21 Bushfire!

… where once the steep mountain sides and ridges were clothed in myrtle and pine, much is now naked mud and ash.

The warning signs and build-up were ominous. Monday, 21 November 1966 was a hot and windy day throughout Tasmania. In Hobart, the temperature reached an uncomfortable 33 degrees Celsius, the hottest November day since 1938. On Tuesday, the temperature in Hobart climbed further to 36 degrees, the hottest November day on record. Hobart airport sweltered at 38 degrees. By the end of Wednesday, a sizeable portion of the Frenchman’s Cap National Park resembled a smoking battlefield. Blackened sticks and charred tree trunks stood silhouetted against a background of scorched earth, a scene of utter desolation.

Frenchmans Cap National Park was Australia’s most spectacular mountain park and a place of beauty and wonder for all who visited it. Today, where once the steep mountain sides and ridges were clothed in myrtle and pine, much is now naked mud and ash.208

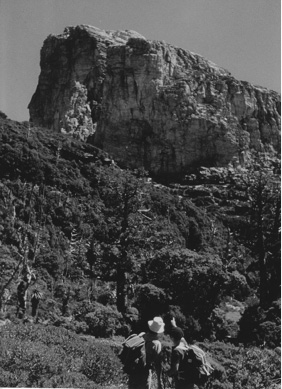

Before the firestorm. The King Billy forest on Tahune Ridge with John Floyd (left) and Jock Gilfillan, February 1964. (Kevin Clarke)

The 1966 bushfire was the greatest natural disaster visited upon Frenchmans Cap in recent times. Half a century later, evidence of the fire’s intensity could still be seen in the fire-scorched cliffs above Lake Tahune, and the blackened slopes of ‘The Thumbs’, a prominent feature overlooking Artichoke Valley.

A rare, high altitude forest of King William pines on Tahune Ridge was destroyed by the fire and has never regenerated. ‘Stags’, the bleached skeletons of large fire-killed trees, stand as stark relics of past fires, rising like ghostly sentinels above the lush green forests of Frenchmans Cap.

Purpose-lit bushfires have been a fact of life at Frenchmans Cap for as long as humans have inhabited Tasmania. Aboriginal people used fire on the button grass plains to flush out game, and to encourage new growth in order to attract grazing marsupials. They used fire sparingly and with great expertise, knowing which time of year would best allow them to control their fires. Usually of low intensity, these fires would finally burn themselves out, or were small enough to be extinguished with branches.209

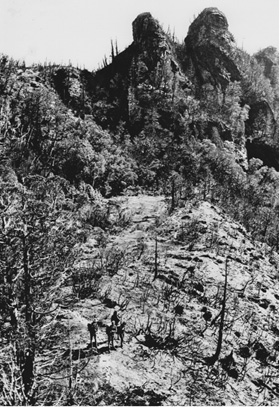

Burnt out Artichoke Valley. (Peter Sims)

Late 19th Century Europeans completely lacked this understanding when they used fire to clear the country ahead. Explorers, track cutters and prospectors lit huge conflagrations, often in hot and windy conditions. For over 50 years, sweeping, high-intensity fires raged uncontrolled across western Tasmania, destroying large tracts of rainforest and inflicting enormous damage. The discovery of minerals in western Tasmania around this time only added to the problem. Random fires frequently escaped from mining towns and quickly swept up into the ranges, wreaking havoc.

The Raglan Range once contained the largest stand of King William pines in Tasmania, a magnificent forest extending from the headwaters of the Governor River to the Eldon Range. Wildfire completely destroyed this forest over the summer of 1897-98, and the King William pines of the Raglan Range have never regenerated.210 In January 1908, big fires were again raging over the west coast and probably burnt close to Frenchmans Cap. In 1934, a fire got away from a work site on the road between Queenstown and Strahan and ended up burning out a quarter of Tasmania.

By the 1930s, bushwalkers were regularly visiting Frenchmans Cap. They returned with firsthand reports of big, uncontrolled fires. Many of these fires were deliberately lit, often by prospectors, and came dangerously close to trapping several bushwalking parties. Views from the summit of Frenchmans Cap were often hazy and the whole region frequently was enveloped in smoke.

Unlike earlier bushfires, the circumstances of the 1966 bushfire are well documented. The bushfire began around 9.30 a.m. on Monday, 21 November 1966. For years it was popularly believed that the fire was started by a party of telephone linesmen boiling a billy over an open fire beside the Lyell Highway. The story ran that a sudden gust of wind caught dry grass nearby and the fire got away from them. In fact, the fire was deliberately lit to clear growth below power lines by a party of three linesmen working in the Nelson Valley, east of Queenstown. When the linesmen drove past later that afternoon, they noticed the fire had spread to a nearby hill. Inexplicably, the men took no further action, and returned to Queenstown without even bothering to report the fire.

