20 The First Rock Climbers

Every new route on Frenchmans Cap is a voyage into the unknown.196

The explorer T. B. Moore once described the cliffs of Frenchmans Cap as ‘grandly sublime and indescribably beautiful’. He was also convinced in 1887 that nothing on earth could ever scale them. By the early 1960s, however, the sport of rock climbing had evolved to such a point that T. B. Moore’s words were no longer valid.

Rock climbing marked a completely new direction for exploration on Frenchmans Cap. Scaling the sheer cliffs of the Cap went beyond the preserve of a handful of enthusiasts indulging themselves in an extreme sport. It introduced a new and exciting era of exploration to the mountain, as important and groundbreaking as any since Europeans first began visiting the peak, 130 years earlier.

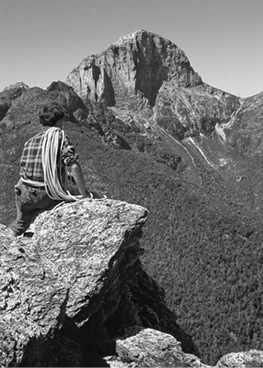

The Challenge. Mike Douglas surveys Frenchmans Cap from on the Main Range, January 1963. (Peter Sands)

Before the first rock climbers, scrambling to the summit of Frenchmans Cap was, for most people, a relatively straightforward undertaking. As early as the mid-1930s, the best route to the summit had been clearly established. It followed the mountain’s line of least resistance, weaving through small cliffs to the safe, upper ledges of the peak. It was true that Frenchmans Cap, like most Tasmanian peaks, had a ‘sting in its tail’ — a high, uncomfortable ledge — but with this minor obstacle surmounted, the remainder of the climb presented no real difficulties for the average bushwalker.

Rock climbing brought with it a wave of renewed interest in Frenchmans Cap. Exploring the massive rock faces of the peak and its environs offered fresh challenges unequalled on any other Australian mountain at the time. The arrival of the first rock climbers in 1962 may have been the dawn of a new era on Frenchmans Cap, but rock climbing itself was hardly a new sport.

In Europe, the use of alpenstocks, ropes, belays and climbing techniques had been practised for over a hundred years. Stand-alone rock climbing, however, appears to have had its genesis in the late 19th Century, evolving gradually from an important ingredient of alpine ascents to a quite distinct athletic activity. By the 1960s, the development of both climbing techniques and equipment allowed rock climbers to go to places undreamed of in the past.

The first recorded climbs on Frenchmans Cap were made over Easter 1962, by Tasmanians Mike Douglas, John Fairhall, Peter Sands, Robert Lidstone, Robert Hosking and Doug Cox. These climbs were made on the north-west wall — a series of buttresses, towers and rock faces — and its near neighbours, rising above Lake Gwendolen. That Easter, John Fairhall and Mike Douglas also completed the first climb of Deceptive Gully on the Tahune Face. A brave attempt on the main face of the Cap, near De Gaulles Nose, was undertaken by Doug Cox and Mike Douglas, who climbed about sixty metres before abseiling down to the scree at the foot of the Cap. Many of the new routes on the mountain were named to enhance the French character of the mountain.

It was also over Easter 1962, that Lidstone and Sands, the two most accomplished Tasmanian climbers of the day, pioneered a route called North East Passage. This led between Terrays Tower and the Tahune Face. On the upper section of the climb, Lidstone and Sands worked their way up the top section of the East Face, a remarkable achievement at the time, and verified 10 years later when old pegs were found on the upper part of the route.197 Peter Sands recalled the climb years later: ‘Our equipment was very rudimentary compared to nowadays, and our footware was either sandshoes, or leather-soled walking boots with nails and clinkers around the edge. We hadn’t got a clue what we were going to do, where to start, how long it would take, or what to expect. There was just an idea of finding some route and going for it.’

The climb was made with an overnight bivouac high up on the east face. ‘It was getting dark now, and of course we were in the deep shade of the mountain itself. I’d had a nice pendulum fall carrying that damned pack around a huge and somewhat slippery chock in the gully, and it was my turn to carry it again from a belay at the notch. Bob led upwards, and by the time he’d found a suitable bivouac spot it was really dark.’

