10 Along the Crotty Track

The men working on the track are all skilled tradesmen, expert bushmen, and their knowledge of camp pitching can only have come of long experience.

Soon after J. E. Philp completed his work, plans were made to drive another track in from the west. This was to allow prospectors to access Frenchmans Cap from the Queenstown side. Neither track served this intended purpose for long. Philp’s track suffered the worst. After 1910, the only formal mention of the track comes from a Mines Department letter of 1929, which simply described the track as ‘impassable.’77

The Crotty Track fared somewhat better. It began from the Crotty Smelters Junction on the North Lyell Railway. It is easy to see why Philp’s track quickly fell into disuse. The Crotty Track was by far the better alternative for prospectors making for Frenchmans Cap. The track could be reached easily from Queenstown by rail, and the track itself was well-maintained, at least for the first few years. The beginning of the Crotty Track was marked with a sign, ‘Track to the Frenchman Cap’ [sic].

‘On the track to the Frenchman.’ A rare photograph of the Crotty Track as it appeared in January 1915. (Tasmanian Mail)

The track took its name from the former smelter town of Crotty whose meteoric rise over six short years was only exceeded by its rapid decline into oblivion. Crotty had become the victim of mining company politics when, almost without warning, the North Lyell Mining Company amalgamated with the Mount Lyell Company. Everything was moved to Queenstown and Crotty became a ghost town. Once busy streets had been reduced to a few posts, a chimney stack or two and assorted pieces of twisted and rusting iron.

Meston and de Bomford

A short time after the Crotty Track was completed — possibly only days — Frenchmans Cap was climbed by two Queenstown men, A. L. Meston and Edwin F. S. de Bomford. For the two men it was probably a memorable adventure, but historically it marked the first ascent of Frenchmans Cap for purely recreational reasons. All previous ascents had been linked to either survey work or the search for land, minerals and timber.

Arch Meston was born in 1890 of Scottish descent. Educated at Launceston, he was an outgoing, generous and at times unconventional character who excelled at sport and athletics. Aged 23, Meston had been appointed to Queenstown in the first years of a long and distinguished teaching career. ‘He walked alone, or with one companion,’ an acquaintance recalled years later. ‘He plotted his route by the look of the skyline, considering his privacy outraged if another boot-print appeared on the mountain. He inevitably carried a book in his rucksack.’78

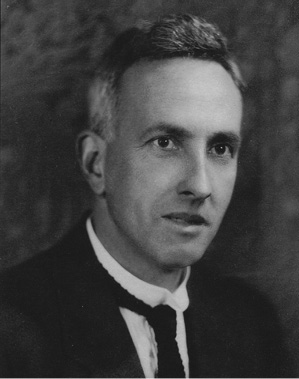

A. L. Meston — an early Frenchmans bushwalker. (Peggy Ross)

Meston’s companion, Edwin de Bomford, was born near Triabunna in 1861. Years earlier, Edwin and his brother walked the Linda Track to Queenstown looking for work in the wake of a sudden downturn in family fortunes.79 Edwin worked hard and eventually became chief boilermaker at the Mount Lyell mine. Although aged 51, he proved himself a fit and enthusiastic companion to the younger Meston.

The new track made the journey a straight-forward one, although for some reason they decided not to follow, or missed, the blazes that led beyond Lake Gwendolen up to North Col. Instead, they tackled the steep slopes beside the lake and gained the ridge topped by Mount Moore which had provided T. B. Moore’s party with an easy ascent 26 years earlier.

‘I infer that my trip in March 1913 was in the final stages by the same route as his [T. B. Moore’s],’ Meston wrote in reply to a letter from Fred Smithies in 1931. ‘We found none of the difficulties of the last part of the ascent that you did. Did you climb by the spur north of the Cap [North Col], the one he [T. B. Moore] mentions as marked by “small heaps of stones”? My recollection of the mountain is quite vivid but I cannot place the narrow pathway along the cliff face that you worked along. It is obvious that you followed a different route to me.’80

Meston’s brief letter to Fred Smithies is the only record of their 1913 ascent. In later life Fred Smithies would describe Arch Meston as ‘a great walker in our western areas, but a very silent one; he did not talk much about his travels’.81 Despite the close-knit Queenstown community, Charles Whitham had no knowledge of Meston and de Bomford’s ascent when his party visited Frenchmans Cap 12 months later.

