15 More Trips along the Track to

Frenchmans Cap

I made eight trips to the Frenchman, got to the summit five times, saw the view twice.

Towards the end of 1935, the Abels’ packing track was upgraded by the Public Works Department (PWD). This work was carried out in direct response to the discovery of gold at Jane River. The upgraded track soon became known as the Jane River Track (later the Old Jane River Track, to avoid confusion with the New Jane River Track, built four years later).

The new PWD Track began on the West Coast Road below Artists Hill, a few hundred metres east of Stonehaven Creek. The start of the PWD Track ‘split’ the other two tracks that led in from the West Coast Road at that time. The Abels’ Track began 2.5 km to the west, while the track cut by James Moore lay about the same distance to the east. The present track to Frenchmans Cap follows the approximate route of the 1935 PWD Track across the Loddon Plains.

The new PWD work included the construction of a substantial log bridge over the Franklin River. Completed in December 1935, the bridge was wide and sturdy and was supported by log pile foundations driven deep into the river bed. The bridge was built wide enough to accommodate teams of horses hauling logs. The track itself was well built to receive both foot and horse traffic and was carefully benched around hillsides. Muddy sections were minimised by laying the track with cordwood (pieces of wood cut to uniform length and laid parallel to provide an even walking surface).

The Forestry Department was keen to make the track suitable for horses. But Forester Charles Fidler made it abundantly clear that this was a practical impossibility.

In the first instance, it would not be possible to lead even a blindfolded horse over a swaying bridge; secondly, the nature of some of the country over which the track would have to pass would not stand horse traffic, being very wet and boggy button grass plains; thirdly, the track would have to negotiate some very steep mountainous country, which would be practically impossible for a horse to walk over with a load; and fourthly, the fodder problem for a horse would be very difficult, for everything would have to be carried.133

Horses were used on the well-constructed, early sections of the track, but no horse ever got beyond the Loddon River. Logging the big trees south of the Franklin River was a lucrative activity. So vital was the bridge to this enterprise that one local merchant and timber getter, M. J. Penney, offered to pay for the new bridge and even to construct his own, just so he could access big trees on the other side; the stumps of these trees, mainly eucalypts, can still be seen today.

The PWD log bridge across the Franklin withstood raging floodwaters and heavy horse and foot traffic for the next 13 years. It was near the site of the old log bridge that the Frenchmans Cap flying fox was erected in 1949. Later still, the present suspension footbridge over the Franklin River was constructed. Well-made, benched sections of the Old Jane River Track can still be seen on the approach to Mount Mullens.

At this time the Old Jane River track crossed the Loddon River and its tributaries in at least three places, all bridged with fallen logs. The 1935 PWD log crossing of the Loddon River was flattened using adzes to provide an easier walking surface for top-heavy packers. Other log crossings provided the luxury of rough handrails. Today, for the more adventurous, remnants of these old bridges can still be found along the forested and fern-fringed banks of the Loddon River.

To provide emergency shelter for travellers, several huts were built between the West Coast Road and the Jane River goldfield; all have long since disappeared. By 1935, Stonehaven Hut had been completed. Constructed from wood and iron, Stonehaven Hut stood near the start of the track on the West Coast Road, and was probably erected by the PWD for storing materials used during construction of the Old Jane River Track. An attractive log cabin, built as an emergency shelter by the Abels, stood about two kilometres south of the turnoff to Philps Lead. This was a welcome refuge for the first bushwalkers to Frenchmans Cap, until claimed by fire in 1940.

Another hut stood at Detention Corner, at the southern end of the Loddon Plains, below Counsel Pass. This hut was known, appropriately, as Half Way Humpy, or Half Way Dump, and was built by the PWD. It was still being used by parties well into the 1950s. In the absence of a hut logbook, thylacine searcher David Fleay had written his name on the back of the hut door.134 Another split pine hut with a shingle roof was located at the Jane River goldfield. The earlier log cabin built by the Abels for their supplies stood beside the Jane River, some distance south of the diggings.

Halfway Humpy. Chris Binks stands outside an old packer’s hut near Counsel Pass on the way to the Jane River, January 1951. (David Pinkard)

Prospector’s sustenance allowance

Times were tough in Tasmania in the early decades of the 20th Century. More misery followed the carnage of World War One when the American Stock Market collapsed in October 1929, triggering a worldwide economic recession. From 1929 until at least the mid-1930s, Tasmanians languished under the effects of the Great Depression. During this time, the state government made available a ‘prospector’s sustenance allowance’, provided under the Aid to Mining Act 1927. The allowance was designed to encourage prospecting throughout the state, particularly in the minerals-rich west. The expectation, of course, was that a major mineral discovery, or a succession of them, would provide a much needed stimulus to Tasmania’s beleaguered economy.

