28 A Future for Frenchmans Cap

It’s a very important area and it shouldn’t be allowed to be damaged in this way...

Repairing the Loddons

By the turn of the millennium, most of the track to Frenchmans Cap had been repaired. However, the main problem — the Loddon Plains — seemed too big a task to complete without a massive injection of government funds. The problem with the Loddon Plains lay with their ‘natural unsoundness’, as James Calder put it in 1840. During periods of high rainfall, both the Franklin and Loddon Rivers swell with huge volumes of water. Often the Loddon River is unable to fully drain into the Franklin. When this happens, its waters back up, overflow its banks and eventually flood the Loddons Plains, leaving them in a waterlogged state for much of the time.

Eventually, the situation on the Loddon Plains had become intolerable. Thousands of bushwalkers’ feet had churned the plains into an extensive quagmire. In many places the track was barely passable. In others, the track had ‘braided’ into a series of minor tracks threading their way through the button grass in a diversionary maze of detours and blind leads that only confused and frustrated bushwalkers. Worse still, the overall impact of all this foot traffic was becoming increasingly destructive to the environment.

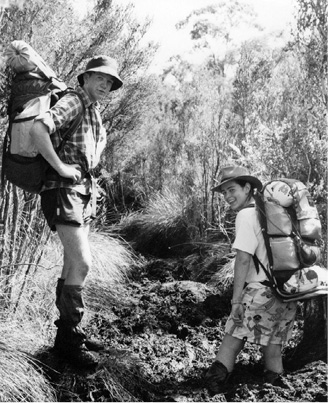

Venturer Scouts, January 1985. Helen Flanagan leads Jennifer Mudge on a wet crossing of Vera Creek. (Terry Reid)

Budget cuts in the first years of the new millennium left the PWS starved of funds. Sometimes even the most basic maintenance work was unable to be undertaken in national parks. The situation was so dire that all track work at Frenchmans Cap stopped. Even during the better times of the 1990s, there was never enough money to carry out the comprehensive repair work necessary to completely ‘harden’ the track and make the ‘Sodden Loddons’ a thing of the past.

In February, 2008, Australian businessman and adventurer Dick Smith made a trip to Frenchmans Cap with his wife, Pip, and friends Robert and Nancy Pallin. The party was repeating journeys to the mountain made in February 1968 and 1988. In the decade following that first trip, Dick Smith established a business empire that made him a household name throughout Australia.

Dick Smith held a lifelong admiration for the Frenchmans Cap region, but in 2008 the state of the Loddon Plains left him dismayed. ‘Whereas some parts of the track have clearly been maintained, there are other parts that are very badly eroded,’ he informed an ABC reporter on his return. ‘It’s a very important area and it shouldn’t be allowed to be damaged in this way … the damage will be almost irreparable if it’s left too long.’244

Knee-deep in mud. Venturer scouts tackle the Loddons in January, 1991. (Terry Reid)

Dick Smith then made a contribution of one million dollars to Wildcare Tasmania, who in turn disbursed funds for the repair and maintainence of the track, as required. Plans were put in place for the repair work to be carried out over a 10 year period. Encouraged by Dick Smith’s offer, the Tasmanian Government also promised to support the project. Dick Smith’s offer of funding came at a time when the track to Frenchmans Cap needed it most.

Repairing the Loddons began in November 2008. Originally, it was decided to relocate the track onto higher and drier ground, hugging the lower slopes of Pickaxe Ridge. But the thin crust of quartzite which gave promise of a solid foundation soon broke away to reveal peat soil beneath. This was soft and quite unstable for forming a base for the new track. It was decided to leave the track where it was, drain it, and use duckboarding (platforms made of wooden slats) where necessary.

The most significant feature of the new work was the replacement of the original Philps Lead Track. Although an important historical link was lost, Philps Lead was always wet and muddy underfoot, and damage to the area was a serious problem. A new route, Laughtons Lead, to be completed in 2013, now leaves the track about 1.5 km before the old turnoff to Philps Lead. This well-constructed track leads mainly through forest and over higher, well-drained ground. It joins the original track where the path climbs steeply through Philps Forest towards Rumney Plain.

It is now possible to walk from the Lyell Highway to the summit of Frenchmans Cap with a sound track underfoot. It is a situation earlier visitors to the region could only dream about. Many returned from Frenchmans muddied from the waist down, vowing never to return until the Loddons were repaired. Now, a good track and wide publicity has led to more and more bushwalkers and trekking companies visiting the region. Their numbers inevitably impact on this fragile area of premier wilderness. This scenario was anticipated, and at the early planning stage, a process was developed by the PWS to accommodate increasing numbers of bushwalkers through improvements to hut sites and regular maintenance programs.

Beyond the duckboarding of the Loddon and Rumney Plains, the button grass moorland requires careful management today. After thousands of years of burning, the flora and fauna of the moorlands has now adapted to fire. Many animals feed on new shoots of vegetation that emerge on the button grass plains after fire. In the present, it is important that we learn lessons from the past — to avoid the destructive bushfires of the white man, and employ the low intensity, controlled burns used so effectively by the Tasmanian native people. This process is also important to ensure a natural build-up of excessive vegetation is not sparked off, most likely nowadays by a lightning strike. Ideally, small burns carried out ‘side by side’ every five years create a mosiac of old and new vegetation through which animals and birds can move freely, thereby invigorating species right through the food chain.

