14 A New Era

The Frenchman rears his glistening top ahead, and the way is along a ridge ending at Lake Tahune.

Aubrey Davern had not finished with Frenchmans Cap. He was curiously intrigued by their chance discovery of Philp’s track. Shortly after his return, Davern arranged to meet J. E. Philp at the latter’s home set on the heights overlooking picturesque Lindisfarne Bay. ‘It was purely by accident that Davern heard that I had cut a track,’ J. E. Philp replied to Fred Smithies, ‘as he thought he had pioneered a way from the eastward. He did in a way but hit on my track by accident, and thought it was a prospecting job.’120

Encouraged by his meeting with J. E. Philp, Aubrey Davern planned another journey 10 months later, in December 1933. Davern had no trouble forming a party. Several fellow members of the Hobart Walking Club — Desmond Giblin, Jock Turner and Balfour Johnston — all stepped forward. The party was completed by 17 year-old David Philp, youngest son of J. E. Philp, who probably went along at the suggestion of his father.

Davern’s party passed Philp’s 1910 sign, fixed to a tree, indicating the way across the button grass expanse of Philps Lead. A few of Philp’s burnt stakes even marched away into the distance, until the button grass melted into dense forest. Late in the afternoon they set up camp at the western end of Lake Vera. Des Giblin explains:

Watching the day break from our tent next morning we saw the beauties of Lake Vera from a new angle, for as she lay half in darkness in the shadow of the hill, the sun lit up the western shore, and drew from the chill waters a filmy veil of mist. The old man’s camp, too, was just as he had left it; the logs, floorpoles and uprights differing only in shape from the moss covered limbs and boles of the sassafras and pines about them; untouched since Philp had left them twenty-three years before.121

Davern successfully managed to locate the ‘Hollow Tooth’ once more. Seen in profile from the west, the Hollow Tooth sits squarely along a narrow ridge which it shares with another rocky feature named, descriptively, ‘The Ram’. A short, narrow ridge separates the two features.

This was to be our camp for three bitter days of blizzard. Wood was scarce and very wet, and ironically enough, water, which was everywhere around us, could only be obtained by catching it in plates as it dripped from the roof. There was some comfort, however, in contemplating from our sleeping bags the storm as it drove furiously past, blotting out the depths of the valley below.

They climbed the Cap the next day, and the morning after that left for the West Coast Road, the first known party to pioneer a return route over the Raglan Range. It turned into a difficult and trying undertaking. One patch of bad horizontal scrub required ‘nearly an hour to do 200 yards’. Bivouacking overnight on the slopes, they located a scrub-choked gully in the morning, down which they descended to the gorge.

Aubrey Davern’s party on Frenchmans Cap, December 1933. Left – Aubrey Davern, Balfour Johnston, David Philp, Desmond Giblin. (David W. Wilson)

Here, Davern ‘set the example’ by rolling over the top, pack and all, and down the slope. Then, by sliding the final 10 m down the smooth trunk of a tree, he stood finally at the water’s edge, near the Irenabyss. Young Philp offered to swim the Franklin River with a rope, the gear was taken across without incident and an hour later the party stood on the other side, ‘wet and shivering, but with all our gear dry’. A sudden change in the weather meant it took another two days for the party to cross the Raglan Range and descend to the West Coast Road.

Davern’s party had planned their journey with sufficient food to last 10 days. With weather delays, it had taken 13 days to complete, and for the last three they survived on a ‘hard’ ration of lima beans — literally. ‘The lima beans never softened,’ Des Giblin explained 45 years later, ‘even after soaking in water for two days, bashing thereafter with the back of an axe and treating the gravelly product in the pan with dripping.’

Aubrey Davern’s second journey, like the first, had produced worthwhile results. Philp’s track, overgrown in some parts yet surprisingly clear in others, had for the first time been followed for its entire length. An exit route over the Raglan Range had been pioneered, and the sister peak to Frenchmans Cap — Clytemnestra — had been named, together with White Needle and Pine Knob. Davern’s 1933 trip would, however, be the last journey of a true pioneering nature to Frenchmans Cap. Future bushwalking parties would find that the exploratory ground work was now complete.