We were now high up on the edge of the east face, which curved outwards a bit so we sort of looked out on to it, not along it. The full moon soon rose and this wall just glowed like the screen of a drive-in theatre ... it was an awesome experience! We were ‘high’ on the situation we found ourselves in, and very little sleep was had in that inner and outer brightness! We were on a narrow ledge with some damp vegetation. We’d belayed ourselves to several pitons — no way were we trusting ourselves to just one — and were in our sleeping bags. Morning came and we completed the climb. This was one giant lump of white quartzite! I remember steep, smooth rock that was quite damp in places, and cold under the fingers. With the sun now on us, and the view expanding as we ascended the last few pitches, it was a peak experience in more ways than one. Sometimes there are occasions in a young man’s life when it’s best his mother does not know what he’s doing, and this was one!198

It was nearly three years later before the first full climb of the main face was completed. ‘The last 1,000 ft is really something,’ Bryden Allen told Mercury reporters in early January, 1965. He and Jack Pettigrew had just scaled the south-east face of Frenchmans Cap. It was the first successful ascent, after five previous attempts had proved unsuccessful; three by Tasmanian parties, one from interstate, and one by an English party.

‘Two-thirds of the way up the face there is a major overhang, but we were very lucky to find a thin crack leading to the left which we followed with difficulty. There is not much elation when you are so tired after a climb like this.’199 Bryden Allen and Jack Pettigrew named their route ‘A Toi la Gloire’ (more commonly referred to today as the easier-pronounced ‘The Sydney Route’). It was to become the most sought-after route on Frenchmans Cap.

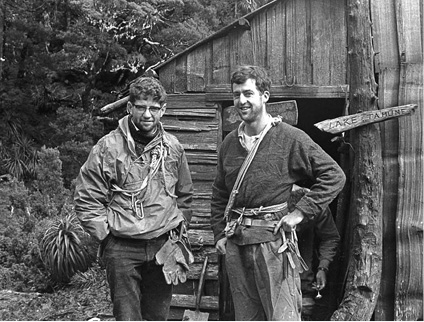

First honours. Bryden Allen (left) and Jack Pettigrew outside old Tahune hut after a recce for their first ascent of the main face of Frenchmans Cap in January 1964. (Jack Pettigrew)

The challenge of Frenchmans Cap as a fresh field for exploration was attracting rock climbers from all over Australia. Three years after the first ascent of the main face, an energetic group of mostly Victorian climbers descended on Frenchmans Cap: Chris Dewhirst, John Fahey, Philip Stranger, John Veasey, Chris Baxter, Val Kennedy, John Moore and John Ewbank. Over eight productive days in February 1968, these climbers pioneered a number of new routes: The Chimes of Freedom, Valerie, Waterloo Road, Fleur-de-lis and Tierry le Fronde. Routes by later climbers included The Great Flake, The Lorax and The Ninth of January.

In January 1972, the first climb of the Conquistador route took Chris Dewhirst, Ian Ross and David Neilson over 18 hours of intense, concentrated climbing. It was a daring achievement — an assault directly up the middle of the daunting east wall of the Cap. The climb also necessitated an airy overnight bivouac halfway up the face.

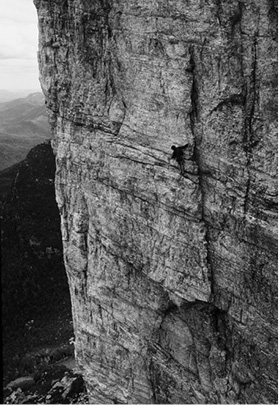

In the great white silence. Dave Jenkins following the second pitch on ‘The Ninth of January’ (grade 19) on Terrays Tower, January 1995. (Pete Steane)

‘It was a sunrise without equal,’ wrote David Neilson, reflecting on the dawn of the next day, ‘for we had bivouacked in the centre of the most impressive rock face in Australia — the east face of Frenchmans Cap ... As I stepped off the ledge I was immediately aware of the scree slopes several hundred metres beneath my feet. The climbing required considerable concentration, however, and I was soon oblivious to the exposure as I searched for any small holds on the otherwise smooth rock.’200

Chris Dewhirst wrote, ‘The sky’s blueness is the deepest ocean. The golden sun warms the black lakes below us. White quartz shines like Michelangelo’s David ... The wall above [led by David Neilson] looks easy. It turns out to be one of the most unprotected, dangerous and difficult pieces of climbing I’ve done ... The rock is greasy, the holds small and the strata down-sloping. It becomes a rope-stretching, nightmare lead.’201

Few new routes were opened over the next decade until 1982, when Kim Carrigan and Evelyn Lees pioneered The Great Flake on the east wall. Kim Carrigan returned in 1983 with Mark Moorhead, and climbed De Gaulles Nose, the thin arête (a knife-like ridge of rock) dividing the soaring south-east and east faces, and the most difficult route on the mountain to date.

