11 More Ascents from the West

Taking advantage of the exceptional weather this Easter, a party started for a three day’s trip to the Frenchman’s Cap.

The second decade of the 20th Century really saw Frenchmans Cap come of age as a mountain destination. For the first time the peak was now within reach of the fit recreational walker. Such was the nature of the undertaking, however, that only an adventurous few ever accepted the challenge. Those that did invariably started their journeys from Queenstown. Edwin de Bomford (who had climbed Frenchmans Cap with Arch Meston in 1913) felt compelled to repeat the experience and returned to the mountain in early 1915.

One of Edwin’s workmates at Mount Lyell was a young electrical engineer named Harold Cornell. A graduate of the Ballarat School of Mines, Harold Cornell, like Leslie Coulter, had moved to Queenstown to broaden his experience. He became good friends with Edwin and his welcoming family. Harold fell in love with Edwin’s elder daughter, Millie, and in 1916 the two were married.

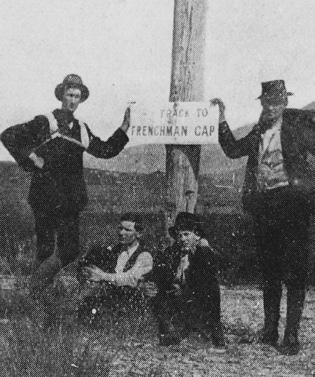

On the Wallaby Track. A Queenstown party at the start of the Crotty Track, Easter 1915. Left—Harry Payne, Harold Cornell, Roland Machin, Edwin de Bomford. (Weekly Courier)

Edwin also invited two other men to join his party: Harry Payne and Roland Machin, the latter an 18-year-old fitter at Mount Lyell. Edwin planned their trip for the Easter of 1915.

‘Taking advantage of the exceptional weather this Easter’, Edwin wrote in the Weekly Courier, ‘a party started for a three day’s trip to the Frenchman’s Cap, distant about 65 miles.’89 The party left Queenstown at 6.00 a.m. and journeyed by rail to the start of the Crotty Track. ‘We fell in with an old prospector, who extended the usual West Coast hospitality, and while the billy was boiling kept us interested with stories of the early days of Mount Lyell.’ After a meal the party ‘bade our friend good-bye’ and set off along the Crotty Track for the hut at the Franklin River, which they reached at 7.00 p.m.

After tea we made ourselves comfortable for the night. We left camp on Sunday morning at 8.30, arriving, after a stiff climb, on the summit at 3.00 p.m. We were well repaid for our climb by the wonderful view we obtained of the surrounding country. What struck us most was a cleft on the inside of the Cap, almost perpendicular, with a clear drop of fully 1,000 ft. At the foot we could see a chain of small lakes. We stayed an hour, took several photographs, and reached camp at 8.00 p.m., and got home on Monday ... From a tourist’s point of view the trip is really the finest on the West Coast.

Edwin de Bomford’s photographs show the party beside the sign at the start of the Crotty Track, carrying swags and dressed in familiar bush attire of the period; hats, old jackets with waistcoats and boots topped with cloth puttees, clothing that would characterise Tasmanian bushwalkers for the next 30 years.

de Bomford’s return

Edwin de Bomford returned to Frenchmans Cap for a final time in December, 1915. This time he took in a party of five enthusiastic teenagers who had already climbed a number of peaks in the West Coast Range. In 1917, a stoppered bottle containing their names was found on the summit of Mount Huxley by Charles Whitham.90 Edwin’s elder son, Ted de Bomford, Lynton Payne, Teddy Deegan, a youth named Slater, and another (who remains nameless) made up the party. Of particular interest was the inclusion of 11 year-old Teddy Deegan, the youngest person to climb Frenchmans Cap up to that time, and a claim he probably held for many years.

The party travelled on the midnight train from Linda to the start of the Crotty Track. They shared the centre compartment, crowded with a colourful collection of noisy passengers: miners in celebratory Christmas spirit, chatty tourists, happy children and tired mothers with armfuls of Christmas packages.