Before long, it had swept up into the Raglan Range. By 4.00 p.m. the fire had burnt over the Raglan Range, down the Nelson River Valley and into the headwaters of the Governor River.

Now a wind-driven inferno, it raced across the ranges towards Frenchmans Cap.

The fire was of such intensity that it leaped the Franklin River and other streams. It ‘spotted’ or ‘jumped’ for kilometres ahead, exploding onto high, dry ridge tops. These raging ‘spot’ fires joined up on high places, such as Pine Knob, before moving on to the Cap itself. Lower, wetter areas, such as Vera Gorge, were ‘jumped’ by the fire, thereby escaping the holocaust.

Pine Knob and Artichoke Valley were completely burnt out. The fire also burnt along the foot of the Main Range as far as Sharlands Peak, catching bushes growing 30 m up on the overhanging cliff faces. Providentially, the fire did not burn beyond Barron Pass; instead, as if possessed of a diabolical mind of its own, it crept insidiously around the flanks of Philps Peak, then ‘spotted’ hundreds of metres below onto Rumney Plain, where the dry button grass caught like tinder.

By Tuesday, 22 November 1966, gusty north-westerly winds had carried ash onto the streets of Hobart. Relief arrived late on the third day, when a soaking rain fell overnight. The next day heavy rains finally doused the Frenchmans Cap fires. Four weeks after the fire, a party visited Frenchmans Cap and reported the damage to the Scenery Preservation Board (SPB).

To stand beside the blackened wreckage that was Tahune Hut, to see ash on the surface of the lake and the blackened walls of the amphitheatre rising starkly from its shores, was a depressing scene and one that none in our party will easily forget. The view from the hut site is one of total destruction and it was a sad, silent and angry party that left Tahune and filed back through the charred and dusty landscape to the Barron Pass.211

‘Not a vestige of plant life is left, just the blackened skeletons’. A depressing scene on the way to Barron Pass. (Peter Sims)

There was an immediate public outcry. The bulk of criticism was levelled at the lack of fire protection for Tasmania’s national parks. ‘[It was] Possibly the wildest and most beautiful of our National Parks,’ one letter informed the Minister for Forests, ‘[and] we know that neither we nor our children will see it again in its natural state.’212 Angry letters to the press targeted the Minister for Forests and the SPB for their apathy over the destruction. ‘If fire prevention is to be taken seriously tragedies such as Frenchmans Cap cannot be dismissed ...’ one reader wrote to the Examiner. Another submitted an ‘obituary’ which received wide publicity.

FRENCHMAN’S CAP. November 1966. Result of flagrant negligence by careless people. Loved guardian of Lake Tahune Hut (also deceased). Members of vanishing family of National Parks. Private cremation arranged. Sadly missed by all. Funeral arrangements by Mr Ward, Minister for Forests. Cards, condolences to The Secretary, Scenery Preservation Board. ‘Ashes to ashes, dust to dust. Since man first knew you, your death was a must.’213

Decades earlier, a ribbon of land approximately one kilometre wide on each side of the Lyell Highway had been proclaimed a scenic reserve. This 1939 initiative was due to the foresight of SPB Chairman Colin Pitt. The reserve ran from Derwent Bridge to Gormanston, near Queenstown. It was designed to protect the roadside from the ravages of wood gatherers and deliberately lit fires. The reserve did prevent the wholesale commercial exploitation of timber, but over the years the wider public largely did as they pleased. Reacting to the public outcry after the 1966 fire, a formal investigation was put in train by the district forester and the police in Queenstown.

A police statement was taken from the telephone linesmen, duly signed and witnessed, detailing the full circumstances of the fire. There was plenty of evidence for either the police or forestry to take action. But the matter was simply put to rest. For those enforcing the laws, being a member of the tight-knit Queenstown community could often present a dilemma. These people not only had to enforce the law, they also had to live with and be part of the fabric of town society.

Nevertheless, reluctance on the part of the authorities to act sent altogether the wrong message. Twenty-five years after the 1966 fire, arsonists, firewood gatherers and Huon and King Billy pine poachers were still active in the area. Even today the practice continues, though it is difficult to obtain a prosecution unless the culprit is actually caught in the act. Embarrassingly, many wildfires, both past and present, have originated from ‘authorised’ fires lit by employees of government departments.

