12 ‘The White Mountain Which Beckons from Afar’

We have made our stab at the Frenchman … and failed, just on the eve of success but are going to have another shot tomorrow. It is the biggest and hardest job of the kind that I have ever undertaken. My mate, R. B. Pitt, who is Assistant-Surveyor from this camp and who has naturally been through some rough country, and I stood appalled, when, after two days of hard battling through trackless and unknown country, we topped a long ridge up which we had climbed nearly 2,000 ft with heart-breaking packs, and looked down into the amazing defences of what I believe is our most wonderful mountain.98

So wrote Fred Smithies in February, 1928. At the time he was resting comfortably inside a tent in a survey camp beside the Franklin River, the guest of a party of workers constructing the new West Coast Road. Once Fred Smithies had a taste of Frenchmans Cap, scaling the peak became a compulsion for him. No matter how broken the terrain, how impenetrable the scrub, or cynical the words of others, his determination to reach the summit was unswayable.

In 1928 Frenchmans Cap was, in most people’s minds, the most remote and challenging peak in Tasmania. Ascents had been few and, apart from Charles Whitham’s attempt, little publicised. Locked away in the fastnesses of the west, many people believed Frenchmans Cap was beyond the reach of human endeavour.

Fred Smithies was born at Ulverstone on Tasmania’s north coast in 1885. Exploring and climbing mountains attracted him from an early age, and he quickly earned a reputation as a fearless mountaineer. Articulate and well-informed, his friendly face and pleasant disposition endeared him to many.

He was a man who quickly became enthusiastic, even passionate, about those things that interested him most. However, it was not until Fred was in his mid-thirties, with the advent of the motor car, that he undertook the epic bush journeys for which he is best remembered today: The Prince of Wales Range, The Eldons, Cradle Mountain and Frenchmans Cap.

Much of Smithies and Pitt’s route took them through dense scrub which they attacked with axe and billhook, a hafted tool with a sickle-shaped blade. They used the Pickaxe Ridge approach, then climbed the long ridge immediately to the east of Lake Vera. Up in the high country, the ridge they were following suddenly came to an end.

An immense, awe-inspiring gorge fully 2,000 ft deep, down into which there was only one possible track, and out of which only one possible track led up the lower slopes of the mount, and that was a very problematical possibility, for the bottom of the gorge and the first couple of thousand feet of ascent are covered with a tangle of the vilest scrub the West Coast can produce — and that, of course, is amongst the worst in the world.

The ‘track’ Smithies mentions would be one of their own making. Near the bottom of the gorge the scrub was so thick that pitching a tent was out of the question. Instead, they bivouacked under the stars ‘away down in the centre of an immense basin, completely surrounded by towering mountains ... at sunset, three black cockatoos, those evil precursors of bad weather, flew over our perch and screeched their warning at us ... the sun went down, our bowl filled from the bottom upwards with the darkening evening shadows, leaving us suspended at last in a great void of blackness with only the sky for a canopy ...’ They fell asleep in hopeful expectation of making the ascent the next day.

They awoke to a ‘falling glass’, and a blood red sunrise which, though beautiful, was an ominous forewarning of things to come. A gusty wind whipped wisps of fleecy scud across an otherwise clear sky. Smithies and Pitt continued preparations for the ascent. The wind soon increased to gale force, accompanied with startling rapidity by great masses of thickening black clouds. These soon rolled over Frenchmans Cap, enveloping the peak and darkening the whole sky. Heavy rain set in. With a limited supply of food, and the prospect of the Loddon and Franklin rivers flooding and cutting off their retreat, they were left with little choice but to return to camp.