Edwin’s party caught the attention of Charles Whitham, who was travelling with three companions to Lake Jukes over the Christmas break. Charles described them as ‘five clean, husky Queenstown lads with one elder, staunch as the boys. These had compact swags, and were setting out on the big trip to the Frenchman’s Cap, monarch of Western Mountains.’91

Few details survive from this trip. Edwin de Bomford probably led the party along the route taken by Arch Meston and himself in 1913. Edwin remembered the boys laughed at his inclusion of porridge in their daily rations, only to devour it with relish throughout the trip.

Edwin de Bomford, the ageing stalwart who had made Frenchmans Cap his own for a few years and introduced the peak to many others, left Queenstown around 1918. During World War One his close friend and son-in-law, Harold Cornell, was killed near Albert on the Somme in France. At the end of the war Edwin moved to Hobart to support his widowed daughter, and to help in the running of the family apricot orchard at Geilston Bay. Edwin de Bomford died in 1954, aged 93.92

The war also took its toll on other early Frenchmans Cap summiteers. Harold Cornell’s friend Roland Machin, who climbed the peak with him in 1915, became a flying officer and joined Harold’s unit, the Australian Flying Corps, forerunner of the Royal Australian Air Force. He also died in action on the Somme in France.

Leslie Coulter, a member of Charles Whitham’s 1914 party, found that his experience as an engineer at Mount Lyell led him into service with the newly-formed Australian Mining Corps. The unit used its collective knowledge of geology, drawn from engineers and miners amongst its ranks, to determine where best to construct trenches and dugouts, and, importantly, where to locate drinking water. It used a system of tunnels to penetrate enemy positions and lay charges.

Leslie Coulter’s DSO, presented to him by King George V at Buckingham Palace, 1917. (Simon Kleinig)

Leslie Coulter served as company commander with the 3rd Tunnelling Company. Many of the men in his company had worked with him at Mount Lyell. Coulter rose to the rank of Major, and was involved in operations south of the town of Béthune, in northern France. His unit also went into action around the town of Fromelles, where Australia suffered the highest number of casualties in its military history. The Australian War Memorial goes even further, describing the battle as ‘the worst 24 hours in Australia’s entire history.’

Leslie Coulter, daring and fearless, was eventually wounded in action while successfully completing a mission during which he displayed considerable gallantry. After recovering in hospital from gunshot wounds, he was invested with the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) by King George V at Buckingham Palace.

Leslie returned to the Western Front from leave and on the same day was shot dead by a sniper in the trenches during an attack on Hill 70 in northern France in 1917. ‘He was all the time right up in the front of us all, with a bright and cheery word for all,’ Sergeant Boyes wrote to his wife in Queenstown. Boyes was one of the trapped miners whom Leslie had pulled to safety in the 1912 Mount Lyell Mine Disaster. ‘A sniper got him, and I think he never suffered. We took the trench, but we lost our Major. At any rate, I shall never forget him. It just breaks my heart to know that he has gone forever.’93

‘I shall never forget the simple impressive funeral service and the faces of those brave rugged-cheeked miners who loved him so,’ wrote Leslie’s Commanding Officer, T. W. Edgworth David. ‘Very tenderly they bore the coffin between the two long ranks of all the men of the company who could be spared from action ... When the simple service was over all passed with bared heads around the grave and then silently drew off in little groups. Our hearts were very full.’94

Leslie Coulter was aged 26.

The burden of World War One (1914–1918) weighed heavily on the shoulders of Tasmanian servicemen and their families. The cold statistics reveal more than 2,500 Tasmanians died in that terrible conflict. There was a Tasmanian casualty for every day of the war, a big sacrifice to impose upon a state which had a population of less than 173,000 at that time. The long lists of names on Honour Rolls fail to convey the unbearable grief, now long forgotten, that was borne by the families of the fallen, not to mention the loss to the wider community of such rich, unfulfilled human potential.

