whom Frankland selected to lead the first probe west. Sharland’s instructions were straightforward enough: he was to journey west as far as Frenchmans Cap, reporting fully on the nature of the country through which he passed. The purpose of Sharland’s journey was not necessarily to climb Frenchmans Cap, desirable though that achievement might be.

The thrust of exploration in Van Diemen’s Land at this time was driven by the need to find new grazing country, and this is where Sharland’s priority lay. Frenchmans Cap merely served as a boundary, a specific landmark in the west.

On 28 February 1832, Sharland left Bothwell with a party of six men, a horse and dray and supplies for a month. The party was forced to endure 10 cheerless days of storms, driving rain and heavy snowfalls. With food running low, Sharland established a base camp a little south of today’s Derwent Bridge. He now formed a fast-moving party of three — two soldiers and himself — and pushed forward in an all-out attempt at the Cap.

Disaster was narrowly averted early on while crossing the flooded Franklin River at the foot of Mount Arrowsmith. Wading the swirling waters, one of the men lost his footing on the rocky river bed: ‘... Pierman, the soldier — a very strong, powerful man ... fortunately he recovered himself, or his fate must have been inevitable.’15 That night they camped at the foot of Mount Mullens, and moved down to the Loddon Plains next morning. Sharland decided to follow the long, ascending hump of Pickaxe Ridge, which appeared to provide a direct link with the Cap. By late afternoon the party stood above Lake Vera.

I am inclined to conclude there must be almost daily rains near the Cap, for the summit of the highest hills abound with water, standing in holes beside innumerable streams in every trifling valley ... I was surprised at looking down upon a very large pond of water, which, from its dark appearance, I judge to be very deep.

The next morning a clear blue sky filled them with optimism at climbing Frenchmans Cap. ‘Two hours, at furthest,’ Sharland confidently predicted.

We commenced ascending the hill about 7 o’clock, following up the ridge which proved very deceptive, constantly terminating in a precipitous descent, which more than once compelled us to retrace our steps. After eight hours’ incredible fatigue without a single halt, by dint of winding our knapsacks and guns up precipices and the most hazardous climbing ourselves, where one slip would have hurled us some hundreds of feet into a chasm below, we reached the long-expected height [Sharlands Peak] ... My disappointment was great when, in advancing a few steps, I discovered that ... an impassable chasm existed between us and the peak of the Cap.

What Sharland failed to realise was that Frenchmans Cap was already within his reach, had he only found the elusive connecting ridge with the rest of the Main Range, just below where he stood. After making a careful observation of the landscape, Sharland’s men marked out the letters ‘W. S.’ in rocks on the ground, then prepared to return.

After halting about half an hour, and firing a double shot at the Cap and taking a gaze at the ocean before us, we returned the same way we ascended, not being able to discover any other at all practicable. Again, we had to repeat the dangerous experiment of walking along ridges of rocks as acute as that of a house, and of lowering ourselves down the more abrupt declivities. Happily, we escaped any serious injury, except a few bruises, and returned to the preceding night’s encampment more fatigued with this day’s march than any we had before undertaken, though not exceeding in the whole, three or four miles.

Three days later the three men, hungry and tired, arrived at base camp near Lake St Clair to the welcome sight of ‘six kangaroos in the larder and a good steamer on the fire’.16 The return journey turned into something of an epic, as Sharland painstakingly followed Frankland’s instructions to the letter by exploring tracts of the countryside. When the party finally reached Sharland’s farm on the outskirts of Bothwell, they were on their last legs, their clothes torn to shreds and legs badly lacerated. ‘Could proceed no further,’ Sharland wrote, ‘my shoes being totally gone. ’

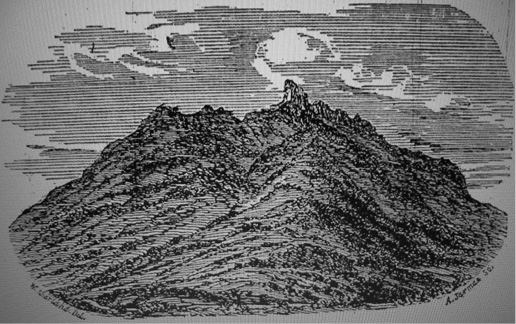

Sharland’s Frenchmans Cap, 1832. A woodcut based on an original sketch by William Sharland. (Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW)

Chris Binks, writing in Explorers of Western Tasmania, reflected on the significance of Sharland’s trip.