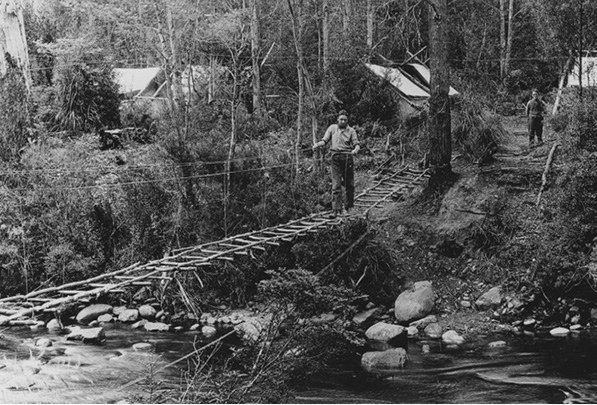

Ron Pitt crosses a shaky bridge over the Frankin near a Road Workers’ camp, February 1928. (Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office)

Two days later we were back in the survey camp where, by the way, everyone is most kind and where I have settled in as quite one of the family, sharing the chief’s tent in which, at the present moment, I am lying on my back writing with an inch of pencil. I want to get it off my chest while it is fresh. The weather was only playing with us, for after the first day it cleared and a beautifully fine spell set in.

So settled did the weather seem that Smithies and Pitt, now rested and re-provisioned, set off for another attempt. ‘Profiting from our previous experience,’ they made better time and by the end of the second day set up camp beyond their previous furthest point. They were up at daybreak with a light pack for the final ascent.

Ye Gods! What a day was that. Slashing, cutting and blazing, climbing all the time, we toiled up those slopes. For six hours fighting for every step, our clothes saturated with sweat, our tongues parched and swollen, for not once during all those hours, not indeed until evening did we find a drop of water. Eventually, exhausted and almost spent, we emerged from the frightful scrub into more open going and after a final stiff climb, reached the top of the range, with the great Cap itself apparently right against us, towering about another 1,000 ft above the spot we were on.

They gazed down at the sweeping valley before them. ‘The heights, the depths, the rugged stupendous peaks and cliffs of gleaming white quartzite were awe-inspiring in their wild immensity.’ Smithies believed there was a possibility of working their way around the ridge to the north, but there was no way of knowing what obstacles lay beyond. They had little time to consider their position, ‘for the mount had been gathering his forces together again and, as if to punish our presumption, loosed his fury on us in such a blizzard of wind and driving mists as in all my experience I have not endured.’

The wind was cyclonic in force and pandemonic in sound ... Did we attempt to speak, the words were whipped from our lips before they were uttered ... Though we did not reach the Cap itself, those few fleeting moments in the midst of all that scenery, its mystery and wonder accentuated perhaps by the fury of the approaching storm, amply repaid us for all the hardships we had gone through, and with the coming of the storm itself, came an experience which has left a rather lasting impression ... We failed in the ultimate object of our trip. Without water or shelter we could never have existed through the night on the wild mountain top, and could only once more retreat by the way we had come. But a trip, I think, can hardly be regarded as altogether a failure if for a single instant, it provides a thrill that goes to the depths of one’s very soul, as had this on more than one occasion.

‘An immense, awe-inspiring gorge fully 2000 feet deep’. Ronald Pitt (left) and Fred Smithies contemplate the descent, February 1928. (Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office)

The 1928 attempt left a deep impression on Fred Smithies. ‘So far, no other practicable means of approach have been discovered and gradually this, perhaps the most remarkable of all Tasmanian mountains, has come to be regarded as quite beyond the reach of those whose wanderings and inclinations lead them into the high ranges and lesser-known parts of our island state.’99 Far from discouraged, Smithies was determined to return to the peak at the earliest opportunity.

Smithies returns to Frenchmans Cap with Cliff Bradshaw in 1931

Fred Smithies was now convinced a western approach, from Queenstown, would provide an easier route to the mountain. Three years after his failed 1928 journey, Fred happened to strike up a casual conversation with Godfrey Bower, the sanguine proprietor of Harvey’s Hotel at Queenstown. In stark contrast to most others, Godfrey Bower actually seemed quite positive about Fred’s chances of reaching Frenchmans Cap. He even offered to find a local bushman to act as a guide. Fred explains, ‘I found that arrangements had been made with Mr Cliff Bradshaw, of Linda, to guide me through the difficult country.’

