9 John Ernest Philp

There is always a wild longing — a thing I cannot describe — which makes men want to go out again to wild, unknown places.

Sir Ernest Shackleton, 190865

If ever a man could feel empathy with Shackleton’s words, it was John Ernest Philp. In 1909, Shackleton, a polar hero returning from his successful Nimrod expedition, arrived at London’s Charing Cross Station to a surging crowd, a knighthood and worldwide acclaim. Back in Hobart, J. E. Philp followed Shackleton’s exploits with great interest. Like Shackleton, much of Philp’s life was torn between his love of the sea, exploration and the demands of family life. So impressed was Philp with the Antarctic explorer’s words that he wrote them boldly in blue-black ink across the opening page of his journal66 — the small ‘Collins Handy Diary 1910’ he used to record daily progress on the track he was cutting to Frenchmans Cap.67

No single person has left a greater impact on Frenchmans Cap than J. E. Philp. Much of the track he cut with great care in the early months of 1910 still forms the present route to Frenchmans Cap. From the point where Laughtons Lead joins the track up through Philps Forest, through to Lake Tahune, walkers today are essentially following in Philp’s footsteps. A few of his original blazes, now gnarled and deeply embedded in tree trunks, remain where he cut them on his way up to Barron

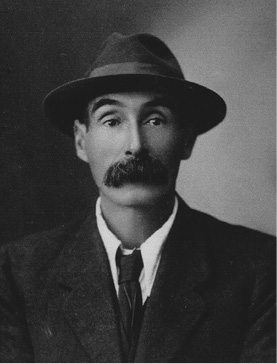

John Ernest Philp. A portrait taken about the time of his 1910 Frenchmans Cap journey.

(Anne Rood)Pass. His name continues to live on in the Frenchmans Cap landscape: Philps Lead, Philps Peak and Philps Creek.

The long-held promise of gold, minerals and timber that lay behind the decision to cut the track to Frenchmans Cap was not realised. No big discoveries were made and within Philp’s own lifetime, people began using his prospecting track for a very different purpose.

Of proud Scottish descent, J. E. Philp was born in 1869 in the small town of Franklin, overlooking the majestic sweep of the Huon River. His father, John Philp, was a master mariner and is probably the same ‘Mr Philp’ who, with ‘Mr J. Hay’, accompanied Henry Judd on a pioneering journey to Lake Pedder and to the foot of Mount Anne in 1880.68 Early photographs of J. E. Philp suggest a confident young man intent on making his way in the world. A generous handlebar moustache frames a strong face full of character, with dark inquiring eyes. He began his working life in Hobart with a firm of merchants, until a scarcity of work made him to turn to the bush for his livelihood.

J. E. Philp’s attachment to the Tasmanian bush would last all his life. He loved the natural world in all its myriad forms, from the roar of the ocean to the wind soaring up amongst the highest peaks. He could also marvel in wonder at the intricate design of a spider web spangled with early morning dew. The only creatures J. E. Philp believed had no place in nature’s kingdom were snakes, for which he held a hatred almost rivalling that of Lady Franklin, though to be fair this penchant for the destruction of snakes was common with many bushmen of the period.

In 1893, J. E. Philp worked for 15 months on the original survey for the Mount Lyell Railway, where he helped cut a path through the bush in preparation for the track layers. On his return to Hobart, Philp worked as a shipping agent for several ketches trading between Hobart, New Norfolk and the East Coast. On one voyage to the East Coast he met Vera Robinson, an attractive 16 year-old with a captivating, winsome smile who lived at Spring Bay (Triabunna). ‘Ernie’ (J. E.) Philp was immediately smitten.

Over the next two and a half years, he carried out a romantic courtship with Vera by sea, hitching a ride on trading ketches or fishing boats to the East Coast whenever he could. If no boat was available, he took the coach to Sorell, then rode to Spring Bay on horseback. The couple were eventually married in 1899, settled in Battery Point and had six children.

Vera Philp, petite and dark-haired, waited patiently at home whenever Ernie felt the call of the wild. It was Vera’s quiet understanding and strong character that provided the necessary ballast to keep the Philp family ship on an even keel whenever her husband was away.

Vera Philp and her children. (Anne Rood)

Quite early on, J. E. Philp began to feel the financial pinch of a growing family. The shipping agency provided only a modest income, and he now looked at ways of supplementing it. He turned to the only area he knew — bush work — and clearly it was not just the money that lured him. Between 1907 and 1909 he worked on two challenging bush projects in the heart of western Tasmania.