There were over 2,000 applicants; of these, 1,200 were allocated a sustenance allowance. The allowance was intended to subsidise the cost of food and equipment necessary to keep a small party of men in the field. To be successful, applicants had to satisfy the government that they had some knowledge of prospecting and had been into known mineralised areas.

One of the first to receive the sustenance allowance was a hardy prospector by the name of Sydney Laughton. A veteran of the Boer War, Laughton had served as a Lance Corporal with the 1st Tasmanian Imperial Bushmen. By the 1920s, Laughton was middle aged and widely experienced in bush work. As well as prospecting, he had helped cut Robert Thirkell’s Track of 1908.

Laughton was granted sustenance allowances for two trips in 1929. Why he would bother to struggle into Frenchmans Cap in the depths of a harsh winter remains a mystery. Perhaps the trips were driven simply by need. By now the Great Depression was beginning to bite down hard on many Tasmanians.

Laughton and his companion struggled across the Loddon Plains and into ‘the heaviest snowstorm I have seen in Tasmania’. Despite being in ‘extreme difficulties’, they reached Calder Pass, then waited for a couple of days, hoping that the storm would pass so they could begin their search for minerals near the Jane River.

If anything, the snowstorm only increased, so ‘we packed up and struggled through three feet of snow and slurry back to the Frenchman plain, carrying 56 lbs each and arrived at our previous camp thoroughly knocked up’. They attempted further work on an iron lode in the Franklin Hills, ‘but found ourselves baffled still, the whole place being completely smothered up’.

There was now little choice but to return to Derwent Bridge. It took them over two days to reach the shoulder of Mount Arrowsmith, struggling through ‘immense drifts on either side, blundering on, falling down buried to the waist’. Snow continued falling heavily and the cold became intense, biting and penetrating. Their situation was becoming more desperate by the minute.

Laughton drew on all his bushman’s ingenuity to get them through. There was no choice but to bivouac immediately in the only shelter they could find — a scrubby patch of tea tree. They foraged around for as much wood as their frozen hands could gather, most of it green and saturated.

Standing there, we felt we must freeze as we stood unless we could get a fire which seemed impossible with three feet of snow … digging up dry paper we soon burnt it out and felt that we were beaten and done for. Luckily the writer, fumbling for something that would burn, struck about two inches of candle and in a few minutes managed to get a blaze—that piece of candle undoubtedly saved our lives. It was as good as a flask of brandy.

Laughton found several of his toes had been frostbitten. The next morning they struggled on, sometimes on all fours, wolfing down handfuls of raw oatmeal as they went. Their fatigue was such that it took all their efforts to keep from falling asleep whenever they stopped to rest. After a battle of 10 hours, they reached the safe refuge of the Iron Store, on Burns Plains below Mount Arrowmith, about two hour’s walk to the east, and only five months before it burnt down. They slept the sleep of exhausted men until midday the next day. Laughton later described the journey as ‘the toughest experience I have ever had, and had not my mate Tasman Johnson and myself been pretty hard we must certainly have gone down under the constant strain’.

Many prospectors possessed an intimate knowledge of the regions they worked, but were unable to write lucid reports. But Laughton went beyond being just a prospector. He submitted well-thought-out and perceptive descriptions of the country through which he passed. He was a great believer in the mineral and timber prospects of the Frenchmans Cap region, and Laughton’s reports probably contributed to the decision to upgrade the Old Jane River Track in 1935.

Beyond prospecting, Laughton was taken with the beauty of the Frenchmans Cap region. ‘I have no hesitation in saying that this range is the most spectacular in Tasmania, if not Australia,’ Laughton informed the Chief Inspector of Mines, ‘and will become most famous with mountaineering tourists.’135 ‘Laughton’s Camp’ on the banks of the Loddon River was a familiar landmark to Jack Thwaites and other early bushwalking parties of the 1930s. They all knew of Laughton’s work and held him in high esteem.136 Today, his name is remembered in Laughtons Lead: that section of the Frenchmans track which connects the Loddon Plains with the rainforested slopes of Philps Forest.

Sydney Laughton and the other prospectors who went out on sustenance allowances were tough and resourceful men. They were the very epitome of the Tasmanian bushman of the early 20th Century. Their knowledge of the bush and of the Frenchmans Cap region would never be equalled in the years that lay ahead. But their kind was fast disappearing.