Cliff Bradshaw was born in 1905 in Maryborough, Victoria. He was raised in Queenstown, and as a young man worked underground on the North Lyell Mine, before moving to Crotty. After a brief stint working on the Kelly Basin Railway, Bradshaw turned his attention to working with timber. It was here, in the densely wooded folds of the West Coast Range, that he established a name for himself as a bushman and timber getter. At first he gained useful knowledge and experience working as a wood cutter, before turning to log hauling, working mainly with the valuable King William pine. Later, Bradshaw started a family milling business which endures to this day.

Smithies and Bradshaw spent a couple of days in Queenstown, getting supplies ready for the trip. Smithies discussed his proposed trip with a number of officials from the Mount Lyell Mine ‘who smiled feebly and said, “you won’t get there”.’100

‘On these doubts being conveyed to Cliff,’ Smithies wrote, ‘his invariable reply was: “I can get you there all right.”’ In the first week of March 1931, they started out along the Crotty Track, carrying enough food for seven days in packs that weighed over 50 lbs. Bradshaw’s faithful bush dog, Ginger, trotted along behind. At first the going was good, but they soon found out why the track had for so long been considered impassable.

Bauera meets overhead, preventing all visibility, and packs, feet and clothing entangle themselves in the wild riot of confusion on all sides ... The terrific exertion and expenditure of energy involved in negotiating such obstacles, with undergrowth tangling one’s feet and overgrowth catching one’s pack, have to be experienced to be believed. Every muscle in one’s body is brought into full play, and one marvels at the resilience and adaptability of the human frame to stand such a racking strain.

That night they camped near the banks of the Franklin, in the shadow of Mount Fincham. The next morning they discovered that all signs of the route had been completely obliterated by storms. Bradshaw resorted to burrowing deep down into the mossy entanglement to locate an old log end, cut by the axes of the original Crotty Track makers nearly 20 years before. It was a slow and tedious method of navigation, but it did confirm they were travelling in the right direction. After 10 hours of unremitting effort they had covered barely five miles.

‘A wild riot of confusion on all sides’. Cliff Bradshaw hacking through scrub near the Franklin River, March 1931. (Bernie Bradshaw)

Fully aware that the weather may hold for a day — and one day only — they decided to push ahead for the summit. They did so with just the food in their pockets. They bivouacked that night at the foot of the mountain, basking in the glowing warmth of a fire which they had patiently, over two hours, coaxed to life from wet Manuka boughs. ‘Our tea at 8.30 consisted of half a tin of sheep’s tongues between us with one small piece of bread.’

In the morning the track petered out in the scrub, and despite a careful two hour search they failed to pick it up again. To further compound their misery, a dense mist now descended over the whole of the Main Range, bringing with it the threat of heavy weather. Smithies and Bradshaw were left feeling disoriented and dispirited. Finally, at 11.00 — tired, hungry and with a sense of failure — they decided to abandon the attempt.

We were actually on the point of beating a retreat, when, as if staged for the purpose, the curtain of fog rolled up, and the glorious sunny day we had been hoping for burst upon us, and just across the valley the gleaming white mass of the Frenchman towered above our heads. Anything more dramatic it would be difficult to conceive as that wonderful view unrolled before us and the object of our desires revealed himself in all his beauty to our fascinated gaze.

A long, stiff climb still lay ahead, but with spirits revived they left North Col for the summit. ‘Here the climber is faced with a perpendicular wall of from 12 to 15 ft, and as the rather precarious and inadequate foot and hand holds lead diagonally across its face the depth of the drop beneath increases considerably, making altogether a very neat little nerve test.’ With this obstacle surmounted, it still took them the best part of an hour to reach the summit. By now they were feeling acutely the effects of lack of food.