Aubrey Davern later reflected on his two pioneering trips:

The Frenchman had become legendary for the difficulties it presented to climbers, especially after Fred Smithies lectured far and wide on his experience. The trip Anderson and I did was a tough one. The second trip when we picked up the whole of Philp’s track, except for a mile or so where we made an error of judgment, made it clear that henceforth the Frenchman could be climbed by practically anybody who had the use of his or her legs.122

The opening up of the Frenchmans Cap region

The discovery of Philp’s Track in 1932 made access to Frenchmans Cap a practical reality. Soon a regular return bus service was introduced between Hobart and Queenstown. It was now possible to take Guy’s service car, a small bus seating about nine people, and travel in comfort through to the west the same day.

Despite recent publicity, the influx of visitors during the 1930s took more the form of a trickle than a rush. Track or no track, Frenchmans Cap’s grim reputation as a wilderness mountain locked away somewhere in the remote west was still fixed firmly in people’s minds.

Many early bushwalkers carried maps that indicated the way to Frenchmans Cap lay along ‘Moore’s Track’, three kilometres east of the present track to Frenchmans Cap. A sign had even been erected: ‘To Calder’s Pass and Moore’s Track’. Moore’s Track was cut in 1900 by J. L. A. (James) Moore, younger brother of T. B. Moore. However, by the 1930s, most of Moore’s track had been reclaimed by scrub. Bushwalking parties soon found themselves in trouble, though some did manage to locate some of James Moore’s old stakes on the eastern slopes of Mount Mullens.

The opening of the new West Coast Road attracted more than just bushwalkers to the Frenchmans Cap region. The Abels — father Barnes and sons Ron, Basil and Charles — had previously hauled their heavy punts up the Franklin and Jane rivers to access stands of pine. This proved very hard and time-consuming work.

However, by using the new West Coast Road, the Abels would be able to provision their camps by ‘packing’ in their supplies from the road. This was arduous work, too, but preferable to the heart-breaking labour of man-hauling supplies up river.

Charles Fidler, a Forestry Officer and seasoned bushman, was probably responsible for marking out the route that the Abels would later cut as their track to the Jane River. Fidler was a frequent visitor to the Loddon Plains in the late 1920s and 1930s. He possessed an intimate knowledge of the Frenchmans Cap country that the Abels would have lacked. Fidler’s position in Forestry also allowed him to liaise and get approval from Colin Pitt, chief surveyor of the new highway.

In 1934, the Abels devoted 16 weeks to cutting their packing track. In essence it forms the present track across the Loddon Plains. The Abels’ Track passed through more open, if wetter, country than Moore’s Track, which lay as much as five kilometres to the east. A new hut was built by the Abels at Jane River, to serve as a base depot for incoming supplies. The distance from the West Coast Road to the Jane was a taxing 37 km. Charles (Chut) Abel recalled the journey in later years.

When I used to pack out to the Jane — in summer it’s not too bad, but try it in the winter time when you’ve got snow up to your knees and the rivers are in flood, the Sodden Loddon, they called it, the Loddon Plain. Basil and I one winter were going in there and Basil tripped and his pack landed on the back of his neck and pushed his face into the mud. If I hadn’t been there he’d have suffocated, he couldn’t get out ... You could only get food in by packing it, no other way, the ground was too soft for horses. Those button grass plains would bog a lizard!123

The Abels made many trips down the Loddons, expending an amount of labour quite unimaginable today. At the end of nine months, a comfortable base camp had been established in their Jane River log cabin. In 1935, Balfour Johnston, a Hobart Walking Club member, visited the hut and described both the contents and the astonishing logistics of provisioning it.

The hut was crammed with provisions and equipment, bags of flour, onions, sides of bacon, and tinned goods of every description. There were three iron camp ovens, one dozen axes, huge blocks and hundreds of feet of rope. All this had been carried in on their backs over 21 miles [sic] of difficult mountainous country from the West Coast Road. Later we learnt that they had been packing for nine consecutive months.124

For a few years from 1934, the Abels took to prospecting in the Jane River area. They were there when the big ‘rush’ began in 1935 and quickly took out leases. But their success, like most others, was limited and fleeting. Around 1937, they gave up gold fossicking altogether, let their leases lapse and returned to what they knew best — pining. This was more than 30 years after the region was abandoned by piners mourning the tragic drowning of John Stannard in 1901.