One of these projects took him deep into the Gordon River country. Here, he worked on cutting a track with the surveyor Robert Ewart, a big task that provided J. E. Philp with valuable experience. It was on this 1909 trip that Philp first struck up a close friendship with Eric ‘Dick’ Rumney. A tough and reliable bushman, Dick Rumney’s twinkling eyes and boyish fresh countenance hid an inner steely determination. A man of slim build, Rumney’s face was dominated by a broad tarbrush moustache of extraordinary luxuriance. He had roughed it in the hardest of places and over the years had tried his hand at mining, prospecting and exploring.

Dick Rumney. An early photograph taken about the time of his western exploration journeys. (Julie Rumney)

The 1909 trip was a tough undertaking that almost cost Ewart and Rumney their lives, and in the end it was only Philp’s cool head that got them through. Philp and Rumney emerged from the ordeal as good mates with a healthy respect for one another. ‘Ernie always said he [Rumney] was the finest camp mate he ever had,’ Vera Philp told Jack Thwaites years later, ‘and incidentally he had many on the reverse side, some of which should never have been in charge of a party, knowing nothing much of the bush or conducting such a venture.’69 Nine months later, Philp was offered the job of leading a track cutting party to Frenchmans Cap.

Philp’s Track

You will please proceed as soon as possible to cut and plainly mark a track to connect the Overland Track (Ouse to Linda) with the Frenchman’s Cap. The track to be selected on the easiest grade to be obtained … to be cut 4ft wide and enough work done to make it easy and practicable for foot traffic.70

J. E. Philp’s instructions were spelt out clearly by James Fincham, Engineer-In-Chief for the Department of Public Works (PWD). Fincham also directed Philp to select ‘any leading range’ towards Frenchmans Cap, observing mineral and timber prospects along the way, and to complete a diary for each day’s work. J. E. Philp fitted the job description for an early 20th Century explorer perfectly. He possessed a balanced, even temperament and knew how to bring out the best in his men. His previous experience in the field served him well, and despite having no formal qualifications as a surveyor, he acquired his surveying skills in the best learning environment of all, in the bush itself.

Philp’s was to be no random expedition. It would form part of James Fincham’s overall plan, using three separate parties, to open up that part of the country by cutting a series of tracks into the western wilderness. Philp wasted no time in making preparations for his journey to Frenchmans Cap. He bought provisions, drew equipment from the PWD store and recruited a work party. For his first choice he had to look no further than his friend Dick Rumney. He also recruited Eric Robertson, a friend of Philp’s from Spring Bay. A third man, simply referred to as ‘Lavelle’ in Philp’s diary, was probably suggested by Dick Rumney. Barely a week after receiving his instructions, Philp was ready to leave Hobart.

On 20 January 1910, Philp’s party arrived at the Franklin River. First, a depot tent was pitched to store all their provisions for the next eleven weeks. The party would need to supplement these stores by taking live game, using dogs, rifles and snares. By the end of the trip, Philp had recorded a respectable tally of five kangaroos, 10 wallabies, 11 badgers (wombats), four possums, one porcupine (echidna), four tiger cats (eastern quolls) and one native (Tasmanian) devil.

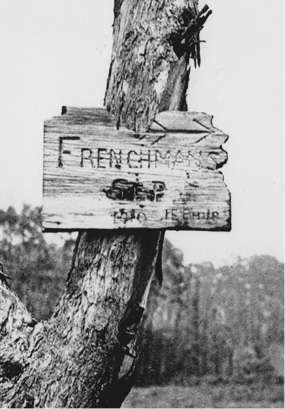

‘Philps Tree’, December 1933. Philp’s original sign points the way along Philps Lead. (Jock Turner)

Philp ignored the traditional approach along Pickaxe Ridge. He could clearly see that its steep slopes would present difficulties to heavily burdened prospectors. A better approach would have to be found. Philp found it three km south — a long finger of buttongrass (later named Philps Lead) extending west to the foot of the Main Range. Over the next five days the button grass plains were ‘fired’ and more supplies were packed in from the Franklin River depot. A new depot was established on a dry bank of Philps Creek, ‘with plenty of grass trees across the creek so we managed to get dry bedding’.

Lavelle and Robertson were given the job of clearing and staking the remainder of Philps Lead. In the meantime, Rumney and Philp climbed a long, scrubby spur up to edge of the Main Range below Philps Peak to survey the country ahead. With the impossibly deep and forested Livingston Gorge dropping away steeply below, and with Frenchmans Cap beyond, Philp could see clearly that the only practical approach lay further north, through Barron Pass.

