8 ‘The Prince of Tasmanian Explorers’

If there be an Elysium on earth, it is this.

It was not unusual for Tom Moore to push through 30 km of thick scrub in a day, carrying a heavy pack, and accompanied only by his dogs. Born in New Norfolk in 1850, Thomas Bather Moore was a sturdily built man of medium height with piercing eyes and dark complexion. His broad face was framed with a full beard, and he became a striking and commanding figure in the west for over thirty years. Moore acquired a reputation to match, both in the bush and around the towns and ‘shows’ of the west coast. Charles Whitham was in awe of his accomplishments, calling him ‘the Prince of Tasmanian Explorers’.

T. B. Moore acquired a knowledge of western Tasmania unmatched by any other. He cut tracks throughout the west and south-west, opening up large tracts of country for later prospectors. The most visible and important of these was the Linda Track, which Moore cut between Lake St Clair and the west coast, opening up the region for prospector and traveller alike. He named a number of features immediately to the west of Frenchmans Cap and many others further afield, including Mount Read and Federation Peak.

T. B. Moore, ‘Prince of Tasmanian explorers’. A 1911 photograph taken when Moore was aged about 60. (Margaret Elliston)

T. B. Moore was the consummate bushman, equally at home travelling on his own or with a party. A self-taught naturalist, his love of the bush was so complete that he never felt isolated, even when away from civilisation for months on end. Like many who worked in the bush, he enjoyed the solitude of his surroundings without ever feeling lonely. He was a self-driven man and expected much from those working beside him in the bush, and his rigid manner could lead to quarrels in his camp. Although Moore undertook only a few journeys of true exploration, his lasting contribution lay in his detailed examination of the west, where he built on the work of earlier explorers such as James Calder, James Sprent and Charles Gould.

In February 1887, T. B. Moore, then aged 36, led a party to Frenchmans Cap. Moore’s party comprised his younger brother James Moore, Walter Smith and Howard Wright. Their primary objective was to prospect parts of the West Coast Range for a New Norfolk syndicate, though this journey was particularly important for exploratory reasons. It was the first time any party had approached Frenchmans Cap from the west. As such, it established a precedent for future trips and the route they would follow. T. B. Moore’s ascent of Frenchmans Cap, regarded at the time as Tasmania’s most remote and defiant peak, would only serve to enhance his reputation as the foremost bushman of his time.

The party left from a depot south of the King River, close to where the town of Crotty would spring to life 10 years later. As they pushed forward they ‘put a match in the buttongrass and tea tree’, an unthinkable act today but a common practice among bushmen of the time to facilitate bush travel. As they moved through the country any area that showed promise for minerals was investigated. A camp would be set up and a few days devoted to prospecting, the men returning to camp each night black from head to foot from battling through burnt scrub.

The western slopes of Frenchmans Cap presented the party with a tangled mass of tea tree (Leptospermum scoparium), bauera (Bauera rubioides), cutting grass (Gahnia grandis) and horizontal scrub (Anodopetulum biglandulosum). Fire proved ineffectual against this barrier, leaving Moore’s party no choice but to laboriously hack through the entanglement by hand. It took two days to reach Frenchmans Cap from Canyon Creek, cutting through ‘bad scrub’ and crossing ‘14 creeks’ draining into the Franklin. A camp was pitched at the foot of ‘a very good spur’ leading up to Frenchmans Cap, and the party went to bed in full expectation of climbing the peak the next day.

The morning of 24 February 1887 dawned fine, and T. B. Moore’s party was climbing the spur ‘long before most people in the big cities have their eyes open’. The lower slopes needed further cutting, but higher up they emerged clear of scrub and on to clean schist and quartzite. The long ridge was topped by two peaks which Moore named prosaically ‘Knob no. 1’ and ‘Knob no. 2’, each separated by a low saddle. The higher peak was officially named Mount Moore in 2002.

The party descended to another narrow saddle, known today (informally) as West Col. Moore could now see Lake Gwendolen below them on one side (to the north), and a cluster of four small, attractive tarns on the other, while ahead rose the tower of Frenchmans Cap. The ascent proved surprisingly easy.