Nicoles Needle

Geoffrey Chapman and Mac Urquhart were good friends and seasoned bushwalking companions. Despite a deceptively slight build, Mac Urquhart was a powerful and determined walker. Both men had made early trips into the Southwest. It was inevitable that they would climb Frenchmans Cap. Chapman made a tentative probe in 1931 with Doug Anderson. Mac Urquhart had planned to join Davern and Anderson in 1932, but his planned rendezvous was forestalled by bad weather.

Finally, in February of 1935, Chapman and Urquhart successfully led a party to the summit of Frenchmans Cap. Details of their journey, however, remain sketchy. Perhaps the most interesting feature of the trip is that the party included a mysterious French girl, known to us only as ‘Nicole’. Chapman and Urquhart later named Nicoles Needle, a strikingly symmetrical shaft of columnar quartzite near Sharlands Peak, after her. Fittingly, given her French nationality, Nicole was the first woman to climb Frenchmans Cap, before mysteriously disappearing into the depths of time.

Nicoles Needle. (Simon Kleinig)

However, the soaring column of Nicoles Needle continues to be a major attraction to visitors to Frenchmans Cap. Its name came into use soon after Chapman and Urquhart’s return, when a photograph of ‘Nicole’s Needle’ appeared on the cover of the Mercury Pictorial Annual, 31 October 1935.

Fred Smithies’ fascination with Frenchmans Cap continued. He was one of the first people outside of the Hobart Walking Club to follow Philp’s Track. Smithies wrote to J. E. Philp requesting route information, and also to Aubrey Davern. Both were happy to oblige. ‘If you want to use our cave for shelter (we’ve left some wood there) you will recognise the ridge you came up with Pitt from the top,’ Davern informed Smithies.137

Fred Smithies and a number of friends from Launceston made a trip over the Christmas of 1935. The party included Reg Hall, a Launceston lawyer whose name would later become synonymous with the Walls of Jerusalem region. On this trip Reg carried a .22 rifle and sling in the hopeful expectation of shooting live game for their meals. Given the scarcity of game in the region it is doubtful whether Reg found it worthwhile hauling an entangling firearm along an overgrown bush track.

Today, the crack of a rifle echoing across the ranges at Frenchmans Cap would be both an illegal and unthinkable intrusion upon an otherwise pristine landscape. But in the early decades of the 20th Century, a hunting rifle was seen as a perfectly legitimate accessory to any bush trip. Other parties carried firearms for hunting into Frenchmans Cap around this time, though the practice appears to have disappeared by the early 1940s.

The party also included Archie McIntyre, Hector Boyd, Phil Waterworth, Joan Thorold, Betty Stabb and Peggy McIntyre.The latter two would become Mrs Reg Hall and Mrs Phil Waterworth respectively. The women of the party shared the combined honour of being the second, third and fourth women to climb Frenchmans Cap.

It was during this 1935 trip that the party was surprised to observe a lone figure approaching their camp at Lake Tahune. As the figure drew closer, they could see it was a man curiously dressed in a dark, pin-striped suit and hat. He was carrying a small leather case, which presumably contained his provisions for the trip. The man simply raised his hat to the party, wished them all good morning and walked briskly on, leaving them both bewildered and mystified by the encounter.

Reg Hall’s party, December 1935. Left— Archie McIntyre, Hector Boyd, Betty Stabb, Phil Waterworth, Peggy McIntyre, Reg Hall, Joan Thorold. This photograph was taken by another member of the party, Fred Smithies. (Liz McQuilkin).

Archie and Peggy McIntyre drew on a strong family heritage of pioneering. Their maternal grandfather, Professor T. W. Edgworth David, had served with distinction as professor of geology at Sydney University. He journeyed to the Antarctic with Shackleton’s Nimrod expedition in 1908, and made the first ascent of Mount Erebus. The Erebus party also included a protégé of Edgworth David, the young Douglas Mawson. Edgworth David served with the Australian Tunnelling Corps in World War One, and was commanding officer to Major Leslie Coulter, DSO, who had climbed Frenchmans Cap with Charles Whitham’s party in 1914.