A number of people did more than simply complain or write letters to the editor. A party of 17 volunteers spent the Easter of 1967 at Lake Tahune, to take stock of the damage. But even at this early date, some promising signs were emerging from the grim landscape.

Charred tree stumps were springing to life with vibrant green shoots. Large areas of Pineapple grass (Astelia alpina) were sprouting fresh spears. The world-famous mountain shrimp (Anaspides tasmaniae), a survivor of 250 million years of natural catastrophes, could still be seen swimming in Lake Tahune.

However, the fire was of such intensity that it was feared damage to vegetation at the lake would be permanent. Moss had burnt right down to the very water’s edge, and floating ash covered the surface of the lake. Many believed the area would never recover. Peter Sims was instrumental in helping to restore the vegetation to Lake Tahune. Seedlings were collected from similar areas in other parts of Tasmania and planted around the lake.214

Despite some early signs, recovery from the fire was slow. Sixteen months after the event, Brenda Hean noted the affects of the fire.

We passed on now to a scene of utter devastation. The fire had roared up through these valleys and incinerated all before it. Not a vestige of plant life is left, just the black skeletons of once glorious pines and pandani, completely incinerated. There is just nothing left. The track here is hard to find and something must be done soon, as fog, snow or bad weather could be treacherous here in this exposed area.215

Four years later, Brenda Hean would mysteriously disappear in a Tiger Moth aircraft piloted by Max Price, while flying to Canberra to lobby the Federal Government to stop the flooding of Lake Pedder. Rumours and conspiracy theories abounded for decades, but nothing conclusive was ever determined.

In March 1980, Peter Dombrovskis visited Lake Tahune and made his own observation:

There is a sadness in the tree skeletons along the track. This must have been one of the finest high-altitude King Billy pine forests in Tasmania. At the lake, where a few living trees remain to shed seed, there are seedlings. But where all the trees were killed, there is no generation to be seen. Certainly the myrtles, pandannis and mountain leatherwoods and others are regenerating well enough, but without the pines much of the alpine character of the Park has been lost. There may be beauty in twisted trunks, yet how much more beautiful are the living trees! There is beauty in the bones of whales, yet how much more beautiful are the living creatures.216

‘A scene of utter devastation’. A blackened landscape on Tahune Ridge. (Kevin Clarke)

A protégé of Olegas Truchanas, Peter Dombrovskis went on to become Tasmania’s foremost wilderness photographer. His images frequently drew international recognition. His widely-publicised photograph, Morning Mist, Rock Island Bend, Franklin River, Southwest Tasmania, 1979, was instrumental in swaying public opinion in the campaign to save the Franklin River. In 1996, while photographing in the Western Arthur Range, Peter Dombrovskis suffered a fatal heart attack. In 2003, he was inducted into the International Photography Hall of Fame, and in 2010, Peter’s iconic Franklin River photograph was named as one of the top 40 nature photographs of all time.

Earlier wildfires had a similar effect on the pine tree population. Around the shores of Lake Gwendolen and dotting the western slopes of Frenchmans Cap, the stumps of fire-killed King William pines can still be found today. Charles Whitham noticed these dead trees as early as 1914.217 As at Tahune Ridge, these magnificent pines have never recovered from the fierce fires of the past, and the region is the poorer for it.

Since 1966, the declaration of fuel-stove-only areas and wider community education have done much to reduce the frequency of bushfires. The PWS now has available well-trained remote seasonal fire crews. These crews have been successful in eliminating recent fires from the Frenchmans Cap region.

The replanting of genetic stock at Lake Tahune was a caring and far-sighted initiative. Seed was also sprinkled liberally along the high, narrow ledges leading to East Col, directly below the Tahune Face of the Cap. Whether this seed germinated, or nature oversaw the recovery itself is hard to say, but there is now a healthy community of young King William pines taking root on this rocky, elevated terrace on Frenchmans Cap, a new alpine forest in the making.

At Lake Tahune, nature has repaired the damage inflicted upon it in 1966. The purpose-laid seedlings of 1967 that have survived are now much smaller than the surrounding natural regrowth. In its own time, the healing hand of nature has repaired the damage. Artichoke Valley is once more a green and lush oasis. A bushfire has not visited the landscape for many years now, and the Frenchmans Cap region has never looked better. The natural recovery from the last two devastating fires has been remarkable, particularly in the view of the ferocious intensity of these conflagrations. Improved track work has also regulated drainage, creating ideal conditions for the revegetation of King William pines, which seed on average only once every seven years. The vegetation around Lake Tahune, including pines, is growing in abundance unseen for a hundred years.