‘Deep gorges make approach to Cap difficult,’ Philp advised James Fincham at the end of the fourth week of track work, ‘but from observations taken ahead, I consider I have chosen a satisfactory route.’71 The next six days were spent cutting and blazing a new track through the dense forest which rose above Philps Creek. ‘Country broken and rough underfoot,’ Philp noted. ‘Have pegged and blazed line thoroughly and cleared a wide track. In fact, I consider it as good if not better than any I have yet seen.’

A setback for the party occurred when Dick Rumney’s boot slipped on a moss-covered log near Philps Creek depot and he fell heavily, fracturing a rib. It was a bad fall, leaving him fit for light duties only for several days. In the tea tree forest above Rumney Plain, fires were lit to aid the cutting of the track down to a large lake at the foot of the Main Range, ‘which I have named Lake Vera, in honour of my partner’.

That night Lavelle and Robertson returned from the Franklin depot with more supplies, and just as importantly, mail. ‘Two letters from Vera,’ wrote an elated Philp. ‘My partner did not forget my bookless state and sent me three books and numerous papers. Best of all though, is the news that all are well at home. Fairly revelled in news from the outside tonight.’ The next six days were spent cutting around the western shore of Lake Vera. Another depot camp was established at its south-western end, beneath a grove of magnificent Huon pines. Warm weather made for hot work, but Philp was happy to have all the party out rather than confined to the boredom of the tents.

Broken ground and dense scrub kept him busy selecting the best route around the lake shore. ‘A fine lot of Huon pine growing along waterside and many young ones springing up,’ recorded Philp, now in good spirits and revelling in the combination of fine weather and idyllic surroundings. ‘There is a fine echo here and every axe-blow is repeated very distinctly. The reflections are very beautiful. Really a pretty scene, and one I should like to introduce to others. It is worthy of the name I have given it — Vera.’

Philp and Lavelle now pushed forward in an attempt to find a satisfactory route up to Barron Pass. This proved to be the most difficult part of the whole assignment. ‘After a stiff climb mounted a ridge and got a little closer to the Cap,’ Philp wrote after a tiring day. ‘Made a circuit of hills and returned by way of the Gap [Barron Pass] towards which I am heading. Found this pass terribly rough and scrub beggars description. Will have to try and avoid this if possible.’

It was not to be. A probing exploration eliminated all other approaches, either because of steep grades or high cliffs. Satisfied, Philp decided on the present approach to Barron Pass. ‘The grade is here in some places a trifle stiff,’ he informed James Fincham with some understatement. ‘This being unavoidable on account of broken nature of the country.’72 Another week and the party had cut a track to the top of the ‘Gap’. Philp named this feature ‘Barron Pass’, in honour of the incumbent Governor of Tasmania, Sir Harry Barron.

Early March brought returning bad weather. ‘Amused myself in afternoon in compiling a paper for amusement of the children, called the “Frenchman’s Cap News”,’ Philp wrote from his tent at Lake Vera Depot. ‘They may get some fun out of it.’ He even found time to write a poem about the lake.

LAKE VERA

Bush clad in restful tints of green

The guardian peak slopes steeply down

And fern-edged runnels creep between

The tall tree trunks straight and broad

All eager too the heights around

Reach down to woo their mountain bride

And with a kiss that knows no sound

Rest mirrored on its bosom tide

Despite his relaxed mood, Philp was aware of other problems he now faced, besides the weather. Up in the high country game was scarce and their supplies were running very low. ‘Are getting on short commons in food line,’ Philp noted in his diary. ‘Sugar is expended. Butter is done and we have little bacon left here …’

There were other problems for the party, too. Seven weeks of isolation in the bush was beginning to tell. ‘Lavelle getting disagreeable and eager to get away,’ Philp recorded with the concern of a leader anxious to maintain a cohesive party. ‘He cannot stand exile from a city for long and novelty has gone.’ Heavy rain, hail and snow again kept them tent-bound, and the level of Lake Vera began to rise noticeably.

Valuable work days were being lost as the men lay about listlessly in the tents. Food supplies were almost exhausted. ‘Last night very cold,’ wrote Philp. ‘Woke this morning just after midnight with feet like stones … All hands in camp all day and growling at the restraint.’ By the tenth of March, conditions had eased enough for work to resume. They were now working on the section of the track north of Barron Pass, below the soaring cliff faces of Sharlands Peak and Nicoles Needle.