Eventually, most of the accessible pine was cut out of the Jane. What remained was locked in the river’s three formidable rocky gorges, where felled logs frequently jammed, or were too hard to get out to market. The last of the piners working near Frenchmans Cap were Ron, Keith and Reg Morrison.

In late 1939, in a seemingly impossible 16 day journey, the Morrison brothers, Ron and Reg, took their punt upstream from Deception Gorge (The Great Ravine) through the wild gorges and dangerous waters of the Franklin to Mount Fincham. From here they cut upstream as far as the Loddon River, which also contained good stands of pine, but within a few years most procurable pine had been cut from the region.

Boss-Walker and Norris

The first parties to use the track to Frenchmans Cap were members of the Hobart Walking Club. This is hardly surprising, as each returning party passed on valuable information to the next. Ian Boss-Walker and R. Allison Norris undertook a 10-day trip in February 1934, six weeks after the return of Aubrey Davern’s party.

Ian Boss-Walker was a keen member of the Hobart Walking Club, though today nothing is known of the identity of his companion, Allison Norris. In 1952, Ian Boss-Walker published Peaks and High Places, an informed and popular guidebook to the Cradle Mountain–Lake St Clair National Park. This first guidebook to the region served as the standard reference work for over 20 years and was reprinted several times in two editions. The pair began the trip equipped with route notes provided by Aubrey Davern which Ian Boss-Walker later described as ‘very accurate’.125

Much time was lost trying to locate traces of Moore’s old track. The open button grass plains were better, but the forest sections and the track around Lake Vera, littered with fallen timber, invariably made for slow going. Even worse was the smoke from purpose-lit bushfires, usually the work of prospectors. These dangerous wildfires were a frequent blight on the Frenchmans Cap landscape of the 1930s.

‘We reached the [Barron] Pass three hours and ten minutes after leaving Philp’s camp,’ wrote Ian Boss-Walker. ‘Got a magnificent view of the Frenchman. The Pass was burnt out, and also the crags on the Lake Vera side.’ On their way back they discovered to their dismay that the Loddon Plains had also been burnt, and after winding through the blackened Franklin Hills and over the fire-scorched slopes of Mount Mullens, they stood beside the Franklin River, where the ‘fires had burnt to the river’s edge’.

Emmett, Thwaites and Giblin

E. T. Emmett, Jack Thwaites and Des Giblin made their trip to Frenchmans Cap in March 1934, only weeks after Boss-Walker and Norris. E. T. Emmett was the first director of the Tasmanian Government Tourist Bureau, and a great lover of Tasmanian landscapes. He was raised in the bush within sight of ‘The Nut’ at Stanley, and felt a strong affinity with Tasmania’s wild regions all his life. Both a knowledgeable and enlightened man, E. T. Emmett had a clear vision for the future direction of Tasmania’s burgeoning tourist industry.

Jack Thwaites was a young public servant in the process of discovering Tasmania’s wildest and most spectacular regions. His family emigrated from Kendal in England’s Lake District in 1913 when Jack was 11, and from an early age he discovered a love of the natural world that would last all his life.

E. T. Emmett and Jack Thwaites founded the Hobart Walking Club in 1929. A valuable addition to the party was Des Giblin, who had returned from Frenchmans Cap only three months earlier with Aubrey Davern’s 1933 party.

The autumn weather was fine and sunny. Late on their first day they caught a dramatic glimpse of Frenchmans Cap from the slopes of Mt Mullens: ‘Tonight he is catching the last rays of sunset, and is a glowing pillar of fire,’ Jack Thwaites recorded in his diary.126 The next day, above Philps Lead, they spent five exhausting hours forcing their way through a tenacious tangle of forest and scrub. ‘Tea-tree, cutting grass and bauera grasped our packs, encircled our legs and lacerated our hands,’ Emmett explained. ‘All through it, sweat, swear-words and swag-ache were our companions.’ Finally, they made their way down in the soft light of late afternoon to ‘a sheet of water known to the dozen or so people who had seen it as Lake Vera.’127

The next day began with a steep climb up to Barron Pass. At last light, at the end of a long day and fatigue notwithstanding, E. T. Emmett described their journey through scenery which never failed to inspire:

It took from daylight till dark to travel the three or four miles separating Lakes Vera and Tahune. The scenery is both delicately beautiful and inspiringly grand. Through the forest in the ascent of the outliers of the ‘Frenchman’ are scores of trees, the boles of which are festooned with climbing heath, scarlet and tangerine fungi brightening fallen tree trunks, and a grove of giant grasstrees was passed, one specimen reaching probably 50 ft in height. Great white cliffs wall the ascent, and at the summit of the divide the Barron Pass provides an awe-inspiring spectacle. The Frenchman rears his glistening top ahead, and the way is along a ridge ending at Lake Tahune.128

‘We have pitched our tent on the lip of the valley above the lake, and have a stupendous view out to the east,’ wrote Jack Thwaites. ‘We turn in at 9.30 p.m., on a bed of pandanni leaves, and use the growth of centuries to rest our weary bones.’ E. T. Emmett was equally enthusiastic: ‘I cannot describe Lake Tahune adequately. The immediate surroundings of this sepia pool are pines, and right out of it for a sheer couple of thousand feet rise the white cliffs of Frenchman’s Cap.’ The next day dawned fine as they set out for the summit. Jack Thwaites described the ascent.

The rope came in useful to negotiate one of the chimneys leading up through the lower tier of a wall of the mighty Frenchman, then a few twists and turns up the ledges, and a quick walk up the stony plateau, and the cairn at last — 4,756 ft [sic]. We found another lake down the plateau to the west, quite a large lake, which does not appear to have been named. I took the liberty of naming it Sophie, after the wife of E. T. Emmett, Director of the Government Tourist Bureau, and leader of this party.129

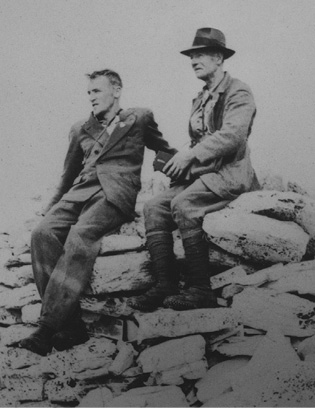

Jack Thwaites and E. T. Emmett on Frenchmans Cap, March 1934. (Jack Thwaites)

E. T. Emmett later wrote of the difficulties of route-finding on this 1934 trip. He claimed that three quarters of Philp’s stakes had perished and that tea-tree, bauera and cutting grass had obliterated sections where the track passed through scrub. Old slashes and tree blazes were difficult to locate. ‘In our dreams we still sought stakes and blazes and axe cuts,’ E. T. Emmett wrote in an early edition of The Tasmanian Tramp.130

Despite the hardships, Frenchmans Cap left an indelible impression on E. T. Emmett: ‘These mountains of the west have to be seen to be believed.’131 At the age of 64, E. T. Emmett surely must have considered climbing Frenchmans Cap an impossibility only a few years earlier. Jack Thwaites believed Emmett prized this accomplishment above all others. ‘It was worth the effort just to see the obvious delight on Em’s face as he sat happily on the summit cairn, enthralled by the vast sweep of surrounding country and rugged mountains.’

This was to be the first of many journeys to Frenchmans Cap for Jack Thwaites. Others had pioneered the opening up of the mountain but it would be Jack Thwaites, more than any other single person who, over the next forty years, would nurture the conservation of the Frenchmans Cap region through to the modern era. Jack Thwaites climbed Frenchmans Cap for the last time at the age of 75, only two months after standing on the summit of Federation Peak.

Jock Turner was another Hobart Walking Club stalwart who made repeated journeys to Frenchmans Cap in the early days. Born in 1898, of lean and wiry build, Jock was a man of few words, but a determined and indefatigable walker and a tower of strength on any trip, quite unflappable in the face of difficulties. Jock had been a member of Aubrey Davern’s 1933 party, and returned to the peak with Max Wilson for five days over the Spring of 1934. ‘We decided to go straight to the cave [Daverns Cavern] instead of going straight to Lake Tahune,’ Max Wilson recorded in his dairy.

As they clattered across the scree slope below the soaring spire of Nicoles Needle, they could see snow falling heavily over Frenchmans Cap and Lake Tahune. The cave offered a much drier and warmer alternative. The next day, they ‘followed the old blaze marks to Lake Tahune, having to plunge our way through about two feet of soft snow’. They climbed the Cap in indifferent weather, ‘the rope being of great assistance’ on a cold October day when the shores of Lake Tahune lay a metre deep in snow.132