In need of repair

The interruption of World War One hampered further attempts at Frenchmans Cap. The Crotty Track began to fall into disrepair. ‘It was last repaired in 1916,’ Charles Whitham informed the Department of Public Works in a letter dated 25 April 1919. ‘There are a great many trees across the track, and in some parts it is quite overgrown.’95

Whitham’s request for repairs to be carried out was rejected as being ‘principally in the interests of rare tourists and mountain climbers’. By the mid-1920s, the Crotty Track was in a sorry state. ‘I tried to do this trip with a party three years ago,’ Bernard Brooker wrote to the government in 1929, ‘but had to turn back owing to the density of the scrub, and I may say it takes some scrub to stop me.’96

However, the death knell for the Crotty Track really came with the opening of the new West Coast Road in 1932. Of the two tracks providing access to Frenchmans Cap, Philp’s Track was far more accessible to west-bound traffic, and more scenic.

For a short time the Crotty Track opened up an important corridor to Frenchmans Cap. It allowed a handful of resourceful people to prospect, to log pine and to stand on the summit of Frenchmans Cap. But with the Crotty Track now impossibly overgrown, Frenchmans Cap again receded into the realm of the mysterious and the unknown. Any suggestion of climbing the peak was regarded as a reckless undertaking.

‘The Bushrangers’ attempt Frenchmans Cap from the east

The years after World War One saw the opening up of many wilderness areas in Tasmania. Up to that time, tourist activities, including bushwalking, were confined to districts served by the railway or that could be reached on foot. The motor car changed all that. Now it was possible to reach wilderness areas that most people had only read or dreamed about.

In the first months of 1920, two groups of friends from Launceston used motor cars to rendezvous by the shores of Lake St Clair. At that time Lake St Clair was a remote destination. Just to reach the lake required a jolting journey along a rough track scarcely suited to vehicular traffic. Charles Monds, Ray McClinton and Fred Smithies set up a comfortable camp beside the lake for the next three weeks. They toured the lake by boat, climbed Mount Olympus and captured scenes around the lake shore in scores of photographs.97

In early February, the second party arrived at Cynthia Bay. Dubbed ‘the Bushrangers’ by their lakeside friends, George Perrin, Syd Yard and Stephen Spurling were on the first leg of a journey to Frenchmans Cap. George Perrin was a Launceston businessman who operated a retail department store, Perrins Pty Ltd. George Perrin was no stranger to the bush. He and his wife, Florence, had earned quite a reputation as enthusiastic bushwalkers and skiers. In 1916, the Perrins made a traverse of the Pelion Range to its western extremity, Perrins Bluff, named after them by their guide, Paddy Hartnett. Their elder daughter, Jean, married Fred Smithies in 1930.

‘The Bushrangers’ leave Lake St Clair for Frenchmans Cap, February 1920. Left— George Perrin, Syd Yard and Steve Spurling. (Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery)

Steve Spurling was the third in a dynasty of Spurlings who left a strong impression on early Tasmanian photography. It was Stephen Spurling III who helped pioneer photography in Tasmania’s wilderness areas, travelling extensively throughout the state. He made a pioneering trip to Cradle Mountain in 1905, naming several features, and was amongst the earliest photographers of the Gordon River. He took what were probably the first images of the Franklin River, along with many other photographic ‘firsts’. Spurling’s contribution to raising the level of public awareness of the value of wilderness in Australia is significant. Syd Yard remains very much the mystery man of the party. All that is known is that he was born at Lefroy near George Town in 1889 and appears to have been both an employee and trusted friend of George Perrin. Steve Spurling referred to him simply as ‘George Perrin’s man’.

Any attempt to reach Frenchmans Cap in 1920 was an adventurous undertaking. Access to the mountain had become very difficult. Both the Crotty and Linda tracks were now overgrown and Philp’s track had been forgotten. While there were numerous ascents from the Queenstown side, there is no record of anyone having attempted to climb Frenchmans Cap from the east since Tully, Spong and Glover in 1857.

It is likely that at least part of the motive for the attempt was to allow Steve Spurling to add to his growing collection of images. This was a direct response to the rapid development of the tourist industry. In Tasmania at least, Spurling’s pictures and postcards would become as popular and prolific as those of Frank Hurley. The remote peak of Frenchmans Cap would make a very desirable addition to Stephen Spurling’s growing catalogue.

