13 Davern and Anderson Find Philp’s Track

… whilst scouting along the top of the ridge we were astonished to find stakes and blazes leading to Lake Tahune.

Fred Smithies’ newspaper article and lantern lectures drew an immediate response. Two young men, Geoffrey Chapman and Douglas Anderson, decided to attempt the Cap at the end of 1931. Chapman wrote to Smithies requesting route details, which he willingly supplied. Climbing Frenchmans Cap was just part of an ambitious journey Chapman and Anderson had planned from the Gordon Bend to Queenstown. The way led mostly through difficult and untracked terrain.

Geoffrey Chapman, 27, was a competent bushwalker and an excellent skier, who had spent the past 10 years making trips into the heart of the Southwest. ‘I will merely plead for three things,’ Chapman once declared, ‘adequate good food, broken-in, stout, well-nailed boots, and a waterproof pack.’111

Douglas Anderson. (Rosemary Coupe)

Douglas Anderson, 21, had also walked extensively in the Southwest. He was particularly fond of the peaks of the Western Arthur Range which, for him, seemed ‘to personify in their scarred and weather-beaten sides the very spirit of the south-west’.112 Chapman and Anderson came to know each other as foundation members of the newly formed Hobart Walking Club and the Ski Club of Tasmania.

It took them three days to traverse the King William Range and emerge on to the West Coast Road, which was then under construction. The next day, they crossed the Loddon River and camped at the base of Pickaxe Ridge at a spot Smithies had dubbed his ‘Honey Tin Camp’. It was on this trip that Chapman or Anderson (it is unclear exactly who) named Pickaxe Ridge. The ridge was named ‘The Pickaxe’, presumably after a prospector’s pickaxe was found somewhere along its length. They named the rocky summit of the ridge ‘Mount Pickaxe’.

In the morning the weather turned against them. Heavy rain was followed by hail which ‘soon became most torrid’ the higher they climbed. ‘Owing to the loss of a prismatic [compass] we did not get to the top till near 4.30 p.m.,’ Chapman informed Smithies. ‘I decided not to make any further attempt or proceed further on this way of approach. Descending the ridge again, Anderson by great luck recovered his compass ... it must be remembered that we, or rather I, looked on it [the ascent] from a cold-blooded way, knowing that the peak was accessible and several times scaled from the west. I did not think it worthwhile hewing for say, three days under the circumstances we were experiencing … getting up the ridge, being baffled by a fog, by a further gorge and completely crippling all of the party’s ankles.’113

The pair returned to the partly-formed West Coast Road and completed the final leg of their marathon journey to Queenstown. ‘The most strenuous part of the tour was traversing the entire length of the King William Range from south to north,’ Chapman wrote, ‘over and along the ridgetop all the way, carrying at least 50 lb packs.’ Anderson and Chapman continued to walk in the Southwest and probed for early routes to Federation Peak. Mount Chapman and Anderson Bluff stand as memorials to their early work in that region.

Within a few years of Chapman and Anderson’s 1931 trip, the name Pickaxe Ridge came into common use by fellow members of the Hobart Walking Club. In 1953, the name was formerly accepted by the Nomenclature Board of Tasmania. Over the next four years, both men returned to the region on separate trips that would help define the modern story of Frenchmans Cap. Douglas Anderson returned first, 12 months later, with Aubrey Davern. It was a journey that would change not only the way Frenchmans Cap was approached, but also within a few years would even change people’s perception of the mountain.

The discovery of Daverns Cavern

It was late December, 1932. High up in the Main Range two figures scrambled below its soaring crags and spires. The weather was terrible. It had been raining all day and both men were cold, wet and weary. In failing light, they battled for hand and footholds in the prickly scrub hugging the exposed ridge up which they were working.

Their situation became serious. The full force of the storm was upon them and they braced themselves against icy blasts of sleet and rain. After much scrambling and slipping, they worked their way up the steep slope to find themselves standing at the foot of a huge, impassable column of rock. One of them climbed a tree growing out against the rock face, gained a precarious foothold on a small ledge, and pulled himself up. He was amazed to find himself peering into the mouth of a large cave.