Having heard of the difficulties to mount this seeming obstacle, we were prepared with straps to haul each other up the cliffs, but on winding round one point of cliffy rocks, through which we found a good pass, we were very agreeably surprised to find a remarkably easy ascent could be made to the summit, not having to use our hands or straps the whole trip up.55

T. B. Moore’s party had completed the third recorded ascent of Frenchmans Cap. ‘No traces exist of anyone having climbed the heights from the westward,’ Moore noted, ‘and I may confidently assert that we are the first party from that quarter.’ Standing proudly on the summit, ‘our eyes feasted on the glories of nature’ — but for a few minutes only. A curtain of fleecy clouds drifted across the summit and the dramatic panorama was suddenly swept from view.

Moore noticed that Sprent’s trig station had partly collapsed, ‘after standing the winds and falls of snow’. He also uncovered Tully, Spong and Glover’s ‘small staff of athrotaxis [sic] placed inside a miniature cairn of stones built close to the trig station. The wood was as sound as when first placed there, just thirty years ago. On each side respectively are the names and date, carved splendidly, the edges of the letters being as sharp and clear as when first done.’56

With the summit view obscured, Moore’s party decided to do a little exploring. They made their way down the ledges of the summit slopes to the east, close to today’s summit approach and walked around to North Col. Then turning south, they followed the base of the cliffs above Lake Tahune around to East Col. By now the clouds had lifted and ‘from this point the grandest view of the day was obtained’.

All around us rose high rugged knobs, with precipitous sides, joined only to the Cap by low-lying narrow impassable spurs, which to look down upon over the cliffs would cause a weak, nervous person to shudder. To the north of us, engulfed in a deep ravine, lay a small lake [Lake Tahune]; to the south, at a less altitude were four others, in a larger basin, and from their shores rose the most majestic cliffs of overhanging rocks that I have ever seen. Bold and rugged they tower for fully 2,000 ft, and on their extreme summit is the cairn. Nothing on earth could scale them; they are grand, beautiful and sublime, and indescribable. A lover of nature gazing on this scene would exclaim with Tom Moore: ‘If there be an Elysium on earth, it is this’. Poets and artists would feast with enraptured eyes on its glories, and immortalise its splendour with pen and brush.57

Having reached their goal, Moore’s party now divided; two left the region and returned to civilisation, while Tom Moore and Walter Smith decided to linger a little longer. So impressed was Moore with Frenchmans Cap that he made plans to return to the summit early next morning. Foregoing meals for the next 24 hours, the pair bivouacked beside four small tarns below West Col, and ‘with a good old pine fire and a fine starlight night, we managed to keep warm and get a little sleep’.

Shortly after dawn next morning they were at the summit again, Moore taking bearings and making sketches of the surrounding topography. ‘Our temperaments being excited and minds elevated with the rapture of such lovely scenes, the animal desires for food were forgotten, and sorry were we to say goodbye to the old Frenchman, taking many a lingering peep at his hoary head on our way back to the camp, which we reached at 4 o’clock, and not until the scrub had hid everything from our gaze did we think something would be acceptable to eat.’

They prospected the tributaries of Ness Creek for a few days, until three days of torrential rain threatened to swamp their campsite. Desperate to reach the Franklin before floodwaters cut off their retreat, Moore had ‘even broken the old rule of no Sunday travelling’. When they arrived at the Franklin their worst fears were realised — the river was in full flood and quite impossible to cross. They now found themselves in a difficult and dangerous situation. Their supplies of food were exhausted, along with that equally important bushman’s staple, tobacco. Moore contemplated returning over the ‘frowning Frenchman’ to the Loddon Plains, but it would have entailed a long and difficult journey through unknown country, ‘a walk of fully 70 miles instead of 15 ...with only roasted wombats to eat’.

Moore solved the problem by building a raft. Logs of Huon pine were notched and bound together with straps from their knapsacks, strips of handkerchiefs and sundry items ‘generally found in the depths of a bushman’s trouser pockets’. In the end they had constructed a basic but thoroughly ‘seaworthy’ craft.

You can picture us ready for a start with our knapsacks and clothes packed on board, both of us in nature’s clothing ready, and holding one corner of the raft; I with the line of stirrup-leathers between my teeth. At a given signal, off I jumped into the stream, the nose of our craft went round beautifully, and when she was stern on to the rocky shore, Walter, with a good push, struck out manfully behind. This little piece of Scotch navigation sent us through the strongest current. The pine floated like a cork, and the resistance it gave to the rushing waters when pulling it was far less than either of us had anticipated, and we were pleasingly surprised to find on landing at the opposite bank that we had not drifted any considerable distance downstream.58

The pine raft incident is typical of Tom Moore’s resourcefulness. For every problem that confronted him in the bush he invariably sought and usually found a solution. They reached their former campsite at Canyon Creek and set up shelter just before the rain set in, a steady rain which continued for over a week. T. B. Moore’s 1887 Frenchmans Cap journey was important on a number of levels. He was the first person to report on the geology and mineral prospects of the Cap itself, and he made the first detailed observations of the flora found on the western slopes and around the summit dome. His pioneering ascent of Frenchmans Cap would have a significant effect and influence all future attempts for the next four decades. During this period every attempt but two was made from the west, leaving from Queenstown. All were following in T. B. Moore’s footsteps.