... For my part it required a most prodigious effort to drag myself up that last 1,000 ft. With heart thudding from sheer exhaustion and weakness, and it was only resting every few minutes that one was able at last to stagger on to the pinnacle. Arrived there, however, the wonder of the scene was sufficient to banish all thought of weariness or hunger ... The panoramic view simply took one’s breath away.

On their return, Smithies wrote a lively account of their journey for the Weekly Courier. Entitled ‘The White Mountain Which Beckons From Afar’, the article reached a large readership and introduced many people to Frenchmans Cap for the first time. ‘Any hardship suffered was always subordinate to the thrill and excitement of overcoming the various obstacles,’ Fred explained to his readers. ‘One’s senses were continually delighted with the wild beauty of the country traversed.’

Fred contacted the only two people he knew who had climbed Frenchmans Cap. He wrote to Arch Meston, then headmaster at Devonport High School, and also to Charles Whitham. ‘I am glad to congratulate you on a very plucky and difficult enterprise,’ Charles replied. ‘It is 16 years since I was there, and even in 1915 [sic] two years after the track had been cut, there were many trees across it. I know what an abandoned West Coast track is like, and am amazed at your courage and endurance ... The trip, even when the track was in good order, from the Franklin to the summit was a very tiring one, the worst one-day task I ever encountered. The most exasperating part was the steep descent to Lake Gwendolen, and the climb from it — entailing a climb on the return journey ... I wish I had your physical strength, but I cannot take any more long trips, my heart won’t stand any strain.’101

For much of 1931, Fred toured the length and breadth of Tasmania giving lectures on Frenchmans Cap. Fred was a keen amateur photographer and he illustrated his lectures with a selection of lantern slides (which he carefully hand-coloured), a perfect accompaniment to his rich commentary.

His two journeys to Frenchmans Cap had been brutal, pioneering journeys undertaken at a time when the peak remained utterly remote. They would remain singular events in his life. Fred was convinced that the publicity his lantern lectures generated would ultimately force the government to consider reopening the Crotty Track. But neither Fred, Ronald Pitt nor Cliff Bradshaw could have guessed that the future way to Frenchmans Cap lay not from the west, but with J. E. Philp’s forgotten track.

The Lyell Highway

Not only did the Linda Track provide the only corridor to western Tasmania, it also carried the vital overland telegraph line. Frequent wild weather, however, often left the line fouled by fallen trees and heavy snowfalls.

To maintain this vital link, ‘linesmen’ were employed in 20 mile (32 km) stages between the Iron Store below Mount Arrowsmith and Strahan, to keep the line open and to repair breaks. It was important and often dangerous work, and one linesman even lost his life in a blizzard on Mount Arrowsmith. Others had to wade through deep snowdrifts and swollen streams.

The Iron Store below Mount Arrowsmith, February 1928. (Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office)

Hells Gates, the dangerous entrance to Macquarie Harbour, posed a hazardous obstacle to ships bound for Strahan. Eventually, sea freight began using the safer northern port of Burnie instead. The Emu Bay Railway, carrying both passengers and freight, now connected Burnie and Zeehan, and in 1902 a new telegraph line was strung beside the railway line. The Linda Track, as an access route and communications line, had outlived its usefulness.

The Linda Track and the telegraph line were left to fall into ruin. Several bridges were washed away and overgrowth rapidly reclaimed the track. From time to time it was cleared by survey parties, though mostly it remained overgrown and its state of neglect left it quite dangerous in places. In 1916, Charles Whitham wrote a pointed letter to the Minister of Lands voicing the concerns of many west coasters at the time.