This environmental balancing act is critical when it comes to the forests. If rainforest is seriously burnt, as occurred in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it downgrades to wet eucalyptus forest, then needs at least another 500 fire-free years to revert back to rainforest. High altitude vegetation, such as that seen on the way to Barron Pass and Philps Forest, has no tolerance to fire and should never be burned. The vulnerable interface between these two vegetation types — moorland and forest — is particularly vulnerable, complex and requires careful management. A good example can be found near Lake Vera. Here, the moorlands of Rumney Plain require periodic controlled burns, while the adjacent rainforest of Philps Forest needs complete protection from fire.

Lake Nancy. (Simon Kleinig)

It was no easy matter for Frenchmans Cap to emerge intact into the 21st Century. From colonial times, plans were afoot to open up the country for settlement. Attempts were made to graze sheep on the button grass plains. An endless succession of prospectors and opportunists combed the region in the high expectation of finding gold and other minerals. At one time even a railway was planned to pass close by the mountain on its way through to the west coast.

In Charles Whitham’s time, the quest for progress and the popular notion that man’s dominion over nature was a thing to be encouraged, even admired, were widely regarded as admirable motives. So widespread was this belief in ‘progress’ that Whitham himself was convinced that it would be only a matter of time before roads encroached upon Frenchmans Cap. When this inevitably occurred, Whitham predicted the many names he had given for lakes in the region would be replaced by those of transitory government officials, a trend which had occurred elsewhere in western Tasmania.

Whenever a road is made to the Frenchman, and his secrets are no longer hidden, The Lands Office will blast these highland pools with appellations like Higgins, Watkins, or whoever else may be in the State Ministry at the time.245

Again the rugged terrain surrounding Frenchmans Cap served as a sufficient barrier to discourage development, especially after mineral prospects for the region were discounted. Interestingly, the greatest threat to Charles’s ‘highland pools’ would come much later. The rivers surrounding Frenchmans Cap have protected it from all but the worst invasions of introduced species and bushfires. Ironically, where commercial interests failed to dent Frenchmans Cap’s defences, the very water which coursed and foamed down these rivers in such huge volumes would later present the greatest threat of all to the sanctity of region.

Climate change

It is climate change that could well determine the long term future of the rainforests and vegetation at Frenchmans Cap. Unique Gondawna remnant species, such as Pencil pine, Huon pine, King William pine and Celery-top pine, depend upon icy and frozen periods of weather to germinate. Rainforests need plenty of rain. If global warming continues, new vegetation patterns may emerge at Frenchmans Cap.

Terry Reid says, ‘Climate change is a real issue for relic rainforest in western Tasmania. Global warming will certainly threaten the remaining large, and particularly, small pure rainforest areas. It could be a “death by a thousand cuts”, even without a devastating bushfire. The rainforests may slowly dry out.’

At Frenchmans Cap, the hand of nature continues to sculpt the landscape. It builds, creates and destroys in an endless cycle as it has done for countless millennia. Time changes everything at Frenchmans Cap; not for one second is the future assured.

Today’s society is fully rewarded for each dollar of investment that governments plough into places such as Frenchmans Cap; more so than those governments realise. A trip to the region is not merely a chance to experience magnificent scenery. The mountain provides both playground and therapy for people from all walks of life — from stressed professionals to ordinary people seeking an escape from the hum-drum routine of their daily lives.

In the past, some people felt such a close bond with the mountain that they requested their ashes be scattered from the summit. Marriage proposals have been made and accepted on top of Frenchmans Cap. For many people, over many years, the mountain has served as a popular honeymoon destination. Young people use Frenchmans Cap as a challenge, to learn about themselves, and in so doing, build character. Photographers and artists, writers and poets, all find the mountain an endless source of inspiration.

Barron Pass. Left—Sueann McGuinness, Allen family, Terry Reid, April 2010. (Tristram Miller)

These people immerse themselves in the spirit of Frenchmans Cap. In this manner, the mountain makes a vital contribution to society in a way that is not always appreciated. For governments, this ‘spirit’ represents an intangible, a quality that is impossible to list in state budgets or to equate in terms of return on investment.

In human terms, however, it is the reason people are driven to seek out the wilderness. It attracted the first visitors to Frenchmans Cap, and it continues to do so today. These are primal, sacred and spiritual places and they offer us time for reflection, to unravel, to take stock of our lives. It is here, in the healing surroundings of the natural world, that we are able to spiritually revive and invigorate ourselves.

We all share the finite resources of planet earth. As governments, companies and individuals, we need to take responsibility for what we take from the earth, how our actions affect it, and how we should nurture it. For all our sophisticated posturing, we humans still breathe the same air, share the same planet, and live and die like the rest of nature’s creatures.

For the first half of the 20th Century, wilderness Tasmania was still regarded as a place of terror, a feared wasteland, whose only redeeming feature lay in its ‘taming’ through development. Today, Frenchmans Cap, as part of that same wilderness, is counted amongst the most treasured places on earth.

What would the world be, once bereft

Of wet and wildness? Let them be left,

O let them be left, wildness and wet;

Long live the weeds and the wilderness yet.

Gerard Manley Hopkins (1844–1889), Inversnaid

‘The White Mountain Which Beckons From Afar.’ (Marcus Baker/Getty Images)