Along the Linda Track

In 1887, another party was walking to the west coast along the Linda Track, cut by T. B. Moore himself four years earlier to link Lake St Clair with the mines of Heemskirk. Led by Deputy Surveyor-General Charles Sprent (son of James Sprent), the party of eight included J. B. Walker and the landscape artist W. C. Piguenit. Of French Hugenot descent, Piguenit’s early skills enabled him to obtain the position of draughtsman with the Survey Department. By the time of this 1887 trip, however, he had resigned from the department and was devoting himself full time to painting Tasmania’s mountain regions and the landscapes of New South Wales.

Charles Sprent was an honest man and an inspirational leader, whose thoroughness and high standard of work set him apart from his peers. Many believed he was the finest administrator to head the Survey Department, and his early death from typhoid at the age of 38 (only months after completing this trip) deprived the department of a visionary leader. Charles Sprent’s close friend, James Backhouse Walker, was a prominent Hobart solicitor and historian, who jotted down a record of the party’s progress, later to be published in the book Walk to the West.59 Leaving from Hobart, the party’s intention was to complete a full circuit of the island by way of Waratah, Emu Bay (later renamed Burnie) and Launceston.

However, the main purpose of the trip was to walk the Linda Track. Passing through country completely unknown to most Tasmanians at the time, the Linda Track plunged deep into the heart of the so-called ‘lost province’. The grandeur of the scenery was revealed most dramatically when the track wound around the western face of Mount Arrowsmith (an aspect now denied traffic using the Lyell Highway). ‘Turning a corner of the descending zigzag,’ wrote J. B. Walker, ‘the enormous range of the Frenchman’s Cap, near 5,000 ft high, suddenly burst upon us in all its glory, its fantastic peaks crowned with cliffs of glistening quartzite, looking like snow but for the fact that it was the cliffs that were white …’60

The view from Mount Arrowsmith was also recorded by Charles Sprent. ‘I know of no grander sight in Tasmania than the views of Mount Gell and the Frenchman’s Cap as seen from the road descending Mount Arrowsmith.’61 The view so moved Piguenit that he immediately withdrew from Sprent’s party, remaining in the region for several days to enjoy and sketch the western landscape. From his lofty vantage point on Mount Arrowsmith, Piguenit made sketches of Mount Gell and Frenchmans Cap, which he used later as a basis for his paintings of both peaks.

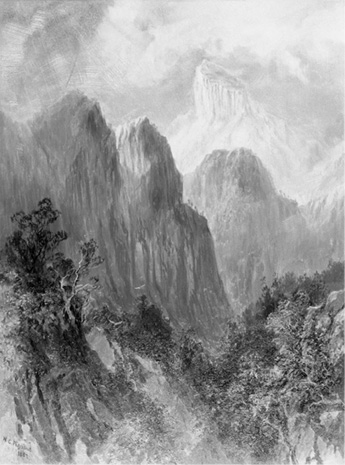

A sketch of Frenchmans Cap made by W.C. Piguenit during his ‘Walk to the West’ in 1887. (Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office)

Piguenit was no stranger to the mountain regions of Tasmania. Over the past 16 years he had made several journeys to the west and south-west, sketching scenes throughout. Today, Piguenit’s paintings of Frenchmans Cap retain their distinctive and timeless quality. Like no other images, they capture the rugged beauty of Frenchmans Cap, its rocky spire soaring majestically above the surrounding spurs and ranges. Piguenit’s paintings of Frenchmans Cap gave Tasmanians who lived in the cities their first view of a mountain that many had heard about but would probably never see.

The Linda Track defined the only practicable land route to the west coast. Funded by the government, its purpose was to provide prospectors with access to the developing west coast mineral fields. The Linda Track followed the approximate route of Calder’s 1840 track over Mount Arrowsmith, but Moore found the key link to the west through a succession of natural breaks in the ranges, following the valleys of the Franklin, Collingwood and Nelson rivers. The track finally emerged into the Linda Valley, in the heart of the West Coast Range. Light foot bridges crossed major streams, and shelter huts were provided at the Iron Store and the Wooden Store.