I think it most discreditable to Tasmania that after more than 100 years of settlement there should be no convenient means of access to the West Coast except by sea, or by two days of circuitous road travel. A good road between here and Hobart would develop more tourist traffic from here to Tasmania felix than you people in other parts have any idea of.102

The benefits of a new road were obvious. Apart from forging a link with the rest of the state it would lure west coast people away from Victoria, where goods were traded, west coasters spent their holidays and even educated their children. It was also hoped that prospecting would be encouraged both north and south of the new road in the expectation of discovering new mineral fields.

After World War One, west coast residents and Hobart businessmen brought pressure to bear on the government of the day. A new road was agreed to in principle and though planning began in 1919, interminable delays meant that it would take another seven years for the five routes proposed to be fully surveyed.

As the highway project gained momentum, a number of bushwalking parties took to walking the Linda Track for the last time. One surprising visitor was Lord Stonehaven, Governor-General of Australia (1925–1931), who walked the Linda Track with his son and aide-de-camp over the summer of 1926–1927. Lord Stonehaven had visited Tasmania the year before, learnt of the Franklins’ journey of 1842, and was keen to follow in their footsteps, or at least replicate the first part of their journey.

They were guided along the Linda Track by the surveyor of the new road, Colin Pitt. A plaque at the King William Saddle acknowledges his work on the Lyell Highway, but Pitt’s influence went much further than just survey work. A man of integrity, common sense and reason, he remains an unsung hero of early conservation and environmental protection in Tasmania. His work as Chairman of the Scenery Preservation Board set him apart from his peers, and many of his decisions, where conservation prevailed over development, were almost visionary for his times. Succeeding generations owe much to Colin Pitt and his early initiatives.

In preparation for the Governor-General’s journey, the Linda Track had been roughly cleared, and wire bridges were strung across the Franklin and Collingwood Rivers. ‘His Excellency could either live on badger, kangaroo, damper, etc., or bring in things from civilisation as he required’, the vice-regal party was advised.103 The journey was a successful one and the event is commemorated today in Stonehaven Creek, near the start of the track to Frenchmans Cap.

In 1927, after much deliberation, a definite route through to the west was settled upon. Construction work on the new highway began a year later under the Federal Aid Road Scheme. In September 1929, the Premier, Mr J. C. McPhee, walked the route of the new road in wet and snowy conditions. By 1930, work was well under way, with 240 road workers busy constructing the Lyell Highway and living in tent camps pitched along the route of the new road.104

Most west coast people were certain the new road would be named Moore’s Highway in honour of local bush legend, T. B. Moore. This suggestion made sense as the new highway, with a few deviations, essentially followed Moore’s 1883 route. But the government finally decided upon the Lyell Highway after Mount Lyell overlooking Queenstown, whose mineral wealth had so revitalised the west coast and the Tasmanian economy.

The Lyell Highway took four years to complete and was officially opened at the King River bridge on 19 November 1932. Despite the controversy over the naming of the road, most people simply called the new highway the West Coast Road, a name which stuck for over two decades.

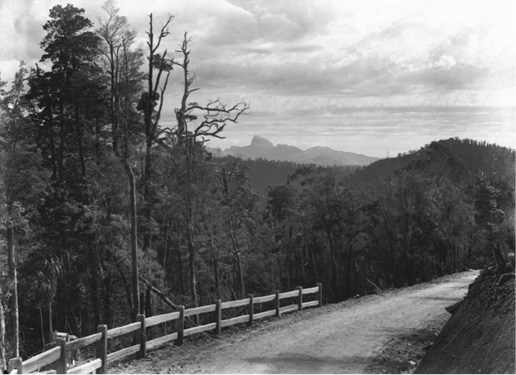

‘The West Coast Road’. A view of Frenchmans Cap from the newly-completed Lyell Highway. (Spurling collection, National Library of Australia)

For several decades, Road Patrolmen were employed by the Public Works Department (PWD) to maintain the gravel surface of the new highway. Referred to locally as ‘Seven Milers’, each patrolman was responsible for seven miles of road. These men maintained the road surface using only a pick, shovel and wheelbarrow. Patrolmen were busy men. The road had to be kept free of fallen trees and snow, drains had to be cleared, potholes filled and guide posts replaced.105

Patrolmen were also the motorist’s friend, giving advice on road and travelling conditions and assisting motorists in trouble. ‘One sometimes stopped for a yarn,’ recalled Chris Binks of the patrolmen, ‘in those unhurried times when cars were few and far between on the back roads.’106 Accommodation huts, small and spartan, were provided for patrolmen, many of whom had families.