‘They have a long and arduous tramp before them,’ Charles Monds noted in his diary. ‘Our visitors have left us, loaded to the eyes and looking like pack-horses, were duly photographed in walking dress, and given a hearty farewell. Sad to lose them, they woke our camp up a bit and gave us a breeze of home.’

The next morning they managed with some difficulty to pick up the last vestiges of the old track. Since the early 1900s, the Linda Track had become very neglected. ‘About 5.00 p.m. we camped on the least wet situation available,’ recalled Steve Spurling.

Rain squalls continued the following morning. The Linda Track proved as difficult as ever to find in the wet scrub, and they made their own way through ‘the gloomy depths of a fair sample of West Coast bush’ to set up camp on the upper slopes of Mount Mullens.

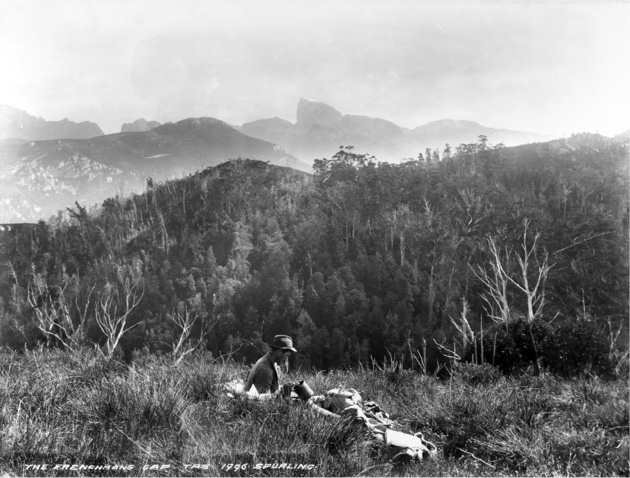

The next day, ‘We enjoyed from Mt Mullins [sic] our first view of the Frenchman’s Cap revealed in all its rugged grandeur, but still some miles distant.’ From here Spurling took an excellent photograph of the distant peak with Syd Yard in the foreground, one that has been reproduced many times over the years. They made their way down to the Loddon Plains in the afterglow of day, with the black silhouette of the Main Range standing out on the skyline, hopeful of a ‘field day with the cameras’ in the morning.

Syd Yard enjoys a meal on Mount Mullens, February 1920. (Spurling Collection, National Library of Australia)

With their food running low due to delays caused by dense scrub and bad weather, they looked hopefully to the Loddon Plains, but ‘the entire absence of game, with which we had hoped to augment our meat supply, showed we had miscalculated in that respect’. It was a serious oversight, and one that would cost them success in their attempt.

At the rocky summit of Pickaxe Ridge, their ‘furthest west’, they sat and ‘gazed at a spectacle of mountain grandeur which certainly is not surpassed, if equalled, in Tasmania’. Unfortunately smoke from a big bushfire drifted across to shroud their view, casting a yellow haze over the landscape and making further photography impossible.

They commenced the return journey and by the time they climbed over Mount Mullens, ‘darkness was upon our weary trio, and the descent over the rough button grass provided some unrehearsed tumbling feats. Startling crashes were heard when the cook came to earth with his billies and tinware, but the subsequent meal repaid us for our exertions.’ A weary tussle with scrub was taken up again next morning, the fallen telegraph line providing the only hint of the track in places. By now all that remained of their food supply were the few handfuls of rolled oats that each man carried in his pockets.

As night descended, the party resorted to ‘the old bushman’s trick of tying his handkerchief to his “dog’s tail” and following the man ahead’, the leader peering anxiously through the darkness for signs of the wire. It was 11.00 before they reached the Iron Store below Mount Arrowsmith.

Unlike travellers along the Crotty Track, ‘the Bushrangers’ had no first-hand knowledge of the country that lay before them. It was a pivotal and ambitious undertaking, the first by a modern bushwalking party. The journey had a far greater impact than any of them could have imagined. Their Lake St Clair camp appeared to have planted a seed of curiosity and adventure in the mind of Fred Smithies. In the coming years he would be driven by an ambition that eventually would make his name synonymous with Frenchmans Cap.