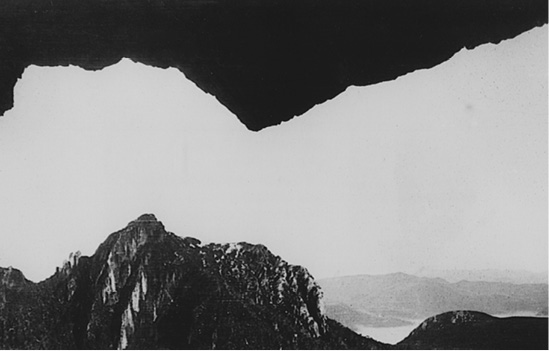

From Daverns Cavern. Douglas Anderson’s original photograph looking towards Pine Knob, December 1932. (Nancy Anderson)

The discovery of Daverns Cavern is one of Frenchmans Cap’s enduring stories. Davern and Anderson stumbled upon the cave in the early part of a journey undertaken to disprove the long-held belief that it was impossible to reach Frenchmans Cap from the east. Smithies had been the most recent to perpetuate this view, after his failed attempt with Ronald Pitt in 1928. Most, but not all, previous parties had failed because they had been unsuccessful in locating a high level connecting route to the peak. Some earlier parties had made the serious mistake of leaving the ridges and descending to the densely forested valleys which hug the lower slopes of Frenchmans Cap.

Aubrey Davern was aged 31, and worked for the Education Department. He knew Douglas Anderson through the Hobart Walking Club and the University of Tasmania. They were the first Frenchmans Cap party to enjoy the luxury of travel along the new West Coast Road to deliver them to the start of their journey. All previous parties from this direction had been obliged to start from the King William Plains, then follow the Linda Track over Mount Arrowsmith.

Davern and Anderson began their journey on Christmas Day, 1932. They left the road near Stonehaven Creek ‘in the teeth of a snowstorm’, as Aubrey Davern recorded in his diary. Miserable weather continued for the next two days, and when they left their campsite at Vera Creek on the morning of the third day, conditions still remained rainy, bleak and cheerless. Climbing high above Lake Vera, the long scrubby ridge up which they scrambled presented them with button grass, bauera, tea tree and cutting grass, obstacles which Davern described as ranging ‘from good to very bad’. As they worked higher up into the crags and ridges of the Main Range, they were greeted by an unwelcome icy blast. Conditions were getting steadily worse.

We reached the point where Smithies had been confronted by the impassable chasm and it looked for a while as if Smithies had been right, for it was a daunting sight on such a day — and that terrific cleft gaping 2,000 ft right in our path. We were very relieved to find, however, that what appeared to be an abrupt end to the long ridge we had been climbing had a kind of dog’s leg bend in it, and that by veering to the left we could cross a col connecting with the next section of the ridge.114

By locating this elusive connecting ridge, Davern and Anderson had discovered a practicable, high level approach to Frenchmans Cap. It was an approach that for a hundred years had frustrated and thwarted many attempts. It had eluded Sharland, probably both Sprent and Strzelecki, Smithies and numerous prospecting parties. As they scrambled up the scrubby slope to the foot of ‘a huge column of rock, quite unscalable’, the weather finally broke, stormy and bitterly cold, just as Douglas Anderson swung himself up onto a rock ledge.

He found himself on a well-wooded natural platform, which was, as it were, the front garden of a very commodious cave, with practically all mod cons — water laid on by a natural drip which filled the billy in less than a minute, fuel all about the ‘front garden’, large ledges which could be used for kitchen table and built-in shelving, ample light from the very spacious opening, plenty of room for dry sleeping (a party of five of us slept there a year later and weathered out a three-day blizzard in bush comfort), complete privacy from neighbours, an impregnable tenancy for as long as we liked, and a view of unimaginable beauty that could be ‘built out’ only by a geological cataclysm of titanic magnitude.115

That night the wind rose to a howling gale. ‘Nothing could have been more welcome than the “Hollow Tooth”,’ wrote Aubrey Davern from within the cosy confines of the yawning cavern, perched on an exposed ridge at a height of 900 m.116 That night they slept comfortably as heavy snow alternated with hail storms. For the next 48 hours, they sat snug in their lofty mountain cave, watching the grand spectacle of snow driving down the valley before them and congratulating themselves on their good fortune in finding so timely a refuge.