Between the late 1980s and the mid-1990s, Tasmanian Peter Steane was a particularly active climber at Frenchmans Cap, with partners Garn Cooper, Doug Fife, Roxanne Wells, Nikki Sunderland and Colin Moorhead. Peter Steane added 15 routes over this period, the most notable being The Lorax, between the Great Flake and Conquistador, which he climbed with Garn Cooper. In 1997, Peter Steane and Colin Moorhead climbed through the main roofs that cap the Tahune Face, along a route later named Ground Rush. Beyond the Cap itself, numerous routes were climbed on other peaks around the curving, rocky horseshoe of the Main Range: Clytemnestra, Philps Peak, White Needle and Sharlands Peak.

Rock climbers face a demanding day’s walk through difficult terrain just to reach the foot of the peak. The average climber arrives at Tahune Hut with a pack weighing at least 25 kg. Typically, this contains a full rack of hardware, two 50 m ropes (9 mm diameter), and personal climbing gear — harness, climbing boots, helmet — and food for a week. Some Tasmanian climbers cache their climbing gear at Frenchmans Cap, then make fast, lightweight trips to the mountain whenever good weather is forecast.

Then there are expedition-style parties, often from the mainland, which encumber themselves with so much gear that they have to ferry loads between huts. At the other end of the scale, highly-skilled and experienced climbers take just one thin rope (8mm diameter) and a minimum of hardware, and climb with an acceptable degree of safety at a level below their real capabilities. One such climber, John Fischer, made a rapid, lightweight trip to Frenchmans Cap in February 2010.

The thought of soloing Frenchmans in a day kept circling in my mind. I decided to do it early February and started watching for a weather window ... Saturday morning I woke up late and left the Highway at 7.21 a.m. I took a couple of thermal shirts, a pair of shorts, shoes, chalk, two candy bars and a banana. No water bottle as 300 cm of rainfall a year makes it pointless. I got to Tahune before noon, but had an ‘epic’ climbing the Sydney route, so retreated and climbed Chimes of Freedom (17) instead. It took four hours for the climbing, and I got back to the ranger station at the Highway at 9.18 p.m.202

The Ivory Tower. The soaring east face of Frenchmans Cap as seen from East Col. (Grant Dixon)

Today, Frenchmans Cap has over seventy recorded routes on its walls and faces, including the surrounding peaks. It remains a true mountain experience, and its long routes are highly-prized accomplishments amongst rock climbers.

As ever, the fickle Frenchmans weather frequently upsets plans. The cool southern face of the Cap, shaded for much of the day, numbs the fingers and even encourages the growth of patches of moss on the rock. Shattering by frost leaves loose rock in places, and the brittle nature of the Frenchman’s quartzite can result in the rock splitting into blocks when piton placements are driven. Far from detracting from the mountain’s appeal, many rock climbers see these challenges as further enhancing the overall experience of rock climbing on the mountain. Frenchmans Cap is regarded by many as the foremost wilderness climbing destination in Australia.

There are still plenty of challenges for rock climbers at Frenchmans Cap. Stephen Bunton said, ‘For those not daunted by mind-blowing exposure, the occasional rubble infestation or shaky hold, there remain hectares of rock to be caressed by chalky hands for the first time.’203

Chris Baxter, who took part in the first ascents of Waterloo Road, The Melbourne Variant (a variant of the Sydney Route), and La Grande Pump, amongst others, summed up the nature of rock climbing at Frenchmans Cap.