That Sharland had not climbed Frenchman’s Cap was not important. The additional grazing lands he found between Lake Echo and the Clarence were of value, but again were not an important outcome of the expedition. The major contribution which Sharland’s expedition made — and it was a vital one — lay in his finding a route past the King William Range and into the rich central west coast, followed by later explorers through the Collingwood and King River valleys and over the West Coast Range.17

The modern story of Frenchmans Cap really begins with William Sharland’s landmark journey. His attempt at the Cap stands as a testament to both his leadership and route-finding abilities. To have successfully plotted a course through unknown country, endured miserable weather, and come close to climbing the Cap at a first attempt, represents a significant accomplishment. Sharland’s approach to the peak by way of Pickaxe Ridge would become the accepted route to the Cap for the next eighty years. Many, like Sharland, would be frustrated in their attempts to find a way through the Main Range to Frenchmans Cap, and it would be another 21 years before the first ascent was made.

‘Britton the Bushranger’

Two years after Sharland’s journey, an intriguing report appeared in a Launceston newspaper. The newspaper reported enthusiastically that Lieutenant-Governor Arthur had been informed that a hut or hideout belonging to the bushranger Samuel Britton had been found near Frenchmans Cap. ‘This will now account for how Britton has so long eluded the vigilance of so many who have attempted to capture him,’ the Independent explained to its readers on 8 February 1834. ‘The Frenchman’s Cap, and the country around, is one of the most solitary and unfrequented parts of the island, and far distant from any settlement, so that when he obtained a good “swag”, he could retreat in perfect safety, and remain for months in his hut.’

How the hut came to be discovered and by whom is not known. It was found in a deep gully which afforded it natural protection and hid it so well that from a distance it looked nothing more than a fallen tree. The hut entrance was set low and below ground, so that its discoverers could only gain entry by crawling in on hands and knees. The hut comprised two or three good rooms, all well-stocked and furnished, and contained ‘a great quantity of clothing, one bag of sovereigns, and one of dollars’.

An unopened letter lay on the table, addressed to Britton. ‘He must, however, have had a horse at his command,’ speculated the Independent, ‘or some friend to assist him with a cart to move the provisions he stood in need of. The parties who discovered the hut left everything as they found it, keeping a strict look out; as in case Britton should make his appearance, they might be sure of taking him.’

The hut may have been located on the edge of the Frenchmans Cap region, perhaps at the foot of Mount Arrowsmith or near the King William Plains. However, it is far more likely that the hut lay hidden somewhere on the Central Plateau, perhaps at the extremity of a grazing run on the upper Derwent. In 1834 this region would have been sufficiently remote to suit Britton’s purposes.

Few landmarks were known in the west at that time and the exact location of Frenchmans Cap was still vague in many people’s minds. The hut could have been miles away from Frenchmans Cap, which was often confused with Wylds Craig, a peak further to the east. Besides, Britton’s attacks were all carried out in northern Van Diemen’s Land, around the Tamar Valley and in the Norfolk Plains area, near Longford.

Originally a farm labourer from Bristol, Samuel Britton was transported for 14 years for stealing a halfpenny. In Van Diemen’s Land his conduct deteriorated and he was finally sentenced to fifty lashes and three years at Macquarie Harbour. Upon release he appears to have turned over a new leaf when assigned to the Van Diemen’s Land Company. He worked well, cutting bush tracks for the company under surveyor Joseph Fossey, who always spoke favourably of Britton’s work. But his bad ways of the past soon returned, and between 1832 and 1835 he acquired a feared reputation as a bushranger.

Members of Britton’s gang were finally killed in a big shoot-out with police at Squeaking Point, Port Sorell. Britton himself was not present at the time of the confrontation. He had been seriously injured earlier, while the gang was making its way east from the Tamar Heads. Mysteriously, Britton’s body was never found, leading to a succession of reports of his ‘reappearance’ long after his probable death, his age at the time being about twenty-nine. No further mention was made in the press of Britton’s ‘Frenchman’s Cap’ hut.18