Reg Hall was a highly inventive man who designed everything from mountain chalets to houses, motor cars to yachts. Above all else, Reg loved the outdoors. In any given year, his time was divided between bushwalking in the summer, skiing the slopes of Ben Lomond in the winter, and sketching or planning anytime in between. Nothing delighted him more than designing bushwalking and ski gear. In later years Reg Hall’s daughter, Liz McQuilkin, recalled a busy domestic scene:

I grew up with a portable canoe sometimes assembled in our living-room; steam coming from the kitchen as Reg bent the cane near a boiling kettle to make a frame for his pack; maps and sketches everywhere, even on the loo paper; Reg sitting at the dining room table operating a hand-wound Singer sewing machine and making a tent, or clothing, or little calico bags for flour and sugar. He had a lovely old draughtsman’s table near the large window in our living-room and there he sat when he was home, designing or calculating or plotting trips.138

Reg Hall was highly proficient at drawing maps. He devised a lightweight mapping board with clips for holding down paper and a ruler along the base. Reg took this mapping board with him on all his early bush trips. On returning to Launceston in 1935, he drew a detailed map of the Frenchmans Cap region using the information he had recorded on his mapping board. Other maps had been drawn by Fred Smithies, and later by Angus Love, Ron Smith and Alan and David Richmond, all based on J. E. Philp’s 1910 map.

The margins of these maps often contained annotations describing the nature of the terrain. Some even had cartoon drawings of features such as Barron Pass and Pine Knob to help the traveller find his or her way. There were precise instructions and drawings on how to reach Daverns Cavern, which continued to be an opportune overnight stay for early parties whenever the weather threatened.

Reg Hall’s 1935 map was a significant step forward in that it showed heights, contours, contour intervals and bearings, together with detailed notes on vegetation and geology. Though not widely distributed, it was the best map of its period and was only improved upon with the advent of aerial survey maps after World War Two.

With improved access along the Jane River Track, increasing numbers of bushwalkers visited Frenchmans Cap. In January 1936, Jock Turner made his third visit in three years. Rhona Warren and Leo Luckman, early members of the Hobart Walking Club joined him, together with newly-weds Jack and Cecilie Thwaites.

It was to be was another Frenchmans trip marred by bushfires, with smoke obliterating views for much of the way. The fires were so close that the party was actually threatened on a couple of occasions. It was on this trip that Jack Thwaites cairned what he considered to be the best route to the summit of Frenchmans Cap. He reviewed the route eight years later and concluded that it still represented the most straightforward approach to the summit. Apart from a few deviations to protect sensitive areas of moss and alpine flora, Jack Thwaites’ 1936 route is still that followed by walkers today.

Leo Luckman was tempted to climb Clytemnestra, but after a short reconnaissance decided against it. Jessie Luckman believed the first ascent of Clytemnestra was made a few years later by another Hobart Walking Club member, Brian New.139 The party returned to the highway over the Raglan Range, the second time only that this route had been followed. Jetty Lake was named on the way, for an unusual jetty-like prominence jutting out into the lake. Jock Turner led the way, having pioneered the Raglans route three years earlier with Aubrey Davern.

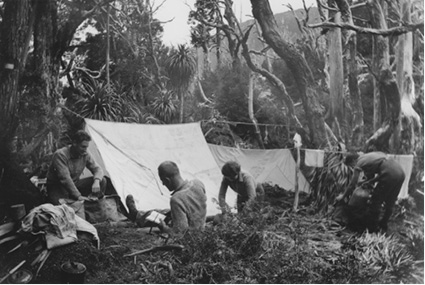

An early camp at Lake Tahune. Left—Leo Luckman, Jock Turner, Rhona Warren, Cecilie Thwaites, January 1936. (Jack Thwaites)

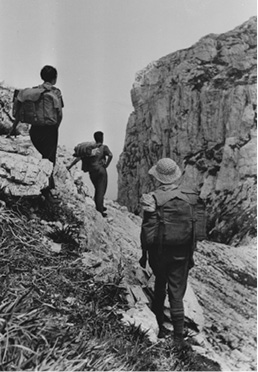

At North Col, January 1936. Left—Cecilie Thwaites, Leo Luckman, Rhona Warren. (Jack Thwaites)

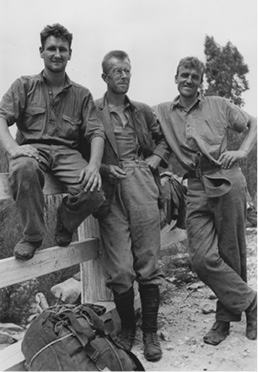

Journey’s end. Resting by the West Coast Road. Left—Leo Luckman, Jock Turner and Jack Thwaites. (Jack Thwaites)

Thylacines at Frenchmans Cap

Fred Smithies made several journeys to Frenchmans Cap during the 1930s. One of his most unusual trips was triggered by reports of a thylacine, or Tasmanian Tiger,140 at the Cap a few years earlier. Several parties were convinced they had seen thylacine footprints around the shores of Lake Tahune. One of the most convincing reports came from Tourism Director E.T. Emmett. In 1934, he was certain he heard a thylacine brush past his tent on its way to the lake, where he ‘heard him greedily lapping up water’.141 Over Christmas 1935, Fred Smithies joined the party of Reg Hall, which discovered thylacine prints in the sand around Lake Tahune. The following morning they found their ‘breakfast bacon’ had been taken after being left hanging from a tree overnight.142 The problem with these stories was that they all fell short of an actual sighting.