Meston went on to become a superintendent in the Education Department and a keen historian. His most enduring contribution is his carefully researched work on the Van Diemen’s Land Company. He also acquired a sound knowledge of Tasmanian colonial history and the culture of the Tasmanian Aboriginal people. He was the driving force behind the proclamation of the Cradle Mountain-Lake St Clair National Park and became its first board chairman.

While painstaking in recording information for his research trips, Meston appears to have been almost dismissive of the importance of his own journeys. In more recent times, a tangible reminder of his 1913 Frenchmans Cap trip came to light. Pressed between the pages of an album of his newspaper cuttings, his daughter came across a sprig of small flowers — small white immortelles and blue gentians — beside which Meston had written, ‘From the summit of Frenchman’s Cap’.82 While this 1913 journey was to be Arch Meston’s only visit to Frenchmans Cap, Edwin de Bomford’s fascination with the mountain had only just begun.

Charles Whitham

Work began on the Crotty Track in early 1912. It was completed 12 months later but not before Charles Whitham had walked half its length. As Chairman of the Mount Lyell Tourist Association in Queenstown, Whitham was a strong advocate for the Crotty Track. From the summit of Mount Fincham, Charles obtained a full view of the wild, broken nature of the country surrounding Frenchmans Cap.

To the west there is a magnificent panorama, bounded by the West Coast Range … the view to the east of Fincham is closed by the giant bulk of the Frenchman … The prospects from our Western mountain tops may be monotonous to those who have neither eyes to see nor souls to appreciate, but to fit minds there is a deep fascination in the delicacy and soft loveliness of the shades in our forests, skies and hillsides on a misty day. The morning was dull, but not wet, and there was a strong breeze which swept the tops of the lower mountains, but left the Frenchman’s head wrapped in cloud. Directly beneath us to the windward was a button grass plain, a West Coast plain, and, as a passing beam of sunlight swept across it, the effect was like the rolling of a golden carpet across a brown floor. Above us two hawks were circling, and a long way below a flock of white cockatoos flew out of the scrub.83

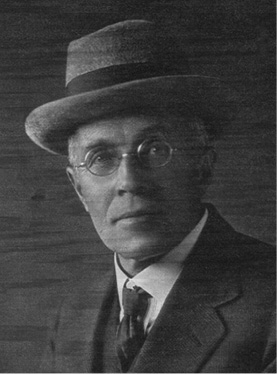

Charles Whitham. A formal photograph taken around the time of his 1914 journey to Frenchmans Cap. (Whitham family collection)

For Charles Whitham the prospect of reaching Frenchmans Cap was now feasible. ‘When the track is made to the Franklin, the river will be reached in about four hours from Crotty, and it should be possible to attain the summit of the Frenchman and return in two days. Who knows what secrets it may hold?’ For Charles Whitham, that question would be answered over the next 17 months.

‘Leaving the train crowded with merry picnic parties, we humped our swags and sped eastwards along the undulating track,’ Charles Whitham informed readers of the Zeehan and Dundas Herald. ‘It was nearly midnight before we turned in, and we were up at five in the morning in order to make an early start for the attack on the great mountain.’84

Charles Whitham is a leading player in the modern story of Frenchmans Cap. This is all the more remarkable for his having visited the mountain only once during a rushed trip in February, 1914. He was one of the very first to write in detail about the mountain, employing a descriptive quality that has never been equalled.

The Frenchman is the monarch of the south-west; no matter where you see him from, he dominates the landscape … I have seen him in dark purple velvet, and half an hour afterwards, under the sunshine, in virginal white. He is set as a dome on many branching buttresses…and there are eight lakes concealed beneath his mighty shadow … It is the quality of milky whiteness and purity that somehow invests the giant bulk of the Frenchman with an atmosphere of grace and lightness. If one could spend a night on the knees of the monarch, beside those quiet lakes, and watch the moon gradually light up the regal symmetry of the marble heights, the scene would form a vision of sublimity to remain in the mind for evermore. Even in the garish daylight, the cliffs are the noblest of nature to be seen in Tasmania … He differs strikingly from all his peers in colour … the Frenchman is of pure white quartzite, call it marble if you will.

Charles Whitham was born in 1873 in India, where his father served in the British Army. In 1886, the family emigrated and set up a small farm in northern Tasmania. Charles obtained a clerical position in Hobart, eventually moving to Queenstown where he worked as traffic clerk with the Mount Lyell Mining and Railway Company. Charles was an intelligent, articulate and perceptive man, a true lover of the natural world.