‘From the pass the track has, perforce, to follow along base of cliffs and over stony country— with stunted, stiff mountain scrub, difficult to negotiate and cut,’ Philp noted. ‘Made good headway despite unfavourable conditions. Hail lay on ground all day.’

The party pushed ahead beyond Artichoke Valley, a feature which Philp believed to have been the bed of a small lake at one time. While the rest of the party worked on the track, Eric Robertson doubled back to the Franklin for desperately needed supplies, returning after a long day at 8.30 p.m. The party now drew ever closer to Frenchmans Cap, but the long haul up and down Barron Pass from Lake Vera depot still had to be made each day.

By the middle of March, bitterly cold weather had set in. However, the end was now in sight, with the dome of the Cap looming large before them as they cut forward. ‘At the foot of saddle leading to Cap there is a pretty lake; we climbed to top of saddle [North Col] which is a razor-backed ridge, snow swept and very steep. Found it difficult to make ascent of Cap in our limited time and without a rope.’

Philp named the ‘pretty lake’ Lake Tahune, possibly an oblique reference to ‘Tahune Linah’ (an Aboriginal name for Huon River), a nom-de-plume he used when writing articles for the Tasmanian Mail.73 If so, it would be the closest Philp ever came to naming a feature in the region after himself. Late on the afternoon of 15 March 1910, in cold and fog, the cutting of the track to Frenchmans Cap was finally completed.

An original tree blaze cut by J.E. Philp in 1910 on the way up to Barron Pass. (Martin Walch)

It was undoubtedly a first-class job, but back at Lake Vera depot the party was hardly in a celebratory mood. Everyone was tired after ‘a very stiff day out’. Besides, there was still much work to be done packing up and collecting gear on the way out ‘adding to our weight materially and we found we each had quite enough to carry’. The township of Ouse was still a long way off, food was running low and the dogs were badly in need of food.

We baked last flour tonight — a small loaf at that. For the past fortnight or more we have lived on bacon and bread and bacon fat, with an occasional [badger] soup. Game very scarce. We have no sugar and oatmeal is nearly done, much to disgust of party … my birthday [today] — the third one I have spent in the bush. Was the recipient of good wishes from the party. When I remembered it we were on the track ‘homeward bound’.

Eight days after his return to Hobart Philp submitted his report. Inexplicably, it failed to generate any enthusiasm or support at departmental level. Despite his having drawn up a detailed map of Frenchmans Cap, nothing further was done to promote use of the new track. It was completely forgotten for the next twenty-three years.

There is no doubt that the track was used by prospectors for a few years (in 1932, Davern and Anderson found a discarded prospector’s shovel beside the shore at Lake Tahune). Prospectors, however, were interested in discovering minerals, not writing about their trips. They rarely recorded details of their experiences in the field. Within a very few years, overgrowth obliterated the point where Philp’s Track left the Linda Track.

‘The strange thing is that the government apparently lost all trace of the track they paid for,’ Philp informed Fred Smithies many years later, ‘though they had two reports, plan and diary of daily doings — besides intermediate correspondence.’ Twelve months after the track had been cut the Mines Department, embarrassingly, had to contact Philp ‘asking for a loan of my plan as they had mislaid their copy’.74

Philp’s track was unknown to the first bushwalkers who tried to penetrate the region. Only in the 1930s did Philp’s work finally come to the attention of a handful of bushwalkers. In 1934, J. E. Philp replied to a letter from Fred Smithies.

I am sending you all the papers I have kept in connection with the [Frenchmans] job. Will you please take particular care of them, as I value them for association of some very pleasant days. I was out on that part of the country for three summers in succession and so have a diverse knowledge of it ... It is indeed gratifying to me to learn that my work has stood the test of 23 years. Davern says the stakes stand up like a picket fence, and in the big timbered country the track is as open as a street.75

J. E. Philp was one of the last of his kind — the bushman explorer — and his life overlapped the age of the recreational walker. He lived just long enough to see its dawn. ‘A number of parties have, in the past couple of years, used the track and scaled the mountain,’ he wrote in 1937, five months before his death. ‘Possibly in the near future accommodation huts will be erected, and this so long unknown and unvisited Monarch of the West will be taken in the regular round of tourist mountaineers.’76

J. E. Philp’s predictions rang true; four years after his death the Frenchman’s Cap National Park was declared. Philp cut his Frenchmans Cap track to ensure it would last for decades. In 1910 neither Philp nor the government could have suspected that the track would eventually attract tourists from all over the world. Today it stands as a tribute to J. E. Philp. Given his profound love of the bush, he could have wished for no better memorial.