Fred Smithies found reports of the thylacine at Frenchmans Cap irresistible. He immediately embarked upon a quest to photograph the rapidly disappearing marsupial. In addition to his pack and photographic equipment, Fred somehow managed the awkward burden of a caged chicken (apparently named Henrietta). This was intended to act as a photographic lure for the elusive thylacine. Fred planned the whole operation with precision and kept a patient lakeside vigil over several nights. It was all to be in vain, however. Fred returned with neither a photograph of the thylacine nor the chicken, the latter suffering the final indignity of providing Fred’s party with their last dinner in the bush.

By the 1930s, the Fauna Board knew the thylacine was under serious threat. ‘Will you please ask all men working on the Jane River Track to keep a good look out for any wild tigers,’ the Director of Public Works advised the foreman of the work party. ‘The Hon. Minister states that the Fauna Board is most anxious to know whether or not the animal is extinct.’143

In 1937, the Fauna Board became serious in its efforts to find the thylacine. That year it sent out the first of its search parties, led by Trooper Fleming. Arthur Fleming was a powerfully-built and experienced bushman capable of carrying very heavy loads. Accompanied by prospector L. Williams, the pair combed the remote ranges between the Raglan Range and Frenchmans Cap. They reported a number of tracks and were certain a breeding population of four thylacines existed in the area. Frustratingly, Fleming was unable to report an actual sighting to the Board.

The Fauna Board was encouraged by Arthur Fleming’s optimism and enthusiasm. In late 1938, Fleming returned to the region with a party of six, including two miners from the Jane River goldfield and Michael Sharland. For 11 days, the party searched the country between the West Coast Road, the Jane River and Lightning Plains.

Michael Sharland was a well-respected journalist, conservationist and field naturalist. In addition to serving on the Fauna Board, he was a member of the Scenery Preservation Board and Honorary Ornithologist to the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery. His popular weekly articles on Tasmanian flora and fauna, penned for the Mercury under the name of ‘Peregrine’, endeared him to several generations of Tasmanians. Near the entrance to Calder Pass, the party found the first positive signs of thyalcine activity in the Frenchmans Cap region.

We saw the first definite imprints of Thylacine. In the mud on the track that we were following the animal had made a splendid impression. Claws and ‘pads’ were delineated clearly ... The manus, or ‘hand’ of Thylacine leaves a distinct impression, in which five digits and claws are generally visible ... It was obvious that the animal had passed that way quite recently.

Imprints were also found and plaster casts taken along Thirkells Creek, and near Stannard’s grave close to the Jane River. These plaster casts were later sent to Sydney and were positively identified as thylacine prints. The party also found more imprints along Erebus Rivulet and beside the banks of the Loddon River.144 One night in the Jane River hut, Michael Sharland recorded that ‘one had been inquisitive enough to encircle the place and come near to sniffing at the chinks between the slabs that formed the wall’.145

Thylacinus cynocephalus. An 1863 drawing of two thylacines by John Gould from ‘Mammals of Australia’. (National Library of Australia)

The respected zoologist David Fleay was another who explored the region in 1945. His party included Michael Sharland and the indefatigable Arthur Fleming. They concentrated on the Jane River area, which was no longer occupied by miners and had been heavily snared for the past four years. They found a large number of snares set by trappers, and worse still, poison laid to rid their traplines of devils. Tragically, these snares and baits probably accounted for the struggling thylacine as well.

The huge influx of piners, miners and packers into the Jane River during the 1930s and 1940s had a huge impact on the local ecology. All the impedimenta of bush camps — men, dogs, snares and fires — severely compromised the chances of survival for the rapidly diminishing thylacine. Despite all these obstacles, traces of the thylacine appear to have been found in the Frenchmans Cap region up until at least the 1940s. Dr Eric Guiler, a former reader in zoology at the University of Tasmania, devoted many years to thylacine searches. All these people committed themselves to quite intensive and exhaustive searches.

Why did the thylacine disappear so quickly from Frenchmans Cap? This remains largely a matter of conjecture, but there are several clues worth investigating. For a start, it is clear the region was never the preferred habitat of the thylacine. Its prey was found in greater numbers elsewhere in Tasmania. The thylacine survived longer in the harsh country around Frenchmans Cap only because the very remoteness of the region offered it some protection.

