27 Probing the past

We were young and fit and were just totally in awe of

the place.

During the early 1990s, a scientific research team worked at Frenchmans Cap. A study of Huon pines was carried out in 1993 and 1994 by Brendan M. Buckley, an American graduate student at the University of Tasmania. Core samples were taken from Huon pines in the Frenchmans Cap region to support a study in the science of dendroclimatology, where past climates are reconstructed from the annual growth rings of trees.

Over several days, Brendan Buckley worked with a team comprising six international members. The team worked under the supervision of Dr Edward R. Cook, of Columbia University’s Tree Ring Laboratory in New York. Huon pines were also collected at several sites in Western Tasmania: at Lake Johnston, Harman River, Stanley River and at Frenchmans Cap. Today, the majority of remaining untouched Huon pines are protected in reserves.

At Frenchmans Cap, the team took core samples from living Huon pines at three different locations. The highest site was found along a creek line which drains Artichoke Valley into Livingston Gorge. For ease of identification, the site was named ‘Buckley’s Chance’ and it remains one of the highest known stands of Huon pine. ‘It was one of the more important sites we cored,’ Brendan Buckley recalled.238

At Frenchmans Cap, there exists a perfect niche environment for both King William and Huon pines. Whereas other plant species struggle in conditions of wet and poor quality soil combined with low average temperatures, these magnificent stands of conifers continue to flourish.

Two stands of Huon pine growing at altitudes between 700 and 800 m at Lake Marilyn were also sampled. Brendan Buckley said, ‘The oldest tree from this site germinated before AD 620, with several others extending before AD 1300. Many downed and half-buried logs are found on the forest floor, while several more are detected by probing the deep sediments of the near shore margins of the lake. Lake Marilyn was one of the most wondrous places we went to.’239

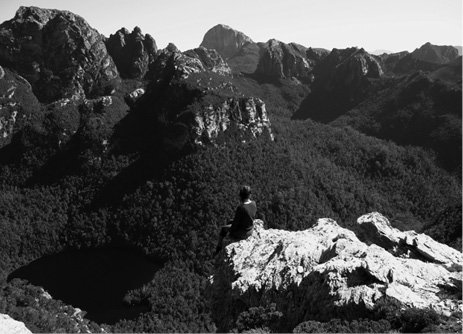

Lake Marilyn. Karen Spinks looks down on Lake Marilyn with Philps Peak rising above and Frenchmans Cap on the skyline. (Karen Spinks)

The last location the team chose was the western shore of Lake Vera.

Vegetation around the lake is highly dependent upon aspect, with Huon pine-dominated, implicate rainforest found along the north-western shore where fire has been largely excluded ... Forty-three subfossil Huon pine logs were recovered from the lake bottom along the western shore in the summer of 1994. These were combined with core samples from 29 living stems from the western shore immediately adjacent to the lake sampling location. The oldest living tree germinated before AD 610, with several more dating back before AD 1000. Subfossil logs extend the chronology back to AD 67, with several logs remaining undated, and likely pre-date the chronology.240

Back in Hobart, the results showed an almost 2,000 year record of tree growth. They also demonstrated that previously unknown fires had occurred at Lake Vera in two periods prior to European settlement. Numerous trees around Lake Vera were killed in about the year AD 1000, and again in the 1480s. Later, Brendan Buckley reflected on his trips to Frenchmans Cap.

I have to say that those days in Tasmania were really my ‘golden days’ in dendrochronology. I don’t think I have ever had as much fun working on anything as I did during that period of time. We scoured the rainforests of Tassie’s south-west looking for trees, but mostly just enjoying the rugged wilderness. We were young and fit and were just totally in awe of the place.241

Another scientific project was carried out at Frenchmans Cap over March and April of 2011. One of the aims of the study, overseen by Michael Fletcher, was to establish the sensitivity of western Tasmania to climate change over the past 2,000 years. For this, information was obtained from pollen core samples taken from sediments at Lakes Vera, Tahune, Gwendolen and Nancy. The study also looked at changes in moisture balance and how abrupt changes in climate affect flora. Another facet of the study looked at how climate changes affect the frequency of bushfires in western Tasmania.

Michael Fletcher reported, ‘A secondary project is a bushfire history project that I am collaborating on that aims to ascertain the baseline fire history of the cool temperate regions of the southern hemisphere over the last 10,000 years, paying particular attention to areas that contain fire sensitive conifer species (Athrotaxis in particular), as these can be used to some extent to reconstruct fire histories from fire scars.’242 The study also collected charcoal core samples taken from sediments from 15 lakes throughout Tasmania, including Lakes Vera, Tahune, Gwendolen and Nancy at Frenchmans Cap. The results will assist future planning for the effects of climate change on water reserves.

In early 2012, Andrés Holz inspected dead standing King William pines and their fire-scar potential for reconstructing fire events in the past 300 to 500 years in conjunction with lake sediment records. Andrés has undertaken extensive research on fire and post-fire recovery with related Gondwana conifer trees in his native Chile. He believes that fires are becoming more frequent and more severe under warming conditions, which in turn might result in less recovery from slow growing King William and Huon pines in the region. Present pollen samples and ancient samples taken from lake sediment provide clues as to which species dominate before and after bushfires. Andrés Holz clarified, ‘This way we can examine whether or not the forest is responding today in a similar fashion to the way it did 1,000 or 10,000 years ago. This should give us an indication of the trends in climate change and of land use changes — from Aboriginal to settler burning.’ Andrés is also seeking an additional permit for work at Lake Magdalen in Livingston Gorge, to ascertain the dates of fires which have scarred or killed lakeside King William pines.243