Mouth of Daverns Cavern. (Simon Kleinig)

We did not stir beyond the cave except to gather in more fuel, and witnessed the most spectacular and prolonged snow storm I have ever experienced (Canadian winters included), and when we emerged late on the fourth day to take stock of our position the whole Frenchman range was thickly covered in snow. Anderson and I called the cave the ‘Hollow Tooth,’ partly from the fang-like appearance of the great rock sticking up on the gum of the ridge, partly because the cave resembled a hole in the molar.117

The fifth day dawned clear, mild and sunny, and when they emerged from the mouth of the cave they found the snow already beginning to melt. Conditions appeared perfect for an attempt at the peak, so leaving their gear at the ‘Hollow Tooth’, they picked out a route along the Main Range with Frenchmans Cap now before them, a little over three kilometres away.

View from Daverns Cavern to Pine Knob. (Simon Kleinig)

We found our way on to the main ridge with some difficulty in one or two pinches, and whilst scouting along the top of the ridge we were astonished to find stakes and blazes leading to Lake Tahune. The markings were indistinct in places, but some of the stakes and many of the blazes remain clearly marked. This was Philp’s track, cut twenty-two years before, all records of which had been lost. In all, we followed this track for nearly a mile and a half. It brought us by a good route round a high, rugged peak that rears itself up opposite the towering cliffs of the Cap, and so on to the outlet of a beautiful lake (named by Mr Philp, Lake Tahune), almost buried by high rock walls, and lying right under the Cap’s precipitous face. The wild and magnificent setting of this lake baffles description. It must be seen to be realised. By the creek running from the lake we found a prospector’s shovel.118

They climbed up to the ‘knife-edged saddle’ of North Col on a cloudless summer’s day, the recently fallen snow around them glittering with a dazzling whiteness. On Frenchmans Cap, snow was melting rapidly in the summer sun, spilling from rock ledges in cascades, tumbling over the eastern precipice and falling in great veil-like mists to the lake far below.

At North Col, Davern and Anderson roped up. ‘From here the final climb faced us. The Frenchman’s last line of defence is an awkward cleft in the rock wall, up which we had to scale to get on to the great rock mass. It was the most difficult pinch in the whole journey, but, once compassed, the remainder of the climb was reasonably good. After nearly two hours on the top in weather that was warm and windless, we descended to a neighbouring ridge for lunch, from where we made the return journey to the Hollow Tooth in two hours.’ They returned to the West Coast Road the way they had come, the benefit of much lighter packs enabling them to make the return journey in half the time.

Two days later a small column appeared in the Mercury: ‘Frenchman’s Cap — new route discovered’.119 Eleven days later another article, ‘Conquest of Frenchman’s Cap’, appeared in the Illustrated Tasmanian Mail, written by Aubrey Davern and giving a detailed account of the journey, with accompanying photographs. The ‘Hollow Tooth’ was used by many parties over the next few years and the first hand-drawn maps of the region gave clear instructions on how to locate it. Some maps even contained illustrations of the cave.

The cave soon came to be known as ‘Daverns Cavern,’ a name officially accepted by the Nomenclature Board of Tasmania in 1953. Replying to a letter from Benjamin Whitham (brother of Charles Whitham) in 1953, Aubrey Davern wrote, ‘I had forewarning about the appearance of “Daverns Cavern” on the map in the form of a notice in “The Tasmanian Tramp.” “Daverns Cavern” might with more justice have been named “Andersons Antrum” without any loss of euphony, for it was Douglas Anderson who made the actual discovery in December, 1932.’

Davern and Anderson’s journey was highly successful on a number of levels. First, it shattered the myth of the inaccessibility of Frenchmans Cap from the east. It also marked the first recorded ascent of Frenchmans Cap from this direction for 75 years — since Tully, Spong and Glover’s in 1857. Davern and Anderson’s location of an access route was an excellent piece of navigation under difficult conditions, together with the unexpected discovery of Daverns Cavern.

Most important, though, was their discovery of Philp’s 1910 track, which initially they mistook for the work of prospectors. With a cleared access corridor through very rough country, no longer would Frenchmans Cap remain locked away, to be visited by the occasional prospector only.

Davern and Anderson’s discovery of Philp’s Track coincided within weeks with the opening of the Lyell Highway. These two events suddenly made Frenchmans Cap accessible, and the long years when the mountain was considered impregnable were drawing to an end. A new era in the story of Frenchmans Cap was about to begin.