In the settled areas — its traditional hunting grounds — the devastating effect of a bounty, combined with fear, the fencing of properties and a deliberate campaign of baiting, had effectively wiped out the thylacine. Only in the remote west was the species able to hang on by a slender thread in a forested region dominated by a harsh climate and mountainous terrain.

But what really crippled the chances of survival for the thylacine was bushfire. Over the first four decades of the 20th Century, the Frenchmans Cap region was regularly raked by fierce bushfires. These fires, many purposely lit, seriously depleted game on which the top predator depended for its livelihood. Later, with the opening of the Lyell Highway, the region suddenly became accessible to prospectors working the Jane River goldfield, and to a permanent team of road workers and patrolmen. This last intrusion by humans dealt the luckless thylacine the final blow.

It now seems likely that thylacines did venture as high as Lake Tahune, as reported by several parties in the 1930s. A parallel example of high altitude habitat is that of the platypus at Frenchmans Cap. It was frequently seen in Lake Vera but never reported at Lake Tahune. It came as a complete surprise, therefore, when a platypus was seen and photographed swimming in the lake in February, 2006.146 There have been regular sightings in the years since.147 Amazingly, the platypus appears to have reached the lake by swimming and scrambling up Tahune Creek from the depths of the Franklin Gorge. The platypus follows waterways and is also known to travel across land. It is found in all the streams of the Frenchmans Cap region. The thylacine was officially declared extinct by the Tasmanian Government in 1986.

Fred Smithies’ ongoing legacy

The first known colour movie of a trip to Frenchmans Cap was taken by Fred Smithies. In 1936 he was joined by three others, including Reg Hall. Fred’s images show the party climbing the Cap — the hard way, by scaling the cliffs above North Col — and baking bread in their camp oven beside Lake Tahune.148 The end of the 1930s marked the last of Fred Smithies’ trips to Frenchmans Cap. He was now in his fifties, though by no means past his prime. Fred continued walking all his life, but now he moderated his big, tough bush trips with less demanding undertakings and ski activities with the Northern Tasmanian Alpine Club. He also concentrated more on administrative, civic and family responsibilities.

Fred had been an adventurous and determined early bushwalker, but he was also a man who knew his limits. He was under no illusion; as an insurance agent from Launceston, he could never come to know the bush like Cliff Bradshaw or Paddy Hartnett. Fred always made his toughest journeys in the company of experienced bushmen.

Some people claimed that Fred exaggerated the hardships of his journeys. If he did, it was probably because he found it difficult to suppress his enthusiasm and passion for places such as Frenchmans Cap. There is no question that Fred’s early trips to Frenchmans Cap were tough, pioneering undertakings that few people would have even contemplated at the time.

Fred enjoyed working with other people, but he was also a shrewd and canny self-promoter. His famous lantern slide lectures, many devoted to Frenchmans Cap, made him a popular figure throughout Tasmania.

Fred displayed an early concern and understanding for Tasmania’s wild places. ‘As a general rule, nature can be relied upon to repair her own ravages,’ Fred wrote in the Saturday Evening Express on 25 September 1937. ‘The most ruthless and effective destruction agency of all, however, is man. Wherever civilisation penetrates, the question of forest conservation and soil erosion sooner or later becomes an acute problem.’ Fred spoke out strongly about forest conservation, issuing a rallying call which has echoed down through the decades to the present day. ‘Widespread destruction of forest areas has occurred and is still going on. On every hand we see the ruthless removal of trees and undergrowth.’

Fred Smithies left a rich legacy for future generations to absorb through his photographs and newspaper articles. His newspaper articles in particular provide a wonderful record, and not only of his many bush journeys. They also provide an opportunity for us to gauge the level of community awareness towards wilderness areas during the decades of the 1930s and 1940s.

‘I’d like to have another hundred years ahead of me, with full active strength’, Fred explained in the final years of his life. ‘I’d like to see other parts of the world, but that not being possible I did determine to see as much as I could of our own little state. Every mountain offered a challenge, every hidden lake an irresistible lure and every waterfall an inspiration.’

Later trips to Frenchmans Cap

A number of attempts to climb Frenchmans Cap were made in 1938. Alan Richmond and Max Poulter camped at Lake Tahune, but could get no higher. Battling stormy January weather, they eventually descended to the welcome shelter of the Abels’ log cabin on the south Loddon Plains to dry out.