Coincidentally, at the same time as C. P. Sprent was leading his party along the Linda Track, T. B. Moore was standing on the summit of Frenchmans Cap, remarking that he could see his ‘track over Mount Arrowsmith very plainly and consider this is the best route that can possibly be obtained to the West Coast’. History would prove T.B. Moore correct; when the Lyell Highway was finally completed in 1932, essentially it followed the line of the Linda Track.

For the next forty years the Linda Track provided the only overland access to the west coast. It was used not only by prospectors and miners seeking access to the mineral fields, but also by tourists keen to experience this largely unknown part of Tasmania. With its spectacular mountain views, wild rivers, forests and valleys the Linda Track came to be recognised as one of Australia’s great wilderness walks. An interesting early account comes from the pen of Frances Cox. In 1890 she and her husband, Graeme, both intrepid walkers who had toured extensively overseas, undertook a walking tour around the west coast, from Devonport to the Derwent Valley. Frances Cox later wrote about their journey along the Linda Track.

There is a good suspension bridge over the Collingwood, which, having crossed, we continued our journey, now up, now downhill, until from some open highland we again got a view of the Frenchman. It is strange what an amount of personality a mountain like the Frenchman seems to possess. Just as a man with strong individuality stands out from the rest of his kind, so does the Frenchman among his fellow mountains. It is not that he overtops them in height; several equal him in this respect, but it is that he is so different from the rest that having once seen him, you never feel inclined to ask again ‘Is that the Frenchman?’ or insult him by remarking, ‘I beg your pardon; but I thought you were Mt Owen, or Mt Darwin, or some other Mt!’ Like the Matterhorn, the Frenchman is unique.62

Piners and track cutters on the Loddon Plains

Despite the enthusiasm of people such as Graeme and Frances Cox, most people, apart from the occasional prospector, were reluctant to leave the safety of the Linda Track and venture into the wild country beyond. A notable exception were the piners working the upper sections of the Jane River. From 1899 these men started packing their food and equipment across the Loddon Plains to the Jane, where good stands of Huon pine had been found.

Tragedy struck in 1901 when John Stannard, aged 19, and three companions — Jimmy Burrowes and two men named Nettle and Matthews — were collecting logs on the Jane River. They were working in a wide basin, just below two branches of the Jane River, marshalling pine logs as they drifted downstream. In the split second that the accident took place, no one actually saw what happened next. But it appears John Stannard was working his way down the trunk of a submerged tree to retrieve a wayward log when the fatal slip occurred.

The nearest man, Nettle, looked around to see Stannard struggling in water up to his head, shouting for help. Before he could be reached John Stannard was swept beneath the rushing waters. Nettle and Burrowes dived to his rescue and very nearly lost their own lives in so doing. Eventually, they retrieved the body using a pole and hook. ‘They tried and failed to restore animation,’ reported two constables who visited the site a few days after the tragedy.63

John Stannard was laid to rest in a coffin made of local King Billy pine, in an area now known as Stannard Flats. An inscribed pine board was set at the head of the grave and four Huon pine seedlings were planted at each corner. ‘The Stannard Tragedy’, published in the Mercury on 9 May 1901, broke the news to the outside world. The tragedy so affected the tight-knit community of piners that they immediately abandoned the area. ‘It was to be over thirty years before any men returned to the Jane,’ Richard Flanagan wrote in A Terrible Beauty: History of the Gordon River Country.64

Meanwhile, the onset of the west coast mining boom prompted the government to open up further tracts of land to prospectors. In early 1900, the government gave J. L. A. (James) Moore, younger brother of T. B. Moore, the task of cutting a track down the Loddon Plains towards the Gordon River.

In December 1907, surveyor Robert Thirkell re-cut and re-staked James Moore’s track for its entire length, as well as extending it southward. Thirkell also cut a deviation through Counsel Pass, down to Erebus Rivulet and along the Jane River, rejoining the 1900 track of James Moore and his own extended track at the foot of the Surveyor Range.

A measure of the extent to which it had become overgrown can be appreciated by the fact that it took Robert Thirkell four months to complete his track, even though James Moore’s track had been cut only seven years earlier. Two years after Thirkell completed his track the government, still unconvinced that the region had been thoroughly prospected, decided to open up the Frenchmans Cap region. The man they sought for the task was J. E. Philp.