His interests were many and varied, but above all he held a particular passion for literature. ‘Then, as now, I was a bookworm,’ Charles wrote, ‘and spent a great deal of my life in the Public Library. I took up Latin, mathematics, book keeping, and piano playing, but dropped them all after picking up a smattering of each subject. Next to literature, I was fond of explorations in the bush.’85

He is best remembered for his book Western Tasmania: A Land of Riches and Beauty, first published in 1923 and still in print today. He also wrote a number of colourful newspaper articles describing his excursions into the mountains, bush and townships of western Tasmania. These articles have recently been published in book form as Rambles in Western Tasmania. His 1914 journey to Frenchmans Cap, however, remains the pinnacle of his exploratory forays.

‘The finest trip to be taken on the west coast by those who are fond of adventurous climbing is to the Frenchman’s Cap,’ explained Whitham, ‘but the expedition occupies at least three days, and can only be undertaken by those who are of robust constitution … Five or six parties from Queenstown have gone out, but the list of persons who have ascended the Frenchman is a very small one, and it does not include any women.’86

Charles Whitham’s party was made up of fellow employees of the Mount Lyell Mining and Railway Company. Robert Eyes was a locomotive superintendent and a good friend of Whitham; Leslie Coulter and Edwin Barkley worked at the mine as assistant engineers. Charles was aged 41 at the time of the journey and Robert Eyes was about the same age, but Coulter and Barkley were both 20 years their junior.

‘I fancy the description of a trip, or rather expedition, we had last week will interest you,’ Leslie Coulter wrote to his sister in Ballarat. ‘Well, there is a very inaccessible mountain and one of the highest in Tasmania named Frenchman’s Cap, so called on account of its appearance from the ‘Overland’ to Hobart — a soldier’s or gendarme’s cap, without the cockade. Recently, the government cut a track and erected a hut with a ‘cache’ some distance from the foot, so two Queenstown fellows, Whitham and Eyes — both of the Railway Department — and Barkley and myself made a trip out there.’87

Leslie Coulter was a promising 21 year-old engineer and a graduate of the Ballarat School of Mines. Two years earlier, he came to the attention of the directors of Mount Lyell when he pulled a number of miners from certain death at the 1912 Mount Lyell Mine Disaster. He received a gold medal from the Mount Lyell Company for his bravery. The self-effacing Coulter was a reluctant hero. ‘I went down and got the fellows up,’ he informed his mother and family. ‘It was nothing in particular, but if a word of this ever gets public I should never forgive you all.’88

Leaving the hut beside the Franklin in the early morning twilight, the party climbed up to Lake Gwendolen. Charles explains:

Turning a sharp angle, we came suddenly upon a striking and magnificent view, foretaste of the still greater glories to follow. Right ahead is the final summit, still 1,000 ft above us, and from it descends a sheer wall of lucid stone to the head of a quiet lake. This little lake is pear-shaped, measuring about 300 yards by 200. Mr T. B. Moore, prince of Tasmanian explorers, has laid it down that all Western lakes must have feminine names to suit their capricious loveliness, and where Mr Moore has led humbler men should be content to follow. Unless he has already christened this magnificent mountain tarn, we name it Lake Gwendolen.

The party had lunch at the lake, beneath the huge dome of Frenchmans Cap. The weather now opened up to a sunny day that grew warmer by the minute. ‘Withal, our two younger members, with the careless audacity of youth, were soon stripped, and plunged red hot into the alpine pool.’

The climb up from the river had left Charles with a badly strained hip. ‘At the lakeside the writer of these notes was compelled to rest a strained hip,’ Charles admitted, ‘and the remainder of the ascent was made by only three.’

It must have been a bitter disappointment. For years Charles had studied and admired the majestic profile of Frenchmans Cap from a distance, read of T. B. Moore’s exploits on the mountain, and probed its approaches along the Crotty Track in 1912. Now, after much careful planning, he was denied the ultimate satisfaction of reaching the summit — on the very threshold of success. Eyes, Coulter and Barkley now pressed on for the summit.

‘The climb then commenced,’ wrote Leslie Coulter, ‘2,000 ft from the lake thro’ dead scrub, the most efficient entanglement known — it tore us to pieces. When we got above the scrub and on to a ridge, we found another lake on the other side, about 1,000 ft below us [Lake Tahune].’ From the North Col, the summit party tackled the rock buttress directly in front of them, ‘a steep rock ascent, difficult in places, but not dangerous for any man with a clear head’.