The same year, a party of five climbed the Cap in difficult conditions — rain, sleet and hail — ‘a very easy climb’. On the track they passed ‘four chaps from Hobart’ and shared their Lake Vera campsite with another two parties, one comprising seven members. ‘Tomorrow we are going to L.St Clair to recuperate,’ Geoffrey Dineen wrote to his mother, ‘after three days of travel through most strenuous country (knee deep mud and slush).’149

Abels’ Hut. A packers hut on the south Loddon Plains, January,1938. (Alan Richmond).

Fifteen year-old David W. Wilson made three ascents of Frenchmans Cap in 1938. He was spending his summer school holidays walking in the Du Cane Range and working for Bert Ferguson at Lake St Clair, ‘waiting on tables and chopping wood’.150 When three ladies staying at Fergy’s camp announced they were making the trip to Frenchmans Cap, Fergy instructed David: ‘you’d better go along to light the fires and chop the wood for them.’ David Wilson returned twice in 1938, for an Easter trip and again over Christmas.

Angus Love joined David Wilson as members of the party in Easter, 1938. Angus worked as a young draughtsman for the Lands and Surveys Department, and later drew a detailed map of the Frenchmans Cap region. He also completed a pedometer traverse of the entire route, recording a distance of 14.5 miles, from the West Coast Road to the summit. It was on this trip that Angus Love suggested the name ‘North Col’ for the narrow connecting ridge between Lions Head and Frenchmans Cap.

From the 1960s, the moderating effect of global warming began to be felt at Frenchmans Cap. While average rainfall appeared unaffected, temperatures began to rise and snowfalls were not as heavy nor as long-lasting as in the past.

Parties to Frenchmans Cap in the early days had a difficult time with the weather (see ‘Prospector’s sustenance allowance’, page 127). Many managed to get no further than Lake Vera. Heavy rain flooded campsites and the prospect of swollen rivers caused many to beat a hasty retreat across the waterlogged Loddon Plains to the safety of the West Coast Road. Other parties struggled to the top of Barron Pass and even to Lake Tahune, only to be met by such wild weather that withdrawal to lower country was the only safe alternative. Before huts were built in the region campsites were often wet and windy, and many people returned without even a glimpse of the mountain. ‘I made eight trips to the Frenchman,’ Robert Mather recalled in later life, ‘got to the summit five times, saw the view twice.’151

The Jane River goldfield

It was Robert Warne’s discovery of gold that precipitated the Jane River ‘rush’. Small amounts of gold had been found near the Jane since 1894. In that year, H. Burrows discovered alluvial gold in a small creek (now named Burrows Creek) which flows into the Jane River. Since that time, prospectors continued to wash the gravels with enough colour showing in the occasional dish to ensure others were attracted to the region.152

Warne operated a successful fruit and vegetable business at 343 Liverpool Street in Hobart. One day, an acquaintance happened to mention in passing that he had found a small amount of gold near the Jane River. Far from being infected with ‘gold fever’, Warne merely made a mental note of the fact. His thinking was to visit the Jane at some indeterminate date in the future, ‘when I had the time to spare’.

Warne found the time in March 1934. Heading south on the track towards the Jane, he passed Jack Thwaites, E.T. Emmett and Des Giblin. The trio was returning from a successful trip to Frenchmans Cap, and stopped briefly to chat with Warne.153 But success for Robert Warne came spectacularly 17 months later.

On Wednesay, 7 August 1935, he was working alone when he made the discovery. ‘I took a dish full and washed it carelessly, then swung it round — the light was bad and I couldn’t believe my eyes — surely that couldn’t be gold, so picking up a piece, I bit it, and the bite said gold ... To say that I was pleased with the result would be a gross understatement.’154

Warne was no solitary prospector working away in detached isolation. Others were scratching away too, including the Abels, who had been prospecting the area for the past 12 months. Warne, however, was the prospector fortunate enough to make the initial discovery.

One of the tasks required of the Queenstown-based Inspector of Mines was to furnish a report each month on gold recovery. Most of the gold in the west came from Mount Lyell, supplemented by small amounts of alluvial gold found in creeks near Queenstown, Linda, Mount Jukes, and a handful of other locations. A conspicuous absentee from these monthly reports was the Jane River area — Robert Warne’s discovery had taken the Mines Department completely by surprise.

‘I have been informed this evening that [Charles] Abel hurried back today to secure his ground and that a man named Ward or Warne, who has taken out a fair quantity of gold, had gone to Hobart to apply for a reward claim,’ the Inspector of Mines hastily advised his superior.155 The ‘rush’ had begun. Within 12 weeks, there were 33 men prospecting claims in the region.