The atmosphere of Frenchmans Cap is hard to define. But there is certainly something different about climbing on a peak which is many miles from the nearest track or unsealed road let alone from civilisation. The weather is so notoriously bad that when the sun does shine the quartzite seems so much whiter, the distant ocean seems to sparkle even bluer, and the reflections on the alpine lakes all the more alive. You climb close with a friend in the vast white loneliness, the silence rushing up from that sombre, green, unfathomed bush, a thousand miles below.204

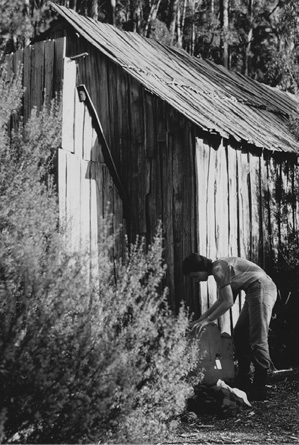

Kathy Fleming outside old Vera Hut, 1976. (Peter Fleming)

A hut for Lake Vera

Until the early 1960s, most bushwalkers going to Frenchmans Cap spent their first night at the head of Lake Vera. Camping here, using J. E. Philp’s original campsite, had been a tradition for over thirty years. However, as firewood at the top end of the lake became scarce, people began camping at the eastern end of the lake, where wood was more plentiful.

In early 1962, the Scenery Preservation Board finally gave approval for a second hut to be built in the Frenchman’s Cap National Park. The contract was given to Milford Fletcher, who enlisted the services of two Glen Huon men, W. R. H. Brown and J. G. McLeod. These men were skilled at building a hut from scratch, using natural materials. It turned out to be a miserable undertaking. During the 24 days it took to build the hut, it rained continuously. Nevertheless, the men worked on stoically, felling and splitting West Coast Peppermints (Eucalyptus nitida) close to the hut site.

The Mercury reported the completion of the new hut in June, 1962: ‘Seven Hobart Walking Club members waded through deep snow in bitter weather at the weekend to open “officially” the new bushwalkers’ hut at Lake Vera in the Frenchman’s Cap National Park. The walkers had to contend with falling snow and sleet as well as the snow underfoot along the 9.5 mile track to the hut from the Lyell Highway.’205

A member of that party, Barry Ford, recalled a cold journey: ‘We had to break the ice as we went across the Loddon Plains. We spent a miserable night in the hut. I think it’s the coldest I’ve ever been. We left billies of water inside the hut and they actually froze overnight.’206 Bruce Davis carried in a heavy movie camera to photograph the new hut and a few scenes along the track. Although the bleak weather made photography difficult, footage of the trip and of the new hut were televised a week later on the evening news.207

The hut had a number of ‘permanent’ residents. A family of swamp rats (Rattus lutreolus), possibly the long-tailed mouse (Psuedomys higginsi), and even the swamp antechinus (Antichinus minimus, also known as the little Tasmanian marsupial mouse, a dasyurid marsupial related to quolls), made a habit of finding their way into unsecured rucksacks. ‘Rastus the Rat’ became the subject of frequent entries in the hut logbook, including suggested methods of entrapment. The rat sightings extended over some years, suggesting that a number of generations, each of about 18 months’ duration, had lived in the hut.

An entertaining night at Vera Hut could also be spent by simply reading the hut logbook. The most obvious entries concerned the day’s crossing of the Loddon Plains. New visitors wrote long, witty and often exaggerated accounts of their first experiences of mud and river crossings. The old timers, having seen it all before, merely turned the pages of the logbook in reflection and quiet amusement.

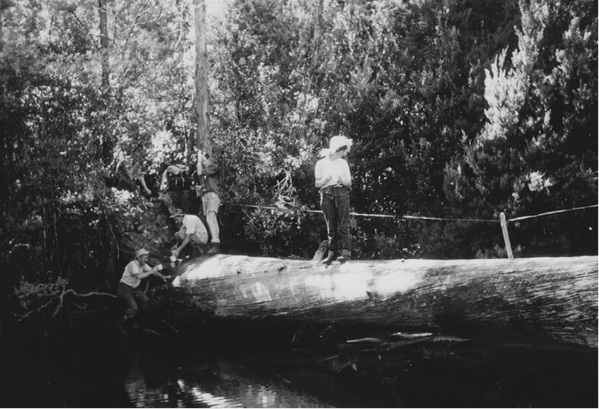

Log bridge over the Loddon River, 1976. (Peter Fleming)

After a few years, the hut began to leak badly. The split timber, used while still green, led to a serious shrinking and warping in the palings. ‘Leaks like a sieve’, was a frequent entry in the hut logbook of the 1960s. By the 1970s, the hut was leaking so badly that someone had even hooked up an old tent near the roof to stop rain getting into the bunks.