The new road soon attracted its own residents and commercial interests. Dozens of huts and cottages dotted the length of the highway, their residents mainly involved in one form or another with the timber industry. Many individual wood cutters worked up and down the highway, all bent on meeting the seemingly endless demand for wood at the Mount Lyell Mine and firewood for Queenstown businesses and residents.

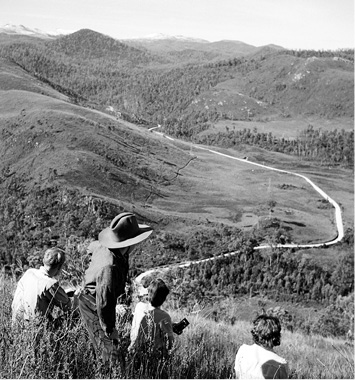

The Lyell Highway seen from Artists Hill,1948. The thin line of the old Linda Track can be clearly seen in the centre of this photograph. (Jack Thwaites)

A number of sawmills sprang up. Wright Brothers ran a sawmill at Victoria Pass and timber mills were also operated by C. A. Bradshaw and R. J. Howard at Princess River. Davies Brothers milled timber from the upper Franklin at Mount Arrowsmith.107 Even a pig farm was established at Nelson Valley. No overall planning was put in place for many of these little settlements, which often led to the serious pollution of nearby streams, later manifesting itself in health problems.

The little highway community presented the government with another problem. Within a few years of its opening, around fifty children were living along the road, all in need of education. The Education Department sent the Inspector of Schools to visit the area and to furnish a report. The Inspector recommended against the proposal of a new school. ‘The roadside population is a floating one,’ he reported, adding that ‘use should be made of the Correspondence School.’108

One of the early and enduring enterprises along the highway remains that of R. Stephens Honey. In early 1934, the company set up bee hives on Mount Arrowsmith for the production of leatherwood honey. Frenchmans Cap was used as a guide to the weather by the company’s workers: if the peak was clear of cloud, it was taken as a sign that a good working day lay ahead. Today, Frenchmans Cap still appears on the label of R. Stephens Golden Nectar Real Leatherwood Honey.

In 1935, Helmer Henry Hastings Huxley placed 43 bee hives halfway up Mount Arrowsmith overlooking Surprise Valley for the production of leatherwood honey.109 Affectionately known as ‘Taffy the Beeman’, Huxley alternated his hives between the flowering leatherwoods of Mount Arrowsmith and the Spring apple and pear blossoms of the Huon Valley for over 20 years.

Taffy made a living selling his honey at both locations, and invited people to sign his visitors books. A thousand people from all over the world left their names and comments in his books, including one American who made a point of visiting Tasmania after reading about Taffy in an article by photographer Frank Hurley.110 Taffy was also an experienced bushman who did work on the track to Frenchmans Cap for the Scenery Preservation Board and repaired wooden fencing along the Lyell Highway.

In early 1962, Tasmanians opened their morning newspapers to the news that Taffy, aged 78, had been murdered at his cottage on the Huon Road at Lower Longley. The crime was both heinous and inexplicable, and the theft of an insignificant amount of money, apparently the sole motivating factor, made it even more baffling. A man was later arrested, charged and found guilty of murder. Today, these events have faded from memory, though Taffy’s name is perpetuated in Taffys Creek, at the foot of Mount Arrowsmith.