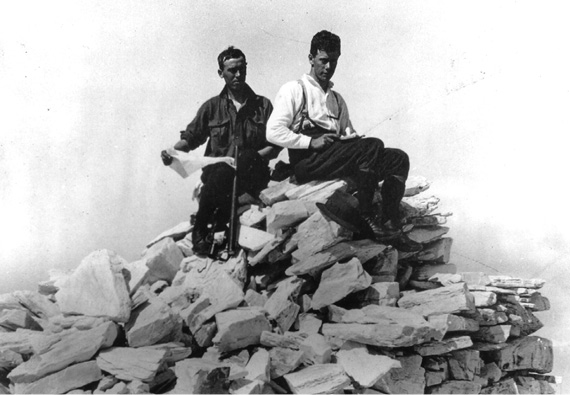

Scrambling over rock ledges, they finally reached the summit at 2.30 p.m., where ‘an hour’s rest was taken — a crowded hour of glorious ecstasy’. The ‘torrid summer’s day’ (they recorded a summit temperature of 32 degrees C) also brought ‘those obscene creatures, the March flies’. Robert Eyes photographed Coulter and Barkley on the summit cairn, the earliest known photograph of a party on the summit of Frenchmans Cap. ‘We proceeded to identify the mountains of Tasmania with a compass and maps,’ explained Leslie Coulter. ‘It was a most magnificent view … immediately below us with a sheer drop of about 1,500 to 2,000 ft were four more lakes, which, being un-named, we egotistically named after our own noble selves, and recorded the fact with a sketch in a bottle which we put in a cairn.’ (Charles later renamed these four valley lakes.)

Early summiteers. Two members of Charles Whitham’s party, Leslie Coulter (left) and Edwin Barkley, rest on James Sprent’s summit cairn, February 1914. This is the first known photograph taken on the summit of Frenchmans Cap. (Rachel Biven)

Meanwhile, nursing his strained hip back at Lake Gwendolen, Charles made the most of his enforced convalescence to luxuriate in his surroundings. He closely observed the geology and composition of the gigantic flanks of Frenchmans Cap soaring above him, and admired the pristine beauty of Lake Gwendolen.

It is shallow at the edges, with sharp pebbles of pure white stone, but is very deep in the centre, and its waters are of a marvellous translucency. Most of our Western streams and lakes are of an amber colour, from the peaty soil of the surrounding country, but the waters of Lake Gwendolen come straight off the milky rocks, and are of incredible crystal purity.

With the ascent accomplished, the party set off for the hut beside the Franklin, arriving at last light. The next morning, ‘we had to make our way back to the railway line which we reached at 9.30 a.m., after an absence of only 40 hours, and by the afternoon we had resumed the comparative ease of our ordinary toil.’

Ten days later, Charles Whitham’s article ‘Four to the Frenchman’ appeared in the Zeehan and Dundas Herald. It was an important contribution to the knowledge of western Tasmania at the time. Most west coasters had seen Frenchmans Cap from a distance, but knew virtually nothing about the mountain and the country that surrounded it. Charles Whitham was responsible for naming eight lakes at Frenchmans Cap. With his penchant for verse, Charles selected names for the four valley lakes from D. G. Rossetti’s poem ‘The Blessed Damozel’, verse xviii.

‘We two,’ she said, ‘will seek the groves

Where the lady Mary is,

With her five handmaidens, whose names

Are five sweet symphonies,

Cecily, Gertrude, Magdalen,

Margaret and Rosalys.’

Charles substituted Lake Millicent for Margaret, as the latter had been already been given to Lake Margaret in the West Coast Range by T. B. Moore. In 1934, Jack Thwaites renamed Lake Rosalys as Lake Sophie, unaware of Charles’s earlier naming. Charles also named Lakes Gwendolen, Nancy, Clara and Winifred, though the names of the last two have not survived to the present day (see Frenchmans Cap Nomenclature, Appendix I).

Charles Whitham was a man of great vision endowed with a love and appreciation of Frenchmans Cap which endures to the present through his writings. Every visitor who refers to a map of the region feels his impact, and his contribution to opening up the region cannot be overstated. Elsewhere in western Tasmania his name is commemorated in Whitham Falls, Whitham Bluff and Whitham Fault. At Frenchmans Cap, Lake Whitham lies nestled below the quartzite slopes of Philps Peak in the Main Range. Hidden from view, it escaped being named by Charles when his party visited the region in 1914. Even today this lake receives few visitors. It was left to a later generation to name this picturesque lake for the man who made such an important and lasting contribution to Frenchmans Cap.

Frenchmans Cap and North Col, seen from the west. (Simon Kleinig)