Bushman and snarer Paddy Hartnett found the largest nugget at the time, ‘on his claim in the Reward Creek, weighing 17 dwts. 21 grains’.156 Another bushman, Milford Fletcher, worked a joint claim between 1935 and 1938. In the following years, Fletcher, a farmer, bushman and track cutter from the south-west, would have a continuing association with Frenchmans Cap.

Men attracted to the goldfield came from a cross section of society. Many were prospectors working their way habitually around the west coast. Others were bushmen, piners and miners, taking time off work to take out leases in the hopeful expectation of a big find. Finally came the opportunists and refugees, smarting from the effects of the Great Depression, hoping for a change in their luck.

The miners built rough bush huts for themselves. These were usually hastily thrown together slab affairs which suffered badly from the ravages of the weather. Despite the isolation of the goldfield, ‘packers’ brought in a staggering quantity of gear, much of it quite superfluous to the miners’ daily needs. And all of it had to be carried in. The hardy men known as ‘packers’ acted as beasts of burden, and many managed to make a living carrying heavy loads into the goldfields settlement.

‘Some of the more prosperous members of the settlement pay men to ‘pack’ for them at a charge of a 1/– a lb,’ stated a newspaper of the day. ‘Some of the weights carried are amazing. A. J. Best is said to hold the record for packing to this particular field. A pack which he once carried the 23 miles, tipped the scales at 140 lb net. Weights of up to 100 lb [over 45 kg] are carried in almost daily.’157

The New Jane River Track

In 1939, a new track was completed to the Jane River goldfield. Despite the money spent on the Old Jane River Track in 1935, this track had suffered one serious drawback: it could not accommodate the pack horses necessary to carry heavy loads of supplies down to the goldfield.

The New Jane River Track, begun in 1936 and completed in 1939, was located three kilometres east of the Old Jane River Track. The track extended from the Lyell Highway south for 24 km to the Jane River goldfield. A paling hut, known as the Jane River Dump, was erected nearby. This hut was later upgraded to a more durable, though less appealing structure of concrete slab construction, which stood for many years. The new track was a vast improvement on the Old Jane River Track, with good bridges built over the Franklin, Loddon and Erebus Rivers. It was now possible to take pack horses, and later vehicles, down to the goldfield.

A common and erroneous belief at the time was that the Jane River gold must have originated from a large lode somewhere in the area. In October 1935, the Acting Government Geologist was convinced that ‘the gold had not travelled far, and the load or vein should be found near the alluvial gold’.158 But all the gold that was ever won at Jane River was alluvial and small in quantity. Most of the gold was found within six years of Warne’s discovery. Only a year after Warne’s success, the ‘rush’ had waned, and the number of men working the field had been reduced by half.

There was gold near the Jane, but it was never to fire the imagination nor rival the goldfields of Victoria and New South Wales. The Jane River goldfield required patience and persistence, and a long and methodical system of working claims. The outbreak of World War Two left the goldfield practically deserted, and after the war, a buoyant economy offered men full employment and high wages. The uninviting prospect of eking out a doubtful living ‘roughing it’ on hard rations in an isolated region in the west was distinctly unappealing.

Nevertheless, Warne only abandoned the goldfield when he sensed his claim was nearly exhausted and his health started giving him problems. In 1952, at the age of 61, he turned his back on his Reward Claim for the last time. In the 18 years since his 1935 discovery, Robert Warne had made forty-five trips to the goldfield and taken 744.5 ounces of gold. He was the most persistent and successful miner at the Jane River goldfield.

By 1974, the world price for gold had risen to $118 per fine ounce. This, as much as anything, caused John Bennetto to acquire all the surrounding leases at the Jane River goldfield. These he consolidated into one lease and worked it until 1990. Meanwhile, the New Jane River Track was subject to repair and neglect as interest in the goldfield waxed and waned.

In 1989, a government ruling put an end to all mining in World Heritage areas. At Jane River, John Bennetto was required to rehabilitate the entire area he had worked for nearly 30 years. The rehabilitation was not wholly satisfactory and some of Bennetto’s men even worked the goldfield illegally for some years.

By the turn of the millennium, dilapidated bridges, tree falls and bush left the New Jane River Track impassable for vehicular traffic and difficult for even bushwalkers to follow. The destruction of old tracks in Western Tasmania was rampant during the 1960s and 1970s. Many tracks, railways and tramways were obliterated when new roads were bulldozed over existing tracks, or creeks and rivers were forded in order to by-pass existing bridges. This wholesale destruction of heritage was carried out with the full approval of government. It only ground to a halt after an outcry from bodies such as The Wilderness Society, and Bob Burton in particular.